June 2, 1969: prog rock hopefuls Mandrake Paddle Steamer squeezed onto the stage of a home counties ex-servicemen’s establishment and made history as the first band to play Friars Aylesbury, the legendary club currently celebrating its 50th anniversary year.

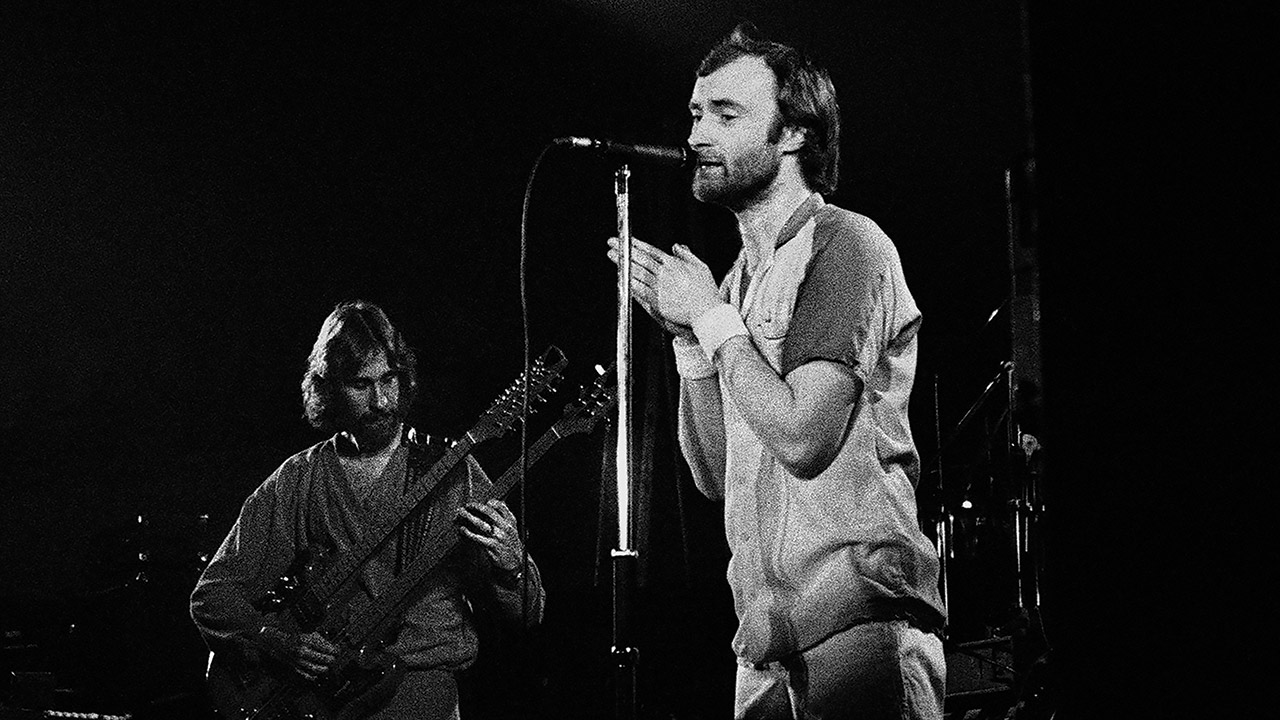

Mandrake didn’t get beyond one single but Friars became a progressive rock stronghold as its unusually enthusiastic crowd embraced names such as King Crimson, Van der Graaf Generator and East Of Eden, all but adopted the early Genesis, encouraged Bowie to unveil Ziggy Stardust and ignited the ascension of Marillion.

Flying by the seat of its pants from week to week, Friars survived through sheer musical passion, echoed by regulars prone to judge that week’s act by what limb-flailing reaction was sparked in ‘Leapers’ Corner’. John Peel liked it so much he waived his DJ fee so the following week’s first hundred punters could get free admission and then recently launched Zigzag magazine called it the UK’s best club.

The idea to start Friars came from Aylesbury Grammar School teacher Robin Pike. The first his pupils heard about Friars was when Mr Pike engaged one to design its membership card. A veteran club-goer, his vision came seeing the likes of Cream, Otis Redding and Nina Simone at Brixton’s funky Ram Jam Club and Peel hold weekly court at Mothers in Erdington, Birmingham.

