Inspired into action upon witnessing the Sex Pistols, English-degree student William Broad entered the embryonic 1970s punk scene as guitarist with the band Chelsea, before swapping specs for contacts, bleaching his hair and recasting himself as Billy Idol: smouldering, Smash Hits-friendly frontman with Generation X.

After sneering his way into the nation’s hearts and charts via Top Of The Pops, Idol enjoyed significant success with Generation X, before decamping to New York and reinventing himself as a solo artist for the MTV generation, with the assistance of producer Keith Forsey and guitarist Steve Stevens.

Hitting on a perfect blend of punk attitude, rock sonics and 1980s dance, Idol enjoyed a string of hits – including White Wedding, Rebel Yell, Eyes Without A Face and Flesh For Fantasy – that established him as a major star on both sides of the Atlantic, scoring Top 10 hits in both the UK and USA.

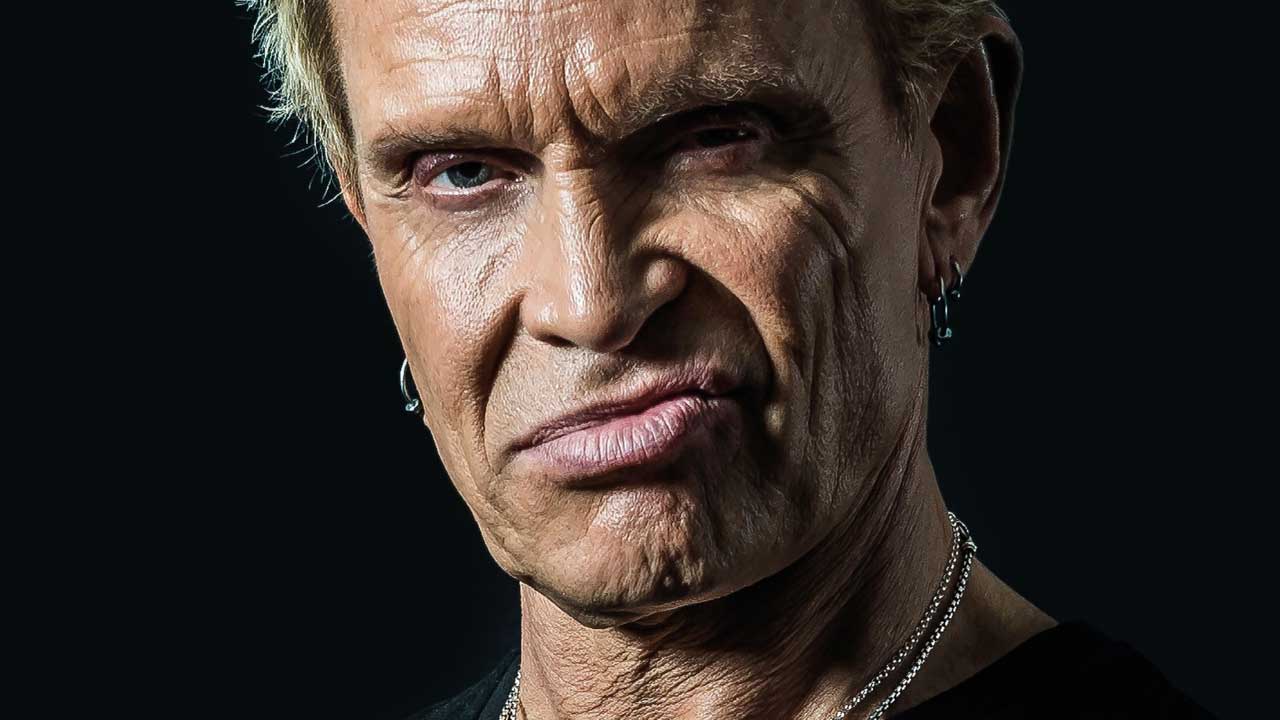

Following a serious motorcycle accident and an extended flirtation with chemicals, Idol is back at the peak of his powers with last year’s The Roadside EP – his first solo studio release since 2014’s Kings & Queens Of The Underground – and begins a UK tour in June.

You were born in Middlesex, but moved with your family to New York when you were two and came back aged six. Did arriving late into school, with an exotic accent, set you apart from the other kids?

I don’t remember being in England before going to America, but I was certainly aware that I was English, because I’d never pledge allegiance to the flag at school. I did come back to England with an American accent. At school it was all: ‘Give the football to the American kid so we can hack him down.’ I had a crew cut, ‘plimsoles’ were ‘sneakers’. But obviously I got my English accent back, and I try to hold on to it now because it just feels good.

