Former Rolling Stone Bill Wyman was born in 1936, a turbulent year of three kings, that saw Adolf Hitler’s alleged master race significantly whupped by Jesse Owens at the Berlin Olympics. Not being a man widely renowned for his sportsmanship, Germany’s sulking Führer duly unleashed a World War that saw four-year-old Wyman (still known by his birth name of William George Perks or, less formally, Billy), evacuated from a modest, blitz-lashed three-up/ three-down family home in Penge, South-east London to the relatively leafy enclave of Mansfield Woodhouse, 15 miles north of Nottingham.

Relocating to the countryside had a profound effect on young Bill. But after playing truant from school to experience more of it, he was packed off, back to London, from a pregnant mother (reluctantly inattentive thanks to Bill’s two younger siblings), to a truly inspirational grandmother, Florence Jeffery, who profoundly influenced the man that he became.

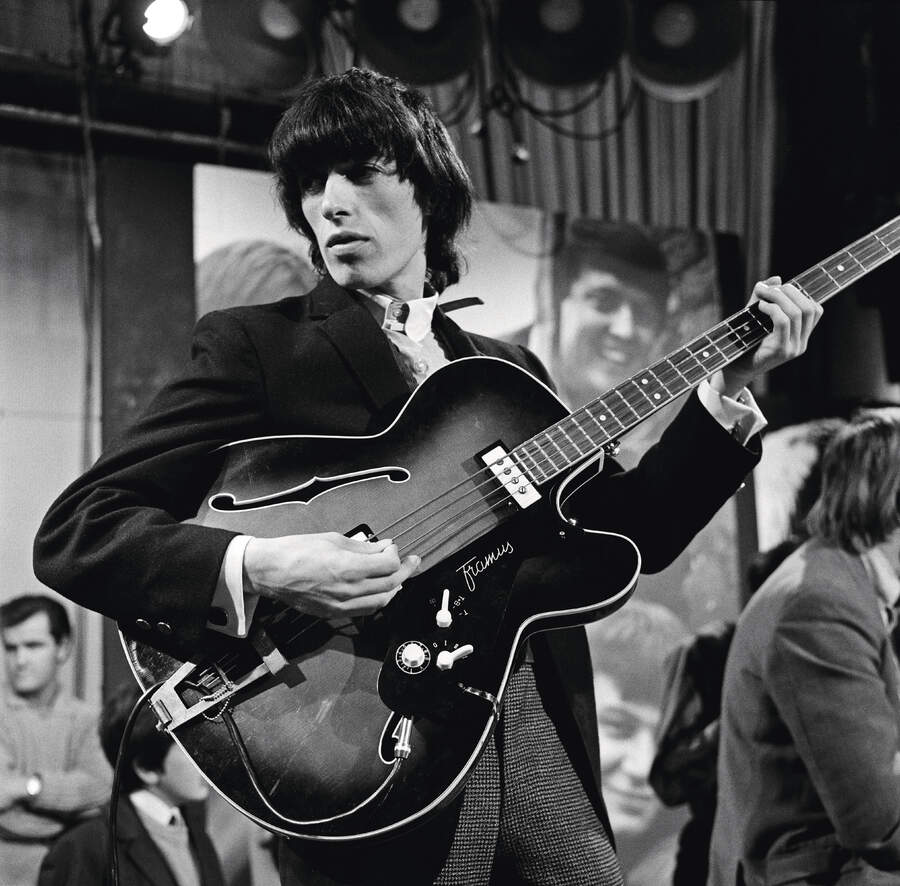

Coerced into leaving school early by an unimaginative authoritarian father, who’d found him a job as a bookmaker’s clerk, Bill was then called up for National Service with the Royal Air Force, and while serving in Germany he discovered skiffle and, via a finger-shredding, tea-chest-and-broom-handle baptism of fire, the bass.

Upon returning to civilian life, Bill married in ’59, formed the Cliftons in ’61, and while just warming to fatherhood joined Brian Jones’s blues band, the Rolling Stones, in ’62. The Stones, as they came to be known, created quite the stir with their long hair, iconoclastic demeanour, penchant for urinating on garage forecourts and finger-snapping brand of no-holds-barred rhythm and blues. In fact they conquered the known world. You might have even heard of them.

