Chris Cornell is a picture of health as he enters the hotel room, his tall, lithe body wrapped snugly in jeans and white shirt.

He looks good for 40 – amazingly good, all things considered. Carrying an easy smile and a packet of cigarettes, he opens the sliding glass doors to let the smoke out and the sounds of LA’s Sunset Strip in. Life is good for Audioslave’s singer.

In an adjacent room his new wife and young baby are testimony to his newly found domestic harmony. The Cornells have flown over from their home in Paris, so that Chris can ride the media hoopla that surrounds the launch of Audioslave’s new album, Out Of Exile.

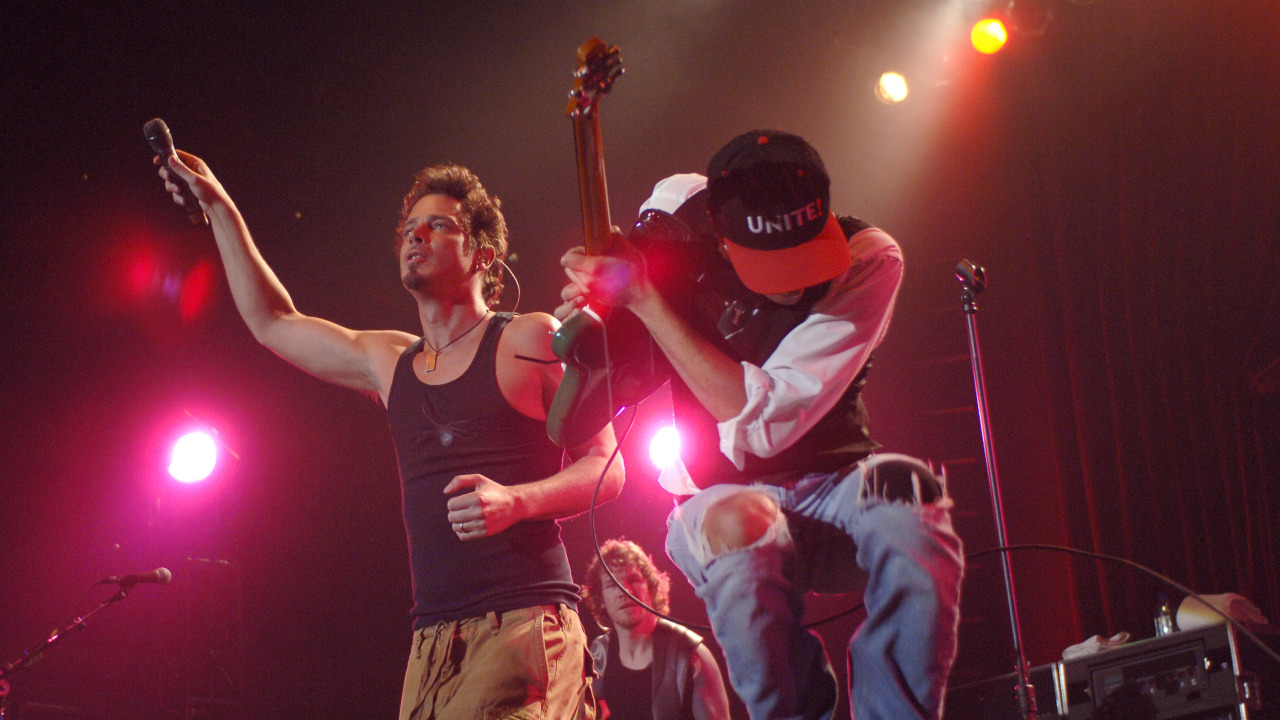

Joining him on the promo merry-go-round is guitarist Tom Morello, a fiercely intelligent and articulate Harvard graduate whose strong political convictions are evidenced by his black T-shirt baring the slogan ‘Arrest The President’.

It has been more than four years since Audioslave rose phoenix-like from the ashes of Soundgarden and Rage Against The Machine. Both men are here to talk about a second album that some questioned would even get made. Ever since Cornell teamed up with bassist Tim Commerford, drummer Brad Wilk and Morello, all ex-Rage members, scepticism has been part of the group, like a shadowy fifth member. But, like every other obstacle Audioslave have encountered, it has been overcome. Now, with Out Of Exile as proof of the group’s defiance and force, there are no longer doubts about their permanence.

For Audioslave there has never been any uncertainty. During their first discussions, Morello made his intentions clear to Cornell: “I said I’m not interested in doing a project, I want the next band I’m in to be the best band I’ve ever been in. So if you want to try something like that, then let’s jam together.”

That meeting was orchestrated by quasi-mystical producer Rick Rubin. “He was a big part of it,” Morello explains. “When Zack [de la Rocha] left Rage, Tim and Brad spent a lot of time over at Rick’s house talking about what we were going to do. Rick made the last Rage Against The Machine record, so he was in our lives a lot then. And one record we would listen to at top volume at Rick’s house was [Soundgarden’s] Badmotorfinger, and we’d go: ‘That guy’s good’.”

