John Baizley rolls his sleeve all the way up and stretches his left arm out in front of him. There, running like a miniature pink river from his lower forearm to just below his shoulder, is a vivid, half-inch-wide scar. It’s a permanent reminder of where the doctors at the Royal United Hospital in Bath opened up the Baroness singer/guitarist’s arm to save it from amputation.

“My arm was reconstructed,” he says in a voice that sounds more matter-of-fact than you’d expect given the potential outcome. “The humerus bone was broken into 12 pieces immediately after the accident. My arm was bent 180° backwards. I had to break it twice to get it in front of me. That pain you feel once or twice a year that’s incredibly sharp and nauseating is basically what I feel all the time. I’m talking about something I wouldn’t wish on anyone.”

It’s just over three years since his life was turned upside down and inside out following a horrific bus crash on the outskirts of Bath that left all four members of Baroness and five others hospitalised with injuries of varying severity. Such was the trauma of the accident that only John and guitarist Pete Adams remain from the lineup involved in the crash (drummer Allen Blickle and bassist Matt Maggioni left soon after, replaced by Sebastian Thomson and Nick Jost respectively).

For John Baizley, at least, that trauma is ongoing and will be for as long as he lives. And just as it impacts on every aspect of his life, so it has become fused to his band’s entire existence. Baroness’s fourth album, Purple, finds the frontman channelling pain into art. ‘When I called on my nursemaid, come sit by my side,’ he sings on the album’s near-seven-minute centrepiece, Chlorine & Wine, ‘but she cuts through my ribcage and pushes the pills deep in my eyes.’

“I can’t help it,” says John, perched on a sofa at Hammer’s HQ. “Every moment of my life is dictated by what happened on August 15, 2012. I have 24-hour-a-day, 365-days-a-year pain. It nauseates me persistently. Along with that comes a whole host of auxiliary issues. And those are basically the themes of the album.”

The shadow of what happened three years ago looms large over Baroness, to the point where it’s easy to forget what a unique and compelling band they are. Their third full-length album, 2012’s experimental double-disc Yellow & Green, transcended the riff-heavy approach of its predecessors. It was the sound of a band busting through the restrictive walls of the underground metal scene they rose up through. Yellow & Green had been on the shelves for less than a month when their tourbus crashed. Purple sounds like the work of a band picking up where they left off before they were almost terminally interrupted.

John is incredibly candid when it comes to details of the accident, and the specifics of what it did to his body and mind. When the crash itself comes up, as it inevitably does, he doesn’t hold back.

“I never blacked out during the accident,” he says. “But there was a moment where things went dark for me. The best description I’ve come up with is that it felt like my nose was against a matt black mirror. It was like I was staring into this mirror that was cold and devoid of light, devoid of anything. I realised then that death is a lightswitch – you’re off, and beyond that is nothing. Maybe it’s true, maybe it’s not, but that’s how I feel. That’s what was shown to me.”

That nobody died in the crash was a miracle. Emergency services arrived on the scene and cut people free. John was taken to hospital in nearby Bath, where surgeons debated whether his arm needed amputating. He remained in the UK for three months, unable to fly home. When he did finally return, he was confined to a wheelchair. And that’s when his physical and mental recovery truly began.

“I’m sittingin my studio, in a wheelchair, staring at my guitar, going, ‘Alright, me and you got some work to do…’”

It’s hard to suppress a laugh at the thought of a man in a wheelchair having a conversation with an inanimate musical instrument. He notices and waves it off.

“No, no need to apologise. I have to laugh at it myself. If I’m not laughing, then I’m really not in a good place.”

It took him a week and a half to pick up the guitar, and when he did he could barely feel the strings. But he strummed three chords: a G, a C and then an E. For the next two weeks, he played every day. He got a little better every time. In those early days of recovery,did he ever think Baroness might be over?

“No,” he says. “Well, maybe the first two days [after the accident]. Because they were going to amputate, definitely. When that was the discussion, I thought, ‘Well, that’s that.’ But as soon as the surgery was over and I could move my fingers, it was, like, ‘Nah, we got it.’ I was being cavalier, but it was then that I hung my definition of recovery on the ability to perform.”

Pete Adams is the man who keeps Baroness grounded. A plain-speaking, straight-backed Southerner, he remains their strongest link with the metal scene.