Wyman spent 31 years with the band, which involved 19 studio albums, 42 UK hit singles and EPs (including 11 Number Ones), another (rather more high-profile and controversial) marriage, two divorces and a best-selling, feather-ruffling autobiography. For 31 years he stood, stock-still and stone-faced, at the back of Keith, bemused, observing, biding his time.

Excepted from the band’s Jagger/Richards songwriting monopoly, he frequented the clubs with Brian Jones during the band’s heyday, and while neither excessive drinker nor user of hard drugs, found solace in the role of incorrigible swordsman. A role that, while very much expected of the libertine gentleman rock star as the licentious swinging 60s swung into the permissive uncensored 70s, doesn’t translate terribly well into the 21st century.

Upon officially leaving the band in 1993, autodidact Wyman remarried again, formed the Rhythm Kings (a gig-centred combo with a revolving-door line-up of A-list musicians) and set about fulfilling all the ambitions that he’d put on hold while dutifully supplying an ever-reliable bottom end for The Greatest Rock ’N’ Roll Band In The World(™).

He’s since written 14 books, including the million-selling Rolling With The Stones (there are at least two more on the way), enjoyed three decades as a West End restaurateur, been a fearsome charity cricketer (on one memorable occasion taking a hat-trick at the Oval, on another catching out former England Captain Brian Close with one hand “while smoking a fag with the other”), a prolific metal detector-toting treasure hunter and historian, a much-exhibited photographer, not to mention a tireless songwriter and performer.

His long-awaited seventh solo album, Drive My Car was released in August, and there is, as he casually confides over an afternoon glass of chilled rosé in his local pub just off Chelsea’s Kings Road, another one on the way. Just turned 88, Bill Wyman could have spent the last 31 years circumnavigating the globe, holed up in a never-ending series of five-star gilded cages to perform, somewhat ironically, (I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction every single night of his professional life to packed stadia, as he dutifully studied Keith Richards’ arse for cues. But sometimes, for some, the life of a Rolling Stone simply isn’t enough.

Would you define yours as a happy childhood?

It was, really, because although there was tremendous danger all day, every day, sleeping in air-raid shelters most nights, going to school with gas masks, everybody had the same problem. It was just normal when you were a kid. Parents understood it more, so were more scared than you were, but there was such a wonderful community spirit that doesn’t exist any more. Everybody helped everybody else with clothes, food, love, attention.

That was the great thing about it, the closeness of the family units and the way everybody shared. It was amazing and really helped, because some mornings my mum and dad wouldn’t get us out of bed because there wasn’t any food. Then they’d scrounge some off the neighbours, a bit of bread with something horrible… We had jam sometimes. But it was a constant struggle. It was a nice childhood, though, because you had friends all around. You had nice times, in between the horrors.

Your grandmother was an important presence during your formative years. What was the most important and enduring life lesson she taught you?

Everything: collecting; making scrapbooks; writing a diary – she started me doing that when I was five; learning about literature – she’d read me poems and classics like Treasure Island and Robinson Crusoe. She was extraordinary. Taught me my maths, everything. And she gave me love and attention, which my mother wasn’t able to do - she had two other children and she was pregnant in Nottingham [during his mother’s pregnancy, five-year-old Bill returned to London to live with his maternal grandmother], so she couldn’t… And my dad was in the military, so we didn’t get cuddles or told we were loved by our parents.

But my grandma hugged me, told me she loved me and read me bedtime stories, so she was a godsend. She gave me piano lessons, took me to the Royal College Of Music where I passed my first two piano exams. It’s through her I really got into music. She got me into the local church choir which started it all. She did everything. Everything that I do now, it’s all from her.

Your National Service with the Royal Air Force couldn’t have been an entirely negative experience, as you signed up for an extra year.

I only did it because you only had to serve an extra ten months and you got twice as much money and leave, and were more accepted by the powers that be: sergeants, corporals, that lot. They’d boss you around if you were a novice kid doing National Service, but if you were thought of as a Regular you were allowed to dress more casually, let your hair grow longer, set your cap into a different shape, all those little things, and you were respected more. So doing the extra time was okay.

And it was at this point, while serving your third year of National Service, in Germany, that you formed your first skiffle band.

