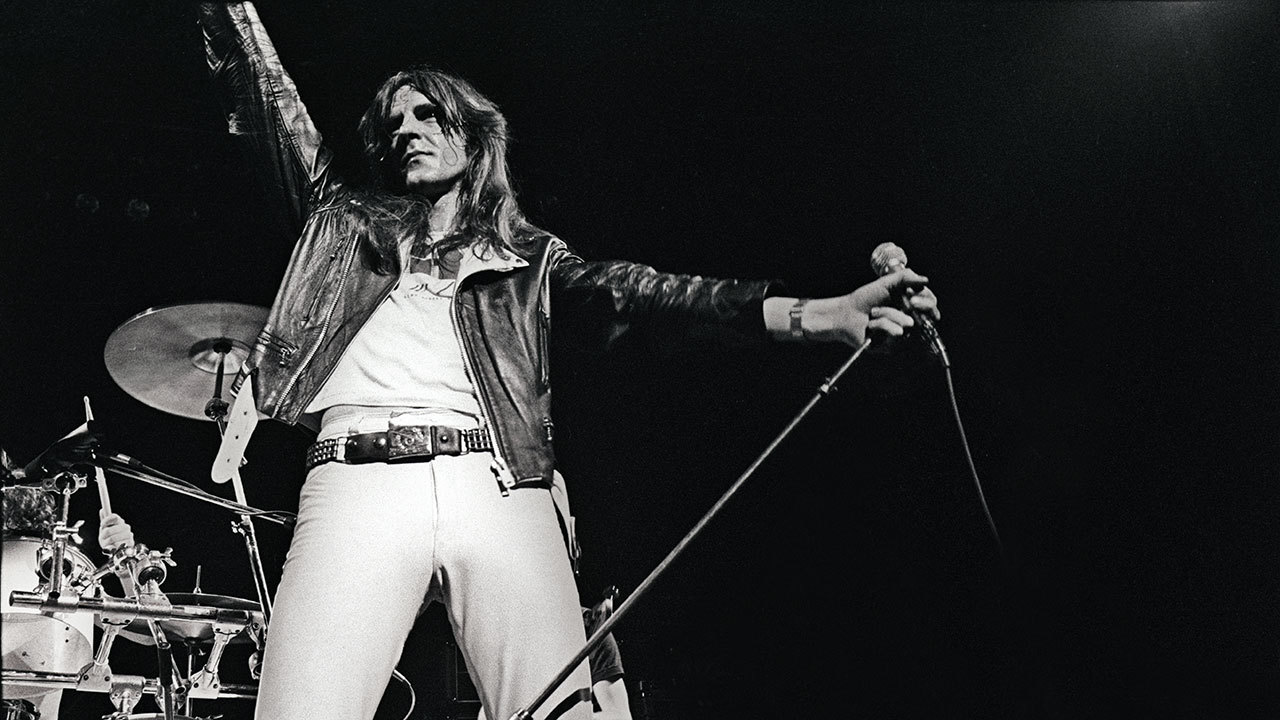

Biff Byford is on top of the world. More specifically, on top of a piano, peering out of a window and down at a line of dozens of people below him.

He and his bandmates in Saxon are holed up in a room on the second floor of the Whiskey A Go Go, the fabled Sunset Strip club that has been the launch pad for some of LA’s greatest rock bands. Tonight, March 27, 1982, it’s host to five Yorkshiremen with fire in their loins and Castrol GTX running through their veins.

Pan an imaginary camera around the room and you’ll see a scene that defines the coming decade. Over there is Saxon’s old touring buddy Ozzy Osbourne and his girlfriend Sharon Arden. Ozzy is still distraught over the death of his guitarist Randy Rhoads a couple of weeks earlier. He’s dealing with it by getting as fucked up as possible all the time. Today he’s barely coherent.

The camera swings around as the door bursts open and four hotshots with leather jackets, eye make-up and candyfloss hair tumble in. This is Mötley Crüe, the buzziest band in LA right now. They’re huge Saxon fans – especially bassist Nikki Sixx – and they’re here to meet their heroes.

Follow that same camera down the stairs and into the venue’s main room. On stage, four teenage headbangers are snarling their way through a song that sounds like a feral animal that’s been starved for weeks then let loose. They’ve been chosen by Saxon themselves to open both of today’s two shows. Their name is Metallica. God alone knows what will become of them.

For the past two years, Saxon’s career has swung faster and faster in one direction: upwards. Their last three albums – Wheels Of Steel, Strong Arm Of The Law and Denim And Leather, machine-gunned out in the space of 18 months – have been stone-cold instant classics. Back home in Britain they’re standard bearers for a new grass-roots rock movement, unlikely pop stars, bona fide working-class heroes. Here in LA they’re heavy metal crusaders, emissaries from another place bringing new sounds and new velocities that will electrify what’s happening in a town constantly looking for its next fix of excitement.

