For the first five years of their topsy-turvy career, Thin Lizzy had been also-rans – strictly second div, with their 1973 novelty hit Whiskey In The Jar, their earnest ‘Irish rock’ concept albums and their constantly blurring line-ups. Could-have-beens. Maybes. Jokes.

They were saved by the bell of their sixth album, Jailbreak, in 1976. For the first time the band successfully showcased their intoxicating blend of rock-funk-folk-blues bloodletting, and overnight Lizzy went from uninvited guests to new leaders of the pack.

The big hit single from the album, The Boys Are Back In Town, had taken them from town halls to the big league: multiple nights at London’s Hammersmith Odeon, a first major tour of America, gold records on two continents. Cool cats adored by their kitties.

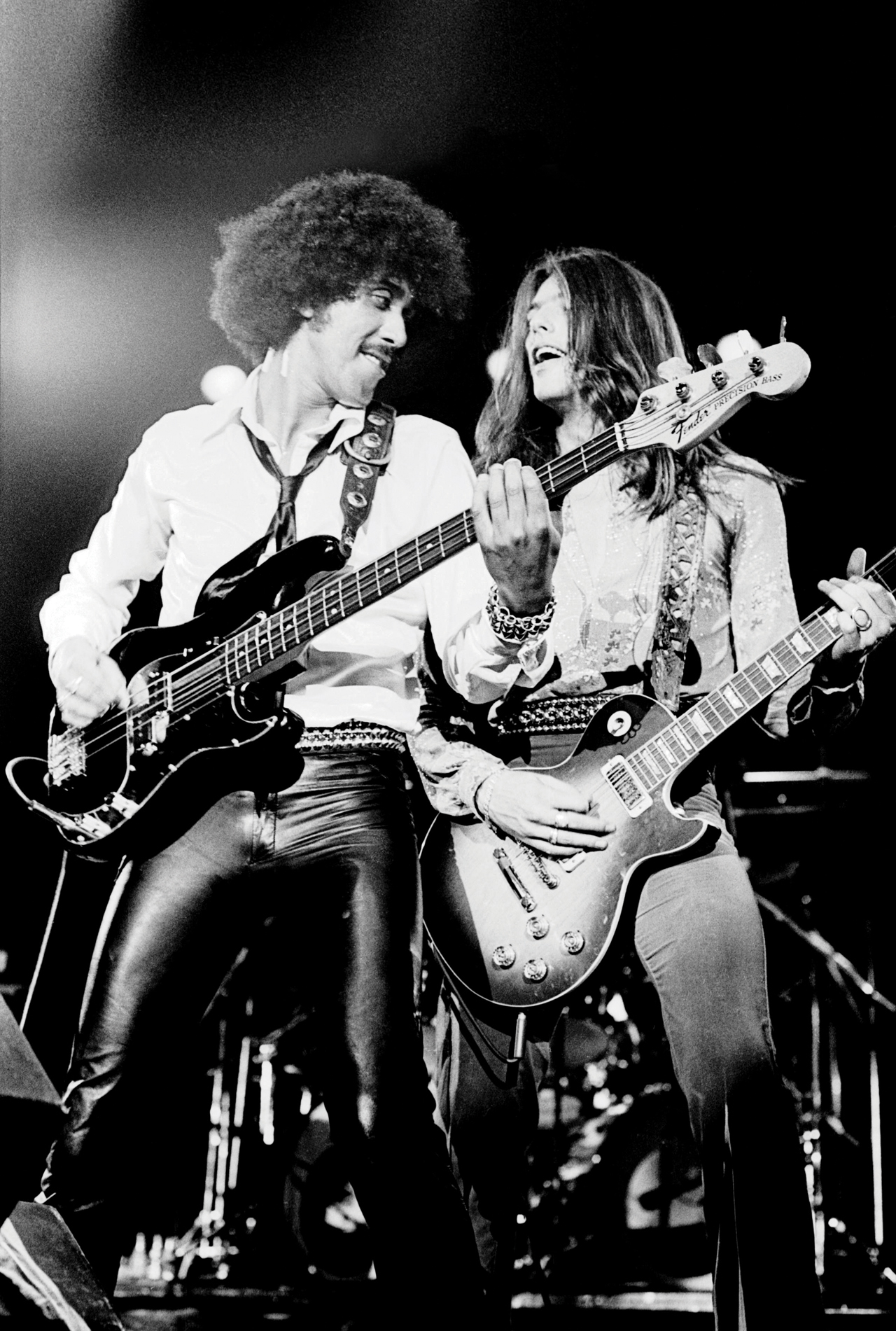

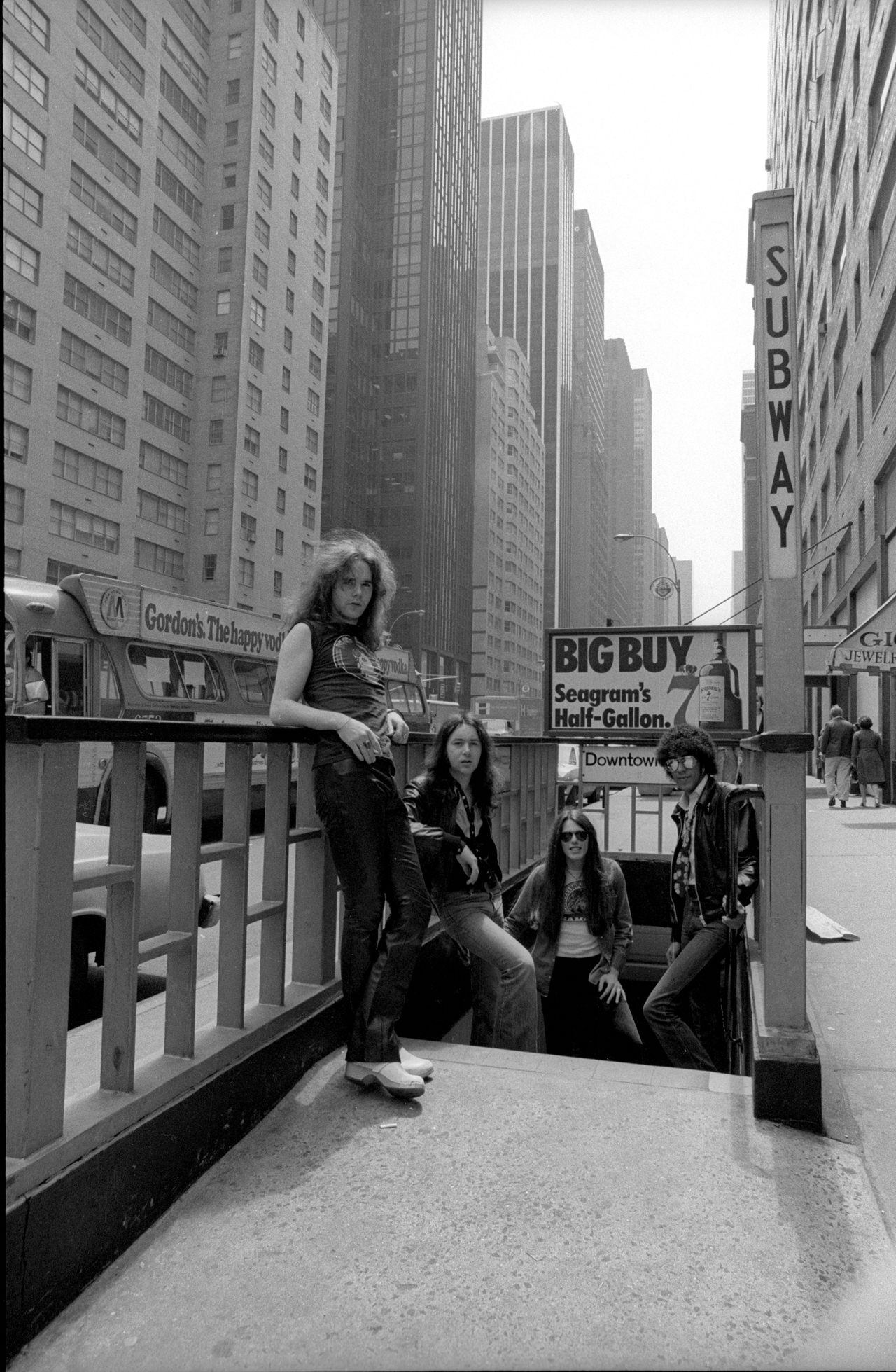

Twenty-six-year-old singer and bassist Phil Lynott was the star. Black Brazilian father, white Irish mother, Lynott combined the Stagolee swagger of Jimi Hendrix with the street poetics of Van Morrison.

Flanked by two genuine gunslingers in 20-year-old guitarist Brian ‘Robbo’ Robertson (Scottish, fiery, bad for good) and 25-year-old Scott ‘Good Looking’ Gorham (So-Cal cool, hair, chick magnet), in the blister-popping heatwave of the summer of ’76, nobody in rock carried more heat than Thin Lizzy.

Then, almost before the party got started: the crash. As drummer and co-founding member Brian Downey puts it now, speaking from his rural Irish abode: “It wasn’t helped by the lifestyles the band were living, but the timing couldn’t have been worse. People coming down with hepatitis and slashed hands… Situations that you could never predict would happen – but did happen.”

A prestigious US arena tour opening for Rainbow had been abandoned after Lynott – already deep into his potions and powders – had picked up hep C from a dirty needle. Fleeing home to London, Lynott wrote most of the songs for the band’s hastily scheduled next album from his hospital bed. The result, Johnny The Fox, had ‘follow‑up’ written all over it – emphasised by the fact its own hit single, Don’t Believe A Word, was an almost identikit Boys Are Back reshuffle.