Friends in the next room brought Lonnie Donegan music back from London after they’d been on leave - the stuff he’d done when he was with Chris Barber - so we decided to form a skiffle band. I got an old empty tea chest, a broom handle, some sisal string and made a tea-chest bass. The sisal’s so rough, it cut my hands and made them bleed, so I bought a guitar.

I formed the band with a guy called Casey Jones, who was from Liverpool and went on to front Casey Jones And The Engineers. Years later Eric Clapton told me he’d played with him for a short time as well. Anyway, it was very brief, because it was only for the last few months I was in camp before leaving to return to civilian life.

Why the bass? You categorise your role as “not to get in the way, not to be noticed”’. Does the fact that you chose this role say a lot about you as a person?

Maybe, because I was always shy, a bit of an introvert. When I was in the Stones I kept out of the way, basically. I didn’t want to be out front, leaping about like the rest of them, it wasn’t the way I am. I’m too shy to do that, too self-conscious. So I’d stay at the side in the shadows, watch what was going on between the band and the audience, watch the show while I was playing, basically.

And why the bass? Purely because when I was forming my band in South London, three years prior to joining the Stones, there were three guitarists, and I said: “Somebody’s got to play bass.” The lead guitarist said: “I’m not.” The rhythm guitar said: “I’m not.” So I said: “I suppose I’m gonna have to do it.” I didn’t have a bass guitar, so I had to make one. And, unknown to me at the time, I built the first fretless bass. Invented it, so I’m told, about five years before they came out.

Did your relationship with a dictatorial father and your service in the Royal Air Force lead you to appreciate the freedoms and permissiveness of the sixties more than the rest of the Stones?

Well, I was more grown-up, I was older, I’d been around, and they looked at me as a kind of… uncle [laughs]. Not really, but an older person who’d learned a bit more than they had, that was always respected. So when we were on our first flight, London to Glasgow or wherever, they’d be terrified, and I had to cool them all out. Just say: “It’s okay, no problem. We’re all doing it together.” And they were all alright after that. But there were moments where I had to suggest other ways of looking at things they hadn’t experienced before. I was also the guy who told all the jokes.

When you were in the Stones you collected memorabilia right from the beginning – film clips, photos, everything. It’s almost like you needed hard evidence to prove that it was actually happening, that it all seemed too good to be true.

It probably was that, because it started off with me collecting a few things thinking we were going to be around for maybe a year or two, maybe on television once, have two or three records, and I wanted to leave a few things for my son, who was eight months old when I joined the Stones, so he knew his dad was in a band once, and played a couple of shows [laughs].

Speaking of your relationship with your son, your father instilled very low expectations in you. Didn’t he force you to leave school early?

Before my ‘O’ Levels, yeah.

When you became a father were you determined to be different?

Oh yeah, I was totally different. But he was one of ten and his childhood was Dickensian. They all lived on half a pigeon’s egg each in the morning. And his dad was a tyrant who’d hit them with his belt. So while my dad was tough, he was nowhere near as tough as his dad was. I think he thought he was being pretty nice. Although we didn’t.

We three boys slept in one bed, and if we were joking or laughing my dad would yell up the stairs: “Get to bed or I’ll be up there.” Then we’d hear him coming up the stairs, and hide under the bed, so he used to get the broom and hook us out… I wouldn’t say he was a tyrant, but he was very, very firm. His hands were like rocks because he was a bricklayer, so when he hit you you really felt it. It was like being hit with a plank.

At the height of Stones mania were there moments you feared for your life?

On a couple of occasions. Once just outside Los Angeles, we left the stadium having played to five thousand kids, the limo driver chose the wrong exit and we couldn’t get out. Pretty soon the car was covered in kids, they climbed on the boot, the roof, they were banging on the windows and we had to lay down on the floor with our feet holding the roof up. We couldn’t get any air because we were just engulfed. That was quite terrifying.

Then the cops came, started swinging their sticks and cleared a way to the helicopter. Keith had a scarf he used to wear and on one occasion some of the girls got hold of one end of it and some the other, then they started to pull and wouldn’t let go. Nearly strangled him. So you had those moments: all your clothes ripped and big chunks of hair pulled out. But it wasn’t frightening, terrifying or really dangerous, you just had to laugh it off in the end.

