Be-Bop Deluxe were an anomaly right from the start. Along with Sparks and the Sensational Alex Harvey Band, they were one of those rare groups that defied

easy categorisation. You would need to draw a Venn diagram of prog, glam and new wave to find a place for Be-Bop Deluxe to comfortably sit in.

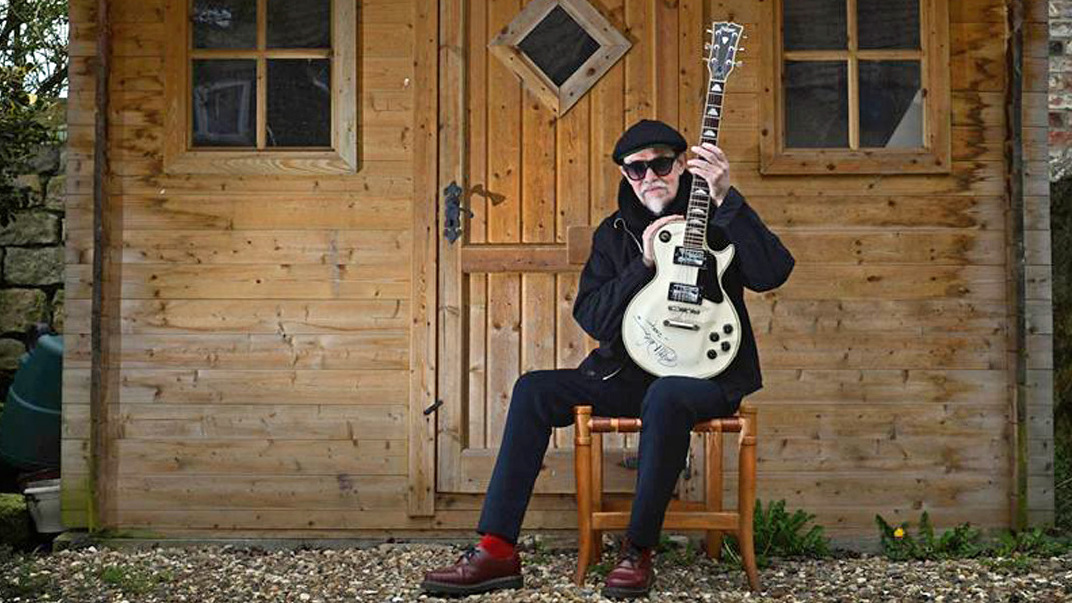

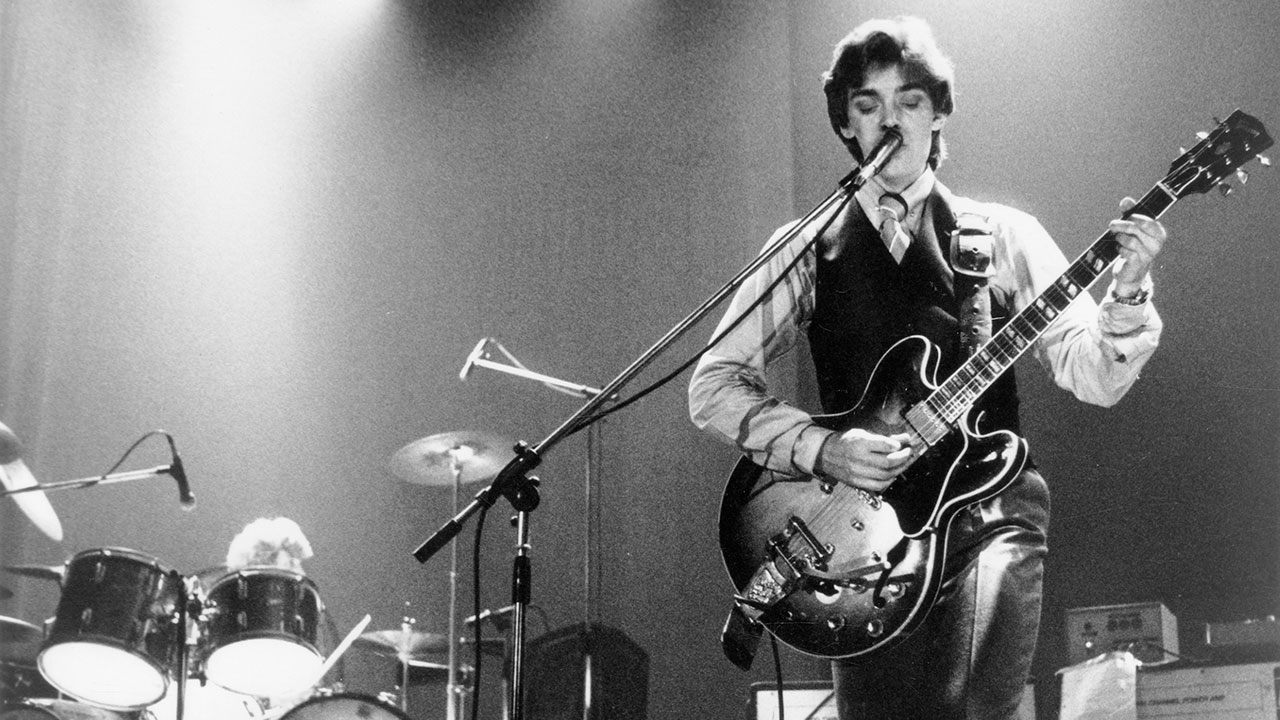

Over the course of five ever-evolving studio albums and one live document, Be-Bop Deluxe didn’t so much make sense of their present as anticipate the future. In leader Bill Nelson, they possessed a frontman who stretched the possibilities of the guitar both on stage and in the studio. His restless nature and desire to continue moving forward led him to dissolve the band and work within the fluid format of Red Noise before setting up his own label and lending his production skills to a variety of post-punk luminaries.

Nelson’s ferocious work ethic has seen a vast output of self-released material that must make less productive acts blush. With 1977 album Live! In The Air Age re-released and upgraded to a 16-disc box set, the softly spoken Bill Nelson casts a rare look over his shoulder to discuss a very idiosyncratic career.

Was music a feature at home?

Yes, it was. My father was a semi-professional saxophonist. He had a big band in the late 40s and early 50s and so I heard a lot of swing music. Benny Goodman and Glenn Miller were played a lot around the house. When I was eight years old he actually tried to teach me to play the saxophone, but I didn’t take to it. I had a bit of a difficulty reading music, so he kind of gave up on me; he didn’t think I’d make a musician. But then, when I was about nine or 10, my brother had been bought

a little toy guitar for Christmas and I figured out how to play The Third Man theme. I decided then that perhaps there was hope for me after all!

When I was at school I met a fellow pupil who was also at the same stage as myself and the two of us would get together at each other’s parents’ houses on alternate nights and try to figure things out. Basically, putting records on that we liked – the Ventures or the Shadows and Duane Eddy, who was a huge influence – and then picking the notes out. We sort of propped each other up for a while and actually, he eventually became the rhythm guitarist in the first line-up of Be-Bop Deluxe.