In Britain, it didn’t matter. Lizzy had repeat hits and even more success on their winter ’76 tour, culminating in the sold-out three-night stint at the Hammersmith Odeon that would be recorded and later released as the 1978 Live & Dangerous double album. But after a brawl at the Speakeasy involving his tough-guy pal, singer Frankie Miller, Robbo slashed his left hand so badly he was told he’d never play again. Lizzy were forced to cancel their second US tour in a row – a month of dates in December intended to make up for the previous cancellation. Lynott was furious.

According to Gorham, “Phil had become obsessed by everything American and really saw the band making it big there.”

But with Johnny The Fox failing to follow Jailbreak into the US Top 30, and another tour in tatters, Lynott was convinced the band had blown their big chance. He was right.

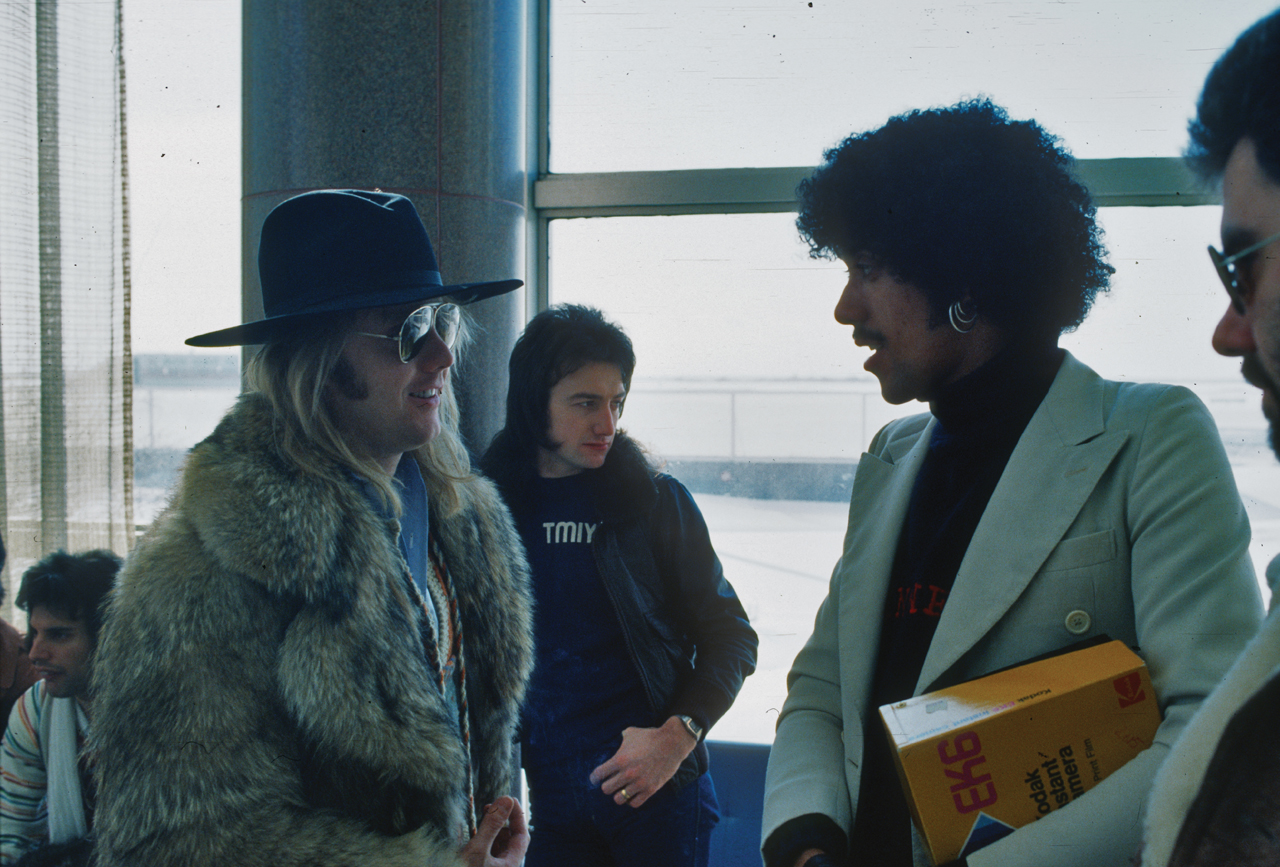

There had been a decent attempt to recover lost ground in America with the self-styled Queen-Lizzy tour of the US in the early months of 1977. “We really learned a lot from opening for Freddie and the boys,” says Brian Downey. “They were in a different league to us.”

The focus now, though, was on ensuring their next album would restore them to the US charts. They already had the title, Bad Reputation, which was a sardonic reflection on their damaged relationship with American concert promoters, record company executives and everyone else that had all but thrown in the towel when it came to trying to get the band off the ground in the States.

