As co-founder of the design team Hipgnosis, who became synonymous with Pink Floyd’s best-known album art, Aubrey ‘Po’ Powell’s photography has played a significant role as a visual companion to prog, adorning the covers of some of the genre’s biggest albums from Yes and Genesis to The Moody Blues and Peter Gabriel. In 2023, on the 50th anniversary of The Dark Side Of The Moon and with Hipgnosis’ iconic design back under the spotlight, Powell revealed the secrets behind the team’s most famous work – and his plans to keep Hipgnosis and Floyd’s flame burning.

Aubrey ‘Po’ Powell walked out of his first job with Pink Floyd in April 1967. He’d driven their lighting rig from the Netherlands to London’s Alexandra Palace, where Floyd were headlining The 14-Hour Technicolor Dream. “I think we’d all been up for 36 hours,” he recalls. “Everyone was exhausted.”

Pink Floyd were due onstage at dawn, and Roger Waters asked Po to fetch him a bottle of whisky. He reminded him that he wasn’t a gofer. “But Roger said, ‘Fucking go and find me a bottle of whisky.’ At which point I said, ‘Goodbye’, got in my van and left.”

Fifty-six years later, Powell is employed as Pink Floyd’s creative director, a role he inherited after the death of his old friend, Storm Thorgerson. Throughout the 70s, he and Storm were the leading lights in Hipgnosis, the art house behind some of the world’s most famous album sleeves, for Pink Floyd, Yes, Genesis, 10cc, Peter Gabriel, Led Zeppelin and Paul McCartney.

