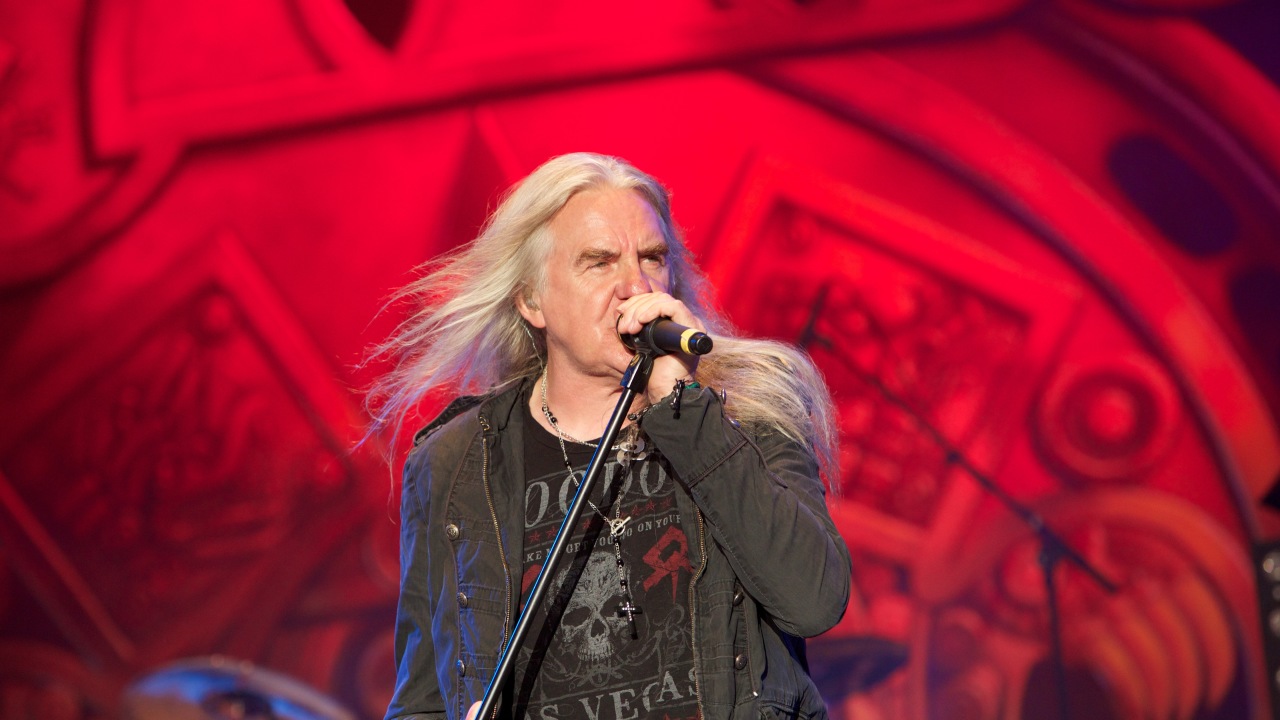

BIFF BYFORD

On a wall of the room hangs a similarly monolithic piece of art. The original painting used for the cover Saxon’s 1984 album Crusader, it portrays a victorious army of holy warriors. And it serves as a reminder not only of the era in which Saxon became one of Britain’s biggest heavy metal bands, but also of the night, eight years ago, when Byford, his wife and four children almost died.

In December 2005, Byford was living in a farmhouse in the French province of Normandy when a fire broke out and set the building ablaze. It was only by luck that he and his family got out alive; Byford had woken suddenly in the early hours of the morning.

“It sounds a bit spooky,” he says, “but I heard a voice in my head. And it was saying: ‘Wake up!’.” To his horror, he saw that the room was filled with smoke. He dragged his wife, Sue, from their bed and ran to their children’s rooms. As he led his family downstairs, flames were pouring through the ceiling above their heads. “It was a close call,” he says. The cause of the fire was never properly identified. It may have been an electrical fault, or a spark from an open fire. The house and most of its contents were destroyed. What didn’t burn was obliterated under a deluge of water from firemen’s hoses. One of the few possessions salvaged from the charred wreckage was the Crusader painting – completely undamaged.