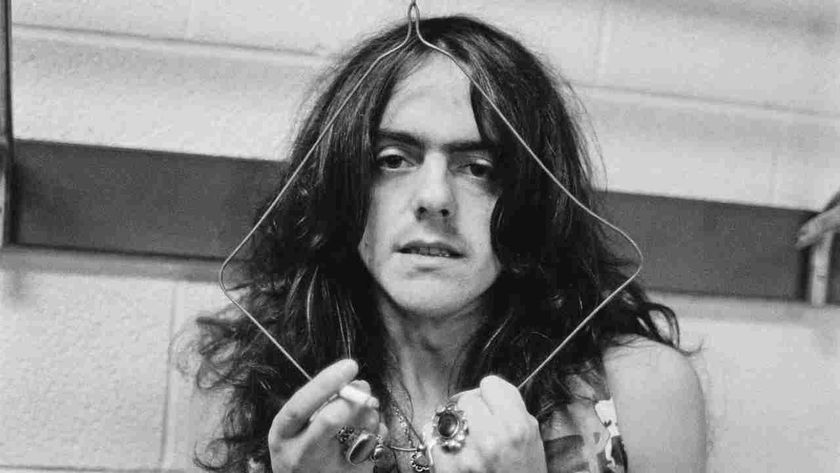

The approach came at an opportune time for Cornell. Since the 1999 release of his critically praised but commercially unsuccessful solo album Euphoria Morning, he had been caught in a downward spiral of drugs, depression and alcoholism. In Morello, Cornell recognised someone who didn’t judge, and who musically had been through the same highs and lows.

Cornell: “One of the main things is the experience factor, because that’s not always a given. We both had very similar experiences, and probably played similar roles in our respective bands. The other thing is that both of us had been through a lot of experiences in being in a band that were negative, that weren’t something we wanted to repeat: ‘I don’t want to have a miserable time either. I want to just do this if it’s fun, and if it’s not fun not do it’. All that stuff came out right away.”

Cornell’s stance was understandable given the pained and acrimonious dissolution of Soundgarden, the group he’d fronted for 12 years until their break-up in April 1997. For Morello, Commerford and Wilk, the demise of Rage Against The Machine had been equally turbulent, their eight-year career ending abruptly in October 2000 when de la Rocha announced he was leaving to pursue a solo career. These unhappy experiences were still fresh in the minds of the four members of Audioslave when they got together in 2001.

But whatever trepidation they may have felt was quickly dispelled by an unprecedented creative outpouring. As Wilk explains: “We went from writing three records in 12 years to writing three records’ worth of material within 24 days.”

“In the rehearsal there was no history or anchor from our previous bands,” Morello adds. “It felt like a new garage band, friends in a room: ‘How do you like this one?’. ‘How do you like this idea?’. It felt very innocent and easy to write the songs that way.”

The adjustment was different for Cornell, however. Not only was he joining three people who had a long history together, but he was also effectively replacing a very contrasting style of vocalist. “I knew if I went in and sang over something that could easily sound like a Rage Against The Machine song, it’s not going to sound anything like Rage Against The Machine,” he recalls.

The initial rehearsals proved so fruitful that the band settled into a pattern, which continued with the second album, of being able to write a new song every day. But although things were flourishing musically, the business side of things was threatening to sabotage Audioslave.

Shortly after their productive songwriting spurt, Cornell walked out. “What caved in on me was I had a lot of personal crisis stuff going on, and a lot of what we talked about in terms of this being fun and uncomplicated started to become un-fun and very much complicated by the two separate management camps, and they were disagreeing with each other and throwing the burden of sorting all of this stuff out on to the band.”

In the end, after failing to get the respective managers to resolve their issues, the band hit on a solution: they fired them. “It became staggeringly simple after that,” Cornell adds.

With new managers in place, Audioslave were able to get back to making music. With the help of Rick Rubin, they whittled the original batch of songs down to the 14 that made up their 2002 self-titled debut. The album married Cornell’s sunless, soul-searching lyrics and rasping wail to some apocalyptic riffing and spleen-tingling rhythms. The reaction was mixed; the Rolling Stone review concluded: ‘In their past lives, the members of this band were enraged. Now, fierce as they might sound, Audioslave just seem sorta engorged’.

It was hardly the first snipe at the band, who had found themselves in the cross-hairs of critics’ sights from the moment the rumours of Cornell collaborating with the ex-members of Rage were confirmed; ‘supergroup’ is a label they seem destined never to escape. It’s also not one that seems to worry them unduly.