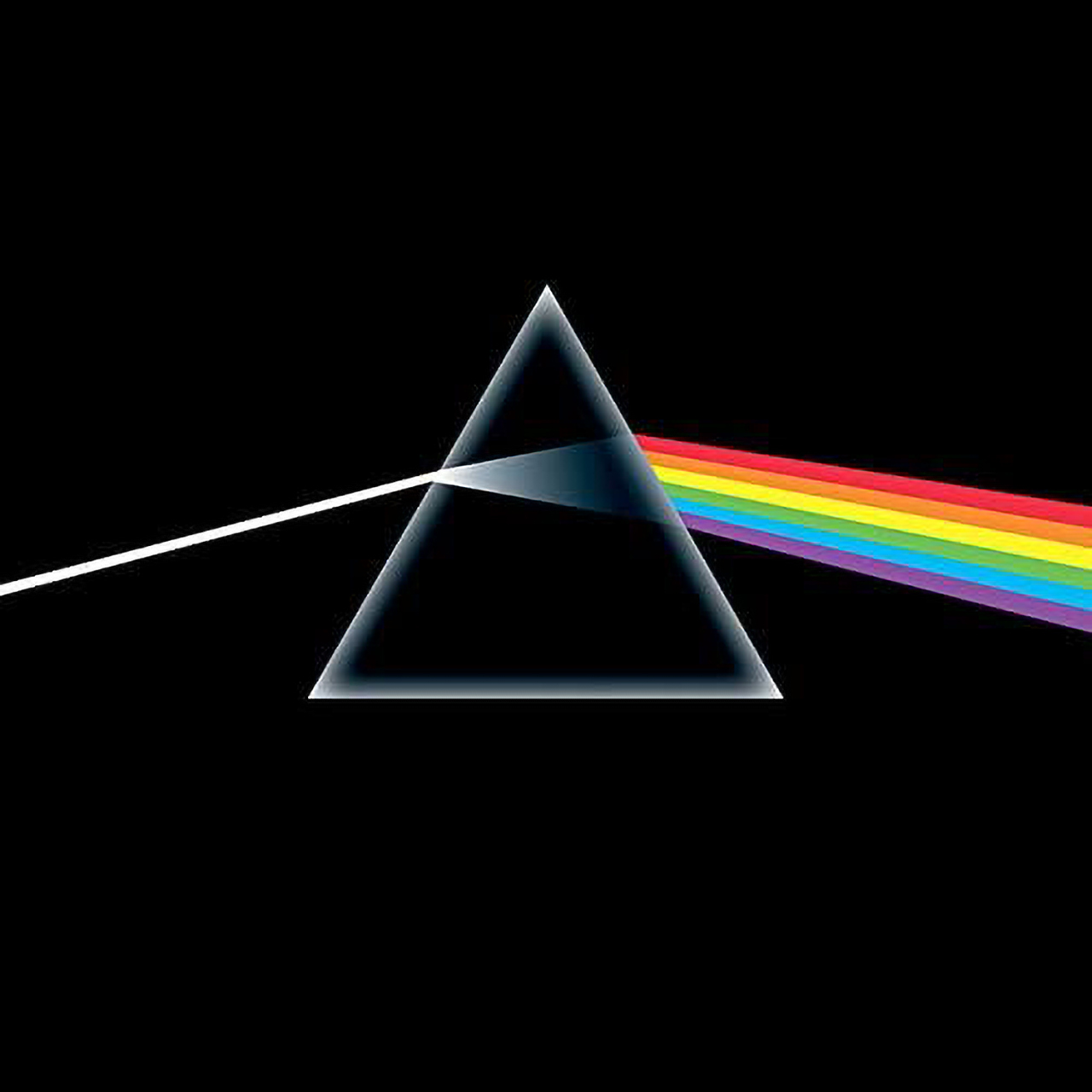

Interest in the Hipgnosis story has reached an all-time high. Their best- known artwork, The Dark Side Of The Moon, has just turned 50; their wild adventures are recounted in a new biography, Us And Them (“A rollercoaster of a book,” he says); their greatest hits are being exhibited in Netherlands’ Groninger Museum, and filmmaker Anton Corbijn’s Hipgnosis documentary, Squaring The Circle, is due for theatrical release later this year.

“There’s definitely something in the air,” says Powell, now 76 years young. “People are still fascinated, and I’m working harder than ever. I just wish Storm was here to see it.”

What surprises do Pink Floyd have planned for the 50th anniversary of The Dark Side Of The Moon?

The collective view is that the whole year will be a celebration. We’re still deciding when, but there will be playbacks of the album at planetariums around the world. I’ve been working with a wonderful team in Leicester, who have created films for each track. Some are psychedelic, some are narratives, some are like Kubrick’s 2001, and some will have you zooming down the canyons of Mars and nearly puking out of your seat.

Did you attend the original Dark Side playback at the London Planetarium?

I did; I remember walking in and seeing cardboard cut-outs of the band. They refused to attend – they didn’t think the sound system was good enough. Rick Wright turned up for five minutes, not realising the others had snubbed it. Communication was never their strong point, even back then.

We all gossip about each other, but I never take sides. That’s a position I’ve always maintained

Can you tell us anything about Roger Waters’ new version of the album?

It was supposed to have been performed publicly in February but has been put off. As I understand it, there may be new lyrics and it may be more in the context of spoken word, with less emphasis on guitar solos and the like. Which is interesting, as Roger released a statement recently praising his nemesis David Gilmour’s guitar skills, saying, “I love Dave’s guitar solos on The Dark Side Of The Moon, both of them.” However, not having had the pleasure of hearing it I can comment no further.

What’s the secret to surviving as Pink Floyd’s creative director?

It helps that we’ve known each other for over 50 years. We’re friends, so it doesn’t matter if we’ve not seen each other for ages; as soon as we walk in a room together – bang! We’re joined at the hip. We all have the same memories: growing up in Cambridge, the UFO club, Storm Thorgerson...

Is it difficult to stay impartial?

We all gossip about each other, but I never take sides. That’s a position I’ve always maintained. I have been around too long to be afraid of anybody, so I always say what I think, and if somebody doesn’t like it, it’s okay, just move on.

How did you first meet Storm?

Through a mutual friend, our dope dealer. I’d been kicked out of boarding school in Ely at 16 [in 1963], and was lodging at a house in Cambridge, around the corner from Storm’s place. Storm had been to the same school as Roger Waters and Syd Barrett, and also knew David Gilmour. I was introduced to this group of extraordinary individuals – would-be painters and writers and musicians.

Did you have a lot in common?

Yes. His parents were divorced and he lived alone with his mother. My parents were overseas, as my father was in the RAF. Neither of us had siblings, and we both read the same books – Kerouac, Ginsberg – and listened to Bob Dylan. It was intimidating, though, because Storm was smart beyond belief and I had to keep up.

How did Hipgnosis come about?

Storm and I moved to London in 1966. Storm went to the Royal College Of Art and I designed sets for the BBC, and drove Pink Floyd’s lighting rig in my minivan. Then I got into trouble with the law. Some friends and I were charged with credit card fraud, and nearly went to prison. This was September 1967 and it was a turning point. I realised I didn’t want to waste my life. Storm had shown me how to take pictures and I knew I wanted to become a photographer. That was the beginning.

There was a communal toilet on the landing but that was so bad we often used the darkroom sink

