On June 3, 2004, the body of Thomas Forsberg was found in his apartment in a suburb of Stockholm. The 38-year-old had died of an undiagnosed heart defect, but beyond that, little was known about the circumstances of his last few days, or his death.

It was a tragedy that someone so young had passed away so unexpectedly, but the lack of detailed information about his death was strangely appropriate. Thomas Forsberg was better known as Quorthon, founder and sole member of Bathory, the cult ‘band’ who helped spark two distinct genres into life during the first seven years of their career: black metal and Viking metal.

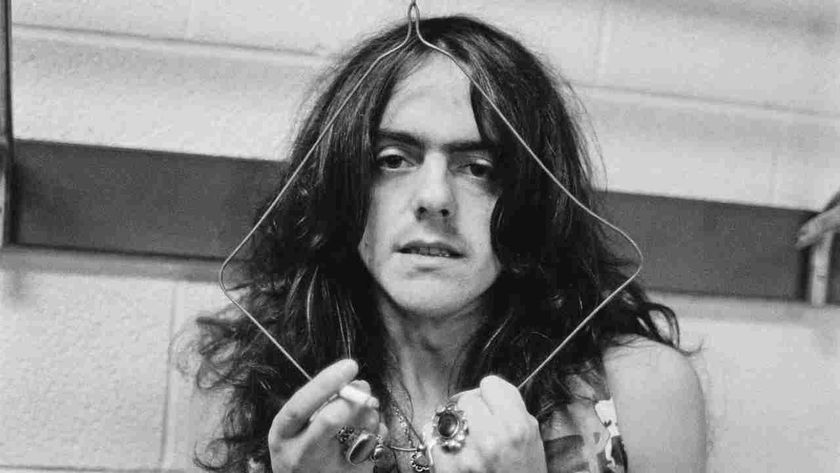

Yet by 2004, Bathory were a marginal act – not quite forgotten, but certainly overlooked by the wider metal community despite a run of six classic albums that began with 1984’s landmark self-titled debut and ended with 1991’s epic Twilight Of The Gods. This was partly down to Quorthon himself – he refused to play live, rarely did photo sessions and peppered his early interviews with obfuscation, misdirection and half-truths. In life, as in death, Thomas ‘Quorthon’ Forsberg was an enigma.

“Nobody was doing the stuff he was doing back then – he was black metal before black metal was invented,” says Watain frontman and Bathory devotee Erik Danielsson, who was introduced to the band as an 11-year-old in the early 90s by a friend’s older sister, who played him their third album, 1987’s Under The Sign Of The Black Mark. “He was such an influential musician in so many ways, but he was a conundrum even to the friends who knew him back then.”

One person who did know Quorthon was Jonas Åkerlund, the acclaimed filmmaker and video director who’s famed for his work with Metallica, Rammstein, Madonna and more. As a 17-year-old metalhead and aspirant drummer growing up in the suburbs of Stockholm, Jonas was a founder member of Bathory’s original line-up.

“Me and my cousin Frederick [Melander], who played the bass, were looking for a guitarist and a singer, so we put an advert in our local music store and he saw it,” says Jonas. “Literally the first time we met him, we saw this guy with chicken bones hanging from his neck, he had ballet tights on, kind of pink and black striped. Me and Frederick were, like, ‘Oh man, I hope it’s not that guy.’ But when we started playing, we were blown away. Ace was such an amazing musician.”

Even today, almost 40 years after they met, Jonas still calls his old friend ‘Ace’ – a nickname the teenager gave himself in honour of Ace Frehley, guitarist with his beloved Kiss (the only band Quorthon loved more than Kiss were The Beatles, whom he unironically called “the greatest thing ever to happen to the music scene”).

Jonas paints a picture of an insular but intelligent 17-year-old kid. “Ace never left the house,” he says. “Me and Frederick actually dragged him out. But he was a smart guy – he had a lot of thoughts and opinions, and he was funny too.”

Myth-making was also one of Quorthon’s many talents: he claimed to have played in a punk band in his early teens, but there’s little hard evidence to back that up. Bathory’s own beginnings have become similarly shrouded in mystery. One of the key parts of the Bathory mythology is that they played a handful of live shows in their early days, before Quorthon dispensed with the idea of performing in public entirely. According to Jonas, there’s a grain of truth in the suggestion.

“We played at an afterparty, if you want to call that a gig,” says Jonas. “And we always had people hanging out in the rehearsal studios, so we kind of did shows. But we didn’t do any official gigs.”

What the trio definitely did do was record two tracks – Sacrifice and The Return Of The Darkness And Evil – for the 1984 compilation album Scandinavian Metal Attack. Echoing the wall-of-warped-noise template laid down a few years earlier by Venom (a band Quorthon, perhaps disingenuously, claimed to never have heard at the time despite the fact they had a song called Countess Bathory), the Swedes’ gargled vocals, lower-than-lo-fi production and occult-leaning lyrics placed Bathory squarely on metal’s most extreme fringes.

Scandinavian Metal Attack was released on Tyfon Grammofon, owned by Swedish music industry veteran Börje ‘Boss’ Forsberg. Such was the secrecy that surrounded both Bathory and Quorthon himself in their early days that few were aware that Boss was Thomas Forsberg’s father. Boss set up a subsidiary label, Black Mark, especially for his son, that would release every Bathory album until Quorthon’s death, with both Forsbergs co-producing each one.

