"The psychedelic scene was largely over by the summer of 1968, but that spirit of musical adventure was still running rampant": A beginners' guide to the origins of prog rock

Where on earth did progressive rock come from?

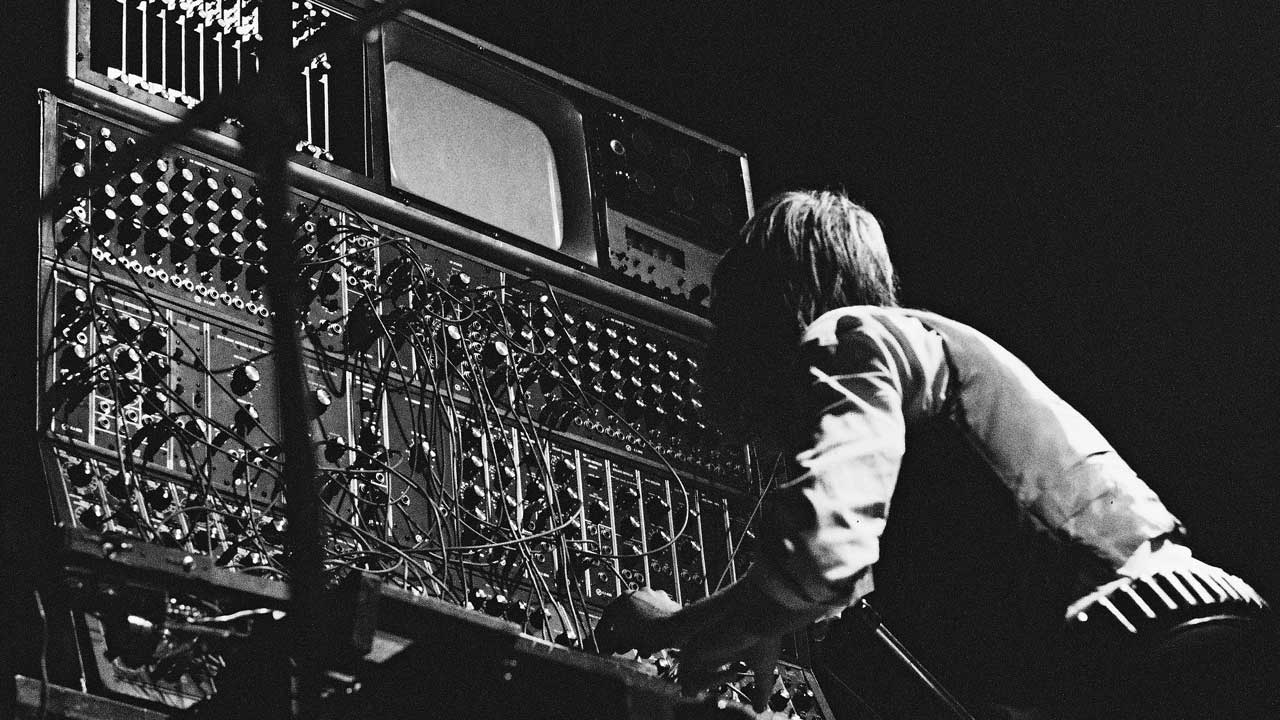

The origins of progressive rock are inextricably bound up with the seismic changes in the British music scene that took place in the mid-60s, when bands that had hitherto forged their reputations playing American rock’n’roll, R&B, blues and soul began writing their own songs. Almost as significant was the advance in music instrument (in particular, keyboards) and equipment technology that increased the range of sounds available to add to the mix. To begin with, however, this technology was mainly confined to the recording studio.

In 1967 The Beatles were also confined to the recording studio, having given up trying to play concerts that neither they nor their audience could hear. It’s difficult to convey the impact that The Beatles’ Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band album had on the whole music scene when it was released in June that year. Put simply, nobody had heard anything like it before.

It wasn’t just the sounds – the bursts of fairground organ, sitar or brass band – that was ground-breaking for a so-called ‘pop’ album, it was the whole construction of Sgt Pepper… that stirred the imagination: the way the songs segued into one another; the refrain of the opening title track near the end; the final orchestral cacophony at the climax of A Day In The Life followed by a single piano chord that gradually died away.

Before Sgt Pepper…, albums had consisted of a dozen or so songs, and while some care might be taken over the sequence you could play any track in isolation. Sgt Pepper… was designed to be played from start to finish, not least because the segues made it very difficult to cue up any individual song on the vinyl record.

It was also impossible to imagine The Beatles being able to play the album live. The technology was not yet available to recreate most of those sounds on stage; The Beatles had been pushing the limits of technology to make many of those sounds in the studio. Nowadays, of course, you could programme within minutes a keyboard to play each and every sound.

