They hanged a young black man in Lexington, Mississippi. He was castrated, then the mob dragged his mutilated body up and down the street behind a car, as a teenage boy called Riley B. King watched from the sidewalk.

It’s no wonder the blues flourished in a time and place where just having a black face could get you killed. “I grew up knowing that I didn’t have a name but ‘boy’,” says B.B. “‘Come here boy! That’s your name.’ There were certain rules you grew up knowing about. If I saw a white man at that time and didn’t know him, I’d get off the street and let him pass by.”

Racism is still prevalent in the Deep South, as it is all over, but attitudes have changed over the years [“I was shocked more than most white people to find we had a black President!” laughs B.B.] as The King of the Blues was to discover one life-changing date in the late 60s. It’s early in the afternoon on Sunday February 26, 1967. An old International tour bus nicknamed Big Red rolls up to the Fillmore Auditorium in San Francisco, California. As the bus comes to a halt, B.B. King and his entourage peer out of its side windows at the ‘same old funky building’ they’ve played countless times before. On this occasion, the clientele strikes them as unusual. Instead of the mature, well-dressed black patrons they’ve played to since forever, there’s a bunch of scruffy white kids lounging around the Fillmore’s entrance.

“They had long hair,” says B.B. King. “They were sitting out there on the stairs that led to the doorway of the Fillmore. I told my road manager, ‘I think my agent’s made a mistake.’ All these guys, with the long hair, they didn’t seem to be bothered with us at all.”

The Fillmore is run by impresario and promoter Bill Graham. A champion of the counter-culture scene, Graham and his venue host shows by the likes of The Doors and Jefferson Airplane. He will abandon the Auditorium a year after B.B. plays there to open the larger capacity Fillmore West and Winterland Ballroom venues, both in San Francisco; and the Fillmore East in New York City. In the meantime, back at the original Fillmore, B.B King is looking for answers.

“I sent my road manager and told him to tell Bill Graham I was there but I thought it was the wrong place. So, we were gonna leave,” says B.B. “Bill came back out with the road manager, came on the bus and said, ‘You’re at the right place. Get ready and I’ll take you in.’ I followed him into the same old dressing room. I remember that somebody had took a knife and cut the seat. That happened before Bill bought the place but he hadn’t fixed it (laughs). Anyway, we started to talk and he told me what he wanted me to do.”

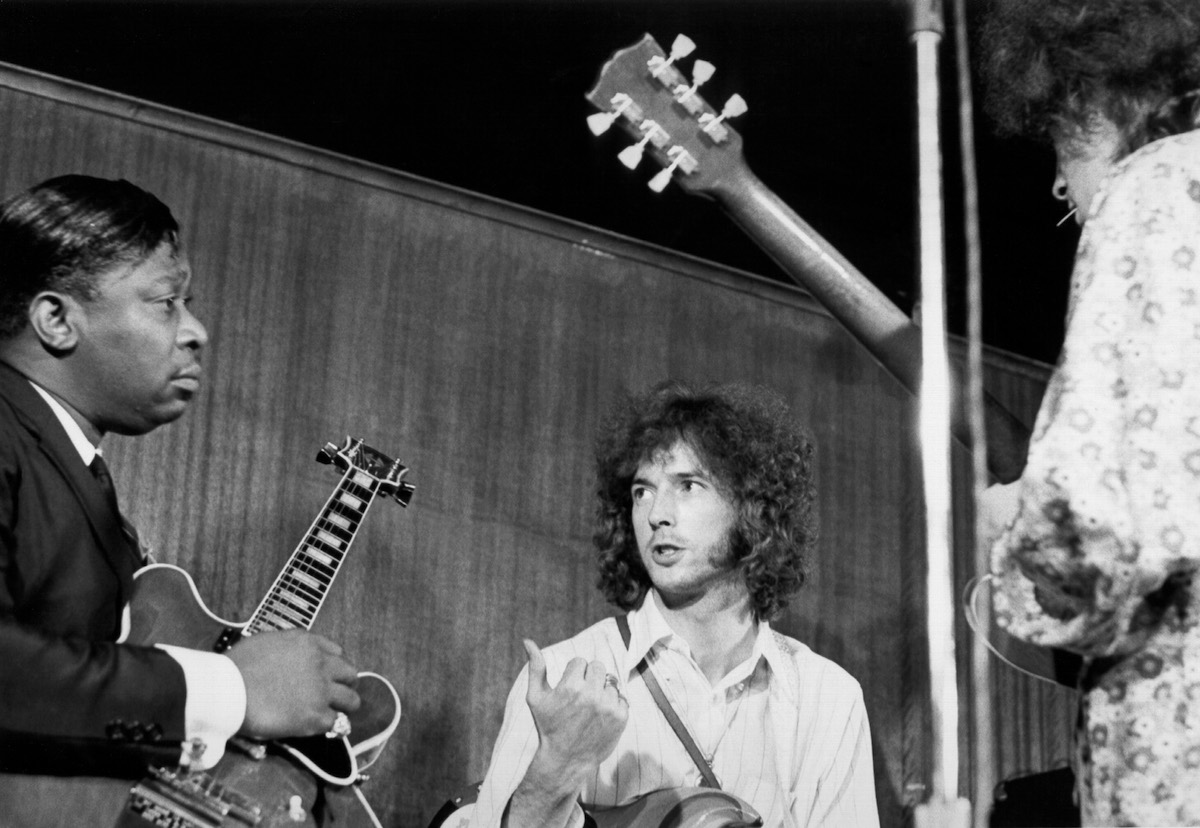

B.B. and his band are the headliners for this ‘one night only’ show with support from psychedelic group Moby Grape and The Steve Miller Blues Band. Miller himself is making his debut at the Fillmore that afternoon. As it dawns on B.B. that he has been booked to entertain a young, predominantly white rock audience for the first time in his life, he can feel beads of cold sweat running down the back of his neck. His heart begins racing. His throat goes dry.

