It’s July 1969 and the Singer Bowl is going crazy. Originally built for the 1964 New York World’s Fair, the open-air stadium in Flushing Meadows has previously played host to The Doors, Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin and The Who. But it’s never seen anything quite like this.

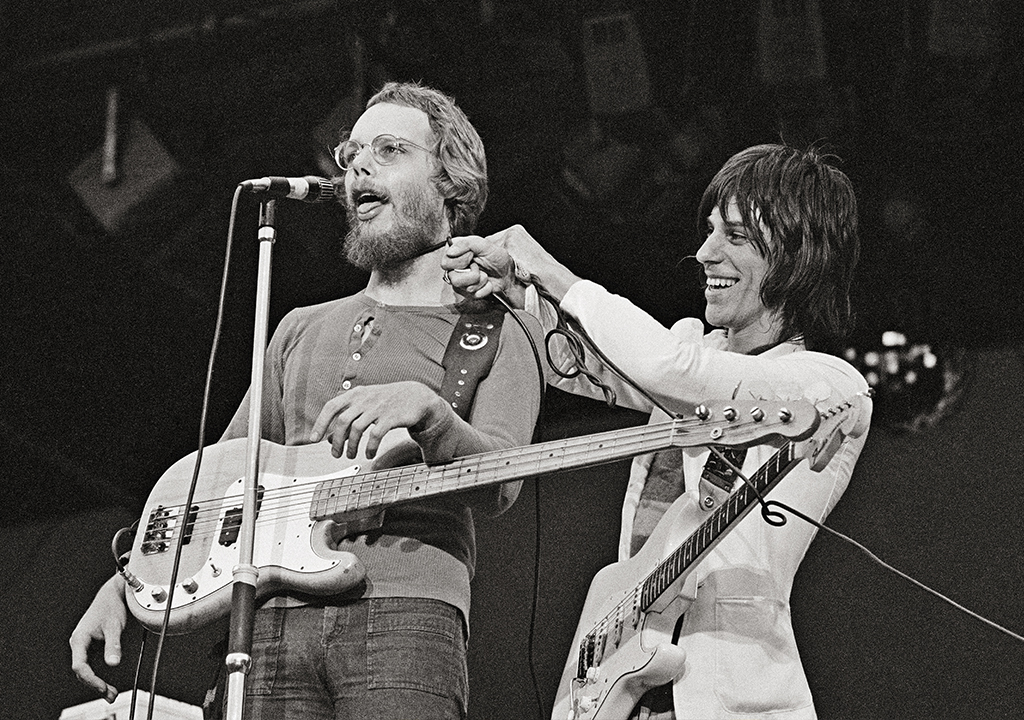

On stage, in various states of disrepair, are members of the Jeff Beck Group, Led Zeppelin, Ten Years After and Jethro Tull. Beck’s band are due to make way for the night’s headliners, Vanilla Fudge, but an encore of Jailhouse Rock has turned into an impromptu jam featuring Beck, Rod Stewart, Ronnie Wood, Robert Plant, Jimmy Page, John Bonham and more.