“We were big in Britain, no argument,” Biff says. “Probably the biggest of our generation of metal bands at the time. We’d done it through hard graft and killer songs; none of that trendy image rubbish.”

Los Angeles falls for Saxon, but in the end America never truly does. Maybe their music is too driven, too macho, not mellow enough. Maybe their Yorkshireness is too undiluted for Boise, Idaho and Hell, Minnesota. Maybe – with their moustaches and mix’n’match hairlines – they’re just not pretty enough.

Saxon don’t need America to rubber-stamp their greatness. Thanks to that holy triptych of albums they released at the dawn of the 1980s their immortality is enshrined. Today history might have relegated them to a distant fourth behind Iron Maiden, Def Leppard and Motörhead, but Saxon did as much to forge heavy metal’s glorious future as any of those bands.

“That band was so fucking cool,” former Mötley Crüe bassist Nikki Sixx says today. “They had all of the elements of the great British heavy metal bands – the Deep Purples and Black Sabbaths – but they also had the rawness of AC/DC and punk. They should never have been playing at the Whiskey, they should have been headlining arenas.”

The story of Saxon isn’t a glamorous one. Not compared to that of Led Zeppelin or Ozzy or Mötley Crüe, anyway. You don’t come to them for sordid tales of sex, drugs and death by gardening accident. (Well, maybe you do for sex. “We did alright on that front, thank you very much,” says Byford.)

Saxon’s tale is all about grit and determination. It’s caked in sweat, and reeks of exhaust fumes and the back rooms of Working Men’s Clubs. But it’s also a tale of heroic escape – from the council estates they lived on, from the pits and factories they worked in. It’s no coincidence that many of Saxon’s greatest songs – Motorcycle Man, Wheels Of Steel, Midnight Rider – celebrated the freedom of the open road.

“The late seventies were a wasteland,” says Byford. “Strikes, poverty, the edge of anarchy. It was a bad period. Saxon came out of that.”

Byford turns 67 this month, but he still stands as tall and rigid as an oak. The mane of hair is whiter than it is blond these days. He has no time for deep insights or touchy-feely confessionals. Impertinent or plain stupid questions are greeted with an impatient arch of the eyebrow. You can take the boy out of Yorkshire, but you can’t take Yorkshire out of the boy.

The members of Saxon lived within 10 or 15 miles of each other in the Barnsley-Sheffield-Doncaster triangle when they started out in 1976, when they still traded under the deliberately provocative name Son Of A Bitch. All five – Byford, guitarists Graham Oliver and Paul Quinn, bassist Steve Dawson and drummer Pete Gill – had plenty of miles on the clock in other bands, but this one was different.

“We had all these plans to take over the world,” says original bassist Dawson. “We were five lads together all the time. There was no weak link. No one were saying: ‘I can’t play a gig this weekend because me missus won’t let me’ and all that malarkey.”

“We all had various jobs at different times, but we got the sack because we wouldn’t turn in for work or we’d get there late,” says Oliver. “You’d run out of petrol on the way back from Hull and you’d have to wait until the next morning to get home.”