“At this point I think it’s good,” Cornell states, “because if you can take something that absolutely only has negative connotations and present an example that’s not awful… Also, I like to point out bands like Led Zeppelin came from other bands that had success. Where ‘supergroup’ became a bad thing was in the 80s where you had Power Station and Asia and Damn Yankees, where it seemed like a convenient way to remarket the crap that these idiots already did. And with absolutely no dedication towards making great music or continuing on in a new way that’s as vital as something they did in the past. It’s just more of: ‘I miss the cameras and I miss the fans and the shows, let’s get together’.”

Both Soundgarden and Rage Against The Machine were recognised for breaking new ground musically. And while Audioslave harness elements of their members’ former bands, few would cite their music as being radically innovative. It’s a point Morello is prepared to concede. “I’d say one of the reasons there may be some truth to that is because that ground was broken by those initial bands. The idea of making intelligent hard rock music is something that didn’t exist before Soundgarden so much; the idea of interracial hard rock bands breaking down the ethnic classifications between musics, stereotypes between musics, did not really exist before Rage Against The Machine. Those fertile fields that bands now sow their seed in were tilled by Rage Against The Machine and Soundgarden. We are a band now that makes music with the same kind of uncompromising integrity that we did in Soundgarden and Rage Against The Machine. It does not stand in such stark contrast to the musical scene now, in part because of the work our previous bands did.”

Audioslave’s new album Out Of Exile contains the song Your Time Has Come that is a very personal reflection by Cornell on the many close friends of his who have died. In writing about the likes of Jeff Buckley, Mother Love Bone singer Andrew Wood and Alice In Chains’ Layne Staley, Cornell was all too aware that through his own dalliance with drugs he might easily have joined their number. “I was in my early 20s when my first close friend died of a drug overdose, and I was devastated. He [Andrew Wood] was a creative force in music, and I felt like a kindred spirit had vanished. As time went on, that kept happening. And I think by the time it was Layne Staley [April 2002] I was Roger Waters. I’d constructed the enormous cement wall of ‘I’m not going to feel this. I don’t want to think about it. It might be me next. I don’t care. If it’s not me, great. If it’s me, I don’t care’.”

Perched as he was on the precipice, Cornell was able to pull back just in time, thanks to Audioslave, the other members of which he has openly said saved his life. “I think in the sense that at the time when we came together, and particularly the time that we reconvened and hired new management, and we were a band and I was able to focus on something really positive, nothing else in my life was positive. I was in a horrible relationship, I was struggling with alcohol and drugs in a way that I never imagined I would. I always felt like I was a really good person deep down, a person of integrity, the most together person in my circle of people. Then I became one of those people that is the least together. I was anchored by the other three guys in this band, who were very supportive in every way, in a friendship way which I needed and which I didn’t really necessarily have outside of that. It was hugely important.”

With a new lease of life, Cornell was determined to focus his energy on music, and in the process return the favour shown by the others through their faith in him. “Something that came out of that in me was that if I have a positive relationship with people I’m close to, I’m going to do my absolute best to repay that. When we go into a room to write a song, I want to contribute in a way that I feel good about personally, but I also want to contribute in a way where these guys leave the rehearsal room going: ‘God, I’m so stoked that we’re in a band with this guy’. And I think that had a huge impact on me.”

The collaborative input of each member is something they are all excited about and keen to stress. For Cornell, it’s clearly a refreshing change from past experiences. “Soundgarden started that way,” he says, “but by the time we were really making records, even from Louder Than Love, which was the first A&M record, we started splintering off and writing songs at home, and that began for me the lonely period of a lot of demoing in basements.”

Wilk, too, is aware of the improved writing process with Audioslave compared with Rage: “It’s definitely more collaborative, and it’s definitely more satisfying in that I feel that anybody can bring anything in, and if someone doesn’t like it everyone will at least still work on it and see the idea to its fruition and then decide if it works or not. A lot of times in Rage Against The Machine it was just ‘I don’t like rock’, or ‘I don’t like this riff’, and ‘Let’s not even try and make it better’. It was definitely more of a battle creatively. And that’s one of the reasons it just stopped working.”

Four years after their much-publicised and troubled birth, with a new album out and a tour under way, Audioslave believe they are only now hitting their stride. “Interestingly enough I feel like we’ve just arrived,” Wilk says. “We came from two bands that had a lot of history, so before anyone got the first record people had preconceived notions of what Audioslave was. But I feel for this record, people aren’t thinking about Soundgarden and Rage Against The Machine, they’re thinking about the new Audioslave record, so it’s completely different.”

In describing the album, Wilk uses the food metaphors: “To me, the first record was the skin on the fruit. I feel like for this record, you get to bite into the fruit of Audioslave.”

Out Of Exile is a symbolic title for the new album. It suggests the creative and personal liberation Audioslave are now enjoying. With the group at an early stage of their evolution, where do they see the future taking them? “The sky’s the limit,” Morello says excitedly. From the elevated height of the Los Angeles hotel room, the sky appears very close.

This was first published in Classic Rock issue 81.