Cliff Bernstein, then the band’s A&R man at their US label Mercury – and later co-manager of Lizzy-wannabes Def Leppard – once said: “It broke my heart that Lizzy continually fucked-up in America. In the end you just move on to other things.”

In less than a year, they had gone from being compared favourably to Bruce Springsteen to completely dropping out of the conversation. Bad Reputation would be their belated attempt to fix that. “Promoters started wondering, ‘Thin Lizzy – they cancelled again?’” says Downey. “They were questioning the band’s credibility. After that, we had no chance of breaking America unless we had another massive hit.”

Belfast boy Gary Moore had stepped in to fill Robbo’s shoes for the Queen tour – but on a strictly temporary basis. Moore-o, as they knew him, had already joined the band and left once before. “He had very high aims as an instrumentalist,” Lynott would later tell me. “He was into jazz rock and very technical stuff.”

Having known Moore since they were teenagers in Ireland, however, Lynott also knew how badly the guitarist wanted to be a star. When Moore declined to continue replacing Robbo for the Bad Reputation sessions, Lynott was prepared to play a waiting game, and decided to record the album with just Gorham on guitar.

“Phil said: ‘Fuck it, we’ll just do the thing ourselves,’” Gorham said. “Lizzy had started as a three-piece – I guess he figured it would be no big deal. But I loved Robbo and I wasn’t at all sure about handling a whole album on my own.”

Robertson, meanwhile, put on a brave front. “I’m getting my own band together!” he bragged to anyone who would listen. But in truth he was devastated to find himself on the outside.

“Phil and I had our differences,” he said at the time, understating the case more than a little, “but we always worked well together.”

In truth, Lynott rarely ventured over to Robbo’s side of the stage, instead throwing his best shapes in tandem with Gorham, with whom he felt a much greater kinship. Phil and Robbo would fight – “Phil had hands like fucking shovels!” – and Robbo would invariably come off worse. Phil and Scott would hang out, going out to clubs, doing coke, smack, whatever; pulling chicks.

“Phil and I had this kind of clique thing going,” says Gorham. “Like our own language, little looks and things. That made it kind of tough sometimes when someone new came into the band. Like, you’re in the band now but you’re gonna have to prove yourself first before you get really in with us.

“A big reason why Phil and I became such good friends was because we trusted each other. No names, but maybe with some of the other guys, he never quite trusted them. We always tended to agree, musically. Not always on album but definitely on stage. Also, I’ve never been worried about being a big star, so that never came between us either, where maybe it did with some of the other [guitarists].”

Robbo fancied his chances as a frontman. Moore actually became a frontman. Lynott had a head start on both of them and was determined that Bad Reputation would help keep it that way. But it was the twinned harmonies of Robbo’s guitar interplay with Gorham that defined the Lizzy sound – Robbo’s beautifully telegraphed solos and intricate flourishes that finessed Lizzy’s badass hard rock into something more lyrical and enticing.

Lynott knew working without his firebrand guitarist was a risk. To plug the gap, Tony Visconti was hired to produce. Visconti was then at the peak of his 70s powers, having produced all 20 of T. Rex’s major hit singles and albums, before latterly working with David Bowie on some of his most influential recordings.

At the time it seemed like a coup for Lizzy to have someone of Visconti’s stature involved. (Bowie’s Visconti-produced Low album was No.2 in the UK at the time.) Speaking now, though, from his London home, Visconti says he saw it as a no-brainer. “I just loved The Boys Are Back In Town. For me, it was the best single of that summer. Then when I met Phil a few months later, he charmed me. He had such charisma. I jumped at the chance of working with them.”

At Visconti’s suggestion, they worked out of Toronto Studios in Canada through May and June 1977. The producer – privately disappointed not to have Robbo there for the duration – decided the best way forward was to bring the bass and drums more forward in the mix, pushing the lone guitar back, a technique he’d developed while working with Bowie on The Man Who Sold The World.

A bassist himself, Visconti knew the value of having a strong, textured bass lead the sound. He then embellished that sound with strings, sax, clarinet, keyboards, synthesisers and gongs, adding greater panache to the band’s roughhouse sound.

He also took a firm stance on Lynott’s and Gorham’s spiralling ‘partying’. “It got to the stage where it was affecting work on the album,” he says. “In the end I had to phone management and ask them to get out here and help me sort it out.”

Now recording their third ‘make or break’ album in a year, Gorham says: “What happened to Phil was probably a direct result of that. ‘Jeez, I gotta keep my shit together. I gotta find inspiration. I gotta keep up, man. Hey, chop me out a line of that coke…’ Then next time it would be two lines. We needed that fucking joy juice, man, just to get us up to keep us working. We figured the drugs were the only things that were saving us. Now, that’s a crazy way to think, but that’s the way it was back then.”