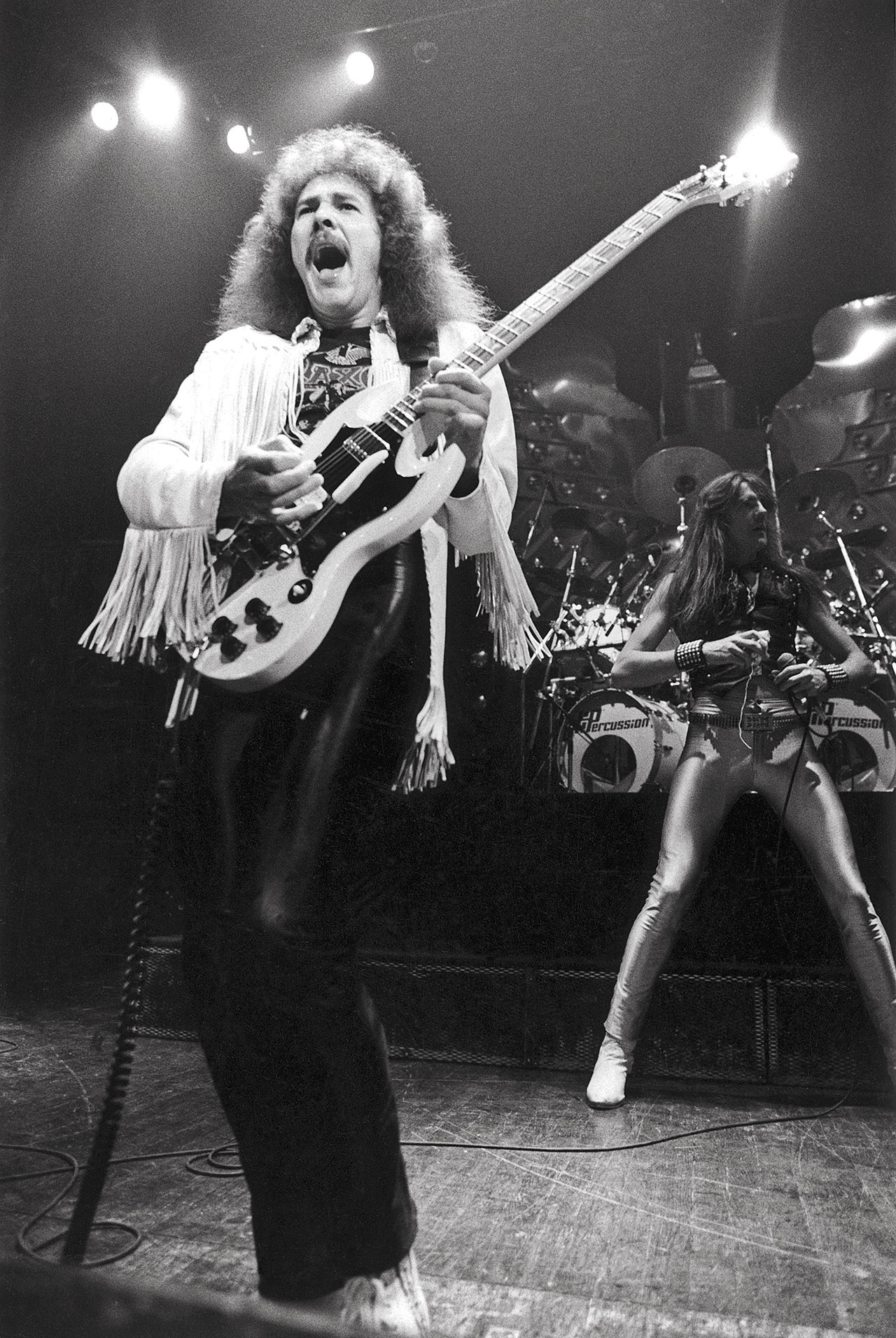

For anyone listening to Saxon’s music at the time, Oliver and Dawson were as important to the Saxon sound as Byford’s colliery siren voice. The former was half of one of the era’s great guitar teams, up there with Gorham and Robertson or Tipton and Downing. Dawson was Saxon’s engine room, a bare-chested dynamo wearing a denim jacket and moustache (something actor Harry Shearer borrowed a few years later when he created Spinal Tap bassist Derek Smalls).

In their early years, Son Of A Bitch/Saxon burned though gallons of petrol gigging up and down the country, riling venue owners by refusing to play covers of the day’s pop songs. They drove a battered American car, an Oldsmobile Cutlass, imported by a friend of theirs, partly because it looked cool and partly because it had a bench front seat and could fit everyone in comfortably. They played anywhere that would have them, with anyone who would have them: the Ian Gillan Band, Heavy Metal Kids, Woody Woodmansey’s U-Boat, Nutz. At one point they opened for The Clash. Byford: “It was only one gig, in a place called Belle Vue in Manchester. I only remember it cos it was a really odd bill. People were spitting at us. That was showing their appreciation, so we obviously went down well. We did a festival with Joe Strummer years later and he fucking remembered it. I was really impressed. We were jamming 747 with an acoustic with him.”

Saxon didn’t see punk as an obstacle so much as an inspiration. They shared DNA: speed, rawness, a fuck-you attitude. Biff Byford was a street rat just like Johnny Rotten, only those streets happened to be in Barnsley rather than North London.

“One of our first appearances at the Marquee, Pete Gill accidentally knocked over his drum kit and it cut my hand,” says Oliver. “There was blood all over. I remember one guy at the front shouting, ‘This is great, it’s just like punk!’”

Like the punks, Saxon looked as if they’d stepped out of their own audience and on to the stage. They sounded like it too. Not for them the last-days-of-empire excess of mid-70s Zeppelin or the musical showboating of the prog crowd. The song titles said it all: Backs To the Wall, Still Fit To Boogie, Stallions Of The Highway…

A deal with Queen’s former managers, Trident, got them a wage of £30 a week, which they spent on leather jackets, jeans and petrol. French disco label Carrere signed them for £50,000. For five working-class guys it was like winning the Lottery.