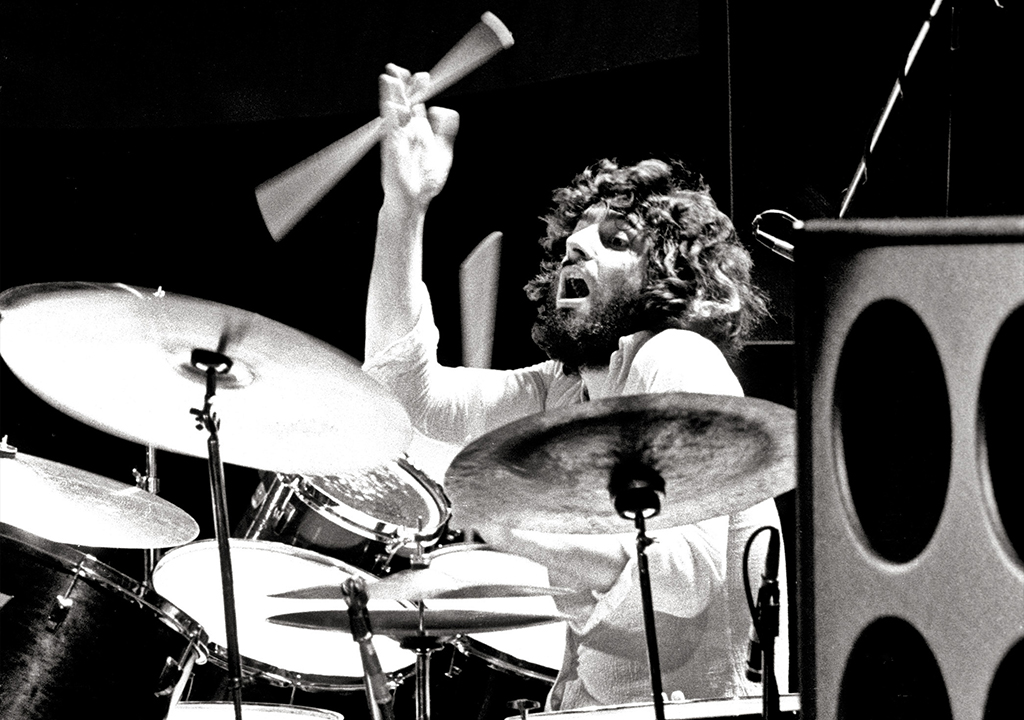

Things swiftly get out of control. A hopelessly inebriated Bonham beats out the steady rhythm of The Stripper, at which point he begins to peel off his clothes. Before long he’s stark-bollock naked. Stewart, clowning around with a mic stand, pretends to shove it up Bonham’s arse.

The local cops are getting ready to storm the place and start making arrests. Zeppelin’s manager, the estimable Peter Grant, has seen them circling and orders the lights to be killed. He and Led Zep tour manager Richard Cole dive over to Bonham and drag him off stage in the murk, by which time the drummer has passed out. Somehow they all get away with it.

Predictably, Bonham’s striptease made the headlines the next day. But his other contribution that evening, once he’d sobered up, was far more significant, at least when it came to the future of Anglo-American hard rock.

“Later on, John came up to me and [Vanilla Fudge bassist] Tim Bogert,” Fudge drummer Carmine Appice recalls, “and he said: ‘Jeff wants to put a band together with the two of you. Here’s his phone number.’”

It was a simple act of mediation from Bonham, but one that was to ignite one of the most incendiary trios in 70s rock. Beck, Bogert, Appice brought the kind of power, intensity and unbridled musicianship not heard since the heyday of Cream. Loud as damnation and bursting with experimental zeal, they bridged the gap between the psychedelic age and a nebulous new era where metal, hard funk, soul and heavy blues could all co-exist in one glorious tumult.

“People thought we were as good as it gets,” Bogert remembers. “At the time, I did too. I thought this was going to be the best thing that ever happened to me. And for a short period of time it was.”