During the sixties, when people weren’t screaming at you, could the life of a touring Rolling Stone get monotonous, because you all sought escape routes: drink, drugs, sex. From the outside it looked like you could have anything you wanted, except actual satisfaction.

It was pretty dismal, because you never really saw anywhere. You flew into a town, you’d be straight into limousines at the airport and then straight into the underground car park of the hotel. You then had to wait while they cleared all the girls out of the corridors - and the rooms sometimes - before you could go up to your room, and then you were stuck in your room until you went to do the show. You did your show, went straight back to your hotel room, where you stayed until you got up in the morning and left for the airport to go to the next town.

There were always girls everywhere, in the elevators, on all the floors, trying to find which rooms you were in. Sometimes they climbed the bloody drainpipes and fire escapes to get to your rooms. But it was all kind of fun, particularly for Brian [Jones]. He thought it was hilarious. You can see him laughing in all the pictures.

The Rolling Stones were originally Brian’s band, yet his role was gradually eroded until he seemed to lose control of his entire life.

[Stones manager ’63-’67] Andrew Oldham decided to get Mick and Keith to start writing songs because he realised that Mick, being the frontman, would probably be the most famous later. Brian originally got much more fan mail than the rest of us. All the girls went for Brian. But he was pushed aside.

Then Andrew stopped me, Brian and Charlie doing interviews, which also elevated Mick and Keith’s profile. Obviously it was ultimately beneficial for Mick and Keith to take on the music, but Brian, who I shared a room with at the time, was always a bit sad, upset that we weren’t doing the kind of music he really liked, because we started out doing real blues and he was a blues purist.

He’d kind of lost the band and he didn’t feel like he was part of it sometimes. Which was very sad. Mick and Keith shared a room, Andrew Oldham and Charlie, and me and Brian. That’s the way we always did it. So it was me and Brian that went out to clubs, played with local musicians, picked up girls and had more fun than the others, who used to just stay in the hotel, basically. Mick and Keith used to be writing, they’d come out occasionally, but me and Brian were always out and about.

Did your comradeship with Brian have an effect on your relationship with Mick and Keith?