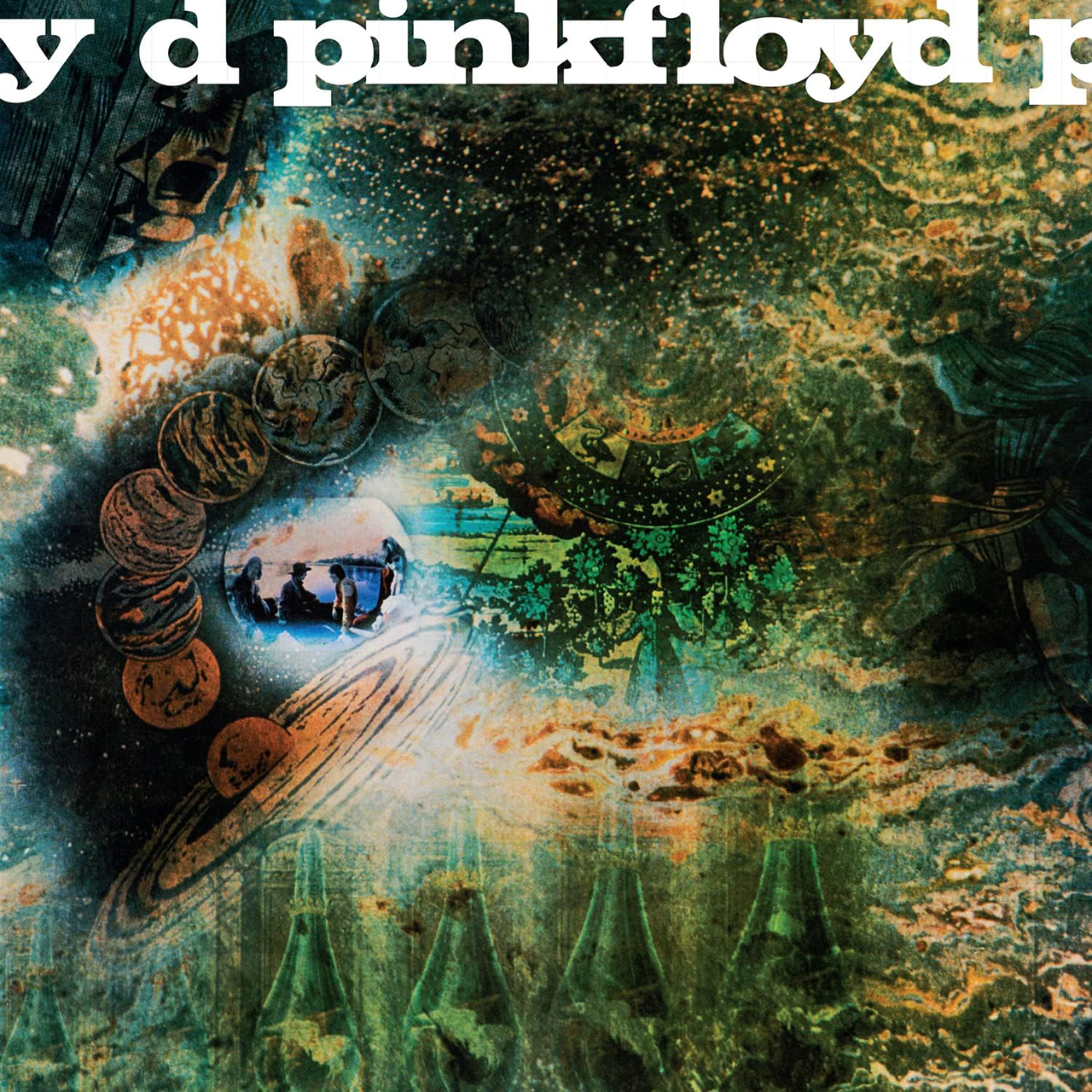

Pink Floyd’s A Saucerful Of Secrets was Hipgnosis’ first record sleeve in June 1968. How did that come about?

Storm asked the band if we could design the sleeve. We’d been impressed by Peter Blake’s artwork for Sgt Pepper. It was a piece of living sculpture – radical! Pink Floyd wanted something different, too, so we created a collage out of Marvel comics and zodiacal charts, and developed it in the RCA darkroom. But I remember delivering it to the head of EMI’s art department – me in velvet trousers and beads, saying, “Hey, man, here’s the Floyd cover” – and he looked at me like I didn’t exist. It was the moment Storm and I realised we would never work for the record companies.

Nick Mason says Pink Floyd were usually happy to back Hipgnosis up. Is that true?

Yes. Storm hated the record companies and they hated him. Storm’s attitude was: “The art comes first, the money comes second.” He was right – though he was also terrible with money. We charged £150 to £200 a cover when we started, until we decided to ask band managers what they were willing to pay. The Sweet’s manager suggested £800 – and we rubbed our hands with glee.

Where did the inspiration for Hipgnosis’ ideas come from?

Often Storm’s imagination. Storm used to dream ideas, which he called “plundering the goldmine.” But also books, drugs, photographs, paintings, movies... We’d have weekly brainstorming sessions lasting most of the night. Everyone was encouraged to attend: designers, photographers, Japanese groupies, knife-throwing drug dealers...

Storm and you had different roles at Hipgnosis beyond him dreaming up the ideas and you taking the photographs, though.

Yes, Storm was quite feral, because of his upbringing. He’d spent his early years at Summerhill [a progressive school in Suffolk, where lessons were voluntary]. It made him unafraid, but also uncompromising. One of my jobs was smoothing things over with people like Paul McCartney. Paul and Storm did not get along. Paul thought he was rude.

Hipgnosis’ studio at 6 Denmark Street made a big impression on many visitors. Wishbone Ash’s Andy Powell told us it was “disgusting.”