“I’m the one in the band who pushes for heavy at all times,” he says. “I like classic, heavy rock’n’roll. The heavier bits of Yellow & Green were me.”

The guitarist was also the only member of Baroness to emerge from the bus crash largely unscathed, and there’s a good reason for his attitude. In the early noughties, Pete served in the US military in Iraq. He was part of the first wave of troops to enter Baghdad and, later, Fallujah. He was severely wounded when a grenade exploded near his face; he lost the sight in one eye after an optic nerve was severed (he was subsequently awarded a Purple Heart medal).

“I’ve seen so much death and so much destruction on such a large scale, the kind of stuff you only see when you’re in full-scale war. This bus crash, it was a bad day, yes, but we all survived. We didn’t lose any life or limbs. Not a soul, man. We beat that. We’re winners.”

He watched his bandmate’s gradual rehabilitation with a mixture of concern and unspoken pride. “John and I have been friends for over 20 years, and I’m very close to his wife and his daughter,” says Pete. “It’s always tough to see someone you’re close to going through their thing, but you have to have to let it play out. Everybody’s going to handle things differently. John definitely handles things his way.”

Looking back, John says the trauma of the crash left him: “emotionally flatlined – there wasn’t really sadness, there wasn’t really joy, there was just ‘Get through the day’, or ‘Ouch, that hurts’.” It was, says Pete, PTSD – or Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder.

“I was very candid about how I was feeling,” says John. “I could explain things like this: ‘[Dead-eyed, emotionless voice] Yesterday I had a horrible day, and I’m not sure I’m comfortable living like this for the rest of my life.’ There was literally no emotion of any sort to put into it.”

Hearing somebody say they’re not comfortable living like they’re living for the rest of their life is worrying. You’re not talking about suicide, are you?

“It’s not like I’d rather not be alive. But it’s a great source of discomfort and frustration and anxiety for me to realise that, very literally, it’s not going to ever feel better than it does right now, and it doesn’t feel good right now. If I contemplate 10 years, I can get incredibly depressive. Thirty years, it’s like calculating infinity. My brain will shut off at some point, because I can’t imagine that many groans, bangs, dents, bruises and pain.”

Baroness began writing what would become Purple in January 2014, though it would be several months before they entered a studio to record it. The focused approach of the new album – especially compared to its predecessor – was a conscious choice by the band. “I like bleak, dark music,” says John. “I was bleak and dark myself. But the best idea was when we decided to play towards the strengths of writing something focused and energetic.”

For the frontman, making Purple was a form of catharsis. “I won’t write a song about something I can discuss and contend with outside of music,” he says. “That’s what music and art is for me. It’s a way that I avoid the fact that I’m actually conscious that I’m losing my sanity, bit by bit, with each day.”

Do the bad days outweigh the good?

“The pain outweighs the pleasure, for sure. But I’m not going to let something like that deter me from chasing something.”

This will sound ridiculous, but did anything good come out of the whole thing?

“Yeah, a lot of good came out of it. It’s simple just to focus on the bad stuff. The good thing is that every thought I had about the value of life was strengthened. In feeling that pain that I felt when it happened, I was filled with a profound joy, an overwhelming amount of love for the pure existence of my life. In order to learn that lesson, I have to now pay for it. There was a price for that lesson.”

What have you learned about yourself over the last three years?

“I’ve learned that the physical part of us is very fragile,” he says. “That seems very obvious, but I mean it in a way that I have to respect it. And I’ve learned that the art I make and the music I’m part of is truly exhilarating. It can relieve those things that are major league bad things for me. It sounds like a platitude when most people say it – maybe it does when I say it. But I do need it. My sanity is at risk if I don’t have it.”

Purple is out on December 18 via Abraxan Hymns

Hue Romance

Baroness leader and artist John Baizley talks us through his most iconic sleeves.

