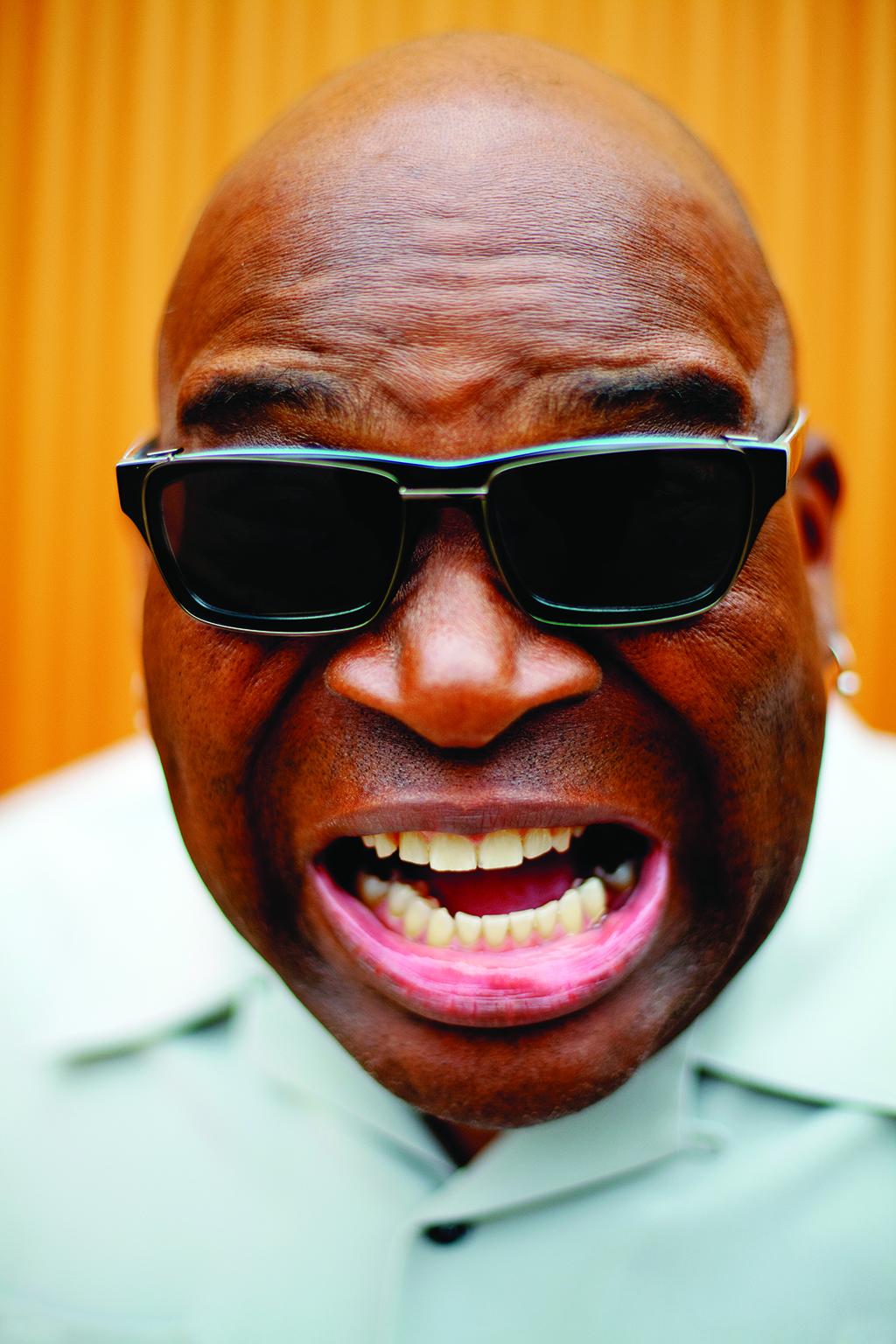

It’s 1983, almost midnight in a tiny bar in downtown Baltimore. Barrence Whitfield, the charismatic lead singer of The Savages, stands centre stage, hands gripping the mic tightly, rivulets of sweat running down his face.