Andy is quite right. There was a communal toilet on the landing but that was so bad we often used the darkroom sink. Some advertising agency execs once visited to talk about a campaign for Mercedes. But they told us they could never bring their clients to a place like this, so we showed them the door.

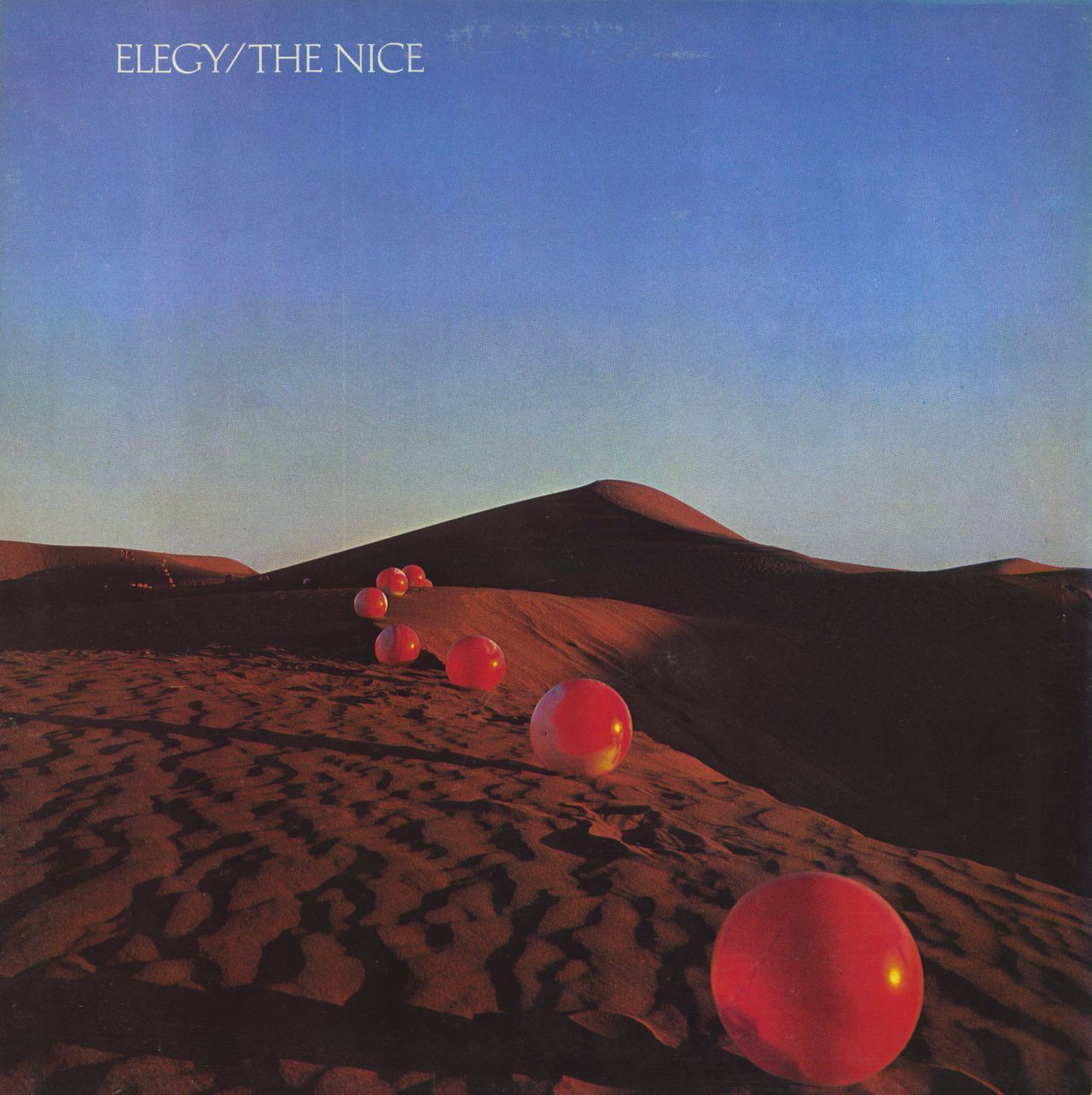

Pink Floyd, Quatermass, Argent, The Nice... Hipgnosis illustrated that first wave of progressive groups. Any favourite covers?

The Nice’s Elegy is still one of my favourites. It was the first time we’d done a cover shoot overseas. Tony Stratton-Smith, the head of Charisma Records, paid for us to go to Morocco and shoot a load of footballs in the Sahara. That cover made Storm and I realise we could create a piece of land art totally unrelated to the name of a band or the name of their album – and Keith Emerson loved it. Hipgnosis’ policy was always: “Think sideways.” Much more exciting than just taking photos of a band.

We did some bad covers for Renaissance. We didn’t mean to… we learned from the bad covers

Are there any of those early sleeves you don’t like?