“We all sat on the floor and he played records,” recalls Robin. “It was a real hippie thing, everybody there together. The feel of the music was amazing. Put the Ram Jam with Mothers and I understood what a club could be; maybe there could be something like that in Aylesbury?”

Since 1967, Robin had run coach trips from the school to key London concerts, including Hendrix at the Royal Albert Hall, and organised Christmas dances. His club dream catalysed after meeting David Stopps, then managing a local blues band who played at 1968’s dance. “I said, ‘Why don’t we start a club in Aylesbury?’ I felt sure there was an audience. There’d been a friarage in Aylesbury and it lent itself to an image.”

They found a venue at Aylesbury Ex-Servicemen’s Club’s small functions hall. The usually dead Monday night was available which, according to David, worked to their advantage because few bands had gigs that day.

Robin hired hip DJ Andy Dunkley after witnessing him soundtrack the Roundhouse’s Sunday all-dayers with shrinkwrapped imports and advance pressings but, due to his respectable day-job, David became Friars’ full-time promoter.

After the opening night (headlined by Mike Cooper), Friars went on to present the cream of the UK underground circuit with Pretty Things, Free, Blossom Toes, former Tull guitarist Mick Abrahams’ Blodwyn Pig and Jody Grind appearing in its first weeks.

“[Friars] was the most revered gig to do for bands of our ilk,” said Blossom Toes guitarist Brian Godding, “a safe haven as most UK venues could be quite dangerous to work in. It was the Mecca of the musical movement of the period. Bands felt safe in the knowledge they were among ‘likeminded people’… You could go and try out all your new weird and wonderful ideas without getting thumped or threatened!”

Weekly flyers revealed coming attractions, accompanied by David’s hippie expounding. “Next week we have King Crimson,” said July 21’s newsheet. “It’s now quite clear that this band is going to be enormously big very soon.”

He was, of course, right. The following week’s Crimson visitation birthed the ‘Friars Band’; those acts the crowd loved instantly and who regularly returned. The buzz around Crimson was building after the Stones’ Hyde Park concert three weeks earlier, Robert Fripp, Greg Lake, Ian McDonald and Mike Giles drawing 400 punters into a venue comfortable with half that.

“I heard them on Peel [John Peel’s BBC Radio Show],” recalls Stopps. “Everyone was saying they were fantastic. Next we’d got them for 30 quid! It was the most people we ever had in that venue. They were incredibly impressive.”