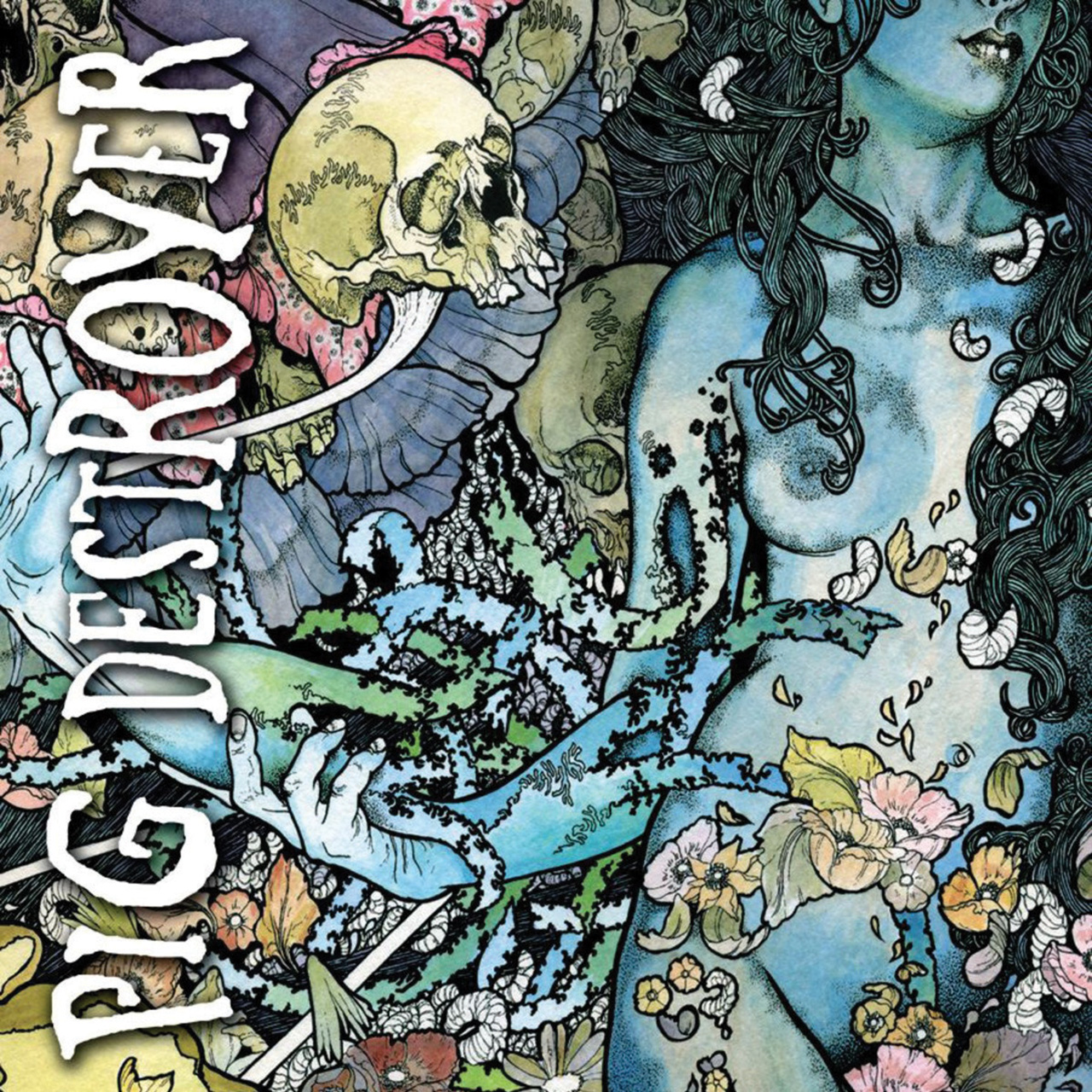

Pig Destroyer, Phantom Limb (2007)

“The first piece of art for a sleeve I did was for Baroness’s First EP [in 2004]. It was fairly crude – I hadn’t locked in a style yet. But the first album that helped define the direction I continued in was Phantom Limb. I saw it as an opportunity to decontextualise grindcore, which can be really macho and aggressive. Here was this band writing music and lyrics with this artistic flair, and I thought, ‘Wouldn’t it be awesome to present a cover that subverted many of the paradigms of that scene.’ It was a great turd in the punchbowl.”