The incident made a deep impression on the family. “It was a huge emotional shock,” Byford says. “You’re traumatised. For years I’d have nightmares and wake up smelling fire. Even now, the kids still go crazy if a smoke alarm goes off. It stays with you. It’s all about that ‘What if?’.”

When Byford first spoke to the other members of Saxon about what had happened, he did something quintessentially British – he made a joke of it. “You know me,” he told bassist ‘Nibbs’ Carter. “I’m a survivor.”

That joke speaks volumes about the kind of man Biff Byford is. On a professional level, it’s an example of his style of leadership, the no-nonsense ethic that has steered Saxon through good times and bad for 35 years. On a personal level, it’s less a joke and more a reflection of the hardships that Byford has experienced in his life from an early age. The lines in his face have been well earned.

Biff performs Motorcycle Man with Metallica in 2011 in San Francisco

Born in Honley, West Yorkshire, on January 15, 1951, he was just 11 years old when his mother died. “Being so young,” he says, “it was a crushing blow. But that, I think, is when that will to survive was built in.”

Only two years later his father suffered a terrible accident while at work at a textile mill, losing an arm after it was entangled in a piece of heavy machinery. Byford’s elder siblings – a brother, a half-sister and half-brother – had already left home. But, with the help of relatives, he managed to care for his father. “I had to grow up very quickly,” he says.

When he was 15, having left school to work as a junior carpenter, his world was again turned upside-down when his first steady girlfriend, Linda, fell pregnant. They were promptly married. “It’s what you had to do back then,” he says, matter-of-factly. But the marriage didn’t last, even though the couple had two children. Byford didn’t want to be tied down. He had dreams of being a rock star.

Music had provided a form of escapism for Byford during a difficult childhood. He joined a youth club band at 14, and began to overcome the shyness that had troubled him for years. “On stage,” he says, “you’re acting.”

Most important of all, music would offer a route out of the coal mines and factories in which Byford, like so many of his peers, seemed destined to spend his entire working life.

At 18 he was employed at the Shuttleye pit at Flockton, near Huddersfield. At six-foot-one he was considered too tall to work underground, in tunnels only three feet high. So instead he worked in the boiler house, manning a giant steam engine that drew up the coal from a mile deep. And every day he dreamed of a better life away from the coal mine.

He was taught to play guitar by his best friend’s brother, who led a local blues group. Byford switched to bass, and passed through various bands in the Barnsley area. He started singing backing vocals when he joined the Iron Mad Wilkinson Band, named after a local industrialist. Then, in power-trio Coast, he graduated to lead singer. In 1976 he and Coast’s guitarist, Paul Quinn, joined up with Graham Oliver and Steve Dawson, both members of rival band SOB. The new band was renamed Son Of A Bitch. When the band signed to Carrere Records in 1979, they were rechristened Saxon. Saxon has been the focus of Peter ‘Biff’ Byford’s life ever since.

Success for Saxon came quickly, in the early 80s, via three classic albums: Wheels Of Steel, Strong Arm Of The Law and Denim And Leather. A steep decline followed at the end of that decade, when the band watered down their music in a futile attempt to break the US market. A comeback was achieved in the 90s when, as Byford says: “I made the decision to make the music heavier again.”

Saxon is, and always has been, Biff Byford’s band. Through all the ups and downs in their lengthy career, only Paul Quinn has remained at Byford’s side, although drummer Nigel Glockler has been in the band since 1981. Byford managed the band’s business affairs for 10 years. And he now owns the trademark for the Saxon name, following a court victory over sacked ex-members Oliver and Dawson.

“In every band,” Byford says, “there has to be a leader. Somebody has to make decisions. And that somebody is me.”

Saxon’s longevity is a testament to his tenacity – the ‘will to survive’ that became a fundamental part of his psyche in the wake of his mother’s death.

Byford is not a rock’n’roll survivor in the clichéd sense of a recovered alcoholic or drug addict. He is now a social drinker, but for the whole of the 80s, when Saxon were at their peak, he never touched booze – he didn’t want to end up like his father.

“My dad was basically an alcoholic,” he explains. “He’d come home drunk and hit you with his belt. It was quite brutal.”

He nevertheless remained loyal to his father. “He got nicer as he got older.”