You’re part of that generation of British musicians that went through art school. Did that feed into your music?

It was in the early to mid-60s and there was a lot happening in terms of popular culture. There was the appearance of pop art on the scene and at the same time there was the mod era and in some ways, the two seemed to intersect. At the same time, having access to the art school library, I was able to pick up books on the Fluxus movement and read about Yoko Ono and John Cage and that side of avant-garde things was introduced.

I did a score for a college play – Ibsen’s Peer Gynt – and played it live. I used a tape which had cut up bits of tape and was reversed and stuff, and I put some nails and bits of metal through the strings of the guitar and prepared it like John Cage because I’d read about how he prepared the piano. I’ve still got the programme and it says, ‘Electronic sounds by William Nelson’ but it wasn’t really electronic; it was manipulating stuff. It was a very exciting time. All those things that we were picking up and reading about art tended to bleed over into the way you thought about music.

Your debut solo album, Northern Dream, is almost like a home recording. Is this where your interest in production began?

It was. It was recorded in a studio called Holyground. It wasn’t really a recording studio; it was a guy called Mike Levon who was a recording hobbyist, and he had a spare bedroom, which he’d put some soundproofing in. He had a two-track stereo tape recorder and a little homemade mixing desk. He’d started a little label called Holyground, which had put out some local folk music.

I got involved playing on albums by various people and as a result of that, he said, “Why don’t you do something of your own?” so I wrote a bunch of songs and recorded Northern Dream. That then got into the hands of John Peel and he loved it. He played it on the radio in its entirety. It was unbelievable! I didn’t have any real ambitions to become a full-time musician; I didn’t think that was possible. I was just a kid from Wakefield and I thought it only happened to people from London.

EMI wanted to sign you as a solo artist but you held out for Be-Bop Deluxe. What did the band format give you?

I don’t know, really. It was partly because I’d put the band together with some friends so I felt kind of loyal. I wasn’t calculating what the best thing was to do in terms of a career because at that point I didn’t really have a career.