Your parents were regular churchgoers. Did you share their faith? Did you enjoy a close family relationship?

My mother was very religious, an Irish-Catholic who thought of herself as Catholic even though she joined the Church of England. The first thing I did in front of an audience was read from The Bible in church. But I rebelled against all of that.

I wasn’t trying hard at school, and eventually, between the ages of fourteen and sixteen, my dad didn’t talk to me for a couple of years. I had really long hair and he couldn’t stand it. That was when I got really interested in the rock scene. A teenager we knew would give me Rave magazine, so I’d read up about all the groups. I had all The Beatles’ singles, and I’d go around to a friend’s house who had all the Rolling Stones’.

What I liked about the music scene was it gave you a sense of freedom; it was just so alive, as opposed to your parents who were still so fuddyduddy. They couldn’t help it. They’d grown up with the depression and the Second World War, and couldn’t imagine the world was going to give them anything.

Whereas we’d grown up watching all these bands leaving where they lived, going around the world, expanding their horizons. My parents were always going on about getting qualifications. But there’s no qualifications in rock’n’roll, it’s based on what you can do and how you go about doing it. We looked askance at our parents’ world, not realising what they’d gone through. We were able to dream a lot more.

Talking of qualifications, why did you drop out of your English degree at Sussex?

We were starting to see the Sex Pistols, knew the whole scene down at Sex – Vivienne Westwood and Malcolm McLaren’s shop down the King’s Road – we could see this thing was going to happen. Even if it was only for the two hundred people who were into it in London, we were going to do it.

We never imagined it was going to explode like it did in England after the Pistols went on the Grundy show. In 1976 I told my parents I was leaving university to join a punk rock group, and they didn’t even know what a punk rock group was, let alone what it meant to join one. Then I met Tony James, knew of Mick Jones, The Clash and all these other people, and I knew it was going to happen. I didn’t know what it was going to lead to, but it was happening and it was fun.

Did you have musical ambitions prior to joining the punk scene?

I started out trying to play the drums when I was about seven years old. Then I realised John Lennon and Paul McCartney were at the front, writing the songs, playing the guitars, so I started teaching myself the guitar at ten, just to have something to sing along to.

Music in the sixties was really exciting: it went from bubblegum to crazy psychedelic stuff like Sgt. Pepper’s, and then back again to rock’n’roll with the White Album, the Stones, Captain Beefheart. Then in the seventies we got into the Velvet Underground. We also started to realise that even if our musical ability isn’t great, there’s music we can play. The Stooges gave us hope. We knew we could never do what Led Zeppelin were doing, but what if you’re not the greatest musician and still wanna do it?

Punk rock opened the door, said if we can’t beat these other people at their own game, we’ll change the playing field. And that’s what we did. If you went to see the Pistols every week you’d see these guys were still learning to play their instruments, but they’re on stage, writing great songs, and having a great time while they’re doing it. And also telling everybody to fuck off, which looked like great fun.