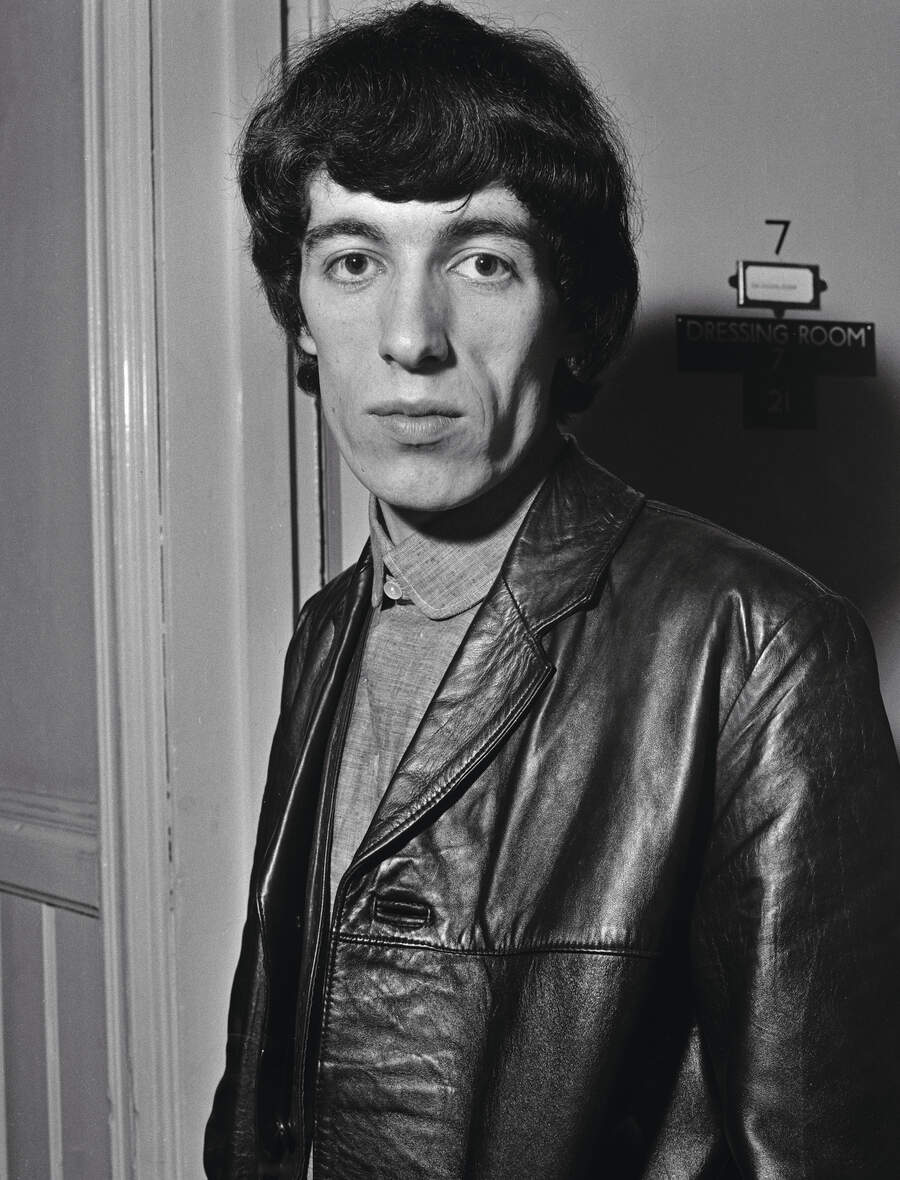

No. I wasn’t just friends with Brian, I was very, very close with Charlie, because we were the rhythm section and got on very well. We were both similar - early married, had a child, went home after London concerts to rejoin our family while the others were out partying at the AdLib with all the other celebrities.

I had a very close affinity with Charlie. I joined the band on the eighth of December, 1962, because Tony Chapman, the drummer from my band in South London who’d been playing with them for a few months, introduced me, then they fired him and got Charlie in from the ninth of January, 1963. But on the road I was with Brian mostly.

There was no malice, they just got fed up with his drug taking. None of the rest of us took drugs. Well, Keith… They did a bit, but there was no heavy stuff for years. I never had any, nor did Charlie, we were always completely clean. We had responsibilities, so we behaved ourselves.

What’s Bill Wyman’s finest performance on a Rolling Stones recording?

I’m proud of a lot, because I did things on the bass that a bass player wouldn’t normally do. Instead of playing a straightforward twelve-bar, I’d lean away, find other notes, do little runs on the top strings and slide. Bass players never did slides until I started. I mean, they did on double basses, but I did it right from the beginning because I had a fretless bass, so it was very smooth. I always got flat-wound strings and had guitars where I could do those slides, on stuff like I’m A King Bee.

I was helped by a great friend who was the bass player with Booker T & The MGs. [Donald] Duck Dunn. I learned so much from him: to play simply, right there with the drums in the groove. Timing perfect, but really simple, leave space, leave air, because it’s very important to do that. Not fill it all up, that’s what lots of people do. You have bass players that sound like lead guitarists.

You mention in passing in Oliver Murray’s 2019 documentary The Quiet One that Altamont nearly led to the death of the Stones.

It was so dangerous that day. I don’t even like talking about it, to tell the truth. It was like a really bad nightmare that didn’t want to go away. Me and Mick Taylor were right in front of where the guy got stabbed, the others were over the other side, but we were on the side of the stage where it happened, so that was pretty horrible.

He just ran and the guys chasing him stabbed him three times with this big knife. Then when we had to leave there was only one helicopter left, and the helicopter pilot came on stage while we were playing and said: “If you don’t finish now, I’m going, I’ve had enough.”

And we were the last ones. So we had to stop, finish the song, rush off stage, and then with the security, and some of the staff and crew, we all climbed into this helicopter which held eight people, twenty of us, all climbing on top of each other, and try to take off. When it lifted, it went sideways until he could finally get some height.

Was leaving England to become tax exiles a wake-up call? Because you must have been living an increasingly rarified existence, in your own country mansions, with a licence to do just about anything, and then, bang, you’re living ‘on the lam’, as Keith put it, in France.