“They got lucky, didn’t they?” Byford says bluntly. “They found a stinking rock band and we sold a lot of records for them. They were in the right place at the right time with the right money.”

Things got off to a rocky start, however, with Carrere hating the original mix of Saxon’s self-titled debut album.

“We’d never been in a studio,” says Oliver. “We’d got these people who worked with Queen watching over our shoulder, and they’d got an idea of how they wanted us to sound. It weren’t us. It were too slick.”

The band went back to the rawer demos they’d recorded a few months earlier and gave them a bit of spit and polish. The finished album was a patchwork of styles – bell-bottomed hard rock, tough-as-leather heavy metal, a shot of the blues, a whiff of psychedelia – but at least it was pointing in the right direction.

The public voted with their wallets – which remained in their pockets, unopened. Trident were even less impressed and dropped the band, putting them back on the dole. But Saxon were made of strong stuff. As Biff sang prophetically on Backs To The Wall: ‘My hopes shot down, my backs to the wall/But I’ve got my pride, they can’t take it all.’

There’s a great film to be made about the late-70s rock scene. Or maybe it’s a sitcom. Either way, it’s set entirely in an imaginary service station on the M1 in the early hours of the morning sometime in 1979. Saxon stride purposefully past shuttered Wimpy Bars and unplugged Space Invaders machines, nodding to members of Iron Maiden, Def Leppard and Angel Witch as they slurp cold tea in an attempt to keep themselves awake on their journey to or from their latest gig in some godforsaken part of the country.

Saxon played with most of those bands. At the end of 1979 they headlined a prestigious gig at London’s Music Machine, supported by Iron Maiden. Within 12 months this nascent scene would be christened the New Wave Of British Heavy Metal. “Were there rivalries? No,” says Byford. “We didn’t give a shit. We just used to go on and try and destroy everything.”

