To many scholars of Western music, the work of Steve Hackett’s composer idol Johann Sebastian Bach remains unsurpassed. His acute sense of melody, counterpoint and orchestration have cast a long shadow over all that has followed in the two and a half centuries since his death. In the younger, secular and infinitely sexier universe of rock music, there are certain works that succeed on their own terms so completely that they too are considered the zenith of their form. Albums such as Foxtrot, Selling England By The Pound and The Lamb Lies Down On Broadway by Genesis are held as iconic touchstones of the prog rock movement.

As a guitarist and composer, Hackett made a significant contribution to these revered artefacts, and his sophisticated approach to his instrument has influenced most guitar players with a taste for prog. In the 32 years since he left Genesis he has forged a rich, varied career during which he has toured constantly and dug deep into rock, fusion, pop and – more convincingly than most rock artists – classical music. As he sits down with Prog he’s amenable to ‘wearing his curator’s hat’ and talking about his Genesis days, but is also genuinely excited about his new album. Out Of The Tunnel’s Mouth is all the more tantalising for its guest performances by Yes bassist Chris Squire and the man Hackett replaced in Genesis in 1971, Anthony Phillips.

“He is Mister 12-string, I wouldn’t even pick one up in his presence,” smiles Hackett, no slouch on the instrument himself. “I met Ant over the years at the odd wedding or christening, and we always said we would’ve got on well if we’d both been in Genesis at the same time – we wouldn’t have got in each other’s way. I’ve been trying to talk him into doing something on the album for some time, and I think the combination is beautiful.”

Phillips’ contribution adorns the plaintive chorus of Emerald And Ash, a sweeping song themed on truth, illusion and deception. Out Of The Tunnel’s Mouth is populated by such widescreen soundscapes, adorned by sublime guitar and infused with classical and Eastern flavours too. Amazingly for a work of such scale it was recorded in Hackett’s living room, and brought together in a virtual studio there by writing partner, keyboardist and producer Roger King.

“Roger loves Bach, like me. There are some things we wrote together but in the main I’d start off with a glimmer of an idea and he’d run with it. He’d spend time getting it right, mixing different instruments, cannibalising performances. The whole thing was constantly being remodelled, there’s hundreds of people on it but all recorded at separate times. It’s all in the details, and Roger is so brilliant at that. It sounds enormous.”

In parts Fire On The Moon sounds more like it was recorded on a collapsing star rather than a lounge. Its soft, jewellery box verse giving way to some soaring soloing from Hackett, and a massive primal chorus held down by the bass work of Chris Squire.

“I met Chris Squire back in the 80s when I was working with Steve Howe in GTR. Of course I’ve always adored his work – what guitarist wouldn’t – and we’ve got closer over time, I even played on his album of Christmas carols [2007’s Chris Squire’s Swiss Choir]. He’s a bit like me in the studio, living room I should say. He gets more enthusiastic as he works, and I think, is it really something I’ve written that’s getting him so excited?! He refines and refines, finds the melodic line around things. He’s unique amongst bass players, and he even got me into the Led Zeppelin re-formation at the O2. I wanted to go but there was a problem with my passes. Chris was playing with Keith Emerson at the concert, and I carried his Rickenbacker in pretending to be his roadie!”

The darker side of the song comes from its inspiration, the traumatic dissolution of Hackett’s 32-year marriage to Brazilian artist Kim Poor, who created some of his most striking album art over the years.

“I was going through a very difficult time in my life, aware that I’d really come to the end of the road with Kim. I’m a great one for picking up books and gleaning titles that way, but sometimes it’s easier to look everywhere except inside yourself. I went through several nervous breakdowns with this thing; it really felt like the ground giving way beneath my feet. I thought, I’m gonna stick this in a song, and whether people say it’s the most bloody depressing thing ever or some might feel it’s got some kind of resonance. So if anyone gets any consolation, great. It’s very honest.”

Elsewhere there is the intense fusion-like guitar in Tubehead, the flamenco-flavoured Nomads is dedicated to the gypsy life and Sleepers vividly evokes a surrealist dreamworld while the Southern tones of Still Waters sounds like a freshly unearthed blues cover, performed by angels with lightning-charged guitars.