“I said to Bill, ‘Man, I can’t handle it. You gonna have to get me a bottle,’” he laughs. “I was drinking then. Bill said, ‘Dude, we don’t sell it.’ I said, ‘I didn’t say nuthin’ about selling it. Get me a bottle!’ He looked at me and said, ‘OK’ and sent someone over with a miniature bottle. I wanted to tell them to send it back but I didn’t. I tried to keep my cool.”

While the support acts do their thing B.B. can only sit and wait. “Bill said, ‘I’ll come back for you when it’s time to go on,’” he says. “So, I grab the bottle and I go glug, glug, glug [laughs], cos I’m nervous as a cat with about six dogs around him. Finally, Bill sent up a message to me to say he’d be up for me in five or ten minutes. He was a no nonsense guy. Whatever you had to do you do it and we ok. That’s the way he was.

“So, I sit there like I’m on pins and sure enough he came and got me. I followed him down to where the bandstand was. He walked out on the stage and said ‘Ladies and gentleman… – and I swear, you could hear a pin drop – ‘I bring you The Chairman of the Board, B.B. King.’ I’ve never been introduced like that before or since.”

B.B. walks out onto the stage as the auditorium’s floodlights capture a sea of kids rising to their feet. “When we used to play the Fillmore [when a guy named Charles Sullivan owned it], it had chairs and tables and stuff,” remembers B.B. “Now, all the kids were sat on the floor and when Bill mentioned my name they all stood up. For three or four tunes after that time, they would stand up after every tune.”

Nervous to the point of near collapse, B.B. is suddenly hit by the size of the audience. At this point in his career he is mainly playing small club dates, with around 200 to 250 people in attendance. The Fillmore Auditorium holds more than a 1,000 souls.

The enthusiastic response from the audience, coupled with his nerve-wracked demeanour, proves too much for B.B. to handle and he breaks down. “I was so touched I cried,” he admits. “Cos I was thinking, ‘what am I gonna do with all these kids out here?’ They didn’t know who I was when I was walking through the door, but they had heard of me, they knew about me and for some reason they seemed to think that I was pretty good as a guitarist.”

B.B.’s stock is running high with young rock fans in the late 60s. It’s just that he doesn’t know it yet. When kids ask white American blues guitarists like Mike Bloomfield (of Paul Butterfield Blues Band fame) how he learned to play the blues the response was invariably, ‘B.B. King’.

Now, the Fillmore audience has at last had its opportunity to pay respects to The King of the Blues, and as an emotionally drained B.B. hits his last note of the night, soaks up the applause, then turns to leave the stage, he breaks down once again.

B.B. broke the seal at the Fillmore Auditorium. All of a sudden there was no such thing as a typical B.B. King fan or blues listener in general. The whole white audience discovery thing that had already boosted the careers of John Lee Hooker, Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf and a host of obscure Delta blues artists dragged out of retirement, had passed B.B. King by.

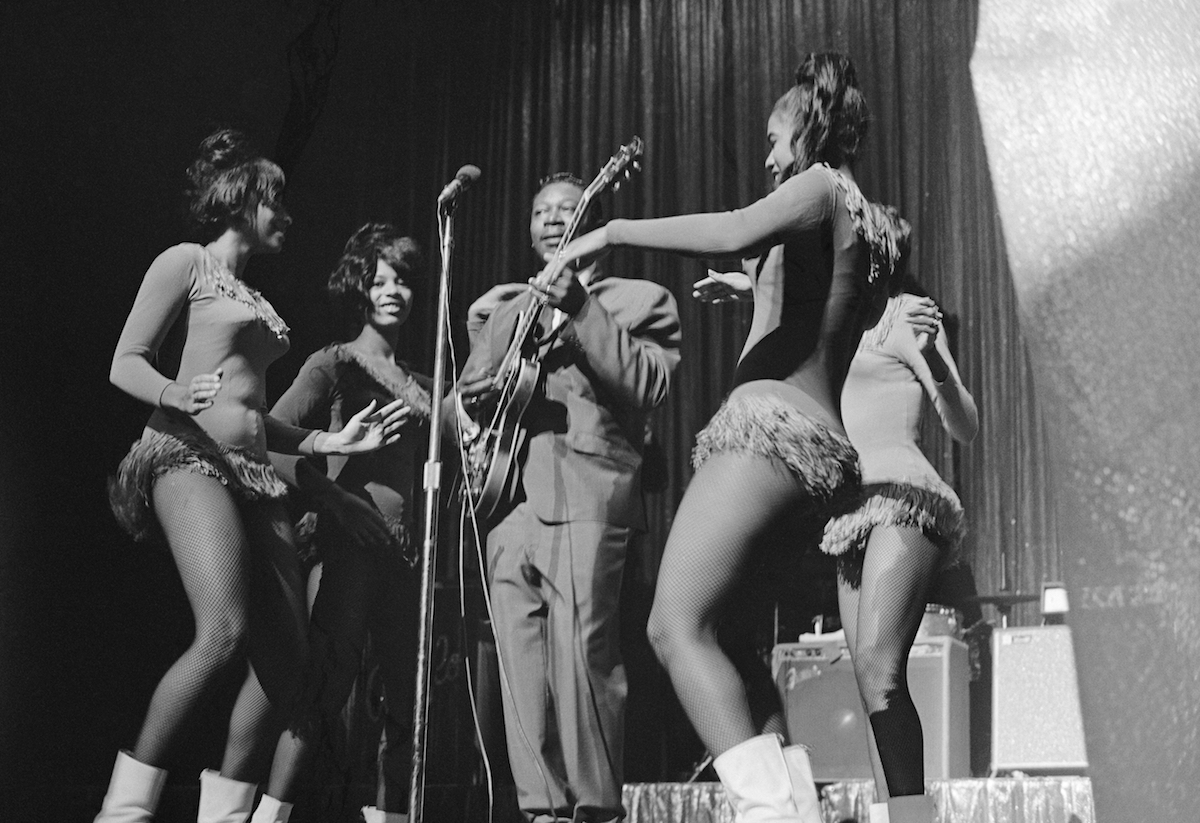

The reason for that is that B.B. was a progressive musician. He moved with the times to keep one step ahead of the needs of his black audiences. They didn’t want a folk blues revival. B.B.’s audience had sophisticated tastes. They wanted horns, strings, backing singers… the whole nine yards. B.B. wasn’t about to start looking back.