And in recent years, Byford has been in contact with his two children from his former marriage.

“It’s not like we’re running into each other’s arms,” he explains. “We’re just talking, really. It’s difficult when you have another family.”

Looking back, Byford insists he has no regrets on that score. “I moved on to a different life,” he says. “How could I regret it? I did what I felt I had to do.”

There’s a hardness in those words. But for Biff Byford, it was the hard times in his life, at such an early age, that did most to shape him.

“It’s when I think about the night our house burned down, when we nearly died – that’s when you realise how precious life really is.”

TIM ‘NIBBS’ CARTER

Tim ‘Nibbs’ Carter is a big personality, both on stage and off. Put him in front of an audience and he’s a live wire, constantly mugging to the crowd or windmilling his head. When socialising he’s a raconteur of near-limitless capacity. But it’s in the quieter moments, when he talks about what matters to him most in his life, that he reveals himself as a deeply troubled man.

Strong Arm Of The Law live with bass solo!

At 46, Carter is still slim, his long hair still thick. It’s only the lines in his face that give away his age.

It’s a grey February afternoon, and he’s sitting in a corner of the Ingram Arms in Doncaster, starting his fourth pint of lager. He’s a long way from his home in Germany. And home is where he now spends almost all of his time, caring for a wife who is seriously ill, and looking after their four children. For Carter, there are no other priorities.

It was in 2010 that his wife, Tina, was diagnosed with sarcoidosis, a disease that affects the nervous system, similar to multiple sclerosis. Three years on, she’s now confined to the family home in Ankum, a small German town close to Osnabruck. Tina’s treatment is organised through the national health system. “There are three levels of care,” Carter explains. “Level 3 is where you don’t get out of bed any more and you need someone to carry you and bathe you. Tina is now on Level 2.”

He does his best to accentuate the positives. “Tina has to use a wheelchair, so we’re trying to get a lift to take her upstairs. And her mother has moved to where we live so she can be with her.”

It’s when Carter reflects on the effects of her medication that his emotions show in his voice and on his face. “She’s on opiate medicine,” he says. “Morphine drops. She sleeps for 16 hours a day. She’s such a beautiful woman, but so fragile…”

But something stops him. After a brief pause, he smiles and his voice lifts. “If Tina was here right now,” he says, “she’d tell me: ‘I think you’ve had enough now’. And I’d be like: ‘Fucking hell, I’m with Classic Rock!’. And she’d be like: ‘Oh, alright then’. She might even have a Southern Comfort herself. She’s German – and they can drink.”

When Carter looks back and takes stock of his life, he says it was second nature for him to raise a large family. He was the youngest of six children, born on September 6, 1966, in the Lincolnshire seaside resort of Cleethorpes. His parents ran a fruit and veg stall in nearby Grimsby. His father succumbed to cancer when Tim was nine.

“I came home from school one day and my auntie Beryl was waiting for me,” he recalls. “She said: ‘Your dad’s died. You can go upstairs and have a cry’. That’s not something you forget.”

He has happier memories of a family home filled with music. His mother, now 85, used to sing in pubs in Grimsby, and his siblings were always playing records: 70s rock and disco. In his teens Tim learned to play bass. At 18 he joined his first serious band, backing Bram Tchaikovsky, former guitarist with punk-era pop-rock band The Motors. It was Tchaikovsky who named him ‘Nibbs’, for no reason other than it sounded amusing.

Carter was 22 when he got the job with Saxon in 1988. The band’s career was in decline. “I knew they weren’t the dog’s bollocks any more,” he says. But, as a Saxon fan since childhood, he was thrilled to be joining the band. It was on a Saxon tour in 91 that he met Tina. A student in sound engineering, she was working on the stage monitors on the band’s German dates. was the only girl on the crew, so everybody was trying to chat her up. But by the end of the tour we realised we liked each other.”

They were married in 1994, when Tina was pregnant with their first child, Charlotte. Over the next 10 years, as their family expanded, they lived in Hull, then Germany, and then Grimsby, before finally settling in Ankum in 2004. For six years, Carter found it easy to balance his life in Germany with his professional commitments: recording Saxon albums in the UK and touring throughout the world. But since Tina fell ill, he has struggled with that balance.