His shirt is ripped, his trousers in tatters. As he takes a breath, The Savages, led by former DMZ and Lyres guitarist Peter Greenberg, launch into a frenzied cover of the obscure R&B song Mama Get Your Hammer by the Bobby Peterson Quintet. As Whitfield screams, his shot-to-bits testifying tears up the joint. He starts running up and down the stage, rolling around on the floor, crawling through Greenberg’s legs, jumping off the drum riser. “And then I try to run up the walls,” says Whitfield down the phone today. “I guess I was thinking I’d do some kind of James Brown-styled backflip. Instead I end up putting a hole in the wall. When the show is over, the manager comes up to me, I thought that’s it, we’ve had it, he’s going to tell me we can’t play here any more. But he gives me a pen and asks me to sign the wall by the hole.”

Born Barry White on June 13, 1955 in Jacksonville, Florida to a father who was “a jazz nut” and a mother who loved Jackie Wilson and Aretha Franklin, Barrence Whitfield had little choice but to get involved. “We moved to East Orange, New Jersey when I was three,” says Whitfield, who to avoid confusion with Barry White, the 70s soul singer, adopted his Whitfield moniker in tribute to Motown producer Norman Whitfield. “It was the 60s, long sweaty summers, poor air conditioning, I was drinking a lot of pop, eating a lot of ice cream, listening to the radio blaring out of opened windows. Everyone listened to local station WNJR – it was a wholly black station, it played a lot of Motown. I also got to hear OV Wright and Clarence Carter and James Brown on it.”

Every Friday he visited the local record shop. “I’d go buy 45s then race home to play them on the old record player we had. My first 45 was The Temptations’ I’m Losing You, my first album was by Paul Revere And The Raiders, and I always got the latest James Brown release. James Brown seemed to have a record out every week back then.”

James Brown was pivotal in Whitfield’s musical education. “James Brown blew my mind, “ he says. “I mimicked his scream and shout, how he commanded the stage, dropping to his knees, spinning round. I wanted to be just like him.”

The Bethel Missionary Baptist Church situated across the street from where he lived was also important. “They’d shout and scream and whoop and clap while praising the lord. I learned a lot of skills singing in the gospel choir there and seeing gospel groups like The Dixie Hummingbirds and The Swan Silvertones, although every time Jackie Wilson came to town my mom got dressed up in her Sunday best and said, ‘We’re not going to church, we’re going to see Jackie Wilson.’ I learned from him too.”

Once at West Side High School he grabbed every opportunity to perform, “from taking part in productions of Broadway shows and musicals to playing in soul and funk bands.” One named The Funkasonics, in which he played drums, paid tribute to George Clinton and P-Funk (“we worshipped Funkadelic”). Another outfit pledged allegiance to the Black Panthers, while another saw him teamed with three white boys singing Led Zeppelin’s Immigrant Song. “Seeing a black guy screaming Led Zeppelin songs shocked a lot of people,” he says.

In 1977, after graduating high school, Whitfield relocated to Boston to study journalism at Boston University.

In 1979 he made his recording debut as a member of Sharp. Combat Zone, penned by Steven Sharp and Frank Murray and produced by Sharp, was recorded at Intermedia Studios in Boston and issued on the Random label. It featured Whitfield as lead singer. “It was masterminded by these two guys I knew from New Jersey who were studying at the Berklee College Of Music in Boston,” he says. “They wanted to do a 45 for their class project, they knew I had sung in bands and called me up. The studio was owned by members of The Cars, and The Combat Zone was an area off downtown Boston long since gone that was all X-rated movies and strip joints. The 45 got played on local radio. That was my introduction to the Boston music scene.”

