They say you should always leave the audience wanting more. Mike Ratledge, who died yesterday aged 81, did exactly that. In the 49 years since he left Soft Machine, somebody, somewhere would be commenting that they would love to see Ratledge play live with the Softs ‘one more time’ or perennially asking what he was up to in letters to music magazines and later, in the message boards and fan forums of the internet.

Decades after the urbane, softly-spoken had played his last note with the band, wherever and wherever the school of musicians who were part of the so-called ‘Canterbury Scene’ were performing, it was a certainty that after the gig curious fans would make earnest inquiries about the long-absent keyboardist. Such was their regularity, a slightly exasperated Pip Pyle, drummer with Gong, Hatfield And The North, National Health, gently lampooned the situation in the lyrics of his song, What’s Rattlin’. Recorded by Richard Sinclair in 1994 it has the classic line, 'One question we all dread, ‘What's doing Mike Ratledge?’

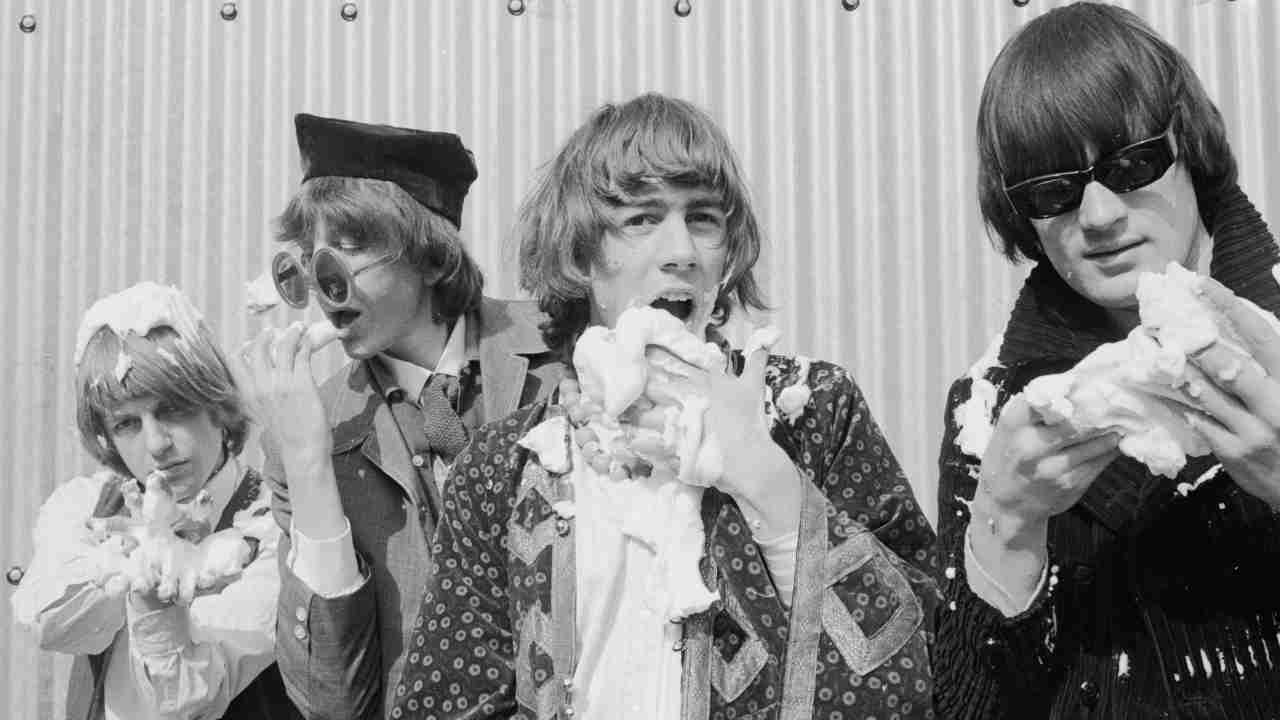

Behind those dark glasses and unsmiling visage, he presented an inscrutable presence. Seemingly aloof to whatever was happening around him on stage he was nevertheless seated at the centre of a whirlwind where his soloing would explode in a torrent of blazing, creativity that was as savage as it was eloquent. With his shoulders rising and falling as his hands jabbed, pawed, and parried at his electric piano, he exerted a magnetic kind of cool that endeared him to so many fans.