While the Beatles were recording Sgt Pepper… at London’s Abbey Road studios, Pink Floyd were down the hall recording their debut album, Piper At The Gates Of Dawn, which came out in August 1967.

Unlike Sgt Pepper… which had been made for the mass market, Piper At The Gates Of Dawn was aimed specifically at the burgeoning underground counter-culture. The melodies were camouflaged by discordant, avant-garde sounds that baffled the ordinary pop music fan. What’s more, Pink Floyd were able to reproduce their album on stage. They weren’t so much pushing the boundaries of technology as pushing the boundaries of pop music. One thing that both Sgt Pepper… and Piper At The Gates Of Dawn had in common, though, was that no singles were released from either album. It was another sign of the changing times.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Three months later came the Moody Blues’ Days Of Future Passed, an album that not only introduced the Mellotron – perhaps the most important instrument in the development of prog rock – but was also deliberately conceptual, with a series of songs that spanned a day in the life, from morning until night.

The Who also themed their third album, The Who Sell Out, in late 1967, effectively turning the record into a pirate radio broadcast with spoof advertisements between the tracks.

Meanwhile the technical possibilities of the keyboard were being explored in two other albums released in December 1967: The Nice’s The Thoughts Of Emerlist Davjack and Traffic’s Dear Mr Fantasy. It helped, of course, that both bands’ keyboard players – Keith Emerson and Steve Winwood respectively – were virtuosos.

The underground scene offered the best opportunity for bands to experiment with sounds and concepts in front of a sympathetic audience. Pink Floyd’s second album, A Saucerful Of Secrets, released soon after the departure of madcap genius Syd Barrett in the summer of 1968, was hailed as a psychedelic masterpiece, but the title track was a carefully constructed 12-minute epic in three movements, that had clearly progressed from the summer of love a year earlier.

Arthur Brown was another underground favourite, and although he was mainly influenced by American R&B acts like James Brown and Screaming Jay Hawkins the first side of his debut album, The Crazy World Of Arthur Brown (produced by Pete Townshend), was a continuous segue of songs and poetry. More significantly there was no guitarist in the band, just the swirling organ of the classically trained Vincent Crane (who would soon move on to form Atomic Rooster).

If the psychedelic scene was largely over by the summer of 1968, the spirit of musical adventure it had unleashed was still running rampant. Procol Harum, whose A Whiter Shade Of Pale had been the soundtrack for the summer of 1967, allocated the whole of the second side of their Shine On Brightly album in 1968 to the sprawling In Held Twas In I, a suite of songs with a recurring motif.

Family, a Leicester band who’d built their reputation on the strength of their live shows and the rasping vocals of Roger Chapman, revealed a sophisticated musical sense on their debut album Music In A Dolls House, reprising musical themes from their songs in between the tracks.

Unnoticed amid the barrage of albums that summer was The Cheerful Insanity Of Giles, Giles & Fripp. A Bournemouth trio consisting of Peter and Michael Giles on bass and drums with Robert Fripp on guitar, the album was as wacky as the title suggests, each side featuring a musical story – The Saga Of Rodney Toady and Just George – which was alternately whimsical and cringeworthy. Soon afterwards the trio were joined by keyboard and woodwind player Ian MacDonald and lyricist/ roadie Pete Sinfield. When Peter Giles left towards the end of the year he was replaced by Greg Lake and the band was renamed King Crimson.

King Crimson had three shots at recording an album before they were satisfied. In The Court Of The Crimson King was released in October 1969 and is widely regarded as the first progressive rock album – a term, incidentally, that Robert Fripp has always detested.

The previous six months had seen debut albums from Genesis (From Genesis To Revelation), Yes (Yes) and Van Der Graaf Generator (Aerosol Grey Machine), three bands who would within just a couple of years become synonymous with prog rock.

Genesis keyboard player Tony Banks remembers getting his first Mellotron in 1971 before the band recorded Nursery Cryme: “It was King Crimson’s third Mellotron. I went round to collect it, and even their roadie seemed ‘big time’ to me. I felt really self-conscious playing it. The first thing I used on it was the string sound for a song which became The Fountain Of Salmacis.”

As for King Crimson themselves, they would never make another album like In The Court Of The Crimson King, but the legacy would live on, musically and figuratively.

Hugh Fielder has been writing about music for 50 years. Actually 61 if you include the essay he wrote about the Rolling Stones in exchange for taking time off school to see them at the Ipswich Gaumont in 1964. He was news editor of Sounds magazine from 1975 to 1992 and editor of Tower Records Top magazine from 1992 to 2001. Since then he has been freelance. He has interviewed the great, the good and the not so good and written books about some of them. His favourite possession is a piece of columnar basalt he brought back from Iceland.