It’s only in recent years that B.B. King has even allowed himself to pause and reflect on his illustriuous past. Hence the 2008 opening of his B.B. King Museum and Delta Interpretive Centre in his old stomping ground of Indianola, Mississippi.

There’s the forthcoming movie – _The Life of Riley _[see boxout on page 45], directed by Jon Brewer – which sees the film maker burrow into every aspect of B.B.’s past. And there’s this feature, where B.B. and pals like Eric Clapton, John Mayall, Mick Taylor and others discuss his amazing history and why he’s still so reverred 63 years after he cut his first record.

The story begins with B.B. King’s birth on September 16, 1925. “I was born, according to my Dad, between Indianola and Itta Bena in Mississippi,” says B.B., who was christened Riley B. King. His father Albert described the exact location of his son’s birthplace (just outside of Berclair in LaFlore County) to B.B’s biographer Charles Sawyer, shortly before he died. “My dad led us there by tape recorder. By telling Charles how to get there he was able to lead us – and my bus – all the way to where I was born.”

According to B.B, his parents split up when he was around five years old. There was also a brother who died, of whom he has no recollection. His father moved on while his mother, Nora Ella Farr, took the boy Riley to live with his maternal grandmother, Elnora Farr, in Kilmichael, Mississippi. “I had nothing to say about it,” says B.B. today. “She carried me with her.

“My mother carried me to church every Sunday too,” he laughs. “I didn’t like to go. She made me go cos whatever my mother said to do was done! I loved her but she was strict… very strict.”

Funnily enough, B.B.’s attitude to Sunday morning scripture meetings soon changed.

“I started to see girls,” he laughs. “I would see them sitting down at the front of the pulpit and I got to wanting to go to church! Every time they had a meeting each Sunday I would be one of the first to go in because there was girls there. I’ve liked girls all my life.”

B.B. was also keen on his pastor, the Reverend Archie Fair – but for very different reasons, obviously. “I liked him because he played guitar,” says B.B., of his first stirrings of interest in the instrument. “I liked the way he played, sang and preached in church. He had a style of his own and I liked it.”

B.B. always gave credit where it was due, claiming that he got his guitar style by trying to sound like T-Bone Walker – and failing. It was also T-Bone that inspired the kid to get an electric guitar, after B.B. met him at WDIA radio station.

The credit for giving him the guitar bug in the first place, however, falls to the good Reverend Fair. “I remember when he would visit my uncle. My mother’s brother was married to the preacher’s sister. He would always lay his guitar on the bed – the soft parts of the bed – and I’d bother with it while they was eating dinner. The adults would eat first, before they would let us kids eat. Well, one day they got through eating sooner than I thought and they caught me with the guitar. My uncle was a mean guy. He figured he’d get ready to beat me up. My pastor begged him not to bother me. He didn’t, and from that moment I adored Archie Fair [laughs].”

Life for Riley was good for a while, but blues-inspiring heartache was on the way. B.B.’s mother passed away when he was nine and a half years old. His grandmother died two years later. “I felt deserted,” says B.B. “When she died, there was no one to live with that I wanted to live with. My uncle still lived in the area, and I had an aunt that lived in the area, but I didn’t like either of them to live with.”

So Riley spent two years on his own – working as a sharecropper – until his father came back into his life. “When he found out where I was, he came back. I was still a minor. He was married again and had four more kids.”

Albert took his son to his home in Lexington, Mississippi to meet his new siblings: “I had been living with other people all of my life. So I learned to live and tried to get along with everybody because there’s one of me… and four of them.”

Unfortunately, happy families was not on the cards for B.B., and he was soon on his own again: “I didn’t like my stepmother,” he explains. “I later found out that she was a good woman. It was me. I didn’t understand her and didn’t like her.”

B.B. rode his bicycle from Lexington back to Kilmichael, a journey of about 100 miles. “When I got up there all of the blacks had left,” he recalls. “So, I went back to the Delta to pick cotton just as the war was starting. I fell in love with a girl called Martha, did basic training, and got married. I was 18. She was 17.”

King was already singing and playing guitar with gospel group The Famous St. John’s Quartet, based in Inverness, Mississippi, when a silly accident forced him to go on the run to Memphis, Tennessee. He somehow damaged the exhaust on a tractor and, fearing that the plantation owner would ‘kill him’, he took off.

One big misconception that gets on B.B.’s nerves is his relationship with Delta bluesman Bukka White, with whom he first hooked up on that unscheduled trip to Memphis.“Bukka was not my uncle!” shouts B.B., hoping he’s cleared this one up once and for all. “He was my cousin– my mother’s first cousin. My mother’s mother was a sister to his mother [laughs].”