Of course. We did some bad covers for Renaissance. We didn’t mean to. Sometimes we had to do things cheaply because a band didn’t have much money. But we learned from the bad covers.

Yet the cow on the sleeve of Floyd’s Atom Heart Mother cost nothing and is still talked about today.

Yes, that was inspired by [French painter] Marcel Duchamp, who took everyday objects and turned them into a piece of art. How much more everyday could you get than a cow? But at the time I thought it might be a step too far. I was more pragmatic than Storm and didn’t think so laterally. Of course, I was wrong.

It seems like 1973 was a turning point: The Dark Side Of The Moon, Led Zeppelin’s Houses Of The Holy, Paul McCartney’s Band On The Run...

Everything took off that year. But The Dark Side Of The Moon wasn’t a typical Hipgnosis cover. Rick Wright asked us if we could design something that looked like a Black Magic box of chocolates, which Storm was rather cross about at the time. So we found this design in a physics textbook. But that cover changed everything. We became the go-to record sleeve guys.

Did you notice a change in Pink Floyd after they had such a big hit album?

Yes. It happens to any band in that situation: you become rich and don’t always know how to deal with it. Suddenly you realise you don’t have to share a room in a Holiday Inn with a guy whose socks smell! You can have your own room, your own limo, your own Learjet – “Keep your hands off of my stack” – and that did happen.

Did your relationship with Storm change at this time?

Yes. Storm was a single father and had to look after his son. He didn’t go away on shoots. So I took most of the photographs; but if you’re in the Mojave Desert, you have to think on your feet. We didn’t have mobile phones to check in with the office. It empowered me, but also meant we argued more. I loved Storm like a brother, but we also fought like brothers.