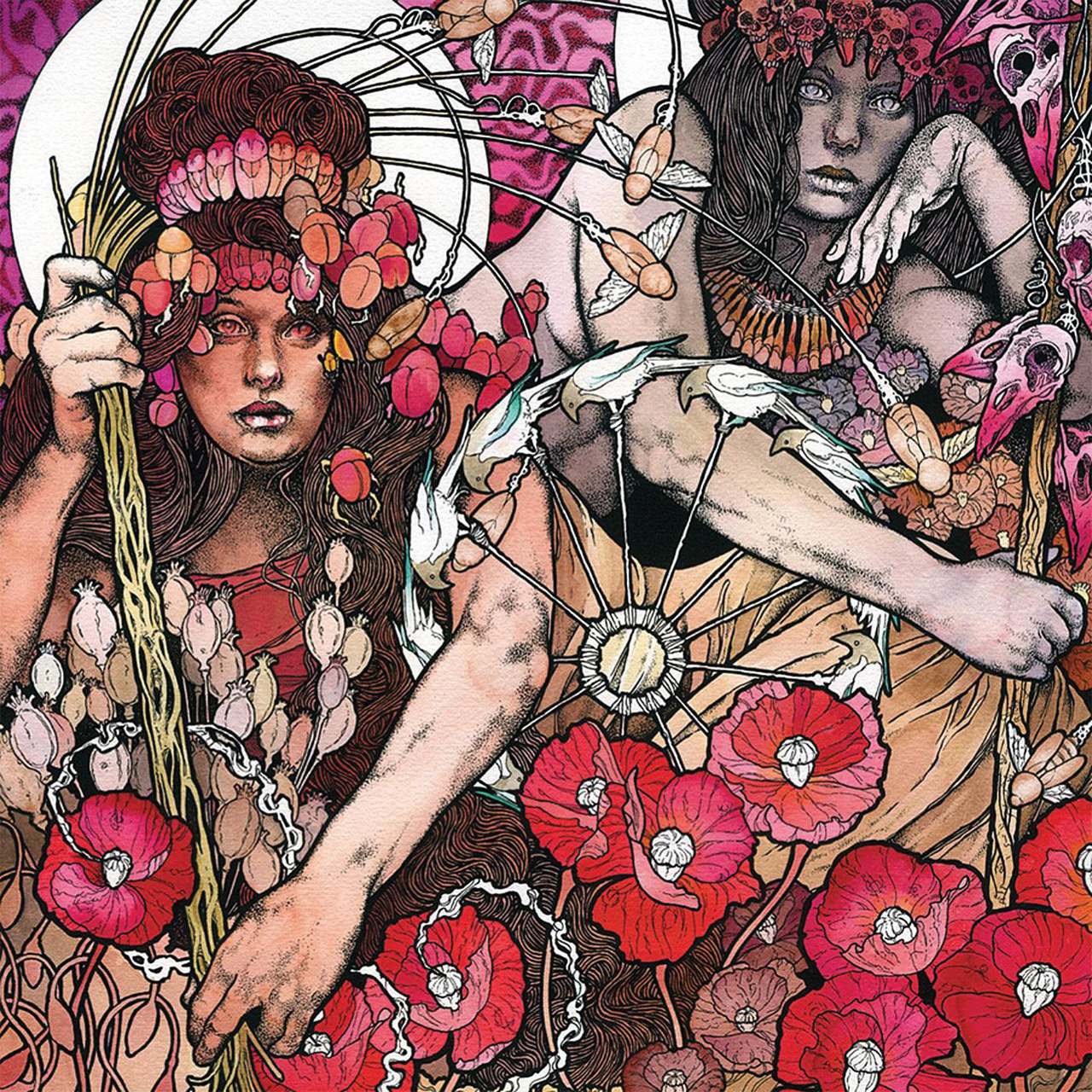

Baroness, Red (2007)

“That was the album that helped give the band a visual identity. We didn’t want it to be about the names and faces of the four people. Neurosis or Pink Floyd or Black Flag – they were bands who had an aesthetic that was consistent and pure. There was no leeway in terms of making concessions. That’s what we trying to do at the time.”