In 2010 he was given compassionate leave from Saxon’s European tour. Danish bassist Yenz Leonhardt stood in, although an official statement described Carter as “irreplaceable”. For Carter, and for Saxon, the situation remains difficult. During the writing of their new album, Sacrifice, he stayed at home and worked on songs using his laptop. But recording the album, done near Wakefield, took him away from home for long periods of time. And touring, he says, is “a nightmare”.

He admits that he wouldn’t normally speak about these things to anyone other than his family and close friends. He even says, unexpectedly: “Thanks for listening to that stuff.” But this is the reality of his life. These are hard times, and he is simply doing the best that he can – for his wife, for his kids and for the band.

“I’m lucky to be in a band like this,” he says. “I’m pretty weak when it comes to booze, and I’m thankful that there are responsible characters around me.”

He looks down at his pint glass, now empty, and thinks long and hard. “If I didn’t have these guys with me, I might be getting wasted every night. And maybe I wouldn’t be here now.”

DOUG SCARRATT

Doug Scarratt had never been in a heavy metal band before he joined Saxon. In fact in his previous job he’d been playing soft rock with Baywatch star David Hasselhoff.

In 1995, when Saxon were looking for a new guitarist following the sacking of Graham Oliver, their drummer, Nigel Glockler, suggested that his friend Scarratt was a perfect fit. And Glockler was right. As he sits in the Hove flat he shares with his wife Jane and their 12-year-old daughter, he admits that at first he found it difficult to assimilate into the band.

“I jumped straight into a tour, and had to figure out who these guys were,” he says. “But when the tour was done, and we started writing songs together, that’s when, finally, I felt like a band member.”

Stand Up And Fight with guitar solo

Now 53, Scarratt spent his first 10 years as a pro musician playing Top 40 covers, gigging with blues rock groups and doing “anything that would pay me a wage”.

Now he’s part of one of the all-time great metal bands. And, most important of all for Scarratt, it’s a band that’s still moving forward. “As a musician,” he says, “your creativity is everything.”

After 18 years in Saxon, Scarratt has just one complaint. “I hate touring. The gigs are great, but being away from home for months, living on a tour bus with a bunch of blokes… for me, that’s purgatory.”

NIGEL GLOCKLER

In his house, Saxon drummer Nigel Glockler has a small room fitted out as a home studio, where he and his near-neighbour, guitarist Doug Scarratt, work on Saxon songs, and also make their own music – instrumental pieces, some of which have been used in TV shows such as Spooks. “Some days,” Glockler says, “I wake up and I’m Vangelis.”

One of two southerners in a quintessentially northern band, Glockler was born and raised here in Hove. He’s owned this house since 1985, and in his lounge are mementoes of his long career in Saxon: by the fireplace is an old bass drum serving as an occasional table; on a wall covered with framed photographs, there’s a band publicity shot from the mid-80s, in which a fuzzy-haired Glockler is sporting that classic 80s rock star fashion accessory: the headband. What’s more, he claims this was a look that he pioneered.

In February 1981, eight months before he joined Saxon, Glockler wore a headband on Top Of The Pops while performing with new-wave star Toyah. When he watched the show the following week, he was astonished. “All of Duran Duran had bloody headbands on!” he says. “But I was the first. I was quite a trendsetter.”

That comment is typical of a man who rarely misses an opportunity for a funny one-liner. Pointing to one of his two cats, a furry ginger tom that could double as a rug, he says fondly: “That’s Phil – as in Mogg.” And when his wife, a Texan called Gina, arrives with tea and home-baked cupcakes, he complains that she’s banned him from playing his favourite music, 70s prog rock, in the house. “If I want to hear some Van der Graaf Generator,” he says, “I have to do it in the car.”

He’s more serious, however, when talking about Saxon, and his role as the band’s “engine room”.

At 60 (a landmark he celebrated with Iron Maiden’s Nicko McBrain at a music convention in California) Glockler is both proud and a little surprised to still be a rock drummer at his age. And having dedicated 27 of those years – from 1981 to 1999, and from 2005 to the present – to Saxon, he remains fully committed to the band.