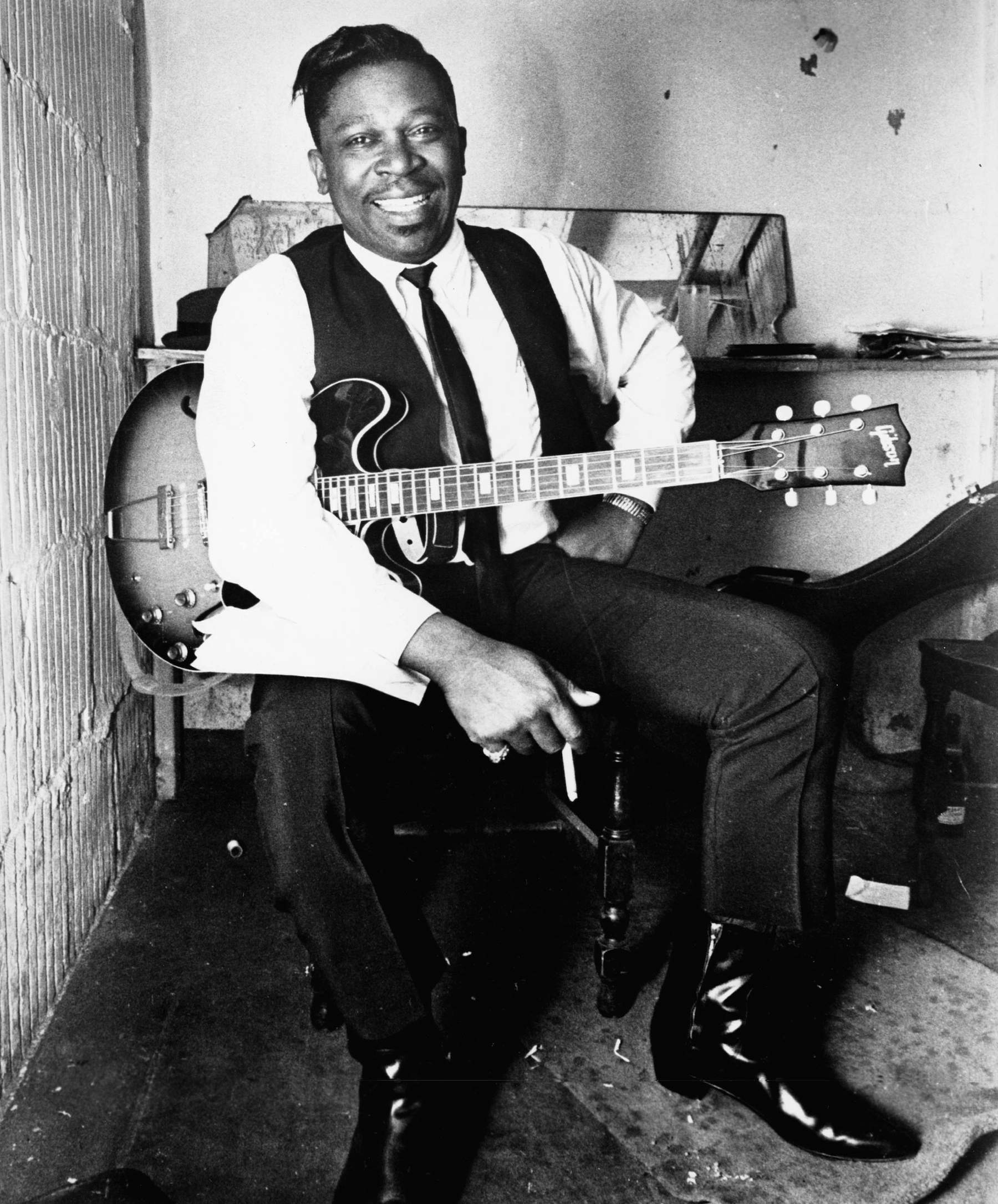

Another popular misconception is that Bukka helped B.B. get a foothold in the Memphis blues scene on his first visit to the city. “No, he helped me get a job,” B.B. explains. “I worked for a company called the Newberry Equipment Company. That’s where Bukka was working, so he helped me get a job. I stayed there a long time.” It was, however, apparently Bukka who inspired B.B.’s sartorial elegance, telling the young musician something along the lines of “When you play the blues, always dress like you’re going to the bank to borrow money.”

Eventually, the misunderstanding over the broken tractor exhaust was settled, via a polite letter courtesy of B.B. and either $600 or $800 – the exact figure escapes him – and he returned home to his wife and job. He wasn’t back for long, however, before the lure of Memphis proved too strong to resist. This time, though, he was determined to make his way, and money, as a musician.