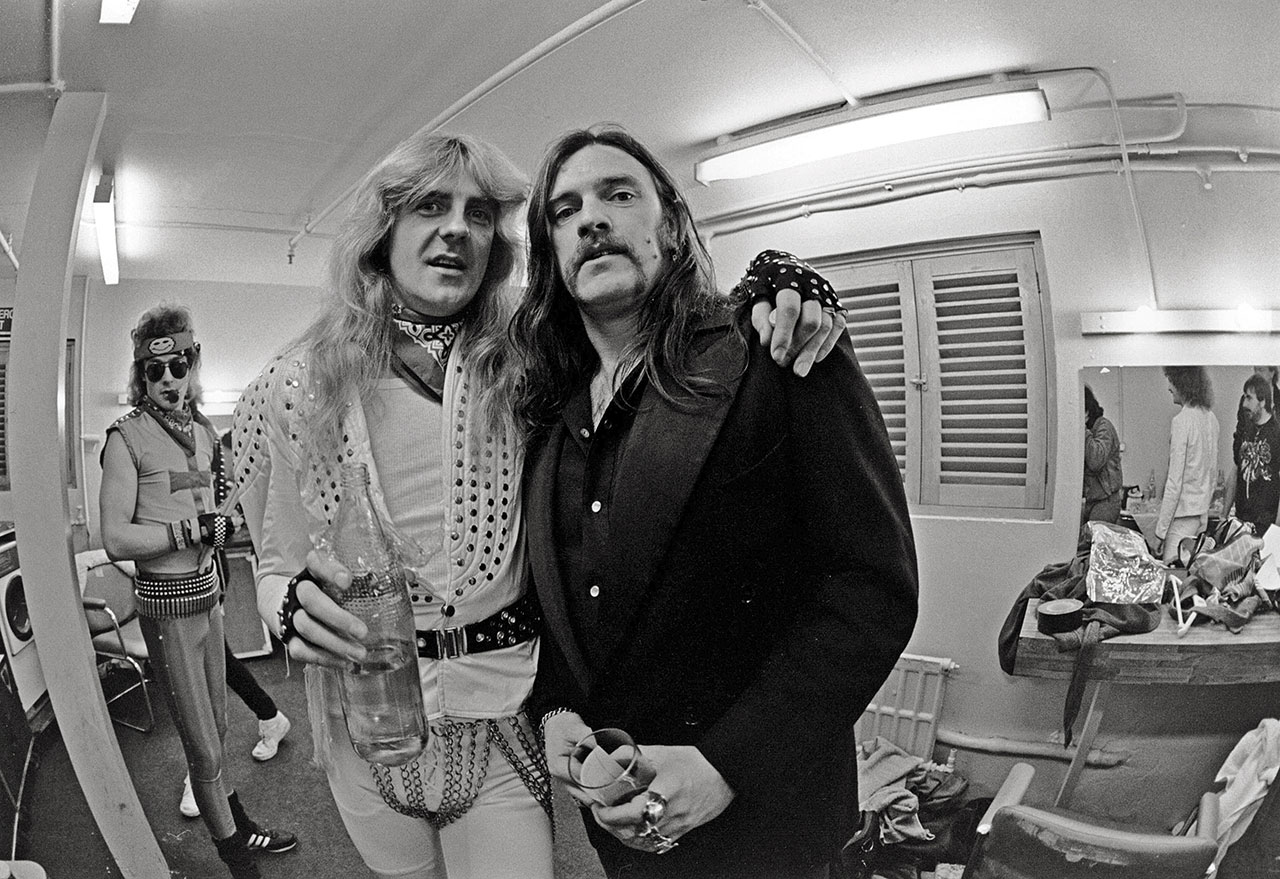

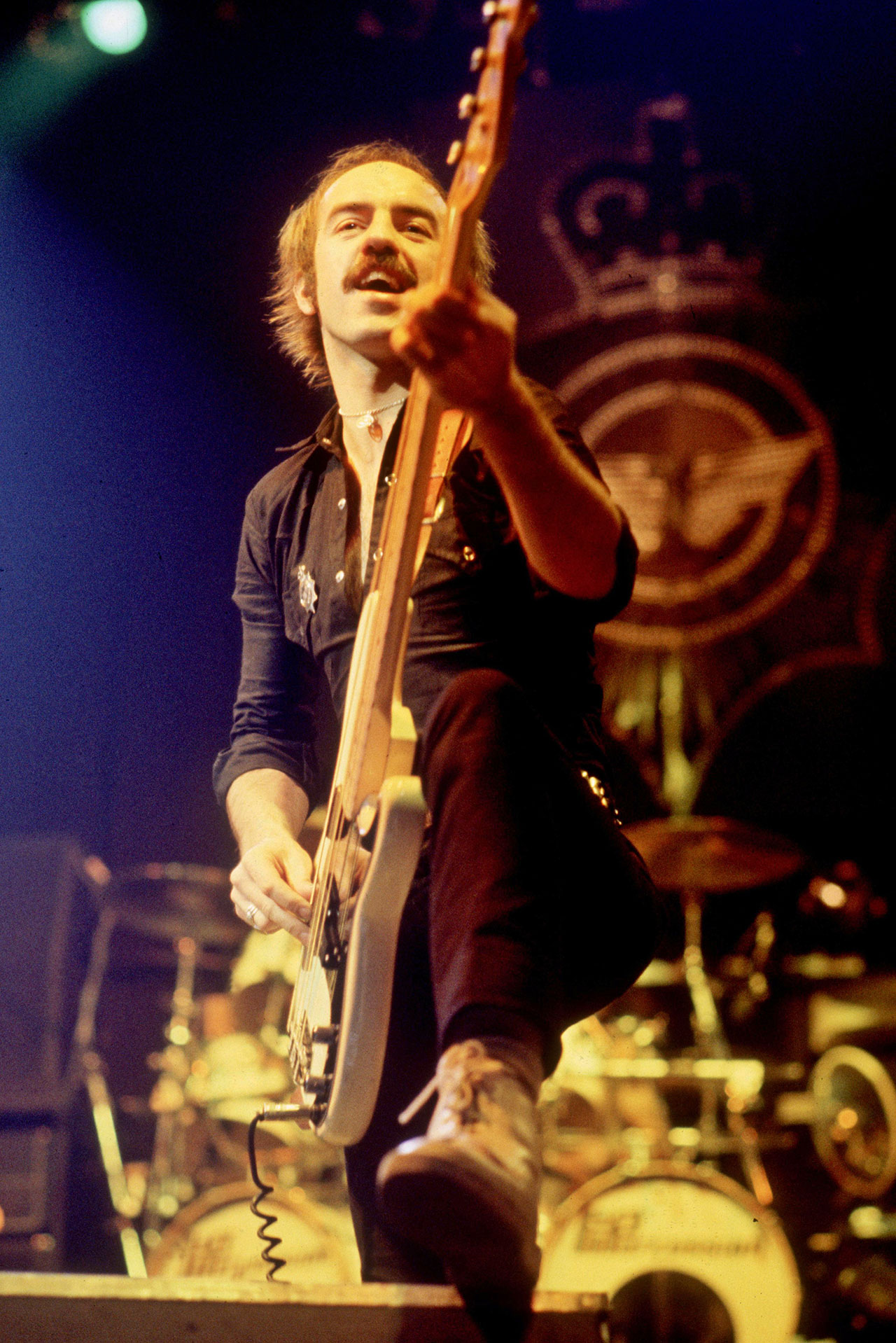

The one band everyone looked up to was Motörhead. Lemmy was a veteran of the psychedelic wars, and one of the few longhairs accepted by the punks. Saxon got the nod to open for them on their Bomber tour in November 1979. These were the biggest venues they’d ever played: Odeons and Apollos, City Halls and Winter Gardens. Twenty-nine dates in total. They don’t tour ’em like that any more.