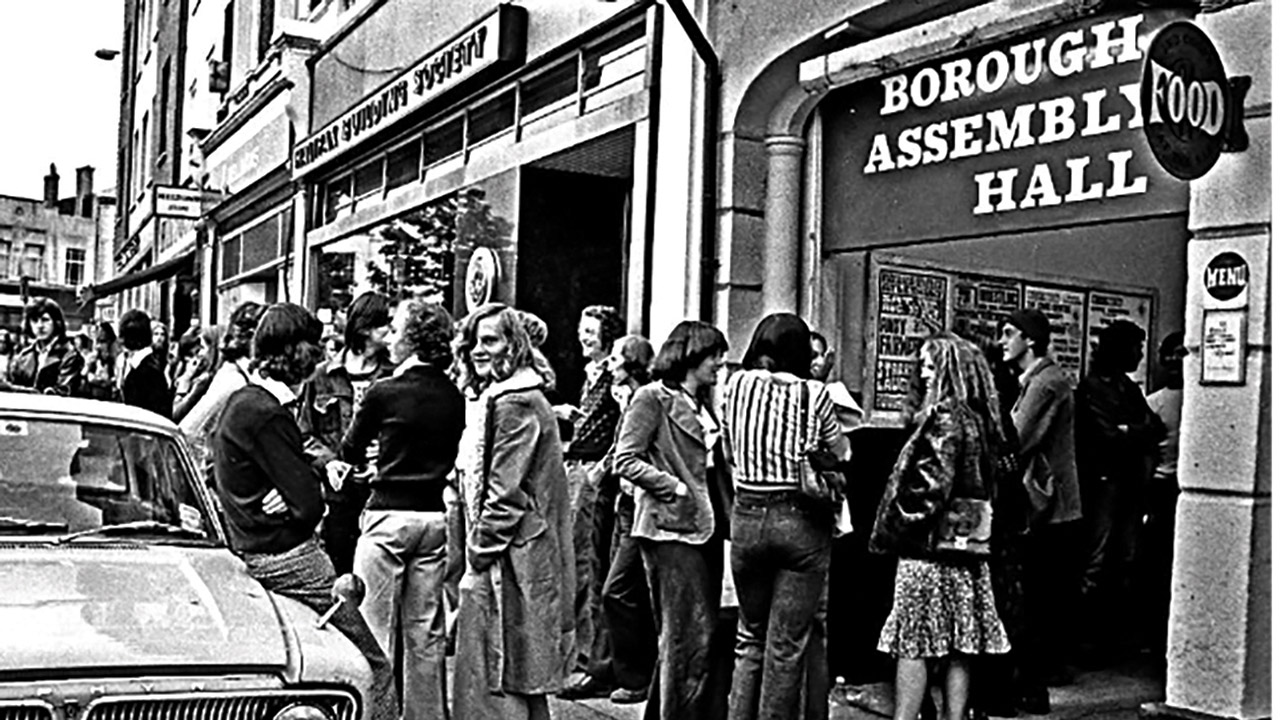

East Of Eden became the next ‘Friars Band’ in August, returning three times and launching larger events at the Borough Assembly Hall. Playing the recently released Mercator Projected, EOE epitomised progressive rock, mixing jazz, rock and classical elements into roof-raising blow-outs, transforming Friars into a mass barn-dance when violinist Dave Arbus resorted to Irish jigs in the encores (inspiring 1971’s hit Jig-A-Jig). Week-by-week, the club witnessed the birth of ‘prog’, through organ colossus Graham Bond, Third Ear Band, Principal Edwards Magic Theatre, Writing On The Wall, Keith Relf’s Renaissance, Caravan, High Tide, Quintessence and Hawkwind (whose debut album was still months away).