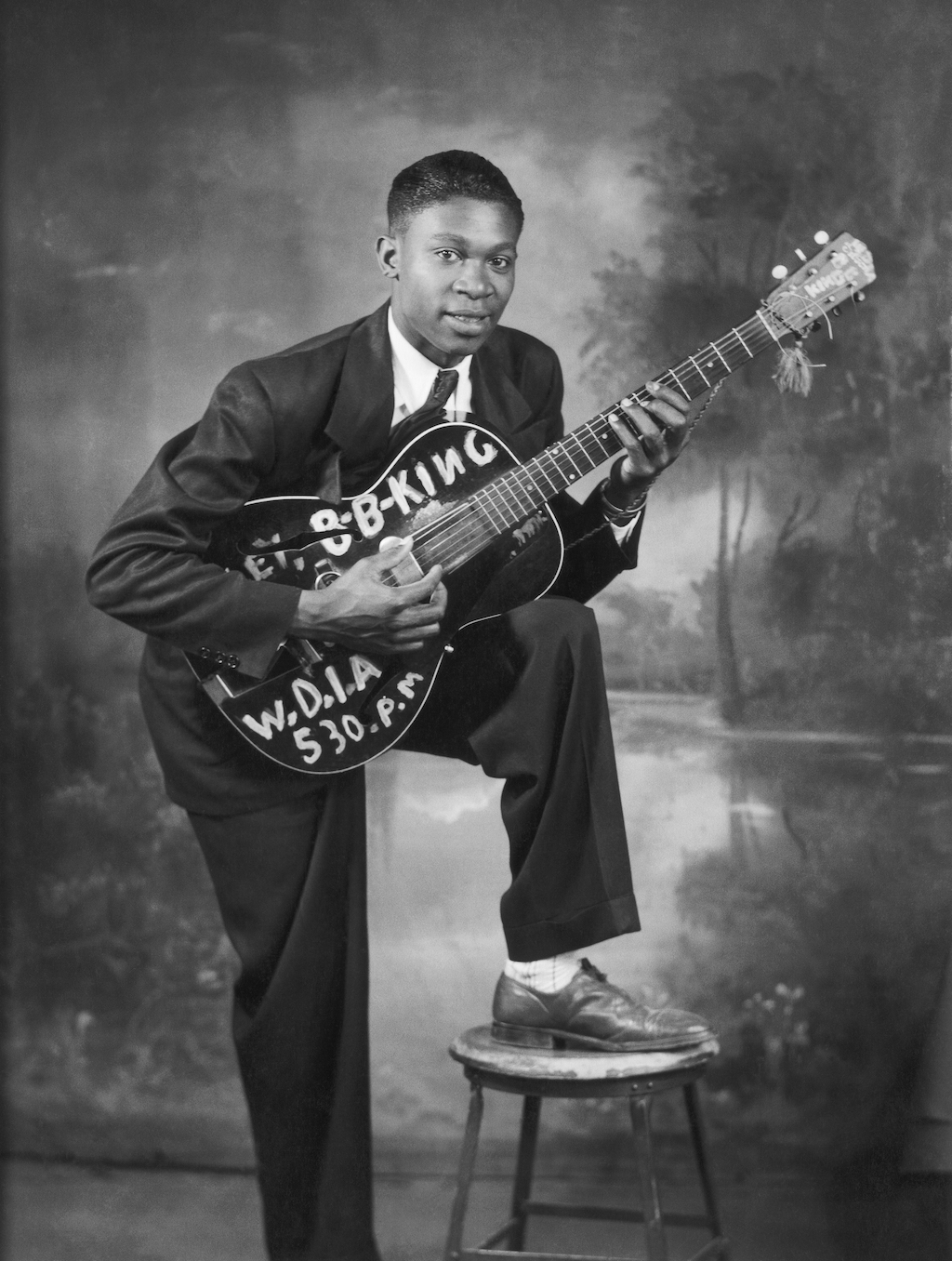

B.B. found a job on Memphis radio station WDIA – which was the first to be programmed entirely by African-Americans – on Union Avenue.

“I don’t know why, but all of the radio stations east of the Mississippi river started with a W,” says B.B., shaking his head. “All of them west of the Mississippi started with a K, I think. I never knew why it was like that but that’s the way it was.”

Speaking of initials, it was while working at the station that young Riley B. King first picked up his ‘Beale Street Blues Boy’ nickname – a reference to the local blues landmark, where he now owns a nightclub. The nickname was later shortened to ‘Blues Boy’, then ‘Bee Bee’ (as seen painted on his guitar amplifier in a photo from the time), before he settled on the now legendary B.B.

It wasn’t long until B.B. decided he wanted to make a record. “I got in touch with a group out of Nashville,” he recalls. “The record company was called Bullet. So, I talked with them, and had my boss out at the radio station talk with them, and they agreed to record me.”

B.B. recorded four sides at the WDIA station in May or June 1949, for release on the Bullet label: Miss Martha King, When Your Baby Packs Up And Goes, Got the Blues and Take A Swing with Me. All four tracks were recorded with pianist Phineas Newborn, Jr, guitarist Calvin Newborn, tenor saxophonist Ben Branch, trumpet player Thomas Branch, Sammy Jett on trombone, the brilliantly-named Tuff Green on bass and drummer Phineas Newborn, Sr.

The band were all top-notch cats. Sadly, B.B.’s self-penned tracks were way beneath them, with the man himself admitting they weren’t up to scratch. But as he says, “you can hear what I was trying to get to.”

B.B. soon found himself being pursued by the Bihari Brothers, the owners of Modern Records. “They found me,” says King. “I was still at the radio station. I stayed at the radio station long after I was sort of popular. Long after. They found me because of Ike Turner. He knew the Bihari Brothers and he sort of worked as a scout for them at the time and he knew me… And I knew him.”

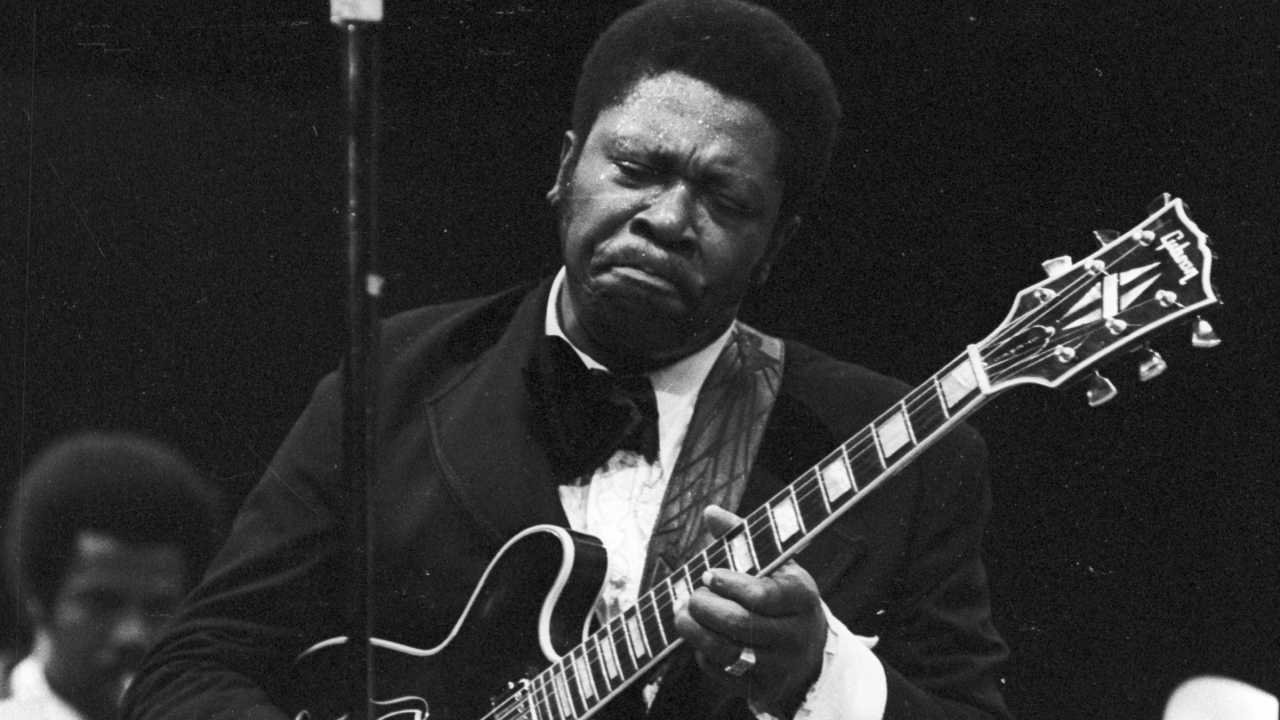

Now, this might be teaching your granny to suck eggs but we should mention that B.B. King calls whatever Gibson ES-355 semi-acoustic guitar he happens to be using at any given time, Lucille. The reason he does that is the stuff of blues lore… and if you don’t know the story, you should.