“We met Motörhead for the first time outside their office and they were absolutely fucking crazy,” says Biff. “You couldn’t pick Lemmy as the standout character back then. All three of them had their own thing going. Phil was the spiv. He’d sell you a car. Then you’ve got ‘Fast’ Eddie, who was all over the place. Lemmy was the rock holding it together.”

The two bands shared a bus. Saxon looked on with a mix of bemusement, amusement and horror as Phil and Eddie conjured fist-fights with each other out of nowhere, while Lemmy read a book in the middle of it. Saxon weren’t a drug band – they weren’t even a big drinking band, despite appearances – but Motörhead did their best to persuade them otherwise.

“We had everything that’s illegal within the first half an hour of being on the bus with them,” says Dawson. “Which made most of us ill. If you haven’t had that stuff before it tends to have an adverse effect.”

“Lemmy would make us have vodka and orange,” says Oliver. “He said it was breakfast, because it had orange in it.”

The tour was the break Saxon needed. Motörhead had done Top Of The Pops, QED they were a Big Deal. Audiences who bought tickets for the main draw got there to see the opening act. Saxon were unofficially adopted by the audiences as Motörhead’s kid brother band. It wouldn’t be long before they were a Big Deal themselves.

You’ll have to search hard to find a better year for heavy metal than 1980. It’s all there on the calendar: Def Leppard’s On Through The Night (March), Black Sabbath’s Heaven And Hell (April), Judas Priest’s British Steel (ditto), Iron Maiden by Iron Maiden (ditto), Ozzy’s Blizzard Of Ozz (September), Motörhead’s Ace Of Spades (November). Throw the net wider and you get Van Halen, Rush, Whitesnake…

Saxon didn’t release a classic album in 1980. They released two. The first, Wheels Of Steel, remains their magnum opus. Unless you count the one that came just four months after it, Strong Arm Of The Law. Or the one that followed a full year later, Denim And Leather. That trio of records didn’t just turn Saxon into a figurehead for rock’s new generation, they also distilled the essence of heavy metal into a draught that bands still drink from today.

Not that Saxon were thinking such things when they were sitting on top of a Welsh mountain writing Wheels Of Steel. They’d rented an old farmhouse, and spent a few weeks regretting it. Nothing in the way of entertainment, no pubs and certainly no clubs. Their nearest neighbours are the inhabitants of a teepee village set up by someone who used to be in Hawkwind.

“It was bloody freezing, there was no heating, you’d open the drawers in the kitchen and they’d be full of mouse shit,” says Oliver. “The worst place in the world. But we were there to get a job done.”

Getting the job done is what Saxon did best. They already had a half an album of songs stockpiled from before the Motörhead tour. It didn’t take long to finish the rest.

“We did it as one,” says Oliver. “There weren’t one person doing everything. I’d bring in a riff, then Paul would say: ‘What about this for a chorus?’ Biff would say let’s write it about this. Everybody was throwing ideas in.”

They came down the mountain a month later like five Moseses in grubby Levi’s, clutching their own stone tablet and proclaiming their own set of commandments: thou shalt ride fast motorbikes (Motorcycle Man); thou shall drive fast cars (Wheels Of Steel, Freeway Mad); thou shall not take shit from anyone (Street Fighting Gang).

Wheels Of Steel roared into the Top 5 in May 1980, with the title track, released as a single a month earlier, having gatecrashed the Top 20.

“We did Top Of The Pops with no audience, just in case,” says Byford. “If it went Top 30 the next week, they’d put it on. Just standing in a lonely studio, nobody there. Watch it on YouTube – we’re petrified, you can see that. It was fucking TV, the first time we’d done it.”

Audience or not, appearing on Top Of The Pops had its up sides. Coming across the show’s resident female dance troupe, Pan’s People, for one. “We met them up on the roof,” says Byford. “There’s a photograph floating around of it. We went out with a couple of them, partying. That’s all I’m saying.”

Saxon’s second great album of 1980 came out three months, three weeks and six days after their first. These days it would take a band that long to find the USB socket for their laptop in the studio.

“We were a little bit pressured into it,” says Byford. “I think it took the record company and management by surprise. They thought we were a bit of a flash in the pan: ‘There’s no way these guys are going to do this again. Let’s get them back in to write another before everybody forgets them.’”