Well, we were living, as you say, in big country mansions, but we had no fucking money. [Stones Manager ’68-’70, Allen] Klein had all the money, and when you wanted anything you begged him to send you some money. You’re in the red with your bank, so you weren’t partying all the time, you were worrying about how to pay your bills.

It was a nightmare. And then [Prime Minister Harold] Wilson comes in, and puts tax up to ninety-three per cent, it was absurd. So we left. We had to leave because we owed the Inland Revenue so much money that, with ninety-three per cent tax, we could never make enough to pay it back. So we had to leave, and then we were accused of being multimillionaires, leaving because we didn’t want to pay our way, but we weren’t.

When Brian died he was over thirty thousand pounds in debt. When I bought that manor in Suffolk I had a thousand pounds in the bank, had to scrape together a mortgage and hope I could continue to make enough money to keep it. That’s how bad it was. Mick and Keith were wealthier because they had songwriting and publishing royalties, but me, Brian, Charlie and, eventually, Ronnie only had about a tenth of what they were getting.

Despite your own high profile, you’ve never lost your emotional connection, fondness and fan-ish enthusiasm for the blues.

I was introduced to the blues by Brian, when I first joined the band, just before Charlie arrived, and they were just playing blues. So I learned about it that way. Because it was never played on the radio, you couldn’t buy the records in shops, you had to import them. Even when I was crazy about Chuck Berry in 1958, when I’d just left the military, I had to write to a record shop in Chicago to buy Chuck Berry records. And then Little Richard had Tutti Frutti and Long Tall Sally come out in 1955 in America which didn’t come out in England until fifty-six.

In those days there were huge gaps between what was happening over there and what was happening over here. So I knew nothing about the blues until Brian taught me about Jimmy Reed, Elmore James, Muddy Waters, Little Walter, all the Chicago greats. And then I had the privilege of playing with Muddy, Buddy Guy, Junior Wells, Pinetop Perkins, Howlin’ Wolf, John Lee Hooker…

Despite the Jagger/Richards credit, would you or Charlie often change the whole direction of a song with a deftly applied bass line or rhythm pattern, and was this an intrinsic part of the band’s creative process? After all, the key to changing a reggae song called Never Stop into a rock song called Start Me Up is all in the bass and drums, surely?

And Satisfaction. I’m the only guy that goes to the four chord. Everyone else, including Keith, is still on the root note. And that started off as a bloody country ballad, until we got stuck into it. Then when we were voting on what was gonna be the single from the album, there were seven of us that voted – all the Stones, Andrew Oldham, and Dave Hassinger, the engineer at RCA studios. Five voted for (I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction, and two voted against. And the two against were Mick and Keith.

How did your fellow Stones react to your success in 1981 with the hit single (Si Si) Je Suis Un Rock Star?

Keith thought it was great, Mick thought it was a bit silly, but the others liked it. It’s still the biggest solo hit from an original Stone. But I didn’t write it for me. I’d already done three albums of my own and wanted to start writing songs for other people, so I wrote that for Ian Dury. When I played it to Billy Lawrie and Lawrence Ronson, who ran a publishing company, Billy said: “Fuck Ian Dury, that’s a hit. You’ve gotta do it.” So they talked me into it.

As the eighties progressed, did the feud between Mick and Keith that kept the Stones off the road for seven years give you a taste for a fully independent life outside of the band?

Well, me and Charlie thought it was ending. We thought the band was folding, and so did [Stones’ financial manager 1970-2007] Prince Rupert [Loewenstein]. Everyone involved was worried, because we just didn’t play, and only released repackaged stuff. I thought I better get on with some other stuff, so I started writing Stone Alone.

Then I opened Sticky Fingers, my restaurant. Which was also a fight. I was going to call it Stones, but was told: “You can’t do that unless we own it and give you ten per cent to run it.” The Stones themselves didn’t say that, it was the management. So I changed the name to Sticky Fingers and it was a huge success for 33 years. But we had to finish it when covid started and I got prostate cancer which, after 15 months of treatment, I was thankfully cured of.

Are you glad you left the Stones when you did?