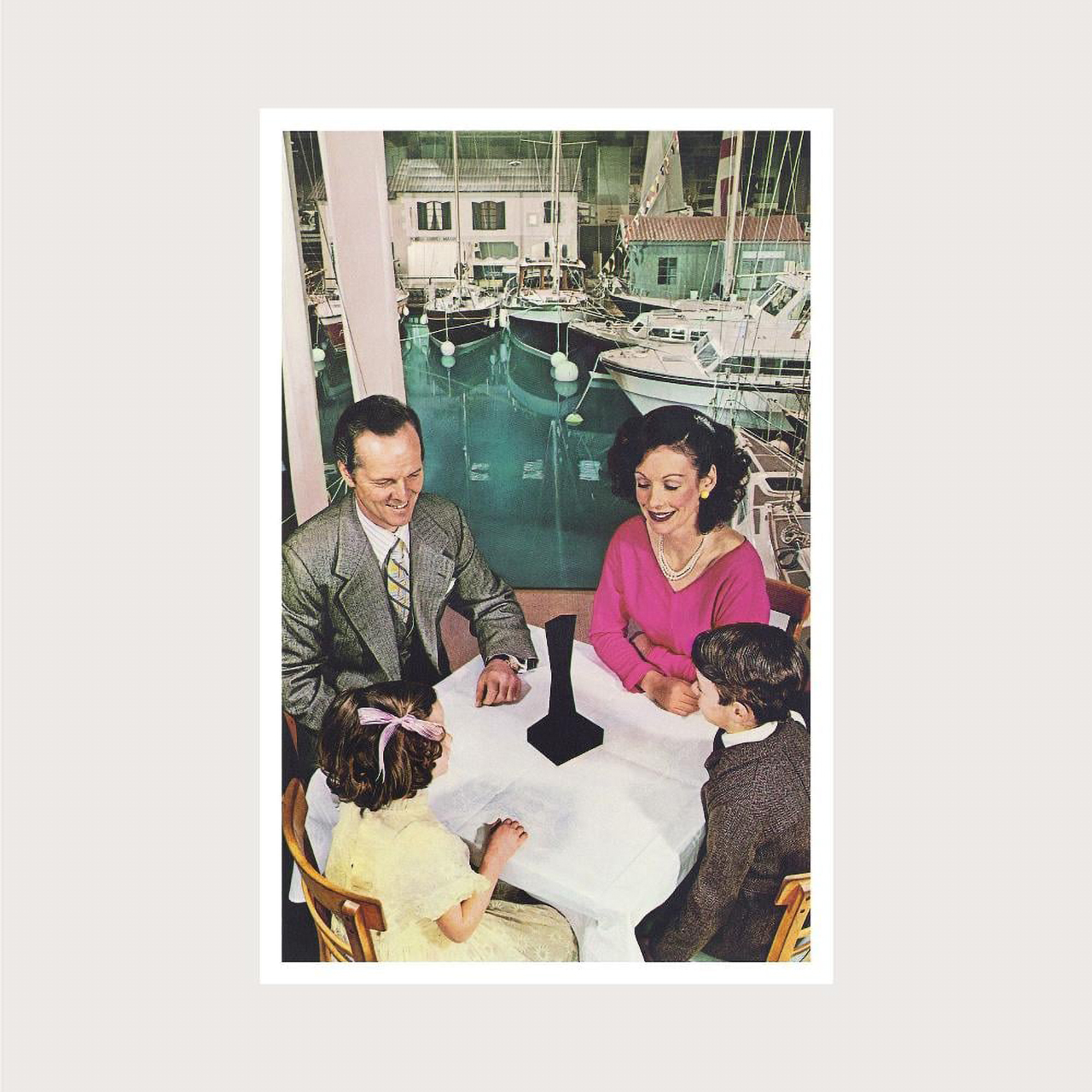

That run of Floyd albums – Dark Side, Wish You Were Here, Animals – includes some of Hipgnosis’ greatest hits. What was behind that drive?

I’d include Led Zeppelin’s Presence as well. I take my hat off to Jimmy Page that they allowed us to do it. That black object had fuck-all to do with heavy rock. It was a real piece of art. Zeppelin and Floyd trusted us to come up with the goods. We had complete freedom, and money was no object.

Roger went with Gerald Scarfe for The Wall. I’m not sure Storm ever forgave him

Wish You Were Here seems like an incredible production.

Yes, we had four cover images in one package. We spent two months in LA, scouting locations, setting a stuntman on fire, shooting an upside-down diver in Mono Lake, photographing a male model in the Glamis sand dunes... and then Storm covered the whole package in black shrink wrap. It was brilliant.

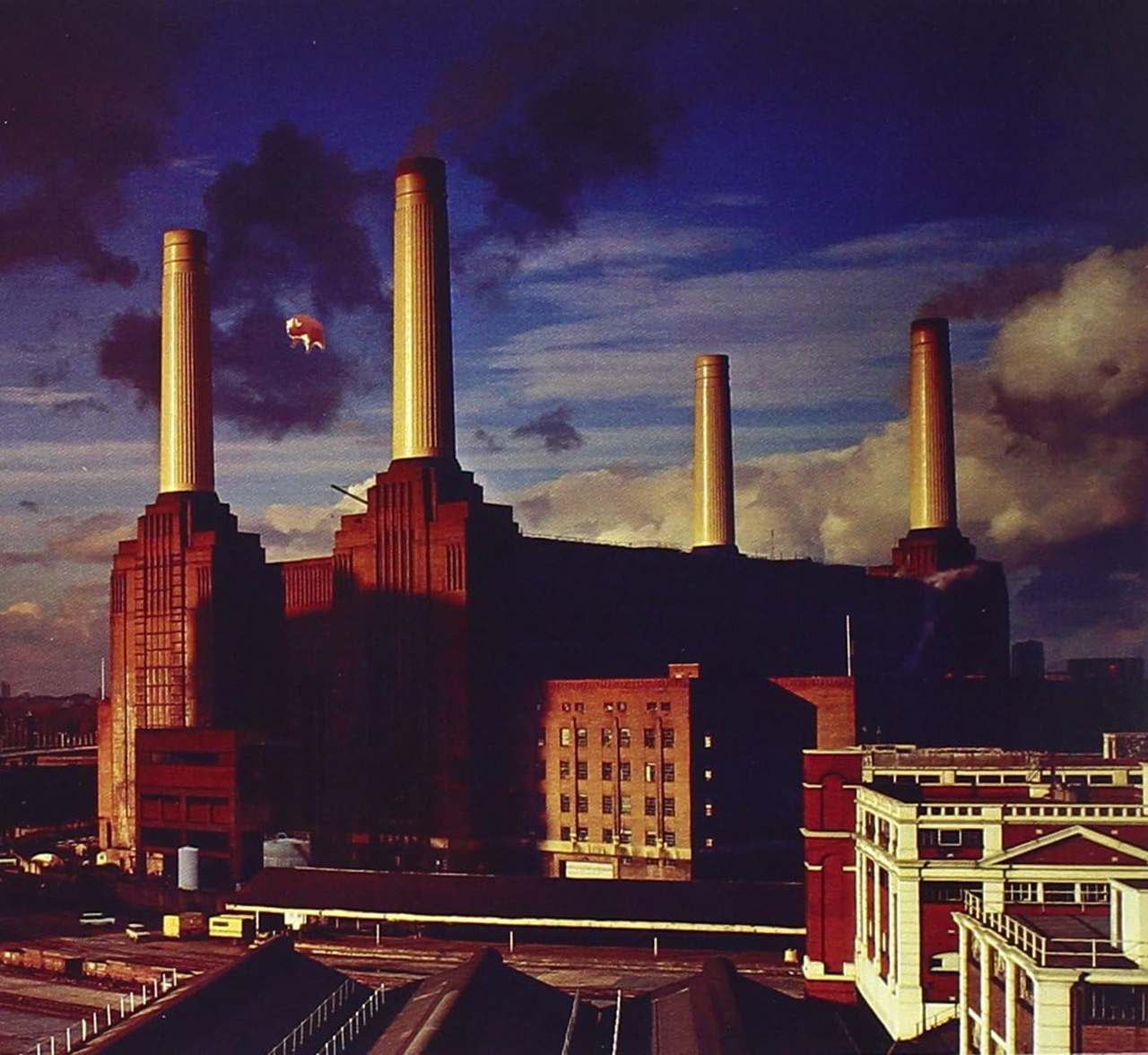

Many people presumed the inflatable pig escaping during the Animals shoot at Battersea Power Station was a publicity stunt. Was it?