Towards the end of 1949, B.B. is playing a date at a dance hall in Twist, Arkansas. It’s a cold night so, in seemingly typical Arkansas fashion, the hall is being heated by a barrel part-filled with kerosene that has been lit, a fairly common practice at the time. While B.B. and his band are performing onstage, a fight breaks out between two guys nursing some type of beef. Of course, during the scuffle the blokes knock over the barrel of kerosene. The burning fuel spills out and the building is soon aflame.

B.B., along with anyone else with any sense, runs out of the building then remembers that he’s left his Gibson guitar on the stage. He runs back into the hall and grabs his guitar. The next day, King discovers that not only did two people perish in the fire, but the two men who were fighting were fighting for the honour, or otherwise, of a woman called Lucille. King christened the guitar he rescued Lucille, and every one he’s owned since, to remind him never to act so stupid again.

The Bihari Brothers set up some recording time with producer Sam Phillips at his Memphis Recording and Sound Service at 706 Union Avenue – the place that would soon become better known as Sun Studio, the home of Elvis Presley, Johnny Cash and Carl Perkins, and the original sound of rockabilly.

B.B. cut some sides at the studio – including B.B. Boogie – until the relationship between the Bihari Brothers and Sam Phillips soured. B.B. had his own bone to pick with Phillips: “He said something – and I’m quite touchy – he said Howlin’ Wolf was the best blues singer that he had ever recorded. I had been over there too, so I figured he didn’t give a damn about me.” [Phillips, to his credit, maintained his belief that Howlin’ Wolf was the greatest ever, right up until his death in 2003.]

As it happens, B.B.’s first breakthrough hit was in the post. Recorded in the Memphis YMCA in September 1951, _Three O’Clock Blues _was a song that B.B. had been practicing for some time: “I had heard _Three O’Clock Blues _from Lowell Fulson. I got to where I could sing it good, so the Bihari Brothers let me cut it and it was a hit. But what they did – they copyrighted the song as if I had wrote it, but I didn’t. So, it was a big selling record for me. I started then to begin writing songs myself.”

B.B.’s first bonafide classic the song made an impact on listeners way beyond the airwaves around Memphis.

“I first heard B.B. King on Three O’Clock Blues,” remembers Blues Breaker boss John Mayall. “I came out of the army in 1955, and up to that point I hadn’t heard him; or heard of him pretty much. Somebody that lived down the road, a West Indian, happened to have a 78 of B.B.’s record. I was just amazed at his high singing voice. That was the first thing that struck me; and just the way he was playing. It was something very different.”

For Eric Clapton, B.B. found his groove while working with the Bihari Brothers in the 1950s:

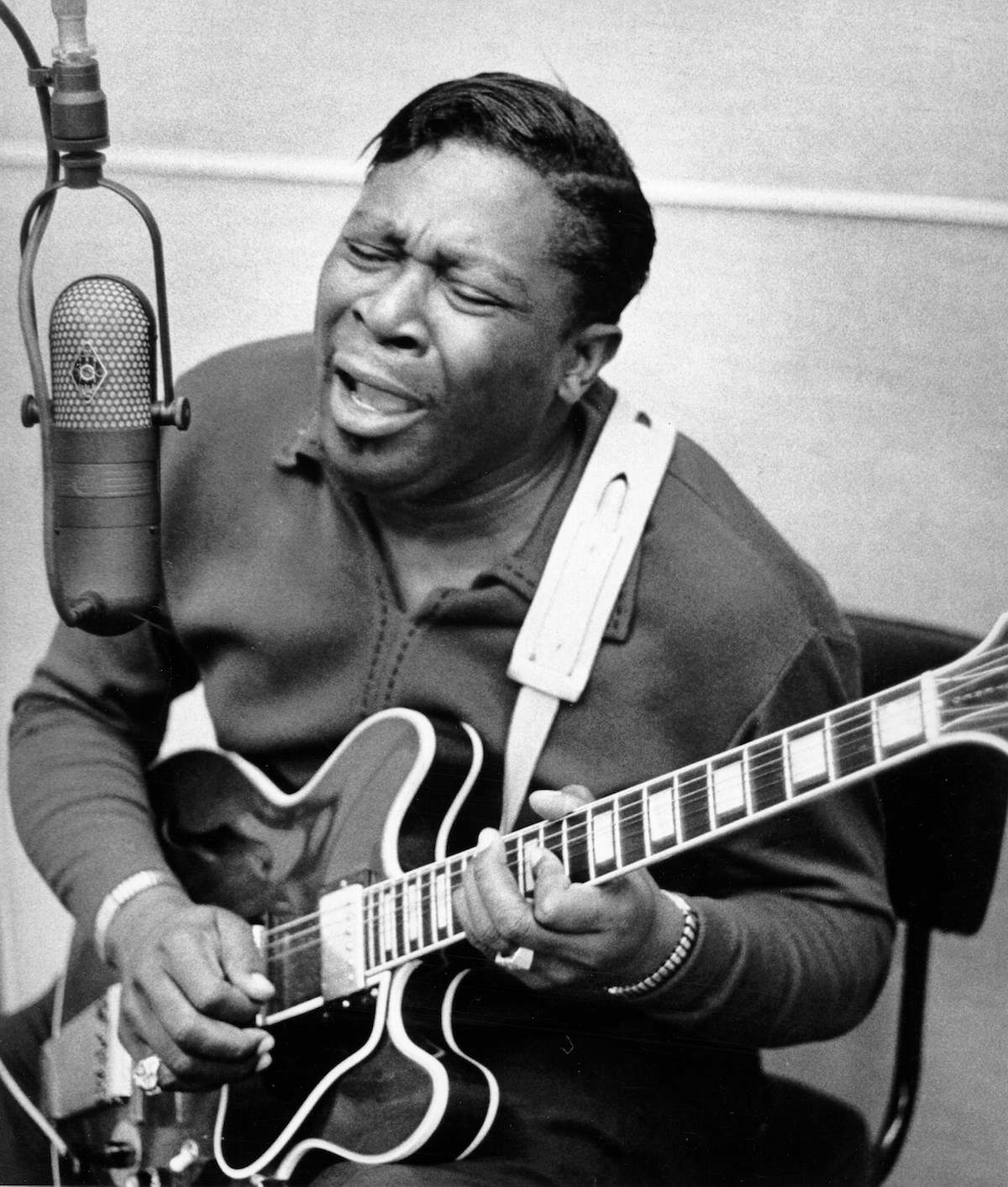

“I think he found his voice early on with the guitar,” says Clapton. “If anything, it’s really just become more refined. He doesn’t have to play as much, as he did in the old days. He found a way to condense it. When I first heard him it would have been Sweet 16 Part 1 & 2 (recorded in Los Angeles in 1959). It’s a mono recording, and he’s obviously playing live with a big orchestra.

“I immediately recognised that he was playing guitar like he sings. His voice is answering the guitar. No other blues guitar player can do that in the same way. B.B. sings with his guitar.”

The relationship between B.B. and the Bihari Brothers ended when he jumped ship to ABC. The reason? The oldest one in the book: money. “I have a friend named Fats Domino,” says B.B. “He was on ABC and, at that time, it looked like everything he touched was a hit record. That’s when he told me I was with the wrong people.”

B.B. lost a certain amount of artistic freedom when he split from the Bihari Brothers, but his association with ABC gave him financial stability and lead to him recording one of the greatest blues records of all time, Live At The Regal. This is the record that drove a bunch of tone hungry English kids crazy in 60s London – and this is the point in the feature where B.B’s famous fans take over the narration to discuss his influence, legacy and genius.

“There was a now-defunct blues record shop in Lisle Street in Soho, near the old Flamingo Club,” recalls former Rolling Stones guitarist Mick Taylor. “All the guitarists used to go there on a Saturday morning – Jeff Beck, Eric Clapton, loads of people. They used to import American blues albums and singles. One of the first albums I ever bought was Live At The Regal, recorded at a famous theatre in Chicago. That was very influential… And an album that’s dear to my heart. That’s B.B. King in his prime.”

B.B.’s 1965 Live At The Regal is a career-defining record in much the same way as his later anthem, The Thrill Is Gone. The album is an example of ‘as good as it gets’, thanks to a dynamite performance from B.B. and his band, captured at the Regal Theater on the South Side of Chicago on November 21, 1964. Aside from B.B., the line-up features top-line dudes: Duke Jethro on piano, Kenny Sands on trumpet Johnny Board, Bobby Forte (both tenor sax), bassist Leo Lauchie and drummer Sonny Freeman. B.B. works the crowd like a pro, pulling screams of ecstasy from the women and howls and hollers from the men.

Curiously, the only person that doesn’t get the album’s significance is B.B. himself. “I think it’s a good album, yes,” he says, calmly. “But it wasn’t like some people have said, that it was the best thing I’d ever done.”

But for guitarists like Mick Taylor, Live At The Regal is a masterclass in using the guitar as an extension of the voice. “I thought about it a lot back in the days when I was still learning about blues playing,” says Taylor. “Learning the art of singing and answering what you were singing with a guitar phrase… I think that’s where B.B. King is a master. He has a great voice, and a great sense of dynamics. He could bring a song right down, and of course his band would follow him. Unlike Albert King’s band; if they missed a beat or were too loud, Albert would turn round and give them the evil eye… a nasty look. I’ve never seen B.B. King do that.”

“Live At The Regal was like this pivotal musical watershed that took me away from the British Blues – temporarily,” says Joe Bonamassa. “I had just discovered American blues for the very first time, after listening to the English stuff like Clapton, Peter Green, Paul Kossoff and Free, and every incarnation of John Mayall and the Blues Breakers. Live At The Regal was the first American blues album I really liked. It was lively, and big, and had horns.”

“B.B. King has been a huge influence on me,” says Free and Bad Company vocalist Paul Rodgers. “When I first met Paul Kossoff and he asked if he could get up and jam with me at The Fickle Pickle in Finsbury Park all those many years ago, the first things we played were B.B. King songs like Every Day I Have The Blues, off Live at the Regal. Paul introduced me to that record and we really sat and listened to it. One of the things that B.B. has is a great rapport with the audience.”

If B.B. was unaware of the effect his records were having on American kids in the late 60s, there’s no way he could have guessed the influence he was exerting over in London. Blues Breakers leader John Mayall had no trouble spotting which of his Holy Trinity of guitarists were feeling B.B.’s style the most.

“Of the three main guitar players from the English stable – Eric, Peter Green and Mick Taylor – I would say that Eric was most influenced by Freddie King; Mick Taylor was most influenced by Albert King; and Peter Green was most definitely a B.B. King devotee. He learned how to play as little as possible, and most effectively as possible, in the same way that B.B. can play one note and you know exactly who it is. So, that was Peter’s goal. I think he learned a great deal from B.B.”

“That’s dead right to me… Very observant,” says Eric Clapton.

Mick Taylor, however, is not so sure. “Well, John is entitled to his opinion,” he says. “But I actually think Eric was influenced by Freddie and B.B King. B.B. especially.

B.B. has his own opinion on the subject. “I think Eric liked me as a guitarist – he’s a good friend,” he says. “But I don’t think he idolised me like he did with Albert King and Buddy Guy.”