Born in 1943 and the son of a headmaster, he received a solid grounding in classical music as a child. However, his formative interests as a teenager in the early 1960s were influenced by Daevid Allen who introduced him to the rapid-fire circularities found in the playing of jazz musicians such as pianist Cecil Taylor and saxophonist John Coltrane’s ‘sheets of sound’ technique. These elements ultimately found a vivid expression in Ratledge’s late 1960s playing that fuelled The Soft Machine’s breakneck experimental pop. Having left Oxford with a degree in psychology and philosophy, he was a fervent reader of poetry and literature. His love of American fiction, particularly William Boroughs’ fourth novel, The Soft Machine would ultimately provide the name of the band for which he is best known.

Interviewed about the origins of the name to a reporter on Belgian TV in 1969, Ratledge says, “It’s a generic term for the whole of the human species. Because we’re a pop group we assume that we’re going to get through to a lot of people therefore we’re part of the soft machine. Everybody is part of the soft Machine.”

Having augmented his Lowery Holiday Deluxe organ with a fuzz pedal he fashioned a stinging sound brimming with a glowering, Hendrix-inspired distortion. Unique among his Hammond, Vox, and Farfisa-playing contemporaries Ratledge’s singular trademark timbre and legato-style soloing darted around the keyboard sounding like a homicidal wasp on the warpath. Throughout the group's history, they played as loud as their equipment would allow. His solos were forever teetering on the brink of glowering feedback as his volley of rapid phrases frayed at the edges as he raced into the upper registers.

Having toured the USA opening for Jimi Hendrix and recording their 1968 debut album in New York, Ratledge's writing for the group rapidly stretched beyond the initial psychedelic milieu surrounding the band, turning instead from the fractious pop dadaism into something more precise and cerebral on 1969's Volume Two. His accelerated writing for Soft Machine's legendary but sadly short-lived septet line-up stylistically paved the way for 1970’s Third. A landmark double album, it stands as the arrival of Soft Machine proper boasting Robert Wyatt’s Moon In June, Hugh Hopper’s Facelift and Ratledge’s Slightly All The Time, and Out-Bloody-Rageous. All absolute classics of the Canterbury genre, this latter in particular track marries Ratledge’s articulate writing with his love of Terry Riley-inspired tape-looping., something he would explore further in the proto-ambient so-called 'cosmic tinkles' of his echo-plexed Fender Rhodes piano as heard on Fifth, Six and especially Seventh.

Amidst the sound and fury of his steely, propulsive themes and frenzied soloing such as the formidable Teeth from Soft Machine’s Fourth in 1971, it’s easy to overlook the tenderness inhabiting some of his compositions. The languid organ chords that swell and ebb beneath Elton Dean’s flowing sax solo in the Backwards section of Third’s Slightly All The Time possess an aching melancholy, whose bittersweet qualities Caravan amplified on 1973’s For Girls Who Grow Plump In The Night when they adapted it as part of their L’Auberge du Sanglier suite. The diaphanous melody of Chloe And The Pirates from 1973’s Six and The Man Who Waved At Trains from Bundles in 1975 also sing and shine with a mellifluous, haunting delicacy.

During his time in Softs, he contributed distinctive guest spots on albums by Syd Barrett and Kevin Ayers, as well a truly caustic contribution to Elton Dean’s self-titled solo LP. When Mike Oldfield’s Tubular Bells was performed on BBC TV’s Full House arts show in 1973, with a cast of the great and good of the progressive music scene, the first thing viewers hear is Ratledge on grand piano playing that now-famous trickle of notes that binds the work together. Eagle-eyed Ratledge-spotters will also see him traversing the studio floor as he moves from one keyboard to another.

Leaving Soft Machine in 1976 he appeared on his friend David Bedford’s 1977 release Instructions For Angels in 1977, along with the suitably gnomic sequencer-based score to the cult film, Riddles Of The Sphinx, in the same year. His other work outside of Soft Machine included a partnership with Karl Jenkins, writing and performing advertising jingles which, somewhat bizarrely saw the pair credited as the brains behind the forensic recreation of Marvin Gaye’s I Heard It Through The Grapevine which was used in a famous TV advert for Levi 501 jeans in 1985. In the 90s Ratledge also assisted Jenkins with his Adiemus project but also spent time getting deep into tech, and even writing apps including one designed to help make a perfect boiled egg.

The abundance of posthumously released bootleg recordings of Soft Machine that have steadily flooded the market over the years goes some way to capturing the restless, fiery spirit that fuelled his playing and made it take flight. Mike Ratledge was only in Soft Machine for ten of his 81 years on the planet but he’ll be forever remembered as an innovative and energetic force within the progressive community and beyond.