When Peel played Northern Dream, EMI happened to hear it and got in touch and asked me to go down and see them. At that point, I’d just formed the first line-up of Be-Bop Deluxe and we’d only been together for two weeks. I went down to London and they said, “We’d like to sign you as a solo artist and put you with some session musicians to re-record Northern Dream” and I said, “No, that’s finished and I’m not doing that now because I’ve got a band.” And they said, “Can we hear it?” I played them some songs that I’d got down on tape and they said, “Hmm. We’ll have to come and see you play live.”

We had a gig in a pub in Leeds and they came up and said, “No, we don’t think this is going to fly but we’ll still sign you a solo artist” and I said, “No, it’s the band or nothing.” So they said, “Okay, we’ll give you a bit more time to get things together and we’ll come back and see you again.” They came back six months later and it was still the same story. I kept on saying “no” and then we got a gig supporting a band called String Driven Thing at the Marquee in London. EMI came down to see how we got on with a London audience and we went down really, really well. So they came backstage and said, “We’ll sign you.”

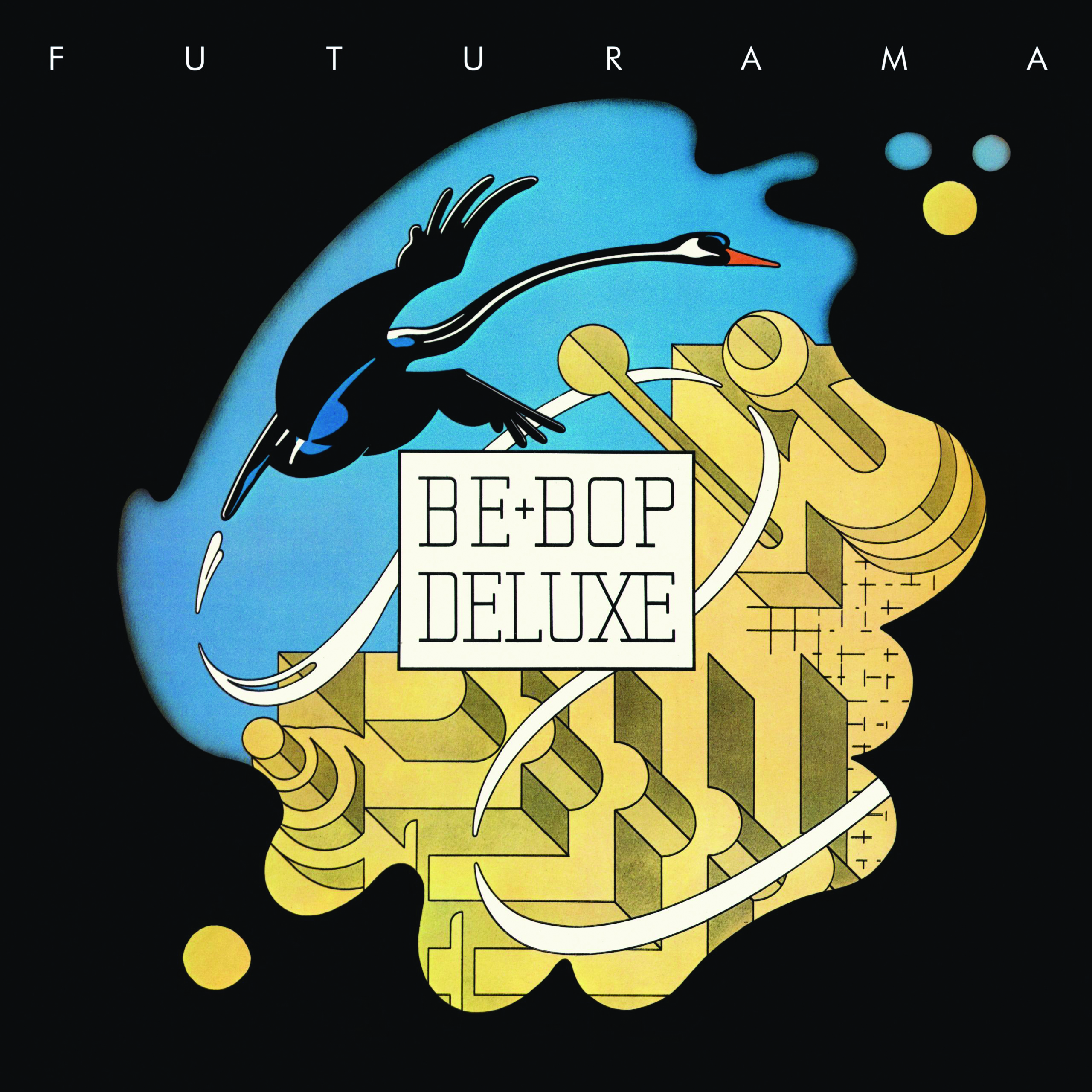

Yet for all that, why did you go through several line-up changes between Axe Victim and Futurama?