Saxon, being Saxon, weren’t about to let anyone forget them. Continuing their tour of Britain’s farmhouses, this time around they pitched up in one near Diss in Norfolk. There they worked up new songs to add to the ones they had left over from Wheels Of Steel.

The result was Strong Arm Of The Law, an album that Graham Oliver calls “Wheels Of Steel 2.” He’s not wrong, although that’s the highest praise possible – Strong Arm was just as stubborn and truculent and anthemic as its predecessor. Its finest songs – the proto-thrash rampage of Heavy Metal Thunder, the jet-plane love letter 20,000 Ft, the JFK-inspired Dallas 1pm – tapped into the eternal Saxon themes of speed, rebellion and freedom (even Sixth Form Girls, belying its creepy-uncle title, was a celebration of teenage life in northern factory towns). The title track brought all those strands together: the exhilaration of playing a gig, the long motorway journey home, the inevitable run-in with the police, the ultimate triumph of Saxon over the establishment. Like all of their great songs, this was no outlaw fantasy – it was real life.

“That happened,” says Byford. “It was on London Bridge. Or maybe it was Tower Bridge. We were in our big American car, and because we were long-haired fucking yobs the police obviously thought we took drugs. They stripped the car, pulled the bloody seats out. They tried the old: ‘We just found this…’ (holds up imaginary packet of drugs) ‘Well it’s not fucking ours!’ We didn’t have anything. ‘The only speed we use is the car.’ That’s the line in the song.”

Strong Arm Of The Law followed Wheels Of Steel into the upper echelons of the charts. A month earlier, Saxon had appeared at the first Monsters Of Rock festival at Donington Park. Their triumphant early-afternoon set sealed their legend as working-class boys done good.

“That was the first time we walked on stage after the huge album sales of Wheels Of Steel,” says Byford. “I suppose we were the underdogs. Everybody wanted us to win. Especially us.”

Saxon played fast and proud. Listen to recordings of the show – no matter how rough – and you hear a band firing on all engines, oblivious to external distractions. Playing Donington would inspire one of their greatest songs, the immortal And The Bands Played On, which would eventually appear on Denim And Leather.

On the other side of the album’s release, Saxon made their first visit to the US, to support Rush. They weren’t quite innocents abroad – there’s nothing innocent about any band that toured with Motörhead – but there will was still an epic cultural disconnect.

“There were certain people in America who just called us faggots cos we had long hair and wore leather jackets and tight trousers,” says Dawson. “It had a different meaning over there. Especially down south. We’d pull into a truck stop and walk into the toilets. There’d be these guys with Stetsons, and guns in their holsters, they didn’t know what to think. They could couldn’t take it in. ‘What’s with these guys walking around looking like women?’”

Saxon didn’t get shot by rednecks or cowboys. Nor did they make any concessions to Rush’s prog-loving audience.

“We hit the stage like we did at every show: ‘You’re gonna fucking like us,’” says Biff. “The sheer bombasticness of what was coming off the stage, the running about, just generally going crazy, they loved it.”

There was a year and one month between Strong Arm Of The Law and Denim And Leather. A blink of an eye for most bands, an eternity by Saxon’s standards.

They certainly weren’t idle. Between the winter of 1980 and the summer of 1981 they toured constantly. They played across Britain and Europe and flew to Japan, which was as alien and brilliant as they expected. They made more appearances on Top Of The Pops, now in front of an audience. In the battle of band versus treadmill, Saxon were still winning.

Tired of freezing farmhouses, they headed to glamorous Geneva in Switzerland to record Denim And Leather. Which brought its own problems for five frugal Northerners. “I remember it being seven quid for a bowl of cornflakes for breakfast at the hotel,” says Oliver. “I went: ‘’Ow much?!’ A true Yorkshireman’s war cry.”

Breakfast might have nearly bankrupted them, but creatively Saxon were in the black. Denim And Leather polished the rough edges of its two illustrious predecessors without losing their blunt energy. Its opening track was Saxon in excelsis. In another band’s hands a song called Princess Of The Night would have revolved around an alluring femme fatale, or maybe a prostitute. In Saxon’s hands it was a love letter to steam train, a song whose magnificent velocity – ‘Ninety tons of thunder steaming through the night’ – was tinged with a hint of sweet nostalgia. ‘If I ever had my way, I’d bring the princess back one day,’ Byford hollers, crying out for a lost love.

“It was something we were interested in,” says Dawson, not unreasonably. “Being a train spotter is a bit nerdy, but if you like it it doesn’t matter what anybody else thinks. We thought: ‘We’re a rock band, we like steam engines, we’ve got a great riff.’ So we just sat down and wrote it.”

Princess Of The Night slotted neatly into the small but growing micro-genre of Saxon Songs About Boys’ Things – bikes, cars, planes, and now trains.