They did, and we couldn’t have hoped for better publicity. But it wasn’t intentional. It was terrifying because it could have caused an air accident. I was on Battersea Bridge when the pig broke free. I drove down to the power station where the band were watching, and saw this look of schoolboy glee on Roger Waters’ face. All of them couldn’t wait to jump in their Range Rovers and piss off – “You sort this out, Po.”

Why didn’t Hipgnosis design The Wall?

We published a book of artwork called Walk Away René [in 1978] and Storm didn’t mention that the pig on the cover of Animals was Roger’s idea – and Roger was very angry about that. Storm and Roger hadn’t been getting on anyway. The band had rejected Storm’s earlier ideas for the album, one of which was a drawing of a small boy opening his parents’ bedroom door and finding them fucking. Roger thought that was inappropriate. But after Walk Away René, Roger went with Gerald Scarfe for The Wall. I’m not sure Storm ever forgave him.

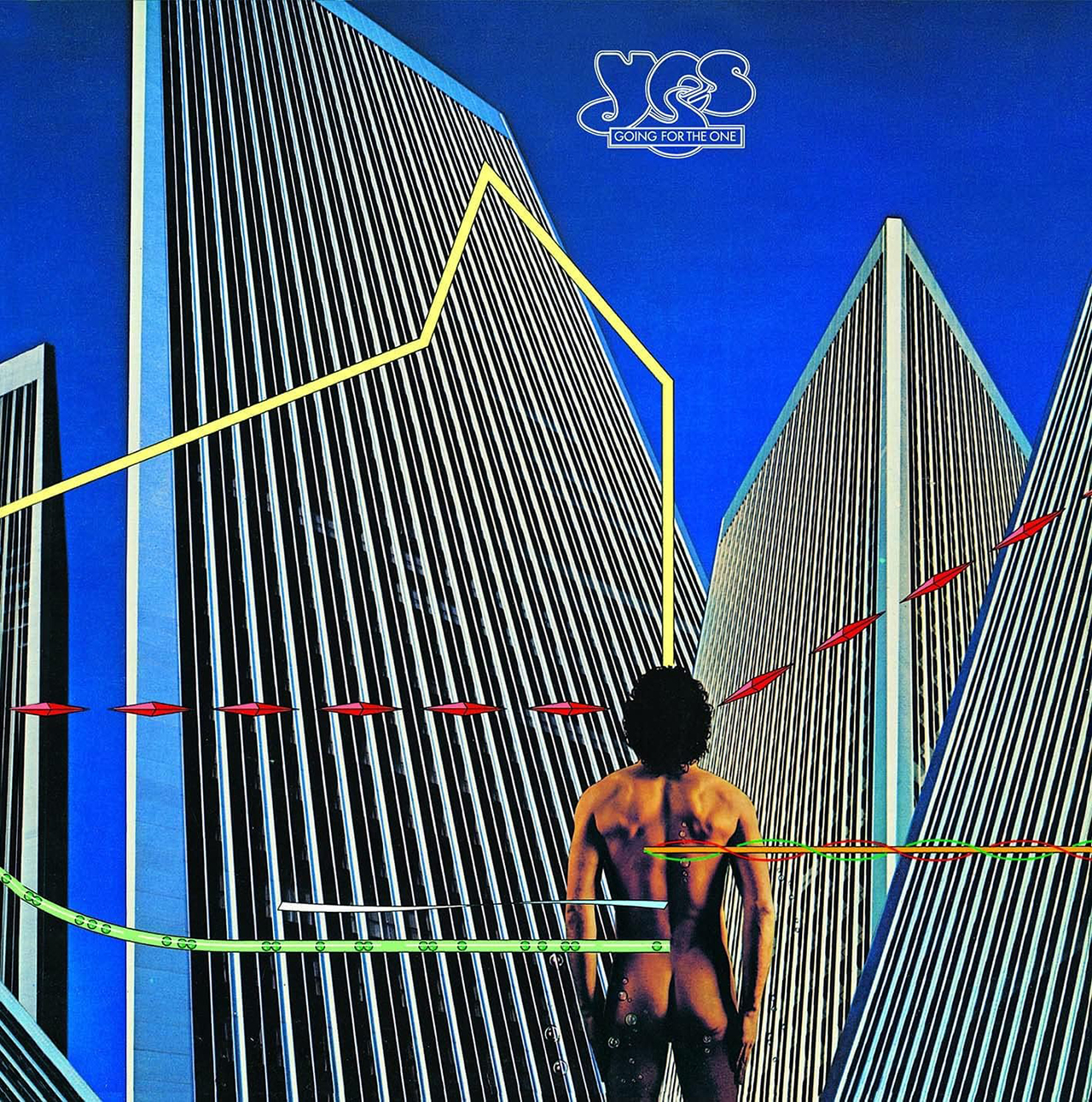

Around this time Hipgnosis took over from Roger Dean and designed Yes’ Going For The One. Did you consider Roger a rival?