Lizzy co-manager Chris O’Donnell duly flew out from London and read them the riot act: you have lost your principal guitarist, your last album was a dud in America, punk is now taking over everything in the UK, if you fuck this album up it’s the end of your career.

“Everything was fine after that,” says Visconti. “The guys knuckled down and we really began making what I still like to think became one of their best albums.”

Most of the songs had been worked out before they arrived in Toronto. Now reaching the peak of his songwriting prowess, Lynott came in with some of his best material, not least album opener Soldier Of Fortune. It boasted a spacy Pink Floyd faded-in intro and a quick lock into deep grooves, Gorham doing a fine job of twinning his own guitars, with Lynott in full-on storytelling mode.

“I started off writing the song to put down mercenaries,” he explained at the time. “Saying how disgusting it was going off and becoming a trained killer. Then as I started to write the lyrics, I began to realise that everybody has a little bit of mercenary blood in them. You know, like sometimes I’m real brutal with chicks – just go after them, get what I want and ‘see you later’. Everything I do and say is to get what I want. So at the end of the song I had to say: ‘I am a soldier of fortune.’ So it wasn’t as heavy as it was initially intended to be cos as I looked more into it, it wasn’t a simple question of black and white.”

This observation lay at the heart of the more mature material Lynott was now writing. Not that Lizzy lost any of their sting, as the title track, which followed, ably demonstrated with its war-drum riff and sneering vocals, though again with a mournful glance sideways: ‘You’re too sly/So cold/That bad reputation/Has made you old…’

A co-write between Lynott, Gorham and Downey, Bad Reputation would replace Sha La La on tour as the showcase for the drummer’s spectacularly percussive solo.

“I remember that riff knocking around for a good while before we recorded it,” Downey recalls. “It was a great number to play. The unusual time signature [6⁄4] was Phil’s idea. Scott and I put the rest of it together, all the little embellishments that really brought the song out. But Phil had the lyrics written before we’d gotten into the studio.”

Side one, as it was in those days, also featured a third utterly climactic Lizzy track in Opium Trail. ‘I took a line that leads you to the opium trial,’ sang Lynott, and you knew he wasn’t making it up.

Again, songwriting credits went to all three band members, but lyrically this was one from the heart from Lynott. In interviews, he would talk convincingly of being influenced by seeing a TV documentary on the Golden States Of Shan – that shit-pool on the borders of North Vietnam, Burma and China where 50 per cent of the world’s heroin trade was then said to come from. “It’s an anti-drugs song,” he would insist, straight-faced.

In truth, Lynott had been dipping in and out of H for heaven for over a year. So had Scott and Robbo. Musically, however, this was Lizzy at another peak, complete with a fiery new Robbo solo. Gorham says: “It was me that talked Phil into bringing Robbo back for some of Bad Reputation. I was trying to get the magic circle back together again and he’s not buying it. But he finally relented. ‘All right, but just fucking keep him away from me…’”

Recalling his brief time in Toronto, Robbo said: “I wouldn’t even fucking speak to Phil the first week I was there, wouldn’t hang out, nothing.”

- Scott Gorham: It would be wrong to kill off Thin Lizzy

- The story behind Thin Lizzy's Dancing In The Moonlight

- The 10 Best Thin Lizzy tracks, by Brian Downey

Visconti later recalled how after Robbo had completed his solo on Opium Trail, “I invited him back to the control room to hear the playback. He just said no, he’d rather not, and left. It was a pity because it was a great piece of work.”

Eventually, a rapprochement was tentatively entered into. But the bond was fragile. “Me and Scott always got on great with Robbo,” says Downey. “But it had got to the point where Phil and Robbo weren’t even talking. Then in the studio with Visconti, they gradually got it together again. They were talking, at least.”

The rest of the album’s six tracks were split evenly between the good and the great. The good: the poignant Southbound, the phoned-in Killer Without A Cause (The Boy Are Back… but only some of them), and the gently contrived Downtown Sundown. Lynott said of the latter song: “Because I wrote Don’t Believe A Word, every chick I went out with after that used to throw it back in my face – ‘I don’t believe a word you’re saying.’ So I figured I’d write a song that was actually a statement of love, so this would be an answer to it, and there’s a line in it that goes, ‘Please believe in love, I believe there is a God above for love,’ you know?”

The great: the lilting, loitering chocolatey pop of Dancing In The Moonlight, destined to become the album’s signature single and Lizzy’s biggest and best hit song after Boys; and That Woman’s Gonna Break Your Heart, a wonderful big-sky production, with Robbo allowed back in to add his distinctive lead flourishes over Gorham’s taut acoustic strum-a-thon. It could have signalled a whole new direction for Lizzy, beyond the jailhouse rock and into the wide blue open of orchestral pop.