“There’s simplicity and honesty in B.B’s playing,” continues Mayall. “What he can do with one note a lot of lesser guitar players would not be able to accomplish playing a million notes a minute. He’s been a great influence on a lot of people I know who have latched onto the fact that it’s not how many notes you play, it is how you play them in order to convey your feelings.”

The old ‘one note’ thing doesn’t half get on some guitar players’ goats, but if there is a blues player that is recognisable from a single pluck, it has to be B.B. King.

“Yeah, one note is all it takes for B.B.” says Eric Clapton. “Often that’s exactly what he’ll do. He’ll slide up to hit the octave to make a point. It’s like an exclamation mark. He’ll sing a phrase, and to punctuate it and give it drama he’ll slide up and hit that octave with just the right amount of vibrato. It’s about economy and power, with the maximum amount of passion.”

“I’d say that’s true, yeah,” agrees Mick Taylor. “His sound is completely unique to him. One or two notes and I know it’s B.B. Certainly no more than three! I think his vibrato sets him apart. Eric’s playing and B.B. King’s playing is similar in that in the sense that they have the same kind of vibrato.”

Eric Clapton remembers the first time he played with B.B. Well, a reasonable chunk of it.

“It was during a period when I had become friends with Al Kooper,” he says. “He’d formed this band called Blood, Sweat and Tears, and their debut gig was at the Cafe Au Go-Go [in New York’s Greenwich Village]. So, I’d gone down with Al to see them play. I don’t remember how the jam with B.B. came about, but there we were, and I’ve seen pictures of us sitting on our amplifiers playing together.

“What I do remember – and it’s sad for the guy – the bass player with Blood, Sweat and Tears – a guy called Jim Fielding I think – managed to stay four bars ahead of everybody, you know, for about half an hour. I thought it was quite an achievement in itself. When you get to the end of a 12-bar sequence, someone will shout and everyone will fall back into the sequence. Well, this guy managed to remain out of sync the whole time.”

“I was 17,” says Texan slide guitar genius Johnny Winter. “It was a club in Belmont, Texas called The Raven. I heard it on the radio that B.B. King was gonna be there. So, I gotta hear this!

I had a fake I.D. and got in.”

Johnny was a fan but he wasn’t there just to listen to his idol play. “Yeah, I bothered him,” he laughs.

“I wanted to see him, but I really wanted him to hear me. I kept sending my band members up to ask him if it was alright if I played.”

What Johnny and his friends didn’t realise is that B.B. was eyeing them with suspicion. “We were the only white people in the club, and he’d been having tax problems,” laughs Johnny. “He thought we were from the IRS! He finally let me play and I got a standing ovation.”

B.B. chuckles at the memory; he remembers the encounter well. Not only the fear of undercover tax men, but his first taste of the young guitarist’s playing: “Johnny was good,” he says.

Not only did Johnny and his mates put the wind up poor old B.B., he also forgot to bring any gear with him.

“Yeah, I didn’t bring my guitar,” continues Johnny. “So I played Lucille!”

Johnny admits that B.B. went out of his way to accomodate him. “It was very nice of him to let me play cos he didn’t know whether I could play or not,” he says. I remember he kept saying, ‘We have arrangements’. I said, ‘I’ve heard all your records.

I know all your arrangements.’

“B.B. asked to see my union card. He wanted to check me out. It took him a long time before he decided to let me play. I think he was so glad that we weren’t coming to bust him for his taxes; he didn’t care if I could play or not (laughs).

“I met B.B. King on May 24, 1990,” says Joe Bonamassa. “I’d just turned 13. I was playing shows in upstate New York. When you’re that young and you play blues music you tend to get a lot of media. Especially how I looked – I was like this pudgy white kid with a Telecaster. I was attracting a decent crowd. Mainly curiosity seekers at that point – when I showed up to these gigs it was kind of like a circus. This one promoter rang my mother one time and booked me to open up for B.B. King, which was a thrill because about three years before that I had discovered Live At The Regal. To meet him that first time was extraordinarily special for me, because he was one of my musical heroes. When you’re that young and able to meet someone like that, it was really a special thrill. I just thought I’d play the show and then move on, but he ended up calling me back to his dressing room and we had a really lovely chat and I got to sit in with him that night. It was my big break and it totally changed my life. He plucked me out of obscurity. I’ve played shows with B.B. King pretty much every year for the past 22 years.”

When B.B. King passes on, sad as it will be, we’ll wager that he’ll be performing onstage, lounging around in his tour bus, or trundling somewhere between the two. While he’s not running at the speed he was when he played 342 shows in one year back in 1956, the man is 86 years of age and still tours his ass off. Like his contemporaries Chuck Berry and Jerry Lewis, the desire to hit the road is undiminished in B.B., regardless of age and ill-health [in his case, King has suffered from Type II diabetes]. He’s never happier than when he’s pulling into a new town and playing shows, spending hours chatting to fans and signing autographs.

While not many of the characters interviewed for this feature – and Jon Brewer’s brilliant film, The Life Of Riley – would expect B.B. to continue touring the world for much longer, all believe he’ll keep up his commitments in North America. For his part Eric Clapton is adamant that B.B. will never really put Lucille back in her case for good, unless he really has to. As Slowhand says: “It’s his life. It’s what he does.”

“He’s a trooper!” shouts Paul Rodgers. “He’s played almost every night of the week for years and years. I think he just takes Christmas day off or something ridiculous like that… amazing guy.”

Others that you would consider consumate road warriors are still blown away by B.B.’s relentless schedule. “I do about 120 gigs a year,” says Johnny Winter. “B.B. used to play almost every night when he was younger. He played like 350 gigs a year. I don’t know anybody that could play as much as he did. Playing keeps you young.”

When we ask the man himself if he’ll ever stop rolling down the highway he looks us in the eye and replies with a simple “No.”

Ask him how he’d like to be remembered and B.B. takes a little more time to reach for an answer.

“‘He was a pretty nice guy’,” he says eventually with a grin.

“No… something like, ‘He was a son of a bitch but he was himself!”

This was first published in Blues issue 2.