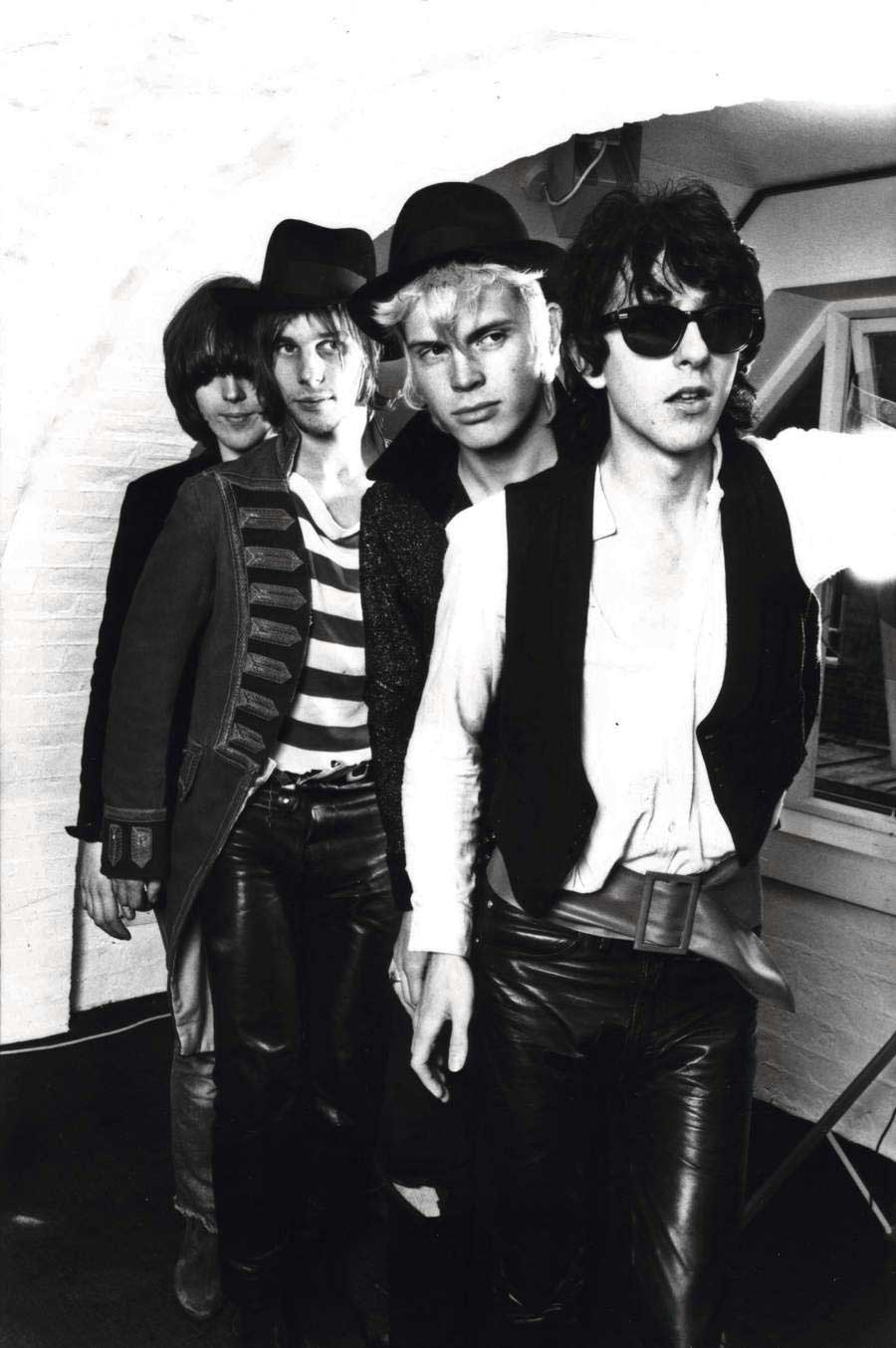

During your time with Chelsea, you rapidly metamorphosed from William Broad, guitarist, into Billy Idol who – with newly blond hair, contact lenses and a new level of self-confidence – simply had to be a frontman.

We didn’t want to be in a retro band, which is what Chelsea [fronted by Gene October] was, me and Tony [bass] wanted to be in a full-on punk group. We did Chelsea for a few months, but were always writing songs for me to sing, songs for our age group: young twenties, late teens.

We made the move inside Chelsea, really, taking [drummer] John Towe, then finding Derwood [Bob Andrews, guitar], and kicking off Generation X in the November of 1976. We finally had the punk rock group we’d dreamed of.

To the casual observer it looked like Generation X enjoyed overnight success, that you went straight from opening The Roxy to being on Top Of The Pops.

Me and Tony got on well. We found Derwood playing in a youth club in Fulham, doing Jimi Hendrix and Deep Purple stuff. We knew we all had to be a little different. That’s what Lou Reed and David Bowie had been saying to us: you’ve got to be yourself, find out who you are and be it. So we knew we’re not going to be the Sex Pistols or The Clash or Buzzcocks, we’re going to be Generation X.

Generation X appearing on Marc Bolan’s TV show Marc in 1977 also seemed to be a pivotal moment in your career.

We didn’t realise what was going to happen. We thought it was going to be a gestation period where we’d latch on to this little scene to get our shit together. And then it exploded. Next minute, every record company in England wanted their own punk rock group, so you were being offered all these things and playing places like the Marquee.

You had to have a record out to play the Marquee in London, but there we were, without a record, selling it out That came as a shock to the powers that be – even the club owners. That was part of the excitement: you could harness the power of the fans. We were thrown into it, television, everything, learning as we went.

And the hits kept coming: King Rocker, Valley Of The Dolls…

I preferred Generation X’s first album. Then Tony wanted to turn us into a more… not a mainstream rock band exactly, but [second album] Valley Of The Dolls seemed to be moving in that direction. I was writing songs with Tony, so I was part of doing that, but in my heart of hearts I wished we’d done another album like the first.