EMI were never convinced by the other guys. They kept saying, “You’ve got to get some better people in the band” but I kept it going. We went out on tour with Cockney Rebel and I started comparing my guys with theirs and I thought, “Hang on, this could be better.” At the end of that tour I decided to split the band and try to reform it. Two of Cockney Rebel were about to leave, so Milton Reame-James, who was Cockney Rebel’s keyboard player, and Paul Jeffreys, who was the bass player, decided to join me. Milton knew Simon Fox from Birmingham and so brought him in to play drums.

We did a few gigs and I didn’t feel that it worked. It wasn’t anything to do with personalities – they were nice guys – but it didn’t quite gel musically. I decided to keep Simon and we then set out looking for a bass player and we eventually came across Charlie Tumahai. He joined and went to do the Futurama album. I played keyboards and guitar on that album but we then started auditioning for a keyboards player and came across Andy Clark. We said to him, “You can join us but you’ve got to get your hair cut and get rid of that smelly Afghan coat!”

Be-Bop Deluxe didn’t look like the long-haired bands of the time. How important was fashion and the visual presentation of the band to you?

I didn’t want us to look like everybody else. I’d always had a thing about clothes and fashion anyway. When I formed the band, we’d decided to have a glam image. Playing gigs in Yorkshire with that image at the time was kind of outrageous. It was fine for Bowie in London but not for playing rough pubs in Yorkshire with makeup on! It could get confrontational because when we finished playing we didn’t take the gear off. We’d get in the van and then stop at a chip shop with our full makeup and glad rags on and everybody would be freaking out! I enjoyed that confrontational stuff.

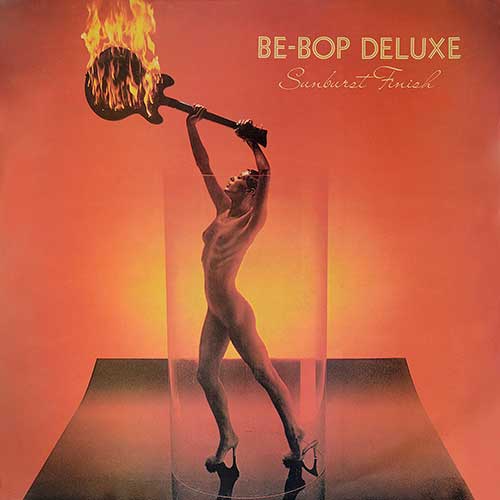

You wanted to produce Sunburst Finish and were paired up with John Leckie for what turned out to be a fruitful relationship. Why did it work?

We got on as people. It was John’s first role as a producer as well as mine. I had ideas about how to do arrangements and layer things and John had been an engineer at Abbey Road for years, so he had all those skills. He picked up ideas from me and I picked up how to work the board from John. The two of us would sit side-by-side and every mix that we did was like a performance with all hands on the faders: “You take care of the drums and I’ll do this.” It was a really good way to learn things. It was a very natural process and we had fairly similar and broad tastes in music and we turned each other on to things that we found.

You wrote Ships In The Night to be a hit – which it was – but you’ve called it an ‘albatross’. Has your attitude to it mellowed over the years?

The record company were saying that we should think about a single for Sunburst Finish. I was always dismissive of that, as I didn’t see us as a singles band. I had an electric piano at home and I came up with that keyboard riff and wrote that song almost dismissively.

It is a bit of an albatross because every time Be-Bop Deluxe gets played in the radio these days, it’s bound to be that one. It’s my least favourite track of all time. But I can’t be too cruel about it because it did do some favours for the band.

The titles of the first three albums allude to guitars. Was this an in-joke?

Well, yes. I think of those first three albums as a trilogy with the guitar as the central theme. I saw a picture of a man reading a newspaper with the headline ‘Axe Victim’ and I thought that could be something to do with guitars, so that became the title of the first album. Unfortunately, the record label took the title a little too literally and I wasn’t too happy about the cover because it made it look like a heavy metal album.