“None of us really knows how long we’ll go on,” he admits. “But this is still a bloody good band.” He smiles, and adds: “If it wasn’t such a good band, I wouldn’t still be in it.”

PAUL QUINN

There’s a scene in the Saxon documentary Heavy Metal Thunder: The Movie where Motörhead mainman Lemmy is recalling the first tour that the two bands did together, in 1979. He describes each member of Saxon’s classic line-up succinctly: singer Biff Byford was “a show-off”, bassist Steve ‘Dobby’ Dawson “the nutter”, guitarist Graham Oliver “the musical one”, drummer Pete Gill simply “odd”. But the one guy that Lemmy just couldn’t figure out was Saxon’s other guitarist, Paul Quinn. “Really quiet,” Lemmy says. “I never said 10 words to him on the whole tour.”

Thirty-four years on, Paul Quinn might look very different – heavier set, and with his head now close-shaven – but he remains an introvert: the quiet man of Saxon. Speaking to Classic Rock at a place he knows well, instrument shop Electro-Music in Doncaster, he is at first defensive.

“I’m not that interested in telling the world what makes me tick,” he says flatly. “There’s a Yorkshire expression: I know my own know.” But, over the course of an hour, he opens up more and more.

Quinn was born on Boxing Day, 1951, in Maltby, a small Yorkshire town near Rotherham. He describes his upbringing as “typically working class”. His father worked in the mining industry, albeit in a white-collar role as a safety planner. In his teens, Quinn secured a good job as a recording technician in a school language lab. “That would serve me well later on,” he says.

The turning point in his life came in his early 20s, when he started earning good money gigging on weekends as a member of covers band Pagan Chorus, playing rock and “cabaret-style” pop. Eventually he quit his day job to become a professional musician. One night in the mid-70s, after a Pagan Chorus show at Barnsley nightclub Baba’s, Biff Byford pulled him aside and told him: “You’re too good for this.”

Quinn and Byford formed a new band, Coast, to play authentic rock music, minus the cabaret stuff. And they’ve stuck together ever since. When Byford was invited to join another local band, SOB, he insisted that he and Quinn came as a package deal. From this, Saxon was born. And throughout the band’s 35-year career, Quinn has stayed loyal to Byford as the singer’s trusted lieutenant. Their relationship is, however, a little unusual. “We’re both Capricorns, so we know how to relate to each other. Capricorns are faithful – which we’ve proved. But we keep a distance. We’re not overly lovey. People have to grab me for a hug. And I wouldn’t dare grab Biff for a hug.”

Byford, meanwhile, claims that they are “like brothers”. But he also admits that he finds Quinn a difficult man to read, even after all these years. “You have to look after Paul,” he says. “He’s quite high-maintenance. And sometimes he’s just on a different planet. Like the time we did a radio interview together and he just nodded all the way through. He’s a bit like Spike Milligan, his sense of humour is so wacky.”

Quinn is indeed a funny man. He describes Byford’s leadership of Saxon as a “mockracy”. And when asked about the wig he wore in the 80s and 90s, he says: “Our manager felt that the band needed its own King Charles.” But he prefers to think of himself as reserved rather than eccentric. “I’m pretty normal,” he shrugs. “When I go on stage I turn into Mr Hyde, but that’s what most musicians do.”

And the life he has now, as he describes it, seems as normal as is possible for a 61-year-old heavy metal guitarist. When he’s not working, Quinn divides his time between his home in Barnsley and his Dutch girlfriend’s home in The Hague. He has a 19-year-old daughter living Hanover, Germany. Her mother, Quinn’s ex-wife, died in April 2012. Quinn speaks to his daughter regularly via Skype. And although he feels sad that he missed parts of her childhood by being absent on tour, he tries not to linger on the bad stuff.

“Humans have a tendency to blame themselves for a lot of things,” he says. “But I was the breadwinner. It was a difficult juggling act. And I try not to beat myself up about it. The fact that I try to be a good human being is probably enough. I’m not religious, but that’s what I believe in.”

Paul Quinn might have his idiosyncrasies, but the quiet man of Saxon might just be the wisest.

This was published in Classic Rock issue 183.

Read a Q&A with Biff here.

Where can you next see Saxon live in the UK? Their 2014 tour dates are here.