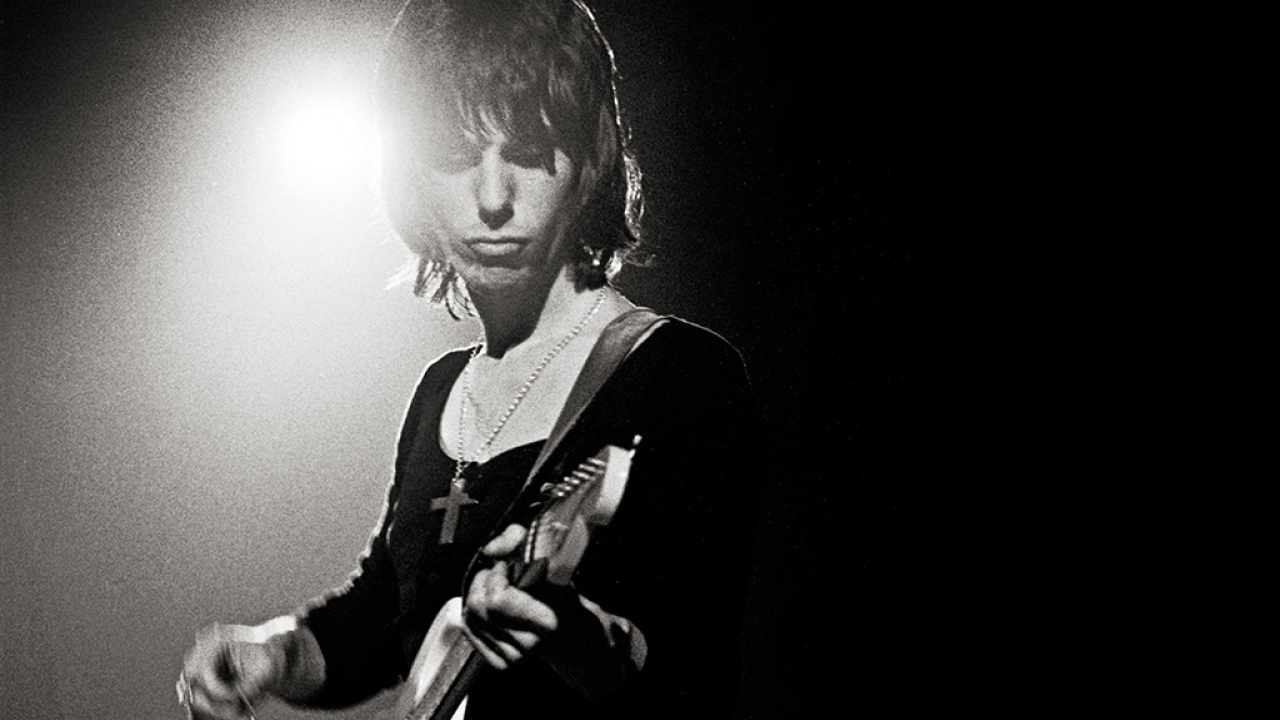

The courtship of Beck, Bogert and Appice was, to put it mildly, a protracted one. Beck had first seen Vanilla Fudge play in October 1967, following an eventful 12 months in which he’d been booted out of The Yardbirds, started the Jeff Beck Group and had a major solo hit with Hi Ho Silver Lining.

“I saw them at the Speakeasy,” Beck recalls. “They were playing at stadium-level volume in this dungeon of a club in Margaret Street. I couldn’t believe how powerful they sounded, with a Hammond organ and a double kit of Ludwig drums. Carmine was amazing and Tim’s bass was outrageous. I loved the first Fudge album, too.”

Appice remembers the occasion well. “We were so fucking powerful,” he says. “Our arrangements would just blow people away. Everybody was there that night: The Beatles, the Stones, the guys from Traffic. I remember hanging out with Jim Capaldi, Mitch Mitchell and Keith Moon, who came over to check out my bass drum. And of course we met Jeff for the first time. We were these totally American, outgoing New Yorkers – some people thought we were obnoxious – and Jeff was very reserved, very quiet.”

It turned out to be a mutual attraction. Bogert and Appice were big Yardbirds fans (especially the Beck model), and over the coming months the three of them had the occasional jam at the Speakeasy. So when Fudge guitarist Vince Martell fell ill just before the band were to record a Coca-Cola commercial for US radio at the back end of ’68, Beck seemed like an ideal substitute.

“He was unbelievable,” Appice says. “And that left an impression on us. The Fudge album we were working on at the time was Near The Beginning, and when it came out [February 1969] Jeff just loved our version of Junior Walker’s Shotgun. He thought it was the shit. There weren’t a lot of white guys playing like we did – totally heavy-duty R&B blues rock, with overtones of what was to become jazz rock.”

Despite this musical flirtatiousness, no one was making the first move. It was finally left to John Bonham to play cupid. “After John gave us the number, we called Jeff and talked about getting a supergroup together,” Appice explains. “At the end of sixty-nine you had Blind Faith, plus Leslie West was about to get together with Jack Bruce and Corky Laing. So that’s what our plan was. It was going to be Rod Stewart, Jeff, me and Tim. After a while Rod bowed out because he and Jeff had some financial difficulties. And by the time the Jeff Beck Group split up the two of them hated each other.”