And then there was the album’s most impressive moment, Dear Lord. Co-written by Lynott and Gorham, Dear Lord was the closest Thin Lizzy ever got to pure artistic transcendence. The music is sweeping, epic, again closer to Pink Floyd than the quasi-metal outfit the band would shrink to in the 80s. Lynott delivers one of his deepest, most honest, no-jive lyrics, with its exquisite pay-off: ‘Dear Lord… I believe your story now you believe mine.’ Lynott on the phone to God: not praying, just saying, with angelic backing vocals by Visconti’s wife, Mary Hopkin.

According to Gary Moore, speaking years later, Lynott – who would publish his second volume of poetry, simply titled Philip, around the same time Bad Reputation was made – was a wordsmith first, singer second, bassist third.

“He’d spend more time on the words than the music because he found the music not that difficult. They were very simple songs, you know? He’d play you Dancing In The Moonlight on the acoustic guitar and you’d go, ‘Is that it?’ Then you’d hear the finished thing and understand what he’d been so enthusiastic about because he was hearing it as the finished thing in his head.”

With Dancing In The Moonlight and Bad Reputation released as a double A-sided hit single in the summer of 1977, and pre-release reviews for the album glowing, the band, with Robbo back in tow, headlined that year’s Reading Festival.

They were back where they belonged – on top, mama, better get your fuck-on below. The album reached No.4 in the UK, making it their biggest-charting hit. Yet when it came out in America, it barely touched the sides, dragging its heels as far as No.39, then falling off its horse again.

“Bad Reputation was definitely an improvement on Johnny The Fox,” says Brian Downey. “But it didn’t do very much for us in the end, even though it was a great album. The problem was that by then the band did have a bad reputation, certainly when it came to America.”