With Futurama, I’d always had an interest in science fiction and I’d always had an interest in world fairs and the one in New York had a thing called the Futurama Ride. There was also a cheap Italian guitar called a Futurama and so all three lent themselves to a triple meaning. And for Sunburst Finish, that was my Gibson ES-345, which my father bought for me in 1964. I still have it today.

How did touring the US go on to inform Modern Music?

The Modern Music Suite, which takes up the second side, is about my experiences of touring America. It seemed very glamorous at first, but for that one hour that you spent on stage, you spent umpteen hours stuck on airplanes or in cars, hotels and endless radio stations. For all my childhood love of America thinking what a magic place it must be, the reality was somewhat different. I realised it was far more alien than I expected it to be. The culture itself was different and it could get on your nerves after a while and so I turned that into the theme of The Modern Music Suite.

Live! In The Air Age was your biggest hit album in 1977. How surprised were you by this?

It sounds weird but I didn’t pay a lot of attention to how things were doing in terms of sale or chart placings; I was just getting on with the music. I suppose it felt a bit odd looking back on it.

As for the live recording, we took the Rolling Stones’ mobile studio out on the road with us. John Leckie and myself sorted through all those tapes later and got what we thought were the best performances, which were used on the original live album.

The opening track on Drastic Plastic, Electrical Language, sees humans communicating through machines. In that context, how do you view the 21st century?

It’s not what it should be. Even writing stuff like Life In The Air Age, that was about a guy who went into a state of suspended animation like Buck Rogers, and he woke up in the future and it wasn’t like it was cracked up to be, so he had a yearning to go back to the past. Obviously, there’s a whole number of great technological advances but in terms of human culture I think we’re on a backward path.

Was the band format a constraint by Drastic Plastic? Did you know that would be Be-Bop Deluxe’s last hurrah?

The last Be-Bop Deluxe album that I wanted to be was actually Modern Music but I was persuaded to hold it together for one more album and so Drastic Plastic is like a halfway step between Be-Bop Deluxe and Red Noise. I felt that we were on a treadmill. Whenever you did anything new and you went out on tour with it, the audience always wanted the previous album, and then when you went out again, they wanted the last album. That was frustrating because I wanted to keep moving forward.

The idea behind Red Noise was that it wouldn’t be a fixed band; it could have

a number of people or no people, apart from myself. I felt that if I continued with Be-Bop Deluxe then I wouldn’t be opening more doors.

Was it a struggle to launch Red Noise?

It was particularly a hard sell for Capital Records in America, who released our records there. I’d recorded the Red Noise album, Sound-On-Sound, and the label sent the tapes to the States and Capital Records couldn’t understand it all. They sent the album out to radio stations to get some kind of feedback and the response was both sad and funny. You’d have people saying, “This is too wacko for us!” and “What is this shit?” So we lost our deal in America. Shortly after that, Thorn Electrical Industries took over EMI and it became this money-driven thing. These financial people started running things and they dumped acts, including Wire and Red Noise. So I found myself without a record deal.

They already had the second Red Noise album, Quit Dreaming And Get On The Beam, but wouldn’t release it. It sat on their shelves for a year-and-a-half. David Bates, an A&R at Phonogram, said, “Why haven’t you got anything out?” and I told him that EMI wouldn’t put the album out, so he said, “I want to hear it” and they bought it from EMI, released it and it went into the [UK] Top 10.

You produced Skids and A Flock Of Seagulls, among others. What kind of freedom did being on that side of the desk afford you?

It was fun at first but after a while I didn’t like sitting behind the desk watching the musicians having all the fun. Eventually, I’d say, “Can I play a bit?” I enjoyed creating a kind of a soundscape and I still do that with my own stuff but I wouldn’t fancy being a full-time producer.

You worked with Gary Numan on Warriors. How strained was that relationship?

It was tricky. It was always a struggle to introduce new things to him, and I ended up mixing the album with the engineer and I then went home. A couple of days later, the engineer called me and said, “I’ve just quit because Gary’s remixing the album and everything we’ve done has gone out of the window.” So I then decided to take my name off of it. I have seen [interviews] in recent years where he’s said he’s regretted doing that and I don’t bear him any hard feelings whatsoever.

You’ve released a bewildering number of solo releases. Do you ever take stock

of what you’ve done or do you keep moving forward without looking back?

I rarely listen to any of my music once it’s released. I kick it out of the door and let it fend for itself. The next project is always more interesting than the last one.

What’s your quality control measure now?

I don’t think of it as quality control because that almost sounds as if you’re on a factory production line watching items of machinery going past and making sure all the screws are tight, and music’s not like that, is it? It’s intuitive and you do what’s required and then you move on to the next thing.