Well, I should’ve done it a lot earlier… In the eighties. I hung on for a three-tour ending across ’89 and ’90 [three legs of the Steel Wheels/Urban Jungle tour], after seven years of nothing, and I’d ended up with a bank overdraft of £200,000, because we weren’t earning anything. Mick and Keith were totally wealthy, so they weren’t bothered, but me, Charlie and Ronnie were scraping by. Ronnie started to do art to feed his family.

Anyway, I only started playing with them again in the hope it’d only be a couple of years, because I had all these other things I wanted to do. I wanted to do archaeology, write books, do photography, I wanted to play charity cricket, I wanted to do all these other things. And thirty years on I’m still wanting to do them, to tell the truth.

So I was so happy to leave in the end. Which they absolutely didn’t like, and refused to accept. They said: “You have not left.” When they were doing the plan for the coming year, I said: “Well there’s no point me discussing it, because I’m leaving.” And they went: “You’re not leaving.” I said: “I am leaving, I’ve left.” And they wouldn’t believe me. Two years went by, and they were putting the band together again to make a new record in ’94. They said: “Are you still in the band?” I said: “I left two years ago.”

Mick and Charlie tried to talk me out of it, bless ’em, but I didn’t want to. I just dropped everything. Cleared the air. Gave up a career, a terrible marriage… Got married again and formed the Rhythm Kings with Georgie Fame and Gary Brooker, just for fun.

When you left the Stones, did you think they’d carry on with the band as long as they have?

When Charlie left, I thought they would close. I really did. They could replace the bass, but I didn’t think they could replace Charlie, and his charisma, and what a great guy he was, but they went on, which surprised me. I wouldn’t say it disappointed me, but it surprised me. I think it would’ve been a good time for them to… But I don’t think they’ve got anything else to do, otherwise they’d do it, wouldn’t they?

I’ve got six different things I’m doing all the time, and I’m so happy doing them, but I don’t think they… Well, Ronnie’s got art, as a second thing… And Mick’s tried to do movies and things but hasn’t really succeeded, and he’s done solo stuff which really didn’t work as well as it should’ve done either. And so they just… It’s just the Stones all the time.

Losing Charlie must have been a hammer blow.

We were always close. After I left the band, until he died, we saw each other every week. He would come to the house. “Can I have a cup of tea, Bill?” And we’d spend an hour or two chatting. So when the Stones had that one track with Charlie on it [Live By The Sword on last year’s Hackney Diamonds], Mick and the producer Andrew Watt called to ask me to play on it, and I was quite happy to do it, actually. Just the one.

I wasn’t crazy about the song, and I wasn’t crazy about the way they’d done it. It was just full of guitars, and there was no air in it. No spaces, no gaps. There are probably eight guitars on there, instead of two. It could have been done so much simpler. But that’s the way they do it, bless ’em. It was hard for me to put a bass in because there wasn’t a lot of room.

Anyway, after I’d finished my part, and was happy with it, I said: “Have you got any other songs that I could do while I’m here?” And they said: “Yeah, there’s another one.” So they set it up, and I played bass on it, and they said: “We’ll save that for the next album.” So I might be on the next album as well. Elton [John] came in after me to put his piano on it, so we had a chat, but you can’t really hear his piano. Just odd little notes here and there, because the track’s so busy. But it was nice doing it because it was me and Charlie again.

That’s the only reason I did it. Because when they asked me to play the O2 in 2012 they didn’t even give me a soundcheck. I said: “I need to soundcheck because I’m playing with [Darryl Jones’s] bass equipment and I don’t know what it sounds like. And I’m playing two tracks. And you only told me which two tracks yesterday.”

They were more interested in getting the sound right for one of the new girls who was on stage [Mary J Blige guested on Gimme Shelter on the first of the two nights that Wyman played], and I just had to wing it, basically. It went over very well in the end, though, so I was very happy.

And everyone in the audience was very pleased to see you.

I know. But they only let me do two songs [It’s Only Rock ’N’ Roll (But I Like It) and Honky Tonk Women]. I thought they’d let me do four or five, actually. Then they wanted me to fly to New York to play there for two shows, and I said: “How many songs do you want me to play?” And they said: “Two.” I said: “No thank you. I’m not flying to New York for five days to play two songs.” So I didn’t go.