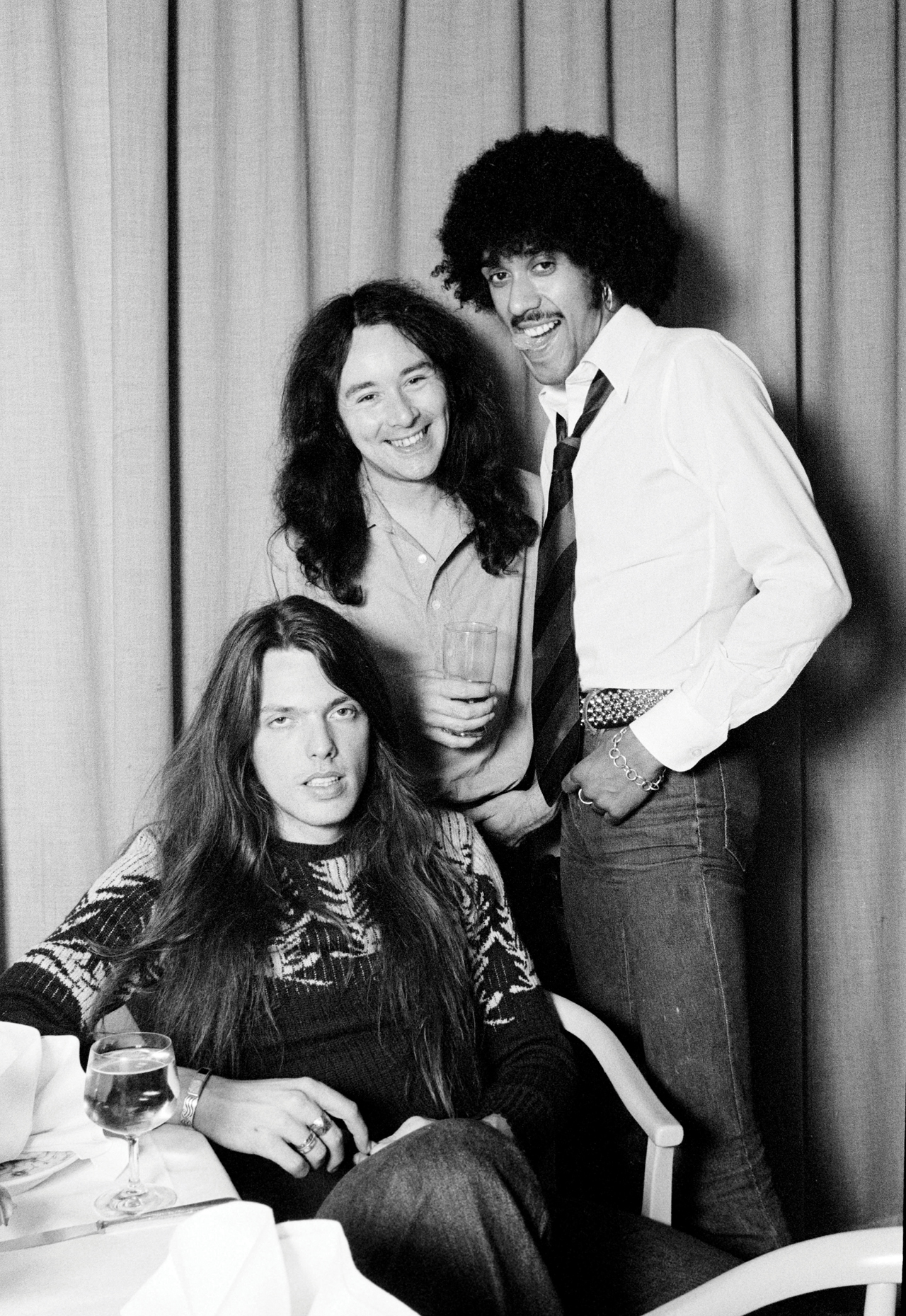

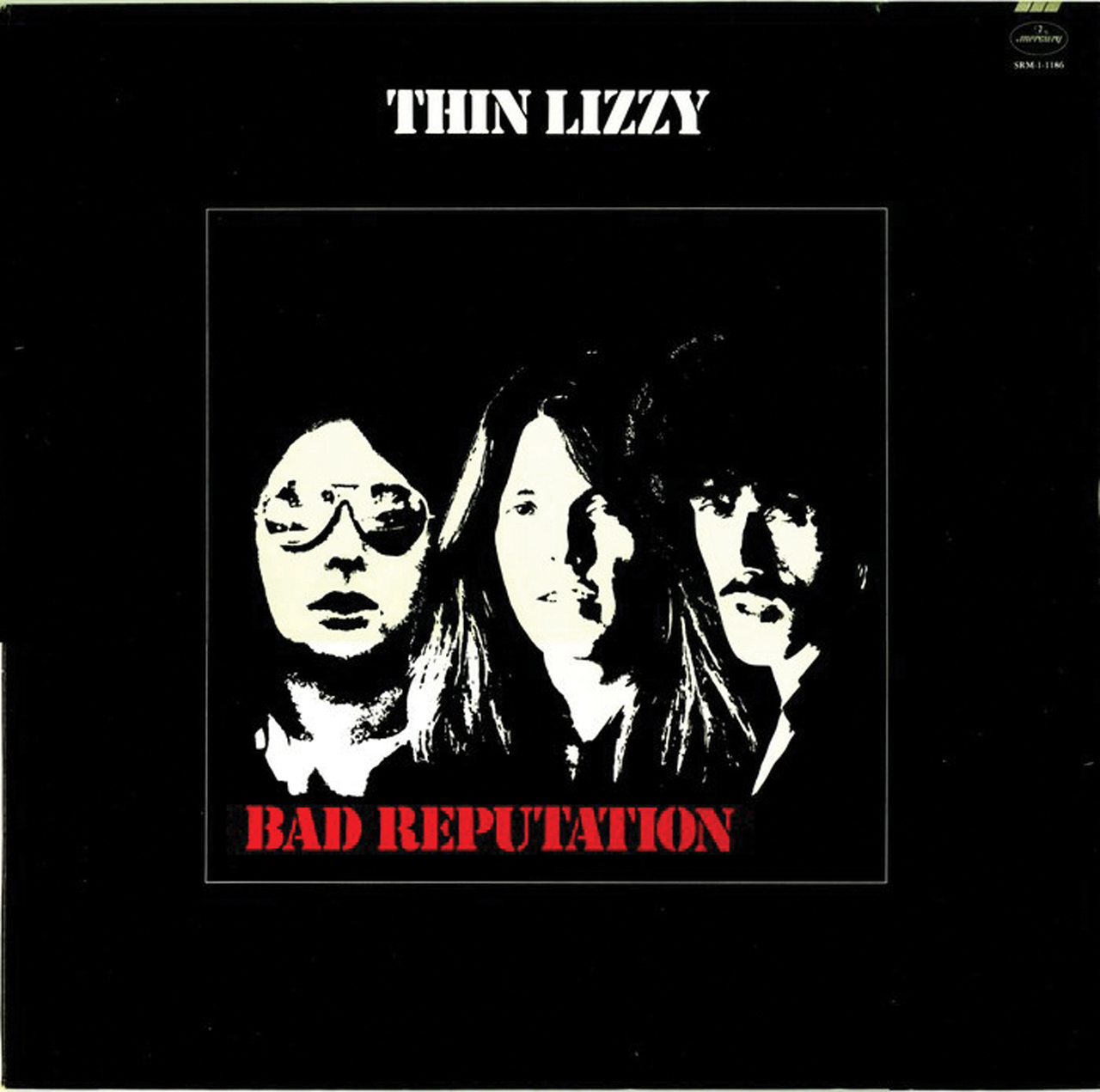

When the front cover of Bad Reputation carried a simple black-and-white picture of just Downey, Gorham and Lynott – no Robbo – it only served to underline how much the band’s mystique had mushed into misunderstanding.

Downey says: “I didn’t agree with that but I was outvoted. Everyone just wanted the three of us because everybody knew that after this album, Robbo would be gone.”