The stage was set for Beck, Bogert, Appice. But they hit a major snag before they even began. In November 1969 Beck was driving his hot rod when he was involved in a head-on collision with another vehicle that left him with a fractured skull. All immediate plans were put on hold.

It was nearly three years before the trio finally got it together. In the wake of Vanilla Fudge’s demise in 1969, Bogert and Appice formed the blues rock combo Cactus. Beck, meanwhile, had resurrected the Jeff Beck Group with an entirely new line-up.

Eager to avoid the pitfalls that befell much-hyped supergroups like Blind Faith, Bogert and Appice decided to assimilate themselves gradually. While touring with Cactus they would often sit in with the Jeff Beck Group on stage. “Carmine and I enjoyed that very much,” says Bogert. “Then the three of us went over to England to rehearse for an album and tour. We kept throwing ideas out. It was a spontaneous jam that became songs.”

In December ’72, Beck, Bogert, Appice went into to Chicago’s Chess Studios to record their first album. “With it being a trio, me and Tim decided to sing,” Appice says. “In those days it wasn’t so much about the songs, it was more about the playing. The songs were just vehicles for us to jam.”

One of the most striking songs to emerge was Superstition. Stevie Wonder, a long-time admirer of Beck, had invited him to play on the sessions for his Talking Book album. Beck readily agreed, with the stipulation that Wonder write him a song. The guitarist apparently helped out with the rhythm and some of the lyrics to Superstition, Wonder’s uptempo funk monster, and they recorded a demo in New York. The song was initially intended for BBA, but problems started when Berry Gordy, the boss of Wonder’s label, Motown, heard it. Convinced it would be a huge hit (rightly, as it transpired), Gordy insisted that Wonder recut the song and release it himself. BBA were left to do their own version instead, months later.

“Stevie wrote Superstition specifically for a trio,” asserts Beck. That song was custom-made for me as part of a three-piece. Our version was seriously metal for the time, though Stevie hated it with such a vengeance that you could almost taste it.”

BBA’s Superstition was a tour de force, from its clanging intro to Appice’s tornado drums to Beck’s ferocious rhythm licks. “Jeff wanted it to be more ballsy, not so R&B kind of wimpy,” Appice recalls. “When we did it we slowed it down a little, like we used to do with Vanilla Fudge, and it was really soulful and powerful.”

There were other mighty moments in the BBA locker, not least the complex Lady, all three bandmates with full heads of steam, and the eloquent soul stirring of Sweet Sweet Surrender. The latter was one of two tunes written by the album’s producer, Don Nix. His other was Black Cat Moan, an evil blues number with squealing slide runs and driving bass. The sessions themselves, however, were difficult. Chess, with their archaic studio gear, were not suited to a band who prided themselves on the subtleties of dynamics. “It was very problematic,” Bogert remembers. “Things were breaking down and the studio was falling apart at the seams. Suddenly everything would stop in the middle of a take. It was just awful. Then everybody’s nerves got on edge. When you have three temperamental artists in that state, nothing good ever happens.”

Beck, Bogert, Appice was released in the spring of 1973, whereupon it rose to No.12 in the US Billboard chart and dipped into the Top 30 in the UK. Finishing the album in LA had brightened the mood, but it was already evident that BBA’s issues were more deep-seated.

“When the album came out we started to tour, and the band turned into factions,” says Bogert. “It wasn’t the fun I hoped it was going to be. The thrill of it all had been so wonderful in the beginning, but then there were personality conflicts and things went downhill quickly.”

Appice soon found himself cast in the role of conciliator. “Jeff has always been known to be moody,” he explains. “Sometimes he’d just not want to talk to anybody. Which was something that Tim didn’t understand, because he was so outgoing, almost on the verge of craziness. The way Tim played bass was the way he was as a person. He just didn’t like taking shit. So there was a bit of a clash, and I was the guy in the middle who weighed both sides and tried to keep the peace.”

For his part, Beck places the blame on BBA’s management situation, an unsteady Anglo-American axis of Ernest Chapman and Phil Basille: “There was a lot of greed on the management side. They were constantly at each other’s throats about the money, and I knew it wasn’t going to last.” Bogert remembers Basille as “a low-level Mafia guy who thought he was in control. The word ‘clusterfuck’ comes to mind immediately.”