Looking at his overall catalogue, the album sits in a sunnier place than his gothic 1999 concept piece Darktown, and in many ways picks up where his overlooked work To Watch The Storms left off in 2003. Hackett’s classical influence looms large and there’s also a strong sense of his taste for world music, so prevalent on 1984’s Till We Have Faces. The spicy closing track Last Train To Istanbul features his flautist brother and long-time collaborator John, and was inspired by Turkish music Hackett heard in Sarajevo.

“We did get involved with this motif of trains,” he says. “We were going to use that song as the title track to the album, but as the artists on it live all across the world it wouldn’t have been practical for the tour. It did give us our tour title though, ‘Train On The Road’.”

As he sets off on European tour, his set comprises tracks from the new album but he also has a wealth of music to draw upon, from his impressive catalogue and of course some major Genesis numbers too. He’s been known to play Blood On The Rooftops from his last album with the band Wind And Wuthering, the showcase Firth Of Fifth from Selling England By The Pound, and of course Horizons, his solo, Bach-inspired signature piece from Foxtrot.

“When I joined Genesis, Peter [Gabriel] said to me, we want you to write. I was immediately made a full writing partner and I’d barely written a whole song by then. The reason was they considered the arrangement to be as important as the tune, and in that way it was a classical approach. It was intimidating, daunting, thrilling, because they were gifted songwriters by that time and I was still cutting my teeth. I still don’t think Genesis really understood the difference between a verse and a chorus. And that was a strength, no-one was working to a formula. We were interested in switching between Scottish plainsong, fusion, Vaughan- Williams moments, to hymnals. And then those brilliant rhythmic changes…”

For all that band’s subsequent success, some of Hackett’s fondest memories of Genesis were formed in 1973, while touring Selling England… in the US.