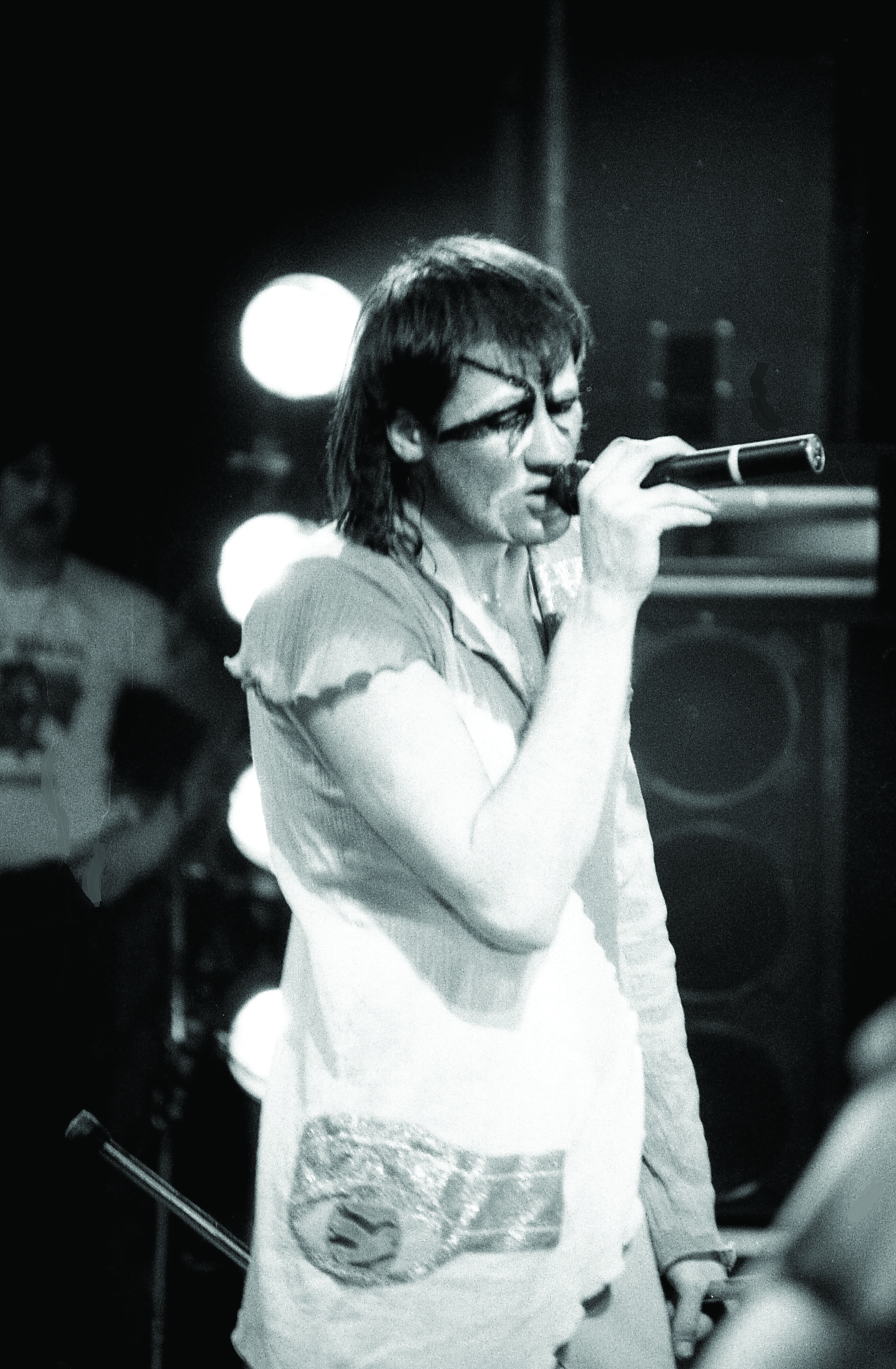

Van der Graaf Generator joined the ‘Friars Bands’ after debuting that November, Hammill stalking the tiny stage snarling Necromancer with rare intensity, flanked by thermonuclear sax titan David Jackson simultaneously playing alto and tenor. Undoubtedly, the heaviest band that first year (including an unknown Black Sabbath playing to 50 people). “They immediately connected with the Friars audience,” says Stopps. “It’s the audience-artist symbiotic relationship; we’d set up the infrastructure for that to happen, and it certainly did with Van der Graaf.”

VdGG consolidated Friars’ burgeoning relationship with nascent Charisma Records, soon to release The Least We Can Do Is Wave To Each Other, also solidified by Rare Bird’s sole appearance in January 1970 (before Sympathy became a hit). It exploded when Genesis debuted in April (supposedly supported by Nick Drake); love at first sight as, nervously approaching his mic and foot-operated bass drum, Peter Gabriel riveted the crowd with surreal introductions before guitarists Mike Rutherford and Anthony Phillips, and organist Tony Banks, launched into songs ready for recording on Trespass, including Stagnation and the storming The Knife.

Genesis were received so well they were rebooked for June, appeared at that year’s school dance, Friars’ satellite gigs, and in its 1971-1975 location, the Borough Assembly Hall. “Friars is the best gig in the country,” said Gabriel.

“We were told Genesis would be suitable and they were fantastic,” recalls David. “We paid them £10, then 15, 30, 40, 50 and 75, until I gave them 100 at Bedford Corn Exchange. Peter shook my hand onstage and said, ‘I want to thank this man; he’s the first person who’s ever paid us £100.’ Then he started the set! One of the most extraordinary gigs was Princes Risborough British Legion Hall in 1970; the equipment broke down so Gabriel did this chant while they tried to fix the gear. Years later, it evolved into Biko.

“One time they were doing so badly I thought they were gonna split so we had a Genesis convention at Watford Town Hall. Gabriel gave out rosettes saying ‘Genesis Convention’. Melody Maker’s Chris Welch wrote this fantastic review that inspired them to move forward. In retrospect, I probably could’ve managed them; an opportunity I didn’t see, even though it was staring me in the face.