This recollection is intended in good spirits, which is in contrast to the final days of BBA. In fact come the end of 1973 there wasn’t a great deal of humour to be found at all. Especially when Beck took off in the middle of a major tour.

“We were flying high, selling out big venues everywhere, playing to ten thousand people all over the world,” says Appice. “We were on tour in America, somewhere in the south, and our tour manager came up to Tim and I at breakfast. He just said: ‘Tonight’s gig is off. Jeff went home.’ We couldn’t believe it. We still had another five sold-out gigs coming up. I never really got the full story. But all that left a bad taste, especially with Tim. He was real pissed about that.”

The three of them attempted to patch things up back in England, where they tried recording a second LP. Appice says the sessions were blighted by lack of inspiration and a lingering, “weird vibe” from Beck’s US tour bail-out. They played dates in Europe, followed by another stab at recording a studio album, before management resolved to bring in a major-name producer, Jimmy Miller, for a third attempt.

Turmoil notwithstanding, the trio were big business, playing to sell-out venues at home and abroad. In May ’73 BBA performed two triumphant shows at the Koseinenkin Hall in Osaka, Japan. The Far East had long been a stronghold, dating back to their respective histories in The Yardbirds and Vanilla Fudge. From those shows came the album Live, released later that year in Japan only. “We were the first band to sell out the Budokan in Tokyo,” Appice says. “The Japanese audiences were crazy for us. Fans would be waiting at the airpor.”

Ever eager to dodge the issue of singing (and none of BBA were great vocalists), Beck showcased a new toy on Live: the talkbox. “I’d heard Stevie Wonder use it,” he says. “And before that there was a guy called Mike Pinera [of Blues Image, Iron Butterfly and Ramatam fame]. I saw him play and thought this was the most amazing thing. He said: ‘Here, man. I don’t use this any more,’ and he gave it to me. My first critique read: ‘Jeff Beck has a throat problem. He can’t use his voice, so he had to sing with a medical aid.’ Then Peter Frampton nicked the whole thing – lock, stock and barrel.”

BBA recorded an album with Miller at CBS in London, but the band couldn’t quite agree on it. “We were looking for more of a composer/producer, somebody who was hands-on,” Beck exlains. “Because the talent was there, but we just needed guidance. The frustration of trying to forge new material for a trio isn’t easy. It has to be blues-based, white rock-based, and I was not going there. I did not want to be like Cream, too bluesy. I just thought we’d run out of steam.”

Things finally came to a head – in dramatic fashion – before a gig at the Rainbow in London in January ’74, on the last night of a UK tour.

“I had pneumonia that night, and had had it up to my eyebrows,” explains Bogert. “I wanted a ham and cheese sandwich before the gig, because my stomach was so off. They had this huge macrobiotic meal laid out for Jeff, but there was nothing there that Carmine and I ate. I walked in and said something like: ‘Oh, Jesus!’ Then Jeff got in my face and I threw a punch. I just thought: ‘Fuck this!’ It wasn’t cool of me to do that, but when you’re feeling lousy and you’re stressed and tired you do foolish things.”

BBA played the gig – recorded for broadcast on US radio show Rock Around The World – but they were done. “Rod Stewart had told me long ago, regarding Jeff: ‘Don’t do it. You’ll do an album or two and then it’ll be over,’” recalls Appice. “But we didn’t listen to that advice. But that’s what happened. It ended up a mess at the end.”

Today, all three parties are politic when it comes to BBA’s fleeting lifespan. “The live gigs were utterly electrifying,” offers Beck, whose first post-BBA project was a solo album, Blow By Blow. “I loved them both, and it was a great experience. But I think those things are best short-lived, a quick blast up the road and then forget it.”

Bogert insists it’s all water that has long passed under the bridge. In fact, he says, he’d welcome the opportunity to play with Beck and Appice again: “We’re old men now, so all of that young craziness is gone.”

Appice, however, is a little more wistful. “I wish it would’ve lasted longer,” he muses. “I don’t think we ever reached our potential. If we’d done another album and world tour, which is what the deal originally was, we would’ve been really big. I think we would’ve been a household name.”