It took another four years, though, for The Savages to form. By 1983, Whitfield was working in Nuggets, a cool record shop in Boston where local musicians hung out. “It was through working there I met Peter. A friend of mine who also worked there had heard me singing, harmonising with the records we played in the store. He said: ‘My friend is looking for a singer, you should meet him.’ Peter came by the store and we talked. I didn’t know he was a legend already, that he’d done DMZ and The Lyres.”

Greenberg invited Whitfield back to his house and over a steaming pot of chilli the pair bonded. “We were eating and he started playing me records, really great stuff like Mama Get Your Hammer and Wild Hog Hop by Bennie Hess and Miss Shake It by Ba Ba Thomas and Georgia Slop by Jimmy McCracklin. We stayed up all night listening to records. I didn’t sing a note but he said to me: ‘I’ve got my guy.’ It was great because when we talked about the band, he wanted me to scream so I went back to those old James Brown and Wilson Pickett records of mine and I started to develop that scream. I wanted to be Esquerita and James Brown and Archie Brownlee from the Five Blind Boys Of Mississippi. I wanted to let it go like Little Richard.”

For the next six months they sat in a rehearsal space, “getting everything to do with our sound just right and then after just one show it snowballed, there was no stopping it. No one was doing what we were doing in 1983, playing fierce with energy. It wasn’t just me who was throwing my all into it, Peter would come off stage with his wrists all bloody. It was chaos every night.”

Their storming rock’n’soul revue quickly secured them a following through word of mouth.

Their self-titled debut issued on US label Mamou in 1984 expanded it. Recorded live to tape at Perfect Crime Studios in Watertown, Massachusetts, it captured their onstage excitement perfectly. Originals such as Walk Out and Ship Sailed At Six pinned Whitfield’s howling to wailing sax and rockabilly guitar while covers of live favourite Mama Get Your Hammer and Don Covay’s wild rockin’ Bip Bop Bip were dynamite. In 1989 in New York, Whitfield leading a reconfigured line-up of The Savages was joined by Covay for a version of the song. “I was in total shock,” he recalls. “My guitarist was working with [Funk Brothers drummer] Benny Benjamin and next thing I know this guy wearing real dark shades jumps up on the stage and launches into Bip Bop Bip. I’m like, oh my God, it’s Don Covay!” Whitfield also contributed to Back To The Street: Music Of Don Covay, a tribute album of covers of Covay songs.

After the band’s second album, 1985’s Dig Yourself for Rounder, which saw The Savages traversing similar territory, Greenberg left the group. “It wasn’t a case of anything going wrong or us falling out, Peter wanted to go back to college [to study environmental engineering], get married, have kids.”

The band dissolved, but within six weeks Whitfield had put together a new Savages. “I felt we’d come too far to let it dissipate,” he says.

Radio 1 DJ and Savages fan Andy Kershaw brought the band over to the UK to play London’s Dingwalls, for a show that ended up with them receiving the thumbs-up from a rock’n’roll legend. “That’s how we found out that Robert Plant is a fan,” says Whitfield. “He calls up Andy, his sister Liz Kershaw answers the phone, when he says he’s Robert Plant, she’s like, yeah right, then sing me Stairway To Heaven, which he does! When he gets to talk to Andy, he says, ‘I hear you’re bringing Barrence Whitfield & The Savages to London, can I get on the guest list?’ Andy’s like, ‘Bloody hell, just come’, and he does. That night he tells me how he loves our first record, how it’s real rock’n’roll.”

Bo Diddley and George Thorogood were impressed by Whitfield’s hard rockin’ style of R&B too. After 1987’s third album Ow! Ow! Ow!, Whitfield secured support slots with the pair. Whitfield remembers their first meeting: “One night we’re playing the Lone Star Café in New York. We set up and look out and Bo Diddley’s sat there. Of course I have to go over there and tell him what a huge fan I am. Then I look up and at the next table was Doc Pomus, so I went over and talked to him for a bit, then we get towards the end of our first set and who walks in? George Thorogood. He’s smoking this cigar and as I let out this scream, it just falls from his mouth. He comes backstage in the interval then just as we take the stage for the second set he grabs the mic. ‘I just want to say a few words,’ he says, ‘Wow! Barrence Whitfield & The Savages. Wow!’”