“In June 1971, Gabriel leapt four feet off the Friars stage and broke his ankle. That audience seemed to excite people! He thought people would break his fall but everyone parted and he landed badly. The audience threw him back onstage and he finished the set on his knees. When the rest of the band left the stage, he couldn’t move. To this day, he says: ‘Those bastards just left me there!’ I remember him sitting in agony waiting for the ambulance. Later, he wrote in our magazine, ‘I’ll always remember Aylesbury very fondly; I got the best two screws I ever had. They’re four inches above my heel and will be with me until the day I die’.”

“Genesis were great in every way. When they came back in 1980, fans queued outside for three days. We had cricket matches and wheelbarrows full of porridge. We presented them with a cup that night.”

Friars held “foreign” gigs in nearby towns like Watford, Bedford, High Wycombe and later Dunstable (where Pink Floyd had rescued the club in November 1969). New supergroup Emerson, Lake And Palmer opened Friars’ Watford Town Hall satellite gig on September 24 (two months before their debut album) having recently played 1970’s humongous Isle of Wight Festival. “That was their moment,” recalls David. “I announced them and there was this huge reaction from the audience. Friars was on the circuit now. If a band went on tour and weren’t playing Friars they wanted to know why. You had to do Friars Aylesbury.”

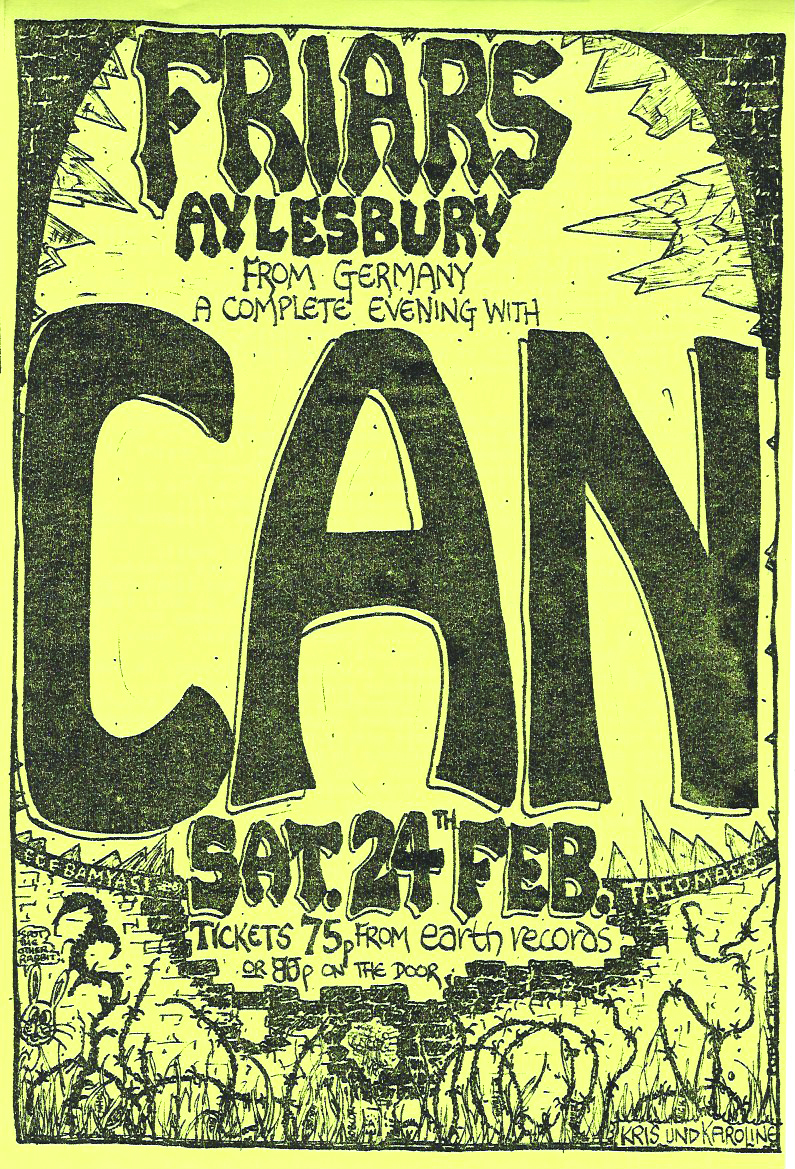

After relocating to the larger Borough Assembly Hall and shifting to Saturdays in April 1971, three landmark Bowie gigs “really put us on the world map. We had lots of publicity in America. We were just in a great place really.” Along with returning early favourites, Friars presented names including Queen, Hawkwind, Can, Focus, Gong, Man, Roxy Music, Camel, Spirit and many more until moving to Aylesbury’s new Civic Centre, opened by Greenslade in September 1975.

Riding punk’s impact, Friars continued presenting Tangerine Dream, Steve Hillage, Renaissance, King Crimson, Camel, Procol Harum, Curved Air, Peter Gabriel and Manfred Mann’s Earth Band. But the club’s 80s success story came from the local pub circuit: Marillion.

Pete Trewavas was a familiar local face who’d worked in Stopps’ Earth Records and local bands including Orthi, the Robins and the Cameras. Arriving from Scotland, Fish was soon another familiar character, seeking to reinstall the lyrical qualities of Peter Hammill into a music business shying from prog until Marillion led its resurgence.

“Fish used to come to Friars and invited me to see them in the local Britannia pub,” recalls Stopps. “They were very good; very early Genesis. They had so much enthusiasm, were doing original material, Fish’s lyrics were great and the music was dynamic. It was a great band to have come from this area. They always say Friars was a massive influence on their career.”