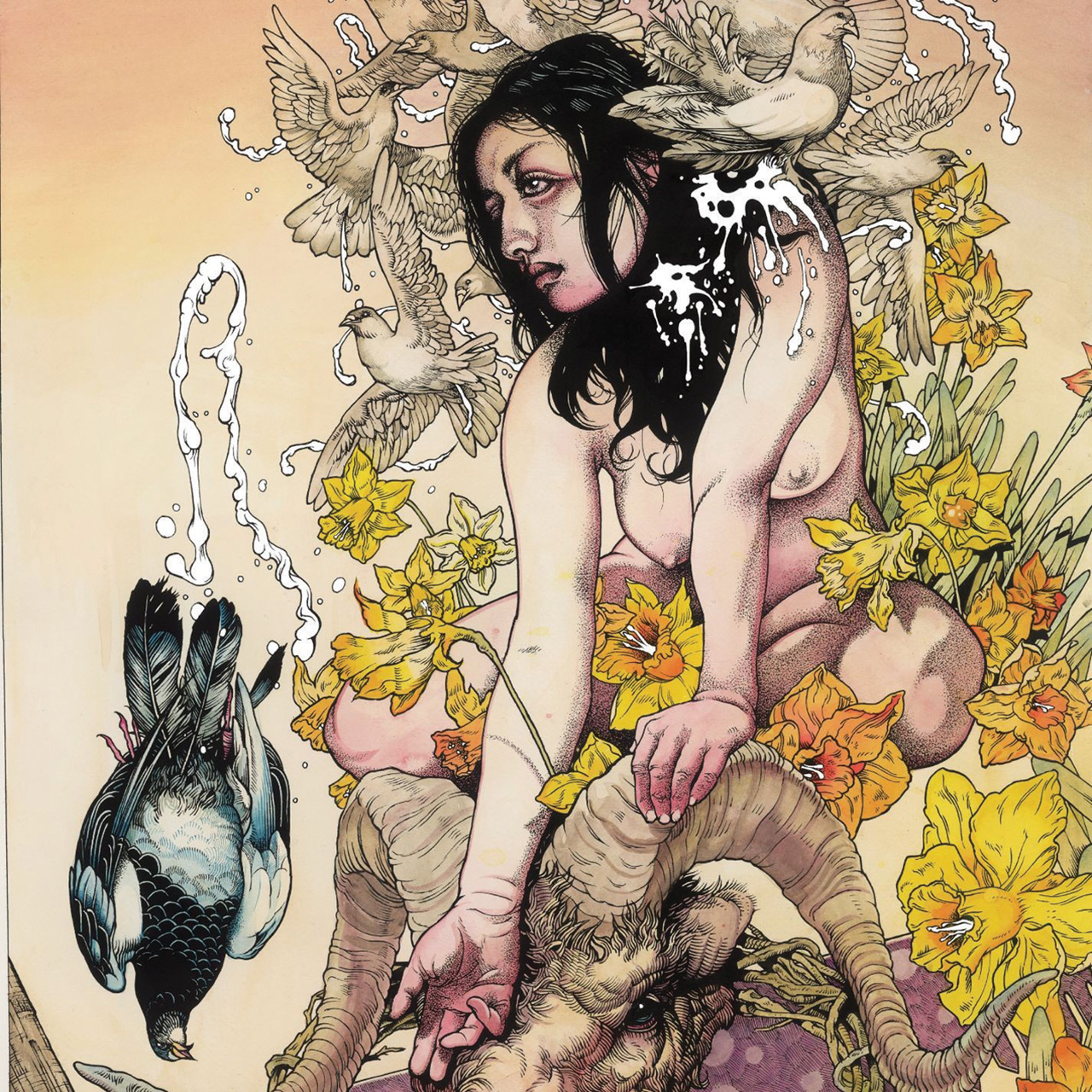

Gillian Welch, The Harrow & The Harvest (2011)

“She’s the very top of the shelf with the music she plays – it’s a real stark, Americana sound. I have some mutual friends with Gillian and [husband/producer] Dave Rawlings, and they showed her my artwork. She responded really well to it. She thought the same thing that I think: ‘Let’s forget what ‘needs’ to happen, let’s change things a little bit.’”