“We were accused of being gay by the biggest metal magazine in Germany because we appealed to boys more than girls,” says Oliver. “I think it was wishful thinking on their part. They wanted to live like we were living.”

Princess Of The Night isn’t the only great 1980s heavy metal anthem on Denim And Leather. There’s also And The Bands Played On, inspired by that Donington appearance a year earlier; Never Surrender, a call-to-arms by a band who can still remember schlepping around the country in a battered van; Fire In The Sky, about a nuclear attack on Sheffield that predated terrifying 80s TV film Threads by three years. Best of all was the immortal title track. Based on a relentless Graham Oliver riff, it was the ultimate celebration of this new strain of heavy metal culture. Where were you in 1979 when the dam began to burst, anyway?

Saxon were so big at that point that their support act in mainland Europe was Ozzy Osbourne. At least that was the plan. Ozzy managed three dates before vanishing minutes before he was due on stage at a gig in Germany.

“It was about quarter past seven, and his band were sound-checking in Germany,” Graham Oliver remembers. “The tour manager came on to the stage and said: ‘Right, lads, get your stuff off stage quick, you can’t play – Ozzy and Sharon are in London.’ That was the first anybody knew about it, fifteen minutes before the doors opened. What happened? I still don’t know.”

They travelled to America, where the bill was flipped and Ozzy headlined (and managed to stay the course this time). Oliver remembers swapping guitars with Randy Rhoads for backstage jams, and meeting Jimi Hendrix’s dad in Seattle.“I lived in a council house in South Yorkshire,” Oliver says. “Never in my wildest dreams did I think I’d be sat in Jimi Henrix’s dad’s house, with his grandmother, who was a hundred and one, talking about Hendrix. It was incredible.”

In early 1982 they embarked on another US tour, which took in four manic shows of their own over two days at the Whiskey A Go Go in Los Angeles. Graham Oliver and Steve Dawson hand-picked the support bands, choosing them from a pile of tapes accumulated in the back of the tour bus. One of the bands they went for was a gang of rising Californian hotshots named Ratt. The other was Metallica. “It was the quality of the demo and the tunes that stood out,” says Oliver. “The others were rubbish.”

Saxon didn’t know Metallica from Adam, and neglected to watch them when they played their set. They were too busy entertaining admirers in their dressing room, Ozzy and Mötley Crüe among them.

“As soon as they came in, they immediately went into these poses,” Dawson says of the Mötley Crüe guys. “It were like they were our best mates even though we’d never met. It was very bizarre. Very LA.”

That surreal introduction didn’t prevent the two bands becoming fast friends. When Mötley Crüe broke through a year later, they invited Saxon to support them. But America proved resistant to the British band, although that wasn’t through lack of effort on their part. They could do nothing but watch as their old mates Iron Maiden raced past them.

“The biggest thing that went against us as far as America goes was that we didn’t have a major label behind us,” says Dawson. “That and the fact that things never seemed to go our way. We did have a big following – we could headline shows on the West Coast and in Texas, but it didn’t really translate across the country. But I’m not complaining. We did alright out of it.”

The last end-to-end classic Saxon record of the 1980s wasn’t a studio album but 1982’s The Eagle Has Landed. Like every great live album, it served as a greatest hits and a record of their imperial phase. Their career never fell off a cliff – it still hasn’t all these years later – but an almost imperceptible commercial decline had set in. Subsequent studio albums swung between the near-classic – 1983’s Power And The Glory, 1986’s Rock The Nation – and the ropey, most notably 1988’s ill-advisedly slick, trend-chasing Destiny.

No one can pinpoint where things started to go awry. Perhaps it was the acrimonious departure of Pete Gill just after they finished recording Denim And Leather. “He was a wild man of the drums,” Graham Oliver says ruefully. “It was a blow for me and a blow for the fans.”

Steve Dawson was forced out in 1986, taking some of Saxon’s original spirit with him. Oliver followed a decade later, leaving Biff Byford and Paul Quinn as the only remaining members of that original Gang Of Five.

Byford isn’t one to look back, but he knows the sound of those three classic albums his band made nearly 40 years ago still resonates today. “Am I proud of them? Of course I am,” he says, eyebrow shooting up impatiently.

Oliver and Dawson – who reunited in the late 90s and currently trade as Oliver/Dawson’s Saxon – naturally agree. “You could say they might have sounded better, you might say we could have done this or that better, but at the time it was the best it possibly could be,” says Dawson. “We had an effect on what were happening at the time,” adds Oliver. “Just ask Metallica or Mötley Crüe.”

Decade Of The Eagle is out now via BMG Records. Saxon’s new album Thunderbolt is released in February.

Saxon - Decade Of The Eagle album review