Marillion started by supporting punk poet John Cooper Clarke in May 1981, then Spirit in August, John Martyn in October and John Otway the following February. By June, they merited their first Friars headliner. A year later Hammill was supporting them, followed by Otway when Marillion played the last show of Friars’ first run before it stopped for 25 years because Stopps was busy managing Howard Jones.

“We put them on a lot in those early days,” recalls Stopps. “I managed them for six weeks in summer ’82 after Fish begged me to. I was very busy with Friars but really did my best; got them a residency at the Marquee and talking to EMI. Then Fish decided I wasn’t spending enough time on them. They had this rule everybody in the band had to agree on every decision. All the band wanted me to carry on, apart from Fish and they went to John Arnison. Market Square Heroes was the first song they released – dedicated to me because they felt bad about firing me.”

There’s no need to explain what happened next. “Everyone thought it was over when Fish left but Steve Hogarth came in and they started building it again,” says David, who restarted Friars in 2009 at the Civic Centre before the Waterside Theatre became its modern home, Marillion selling it out in 2013 and 2017 (Hogarth instrumental in the successful campaign for a Bowie statue in that much-fêted Market Square).

King Crimson returned in 2015 and 2016. “That was Jakko [Jakszyk], basically,” says Stopps. “He says seeing [Crimson] at Watford Town Hall in 1971 was the start of his career. After that he knew he was going to be a musician. He contacted me, they did two nights in 2015, the band loved it and it was the only two British dates they did in 2016. Kate Bush came and, rumour has it, Bowie came in, saw the gig and left, but that’s not proven.”

2018 saw Camel return and 2019’s 50th celebrations were dropkicked into the cosmos by Nick Mason’s A Saucerful Of Secrets last April (49 years since Floyd appeared at Friars Dunstable). “That was just amazing,” says Stopps. “I can’t believe he’s out there still doing it, or I’m out there still doing it. It’s extraordinary; I’d just turned 21 when we started Friars. I’m 71 now and it’s 50 years. Obviously, there was a gap when we didn’t do anything but I always thought somebody else would take over and they never did. It’s bizarre. It really is driven on enthusiasm for music.”

November saw the return of Steves Hillage and Hackett, the latter playing Selling England By The Pound on his Genesis Revisited jaunt. “I’ve good memories of playing Aylesbury many times,” says Hackett. “It was the sure-fire gig that was always going to work for us. Of course, we had a long way to go, but there was a sense of Friars being ahead of the rest of the world.”

This article originally appeared in issue 105 of Prog Magazine.