What was the catalyst for recording your new album Drive My Car? It’s got its own sound, a nice understated rhythm and blues feel, and it’s your first in nine years.

I originally wanted to call it Rough Cut Diamond, because there’s a song on it that goes: ‘I’m just a rough cut diamond, and everybody says diamonds are a girl’s best friend’. But then I found out the Stones were going to call theirs Hackney Diamonds, so I thought people are going to think I’ve copied it. So I called Mick, and he said: “We can’t change it, you’re on your own, mate.” So I changed it to Drive My Car, which worked perfectly actually.

Anyway, on my previous albums I used horns, piano, backing vocals, percussion, all kinds of stuff, and I thought this time I’d just make it simple – bass, drums, guitar and that’s it. Like JJ Cale, Randy Newman, those kind of people, a simple laid-back feel.

In the context of the album, Dylan’s Thunder In The Mountain, Taj Mahal’s Light Rain and John Prine’s Ain’t Hurtin’ Nobody all sound like they come from the same source.

Well, they’ve all been done in the same style, with the same musicians, so it flows. It doesn’t go up and down like all my other albums. I used to do a fast one, a slow one, a bit of jazz, a bit of blues, a bit of country, it was a complete mixture, and it never had a flow. But this last one just had that feel all the way through.

You apparently bonded with Taj Mahal when he discovered you were a member of the Royal Horticultural Society. Has the garden always offered a place of sanctuary, even during the madness of the sixties and seventies?

Yeah. I went to the Chelsea Flower Show once, but it was a bit like a football crowd. I’ve always loved plants. All my photography is butterflies, nature, flowers, and when I’m in the country, just walking in a field or down a small alleyway through a little woodland, that’s where my religion is. I can’t go to a church and sing hundred-year-old hymns, it doesn’t do it for me. My spirit’s in nature. Always has been.

Do you think that this love of the countryside takes us back to your evacuation?

Nottingham, yeah, going to school through the woodland and the little countryside lanes. Absolutely. Gedding Hall, my manor in Suffolk, is right in the middle of fields and farmland. I’ve had it 56 years now and nothing’s changed. It’s wonderful to go back there. It goes back to 1480, some of its parts are pre-Henry VIII.

You’re very historically minded and a keen metal detectorist. How did that all start?

When I bought the manor, some workmen found a beautiful 16th-century water jug while sorting out the pipes, and I figured there was probably other stuff down there. So I bought a metal detector and started doing archaeology in my garden. I found amazing stuff: silver pennies from Richard I… a leaf arrow head from 5,000 BC. Then I found a Roman site in our village. I asked a farmer if I could go in his field, started detecting and found Roman coins. That’s when I really got into archaeology and wrote Bill Wyman’s Treasure Islands.

What’s the most impressive thing you’ve ever turned up while metal detecting?

A gold half-noble from Richard III’s time – a year’s pay for a man at arms. I’ve found three gold coins now and about sixty silver, but that half-noble was extraordinary. It was just lying in this field. Went down about two inches – gold coin.

As a keen historian have you considered having your DNA tested?

I’ve done it. Every time I used to say : “I’m English”, my girls [since his third marriage, to Suzanne Accosta in ’93, Wyman has fathered three daughters] would say: “No, Dad, you probably had ancestors in Spain or France.” And I’d say: “No, I’m not Latin, I’m English.” And they said: “‘Okay, we’re going to do your DNA.”

So they paid for it, and when we got the results they were shocked. I’m ninety-eight per cent English and two per cent Northern Germany, God knows where that came from. But it shows thirty-two per cent Midlands, twenty-nine per cent southern England, around Kent, and thirty-odd odd per cent East Anglia. And Suffolk’s where I’ve got the manor.

Any regrets about your life?

Regrets? I should have left [the Stones] earlier. I should have left in the eighties when it was falling apart. But of course it was fortunate that I did wait, because we had that wonderful fifteen months in ’89/’90 doing the tour of America, Europe and the first tour of Japan. We played a hundred and twenty shows in fifteen months to seven and a quarter million people. It was a glorious thirty-one years, because I travelled, met and played with wonderful people, had fantastic receptions, made great records. And I wouldn’t change it, but everything else since has been just as good, if not better for me.

Drive My Car is out now via Ripple Productions/BMG.