In fact, Robbo continued ‘guesting’ with the band for another 12 months. But it was getting hard to keep up with what was really going on. Getting harder to care.

The aftermath of Bad Reputation found Thin Lizzy living in a world where on one side of the planet – Britain, Europe, Australia – they had never been bigger, while on the other – Am-er-ee-ca – they had effectively blown it.

“Every now and again something would come along that seemed to stop the band in its tracks. And that seemed to happen a lot,” says Downey. “Especially over those years when the band was on a crest of a wave. We had so much bad luck.” He pauses, then chuckles. “We could have avoided it by living a bit more cleanly but it’s easy to say that now. That’s the way the band was back then. There’s no getting away from that.”

Drugs were normal; to be encouraged, in fact. “Yeah,” Downey says. “It makes my eyes water now just thinking about it.”

Instead of following Queen and Led Zeppelin into the frontline of American rock mythology, Thin Lizzy now found themselves being lauded by the new wave of punk stars who saw them as the rule-breakers of rock royalty – one of us, guv.

“We thought of ourselves as the street punks of that era,” says Gorham. “All the other rock bands of the era were slick, vocal harmonies. We weren’t like that. So when the punk thing came around, Phil just embraced it. ‘Thank fuck, man! There’s other people out there like us!’”

Lynott also saw the credibility by association factor of being photographed with Sid and Nancy, Bob Geldof and Midge Ure, and playing gigs around London – half-Lizzy, half-Pistols – as the Greedy Bastards.

“Phil was always very media-savvy,” says Gorham. “Phil loved doing Top Of The Pops. He just loved being on TV. We would go out and do a video and nobody would play it because there was no MTV in those days, so it would become this whole financial waste of time. But by God we had a video!”

It was around this time that the music press began spritzing rumours of Lynott starring in a movie about Jimi Hendrix. It wasn’t true, but as Gorham says, “Phil never denied it because it was a great story and got a lot of press.

“Phil knew the value of print, he knew the value of a picture in a magazine. He had it down, he had a map, he just knew this shit. We would do millions of fucking photo sessions, getting dressed up in different outfits. Then right at the end of every shoot he would say: ‘All right, now let’s have a nice little smiley one for the teeny mags’ – which I fucking hated. But he was right, of course, because those mags did use those shots. You never had to beg Phil for a picture. Even the drug busts he loved. ‘Hey man, you see my drug bust in the paper?’”

It would be another two years before Lizzy recorded another original album, the void filled with Live & Dangerous, officially Robbo’s last release with the band, and still their best-selling collection. It was only kept from No.1 in the UK by the Bee Gees’ Saturday Night Fever soundtrack.

Convinced Lizzy had gone as far as they could go, Lynott also looked seriously into the possibility of making a solo album. He’d been talking about it since Rod Stewart abandoned his band, the Faces, for a successful solo career in 1975. “Phil thought he could be the new Rod Stewart,” says Downey. “He had the looks and the gravelly voice. He even talked to Rod’s management about it.”

In the event, Lynott would have to wait until 1980 before seeing that dream come true. Meanwhile, Robbo was ousted for the last time.

“We were all hoping Robbo would stay on the straight and narrow but he’d fallen off the wagon again,” says Downey. “Robbo and Phil weren’t getting on too well again. I personally didn’t want to see the most successful version of Thin Lizzy falling apart before we’d even got started. I thought this should be sorted out. Hopefully it’s just a passing phase. But it just kept going on. Every time we went on tour, some sort of argument cropped up and the animosity started all over again.”

It came down to it being either Phil or Robbo who would have to leave. No contest. “I think Phil would have walked if Robbo didn’t.”

Gary Moore now came back in. Lynott agreed to appear on three tracks on Moore’s 1978 solo album, Back On The Streets – including the original, slowed-down, soulful version of Don’t Believe A Word and a new co-write between the two, with Lynott on lead vocals, entitled Parisienne Walkways. But again, the clouds came back when the latter track became a hit single, and both men verbally scuffled over who deserved the most credit.

Looking back now, 40 years on from its release, it’s impossible not to see Bad Reputation as both the peak of Thin Lizzy and the beginning of a long, drawn-out end. Brian Downey walked out not long after Gary Moore rejoined. “I was burnt out,” he says. “My health was really suffering. I needed to get away.”

Enticed back for the Black Rose album in 1979, only to see Moore walk out for the third and final time halfway through the subsequent American tour, Downey looks back now on what he calls “the Thin Lizzy curse” with the admirably balanced perspective that only time and space can bring.

“I try to forgive the bad and focus on the good times. In the studio, we never did 25 fucking takes of anything. On albums like Bad Reputation, if things weren’t happening, Phil would always come up with a master plan to save the song. ‘Okay, this is the new arrangement I have an idea for.’ And the new arrangement would normally work. That just shows you how talented Phil was.”

And how brilliant and unique Thin Lizzy really were. And why their real reputation will outlive them forever.