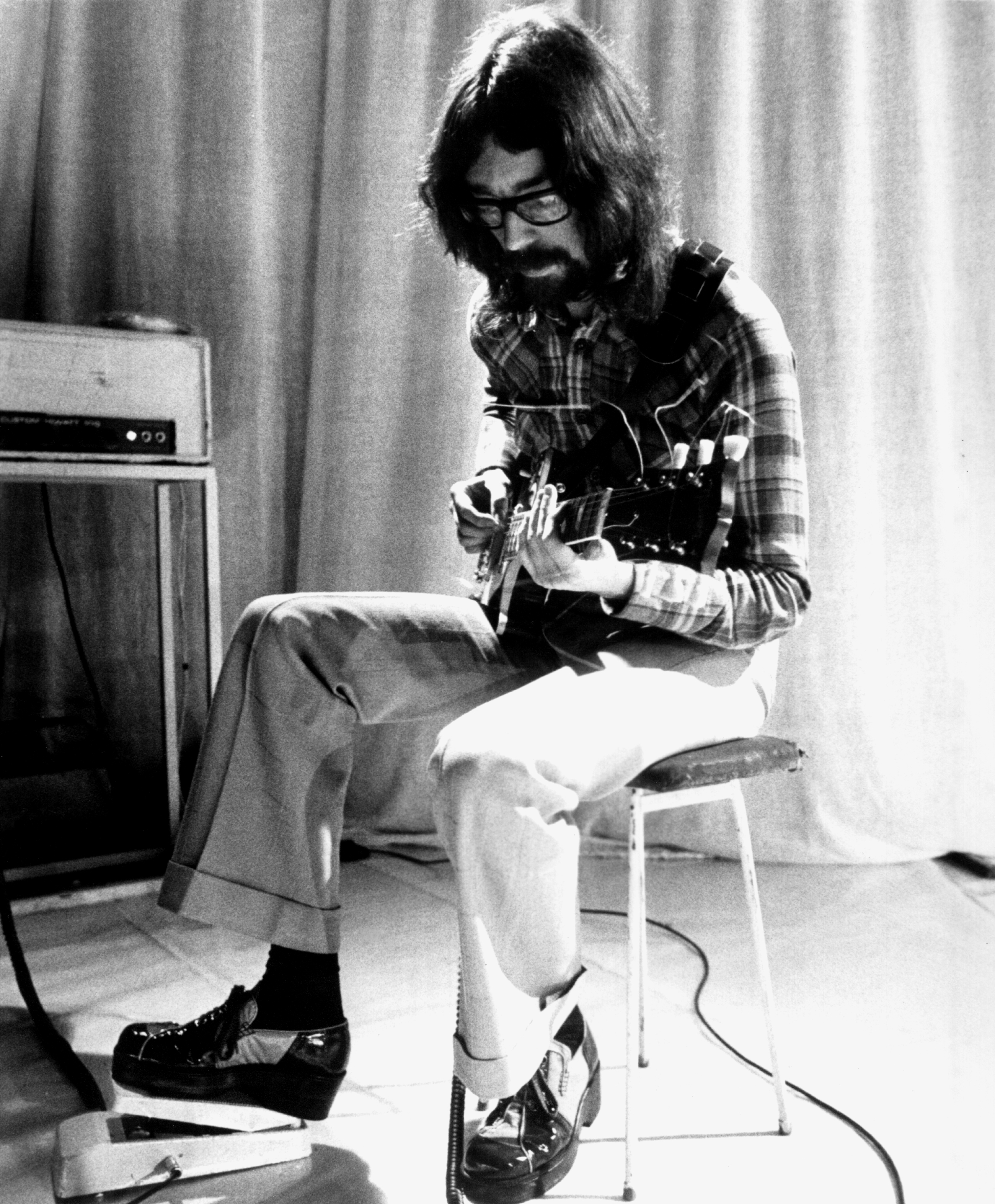

“We played The Roxy in LA in December, two shows a night. I remember thinking, I’m in the hottest band in the world. We were playing stuff like Watcher Of The Skies, Dancing With The Moonlit Knight and we sounded great. I was in love with the band. I felt more at home onstage than I did at home back then. I played sitting down on a stool, hair down to my knees, beard, glasses – I could’ve been anyone.”

Four years later he left, frustrated by how few of his song ideas were being adopted for use on their albums. He already had one solo release under his belt, 1975’s Voyage Of The Acolyte, recorded with contributions from then-band mates Phil Collins and Mike Rutherford. The follow-up Please Don’t Touch was a top 40 hit in 1978. It remains pleasingly eclectic, veering from the fusion of Racing In A via the romantic classical tones of Kim, through to Richie Haven’s lovely folk reading How Can I? and the ballad Hoping Love Will Last, featuring a soulful vocal from Randy Crawford.

“Since Please Don’t Touch I’ve had this approach of trying to cram rock albums with as many disparate styles as possible. I always wanted each album to be a complete journey through music, to make that a calling card. I was both condemned and praised for it; Tony Stratton-Smith who signed me to Charisma Records said it’s both a strength and weakness.”

While it was just as diverse, 1979’s Spectral Mornings was recorded by one permanent band, including his brother John, keyboardist Nick Magnus and vocalist Peter Hicks. It’s more coherent, and is often voted his best album by fans.

“I think it’s because I was in a band with its own identity. I look back on that with the most affection, because I remember the band was on a high, having done a tour where they were forced to play songs from …Acolyte and Please Don’t Touch, and on Spectral Mornings there were songs designed for live performance, like Clocks, and a lot of the others fell into place. Sometimes I wish I could write another tune like Every Day, but I fail every time. I was also very pleased with The Virgin And The Gypsy, which was a lot more laidback. I came back from the canteen and everyone had added these wonderful parts.

“It’s always a good idea to take a risk with a song, because if you’re not sure it’s going to work out then those ideas aren’t clichéd, you’re taking a chance, and with a willing team and a patient engineer the sky’s the limit.”

Taking that chance paid off. Hackett poured himself into touring and opened the 1980s with his biggest solo success to date, the Top 10 album Defector.

“I was doing a lot of gigs at that time, it’s as simple as that. We were touring the UK, Europe and the US, and fans responded warmly to the characters that were in the band. Also I was starting to head more towards co-writes, and I do a lot of that now. When I first left Genesis people were saying I should be working with a Phil [Collins], a Bill Bruford, a Peter Gabriel, but once they saw what my guys could do on record they got it. It’s hard to follow the legacy of the guys I worked with, they were so obviously brilliant. But a young band has to be given a chance.”