In 1990 Whitfield worked with Jim Dickinson on Let’s Lose It, before recording two country albums with Tom Russell, 1993’s Cowboy Mambo and Hillbilly Voodoo. Whitfield continued to perform into the 2000s, then in 2010 Ace Records reissued Barrence Whitfield & The Savages’ first album. “It was that that got Peter and I back together,” he says. “I went to see Peter in New Mexico as it was being put together, he had a band going out there and I said if you ever need me to do some vocals… and two weeks later, he calls: ‘I’ve booked five gigs, I’ll fly you out.’ And suddenly we’re sitting in his home and talking about getting back together.”

2013’s Dig Thy Savage Soul, recorded for Bloodshot Records, caught the reunited group on top form. The brief for the record was simple: “We just wanted to get dirty and nasty so we recorded the band around one mic on an 8-track as if we were playing a live show.” The album opener The Corner Man is a no-holds-barred rewrite of garage icons The Sonics’ Boss Hoss with a Chuck Berry duck walk. Covers of Jerry McCain’s Turn Your Damper Down and Lee Moses’ I’m Sad About It are ace too. In their hands, the former is a hard-edge-voiced raging rocker with a furious rockabilly beat, the second burns with gospel fire.

A support slot with The Sonics followed. “It was a genius pairing,” says Whitfield. “It was the old one-two punch. We’d get the crowd revved up and they’d come out and finish them off. We became bosom buddies while we were on the road together. It was one of the best tours we’ve ever done. And it got us ready for recording Dig Thy Savage Soul’s follow-up.”

That follow-up, Under The Savage Sky, was recorded over two weeks at Ultrasound Studio in Cincinnati, Ohio. “The first week we were learning the songs, the second week we were hammering them down live. It’s all pretty intense stuff.”

It certainly is; from the crazed original of Incarceration Casserole to covers of Timmy Willis’ I’m A Full Grown Man and Kid Thomas’ The Wolf Pack, this is trademark Savages’ wham-bam-thank-you-mam red hot R&B, and it takes no prisoners. “With every record you want to go in and do something better than the last, to get on your groove and ride it.”

Barrence Whitfield & The Savages’ new album Under The Savage Sky is out now via Bloodshot Records.

Savage World

The five 45s that made the man.

James Brown

Papa’s Got A Brand New Bag

King, 1965

Every black family in America owned his Live At The Apollo record – you’d go to someone’s house and there it was – but the one that really got me was this 45. In 1965, I was 10 and hearing that coming out of the radio, wow! It sounded like nothing on earth. It was so funky. I needed to own a piece of that.

Howlin’ Wolf

Spoonful

Chess, 1960

I saw a photo of him first and I just knew he was going to sound bad, and then I heard his voice and again, it sounded like nothing you’d heard before. He just growled at you and the backing, the energy, the rawness, it can’t be beat, still today.

Little Richard

Lucille

Specialty, 1957

They played this on the radio and I immediately needed to know more, he sounded wild and untamed. I got to meet him in 1987. We were playing a festival in Belgium, the promoter took me to his hotel room. I was shellshocked, in complete awe. I have a photo of us cheek-to-cheek.

Otis Redding

I’ve Been Loving You Too Long (To Stop Now)

Volt, 1965

My mom listened to this all the time and I kept taking her record and playing it. It got to the point where she said: “Go buy your own copy.” It was a staple of my adolescent listening. His vocal is amazing.

The Rolling Stones

(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction

Decca, 1965

The Beatles came to the US and changed everything, but it was the Stones records I bought back then. The Stones really caught my ear, they were a force to be reckoned with.