No, not at all. Roger was a painter and the covers he did for Yes were very painterly. That was his gig. The irony is when Yes fired Roger, the first thing Jon Anderson said to us was, “Can you do a Roger Dean cover?” Storm and I looked at each other and went, “Oh, God...”

Hipgnosis put a naked man on Going For The One. Storm said he used naked figures on LPs because clothes can date an image, didn’t he?

That’s true, but we were also very influenced by the photographer Bill Brandt, who shot nudes in interesting positions. I’m not quite sure what our naked man for Yes was supposed to be, but Atlantic Records complained it looked “gay.” To give Yes their due, they said, “Fuck you! This is the cover we want.” They stuck to their guns.

Hipgnosis wasn’t just you and Storm. Your third partner, Peter Christopherson (also a musician with Throbbing Gristle, Psychic TV, Coil) was with the company from 1973 until the end.

Peter was an integral part of Hipgnosis. He was a generation younger, he was gay, and he brought a different aesthetic to the work. Storm and I were conservative hippies, really. Subversion was Peter’s thing. You can see it in Wishbone Ash’s New England and UFO’s Lights Out. Classic Peter – shooting a cover for a macho rock band and suggesting something sexual had taken place!

Christopherson is also on the cover of several Hipgnosis albums, isn’t he?

Yes, running down a tunnel on The Lamb Lies Down On Broadway, wearing a Panama hat on Brand X’s Moroccan Roll... We often used friends on our covers. Helen Mirren is on String Driven Thing. I’m on 10cc’s Bloody Tourists with a map stuck across my face.

Peter Gabriel speaks fondly of the work Hipgnosis did for his first three solo albums, but says Storm tried fob him off with Pink Floyd’s rejects.

True. Storm always used to say, “A good idea is a good idea!” We had great fun turning Peter into a melting wax effigy for his third album – everybody, including Peter, sat around scratching Polaroids of his face while they were processing. Peter was always willing to experiment.

Is it fair to say punk was the beginning of the end for Hipgnosis?

Yes. [Designer] Jamie Reid fucked it for us! Tearing up pieces of paper and sticking them on a plain background for the Sex Pistols was not where Hipgnosis was at. Wish You Were Here cost 50 grand. Record companies could now get a good cover for 50 quid. But, of course, we didn’t admit defeat; we carried on. Then compact discs arrived. Storm and Peter saw what was coming before I did.

Hipgnosis became Greenback Films in 1983 and made pop videos for Paul Young, Yes and Robert Plant, and then you and Storm fell out and didn’t speak for 12 years. Just like a rock band, eh?

Exactly like a band. Storm and I fell out over money – what else? Storm was a genius but he was a frustrated filmmaker and he’d overspent on the videos. We went our separate ways. I made videos and TV ads, and took a job as Paul McCartney’s creative director in 1991.

You and Storm reconciled, and you took over as Pink Floyd’s creative director following his death in 2013. Did he pass the baton to you?

Yes. Storm and I had lunch many times towards the end. We’d go to an Italian restaurant and have a laugh about old times. His mind was still sharp; it was just his body that was falling apart. I had my own film company but he said someone had to take over everything to do with Pink Floyd when he was gone.

What made you take the job?

I wanted to do interesting things and put on a major exhibition. Storm had staged a great exhibition in Paris [Pink Floyd Interstellar] in 2003, but I wanted something on a grander scale. I had a meeting with the management – always jocular! – and suggested I take the job for a year on a retainer and see how it went. It was strange at first. I could still hear Storm in my ear, and sometimes I still do.

We could have done Bob Dylan a great service. We’d also have done a brilliant cover for Queen. We tried

Pink Floyd: Their Mortal Remains opened at London’s V&A Museum in 2017 and became the largest exhibition on one subject ever staged there. How did that make you feel?

It was something truly magnificent and I was proud to have been the creative director. But I’d never staged an exhibition before. It was all about teamwork and not having too big an ego and knowing you need other people around to make it happen.

Hipgnosis worked with so many artists; but if you could have designed a cover for anyone, who would it have been?

Bob Dylan, but we never got the call. We could have done Bob a great service. We’d also have done a brilliant cover for Queen. We tried – for their Greatest Hits. But Freddie Mercury didn’t like it. I guess you can’t win them all.