“Boss was a big influence on Quorthon’s career,” says Mark Ruffneck, vocalist with the Finnish band Oz, who appeared on Scandinavian Metal Attack, and one-time lodger at the Forsbergs’ apartment. “He put out the Bathory records when no one else probably would have.”

By the time Bathory’s self-titled debut album was released in October 1984, Jonas Åkerlund and Frederick Melander had left the band. “I wasn’t that good a drummer,” says Jonas with a laugh. According to Quorthon, the album itself was recorded in 36 hours for 2,000 Swedish Krona – less than £200. It caused minor ripples in the handful of metal magazines that existed at the time, though in those pre-necro times, most found the raw extremity of tracks such as Hades and Necromansy comic. It wouldn’t be until years later that the brutal innovation of Bathory and its follow-ups The Return…… and Under The Sign Of The Black Mark would be recognised.

“There was a raw, Satanic darkness to them,” says Watain’s Erik Danielsson. “Those records will always be there in the fundament of the black metal genre. They are so important.”

Ironically, Quorthon himself expressed little interest in the bands he had influenced. “Ace never really liked the Norwegian black metal scene,” says Jonas Åkerlund, who stayed in contact with his old friend long after he left Bathory. “He didn’t like the idea of not being able to separate the fantasy from the reality.”

Those early albums credited various bassists and drummers, though Quorthon was cagey in interviews about who else was actually in the band, sometimes alluding to other musicians, sometimes deflecting the question. Jonas believes his old friend took care of pretty much everything himself.

“This is my take on it: I don’t think there was ever any other musician in Bathory,” he says. “I know they took a few pictures early on – one of the people is actually Quorthon’s brother – and there were a couple of guys hanging round. But it was always Ace.”

By 1985, Quorthon was already shunning the sound he’d helped create and his teenage interest in Satanism, subsequently telling journalists that he had started listening to nothing but classical music. It may have been another yarn spun to keep himself entertained, but by 1988’s Blood Fire Death album, Bathory were beginning to change, bringing in elements of what would be known today as Viking metal. It was a concept Quorthon would develop on 1990’s Hammerheart and 1991’s Twilight Of The Gods.

“People talk about ‘Viking metal’, but we don’t really know what Viking music sounded like,” says Enslaved frontman Ivar Bjørnson. “For me, Hammerheart is the ultimate sound of that – it’s so raw and at the same time so melodic and beautiful. It’s all-encompassing.”

For all Bathory’s later influence, their albums barely registered outside the metal underground, even as the black metal scene that had been so inspired by Bathory began its march to notoriety. Perversely, while he was being held up as the scene’s founding father, Quorthon himself was changing musical lanes: 1994’s Requiem and 1995’s Octagon were mid-paced thrash albums that felt several years behind the curve, while a pair of solo records completely threw what remained of Bathory’s fanbase for a loop – 1994’s Album nodded towards Quorthon’s love of glam, while 1997’s Purity Of Essence was even more bizarre, bearing the imprint of both grunge and Britpop (widely scorned at the time, it features some tremendous songs).

“I can’t say I enjoyed those albums musically,” says Watain’s Erik Danielsson, “but they underline what a creative and single-minded person he was. I get the impression that a lot of things he did were on a whim, they weren’t calculated. He did what he enjoyed and did it from his heart.”

By the new millennium, Bathory had begun edging back to more familiar ground. Where 2001’s Destroyer Of Worlds was a halfway house between their mid-90s thrash sound and the Viking metal of half a decade earlier, the Nordland I and II albums from 2002 and 2003 fully embraced the latter style, albeit with a souped-up production.

It would be nice to say that Bathory were experiencing a career resurgence by the time of Quorthon’s death in 2004, but that would be inaccurate. That run of early albums remained cult favourites among the extreme metal faithful, and their name appeared on the t-shirts of more clued-up metal fans, but Bathory were largely ignored by the mainstream metal press, Metal Hammer included.

Quorthon himself seemed blasé about the situation. In 1995, he spoke to future Sunn O))) mastermind Stephen O’Malley for the latter’s fanzine, Descent. “Bathory won’t be around in 10 years from now,” he said prophetically. “I can’t tell you when the end will come… It could be possible that I decide to end it next month or in five years from now.”

In the end, the decision was taken out of his hands. His death in 2004 put a full stop on the career of this most singular of musicians, simultaneously preserving the enigma that he’d built up around himself. In subsequent years, the broader metal community has begun to acknowledge Bathory’s importance and influence. In 2010, Watain played a six-song Bathory set at the Sweden Rock Festival, introduced by ‘Boss’ Forsberg, carrying a flaming torch.

“We saw it as an opportunity to give people a bit of a history lesson,” says Erik Danielsson. “There was still no real understanding of Quorthon’s legacy in Sweden at that time. We were inspired by his vision in general, so it was fitting. And on top of everything Boss agreed to introduce the show. It gives me goosebumps just thinking about it.” (Boss himself died in 2017).

Jonas Åkerlund stayed in contact with Quorthon long after he left Bathory to pursue film- making – he says one of his big regrets was never making a video for them, despite the pair talking about it.

“Ace never cared about the size of his career, it was all about the creativity,” he says. “And creatively, he had so much more to give. There was no stopping that guy. I wish that’s one of the things I could tell him now: ‘Dude, you’re fucking brilliant.’”