As, perhaps, does your average supergroup. Six years later, Yes manager Brian Lane brokered the formation of GTR, a ‘dream pairing’ of Hackett and fellow uber-guitarist, Yes’s Steve Howe. By certain measurements, GTR worked. Released on Arista in 1986, their self-titled album was a commercial triumph in the US, where it grazed the Top 10, and it led to a lucrative tour and garnered them a Top 20 single, When The Heart Rules The Mind. But for Hackett at least the success was a sour one. His lukewarm take on the enterprise is well documented, with the whole affair having, to him at least, an air of corporate bloat about it that chimed with those Wall Street times.

“I thought When The Heart Rules The Mind was a great song. We wrote that on day one, Steve had a guitar riff, I had a lyrical idea, we put the two together and boom, a hit single. But we were operating in an era when corporate rock was king, and to fund the project I felt we toed the party line more than we needed, and the band might’ve had more longevity had we gone our own sweet way and dictated our own terms. But [legendary Arista CEO] Clive Davis and Brian Lane were very persuasive. If we’d formed now we’d write in a different way. We’re in a time of home-grown recording where the process is much more organic, and it’d be easier to come up with a band identity that wasn’t required to be instantly wonderful.

“A band of unknowns is allowed to develop over time, whereas GTR fell into the same thing as say, Blind Faith. We all thought it would be Winwood at his best, Clapton at his most fiery, but how could it possibly live up to the expectation? There were flashes of that in GTR, but I think it’s this idea of going with sure-fire bets rather than taking a chance and see where it leads. We were answerable to our sponsors from the get-go, and we had a band on the payroll. You’ve got to cover those wages somehow, and we were spending immense amounts of money in Townhouse Studios. I had a bankrupt company in England and a hit album in America, but that’s how it defined itself, by its extremes.”

He would attempt the supergroup route 10 years later with John Wetton, Ian McDonald and Chester Thompson. but in 1988 he lurched to the other extreme of his musical personality with Momentum, a palate-cleansing collection of solo classical guitar pieces. Vindicating his belief in the power of such pared-back music, his solo tour of Europe that spring took him to the former Soviet Union, where he played self-penned pieces and also selections by his beloved Bach to receptive audiences that at one point reputedly numbered 90,000 people.

Across his career Hackett has tempered his heavier, progressive output with forays into the classical arena. Some have been spare recordings such as his 1983 release Bay Of Kings, the beautifully judged Sketches Of Satie and last year’s Tribute, dedicated to music popularised by his classical guitar hero, Andrés Segovia. Other albums have been high-production, high-concept works: his setting of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, recorded with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, and Metamorpheus, which saw him take on the myth of that lyre-wielding interloper, Orpheus. To the onlooker he may seem to straddle two disparate musical worlds, but to Steve Hackett – whose own influences range from Bach and Segovia to Hank Marvin and Jeff Beck – there is no disconnect between them.

“There are many musicians who operate in another area, say heavy metal, and at home they’re listening to Mozart. It’s good to keep your ears open. I listen to a lot of jazz too. I don’t always like it but I listen to it, because I want to know what jazz’ll give me that I won’t get from Bach. Take Led Zeppelin for instance. Many fans of progressive music would say their favourite Led Zeppelin song is Kashmir. And that’s great, it starts out minimalist, and then you’ve got to the moments where chords come crashing in, and that’s where Zep and Genesis join up, those chords define the lead line. But I suspect without casting an ear to classical music you’re unlikely to have enough chords in your armoury to use that influence. That knowledge is mighty, whether you’re playing power chords or trying something a little more symphonic.”

You know you’ve done something right when they name a weekend after you, and in March around 500 fans gathered from across Europe for The ‘Steve Hackett Event’, curated in the town of Remscheid-Lennep by the German Genesis fan club. This two-day celebration of the guitarist’s 40-year career culminated in an acoustic performance and Q&A session, during which he fielded familiar queries about his hobbies, his guitar techniques and whether he did or didn’t play on rare Genesis tracks Pigeons and Match Of The Day. And of course that perennial question: will the Lamb-era line-up of the band ever re-form? Even today it elicits the perennial answer: “Never say never,” smiles Hackett.

And the train keeps a-rolling.

This article originally appeared in Prog #10.

Steve Hackett will be appearing at this year’s Stone Free Festival, get your tickets here.

For more on Steve Hackett, then click on the link below.