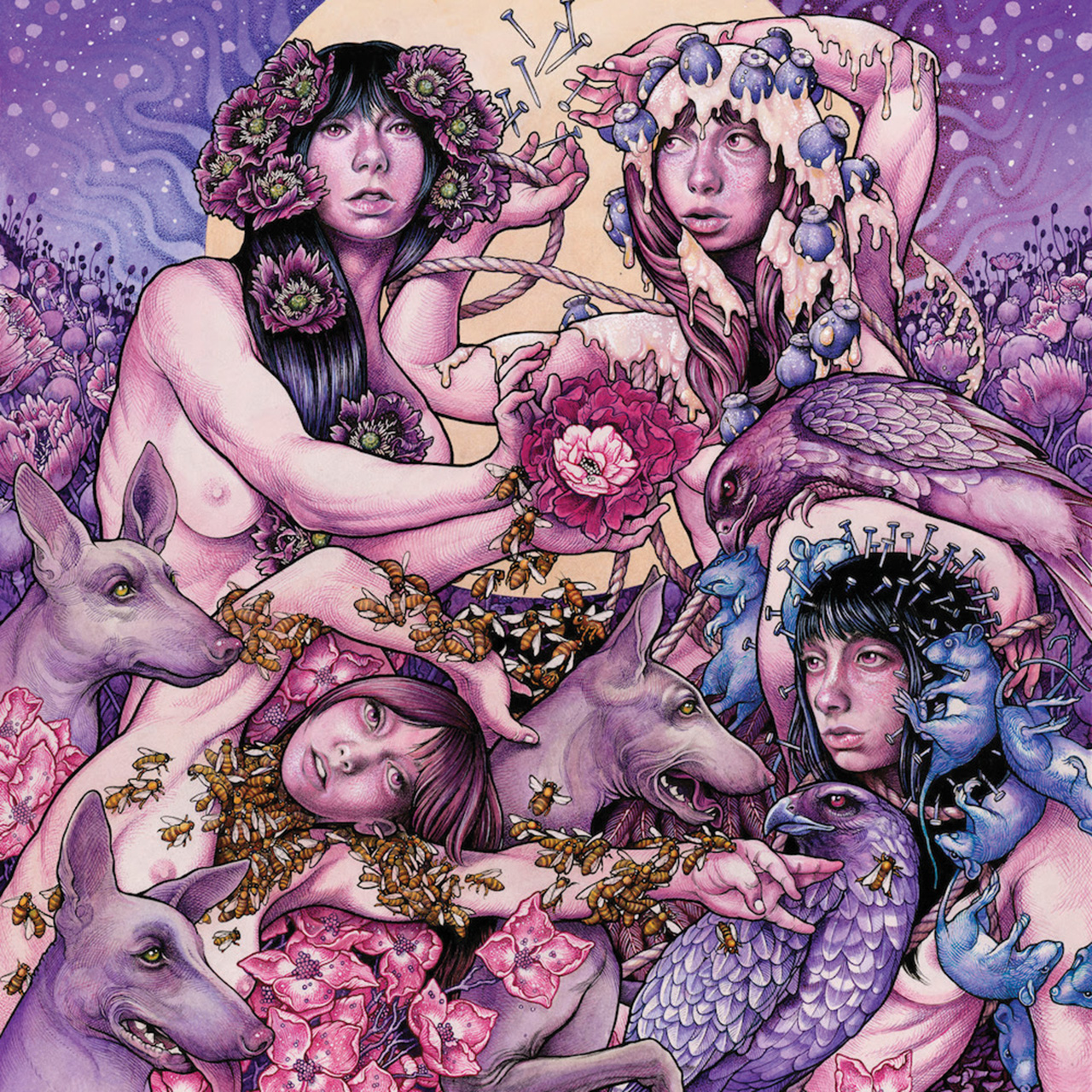

Kvelertak, Meir (2013)

“I consider these pieces art, not commercial illustrations. And I like to think of the images in Jungian terms – everything is an archetype. The women, like the one on Meir, aren’t specific characters – they’re sort of vehicles for the message. And I take great pains to make sure there’s not an overt sexual element to what’s happening. But an image should elicit a reaction. Extreme music is extreme, and the visual part should push against the audience as much as the music does.”

Baroness, Purple (2015)

“Each colour I use has different meanings to different people – cultural, social, visual. But there’s also an arbitrary nature to it. What’s the significance of the colour purple? I could probably bullshit my way through a two-hour discussion about why it’s purple. I might be dead on, personally, but it might contradict what everybody else thinks. So make what you will of it. It’s open to interpretation, as it should be.”