So with the Gen X album Kiss Me Deadly I straightened everything out, stopped the rollercoaster thing we were doing with the drums, put the speed back in with songs like Dancing With Myself. So we did have a bit of a falling out among ourselves over where we were going and what the direction was, which broke us up in the end.

That’s the thing about groups, they’re great when you’re all going in the same direction, but not so great when you’re not.

Did you fear at that point that this might be it, that your time in the public eye might be coming to a somewhat premature end?

Yeah, it was a weird time, but I was already finding people I’d work with to build my solo career later. That last Gen X album was the first Billy Idol solo album, really.

How did you begin working with Kiss’s former manager Bill Aucoin?

We’d had problems with a Generation X manager who was machinating between different band members, and eventually, in seventy-nine, he brought a High-Court action against us. This was another thing that stopped the momentum of the group. We had a big block of time where we couldn’t play, which caused a lot of dissension. We tried playing as Wild Youth for a bit, to keep the band going, but he stopped us.

That’s when I started to take heroin and stuff like that. So that didn’t help me and Tony’s relationship. At the same time, while talking with the record company about potential managers, Tony said, as a joke, what about the guy who manages Kiss? And Chris Wright and Terry Ellis, the heads of Chrysalis Records, knew Bill Aucoin, who came over, met us and agreed to manage us.

Eventually I said to Bill Aucoin that what we need is a producer who’s got one foot in the rock’n’roll world and the other in dance music. I wanted to put punk rock with dance music. It’s crazy, but that’s what I wanted to do.

How did you first meet Steve Stevens?

Bill Aucoin knew Steve in New York. I did look around for other people as well. But as soon as I hooked up with Steve I realised how great he was. I always looked for incredible guitarists, like Derwood in Generation X. Even inside Gen X we didn’t just play two-minute snappy punk songs, we had stuff like Kiss Me Deadly, Promises Promises which is seven minutes long. We wanted to stick out, so we broke all the rules. I intended to carry on making eclectic music.

MTV loved you; the videos for Dancing With Myself and White Wedding were on heavy rotation for months. It must have been a great time to be Billy Idol.

It was really fantastic just being in a new country. After months of walking around New York wondering: “What the fuck am I going to do with Billy Idol? How’s America going to get into it?”, I suddenly realised that Dancing With Myself was in this thing called the New Wave Dance Chart – which I didn’t even know existed. This was when I realised I didn’t have to change a thing.

At first, mainstream radio wouldn’t play my music because I had a punk rock image, which they didn’t believe sold advertising dollars. College radio and then MTV gave us a platform. Then the kids who were watching MTV phoned the radio stations, and they folded and there we were on the radio.

Bill Aucoin, who’d been in television in the sixties and seventies, knew cable and MTV were coming and that I’d be perfect for a twenty-four-hour music channel. So we knew this was going to be our secret weapon, that we could be on it, and that it was going to change everything.

And then came Rebel Yell, with Eyes Without A Face and Flesh For Fantasy close behind in support. How were you coping with becoming an idol, not only in name but now in actuality as well?

Pop stardom’s fantastic. You want people to hear your music and come to the shows. But I never thought of fame beyond just being a music person, of being on the radio and doing the occasional Top Of The Pops. MTV was on twenty-four hours a day, and it grew from an audience of a few million to countless millions all around the world.

Suddenly everybody knew who you were. And that’s a little weird. When I came to New York, I’d walk around and only the few people who were into punk rock knew who I was; now suddenly everybody did. And it was a big change that was really hard to deal with, because it cut off your freedom. I started to live in tiny little rooms, because when you walked outside you walked into a world of mayhem. And it drives you a little nuts.

So you start overloading on drugs. Because what else is there to do? So that was a problem. It didn’t help if you were a bit of a drug addict, and I turned myself into a bit of a drug addict at that point.

At the dawn of the nineties you had a major motorcycle accident in which you nearly lost a leg. What effect did that brush with death have on your attitude to life?

That’s what Bitter Taste, on The Roadside EP, is all about. It’s me reflecting back on this accident: was it something terrible, or was it something really good, where I took stock of everything and started to realise that I had to take control of myself in terms of the drug addiction?

And I did start, but I didn’t really start to gradually pull back until ninety-three or ninety-four. It took me a long time to come to terms with the drug addiction, to get it under control and get a sense of discipline, because there was no real control. Nowadays, I’ve taken back control and I’m much happier because I’m back to being me.

Appearing in the 1998 film The Wedding Singer compounded your iconic status. Would you have liked to have done more acting?

Well, I was in The Doors movie [’91]. I originally had a good part, Michael Madsen’s part [as Tom Baker], but I had that motorcycle accident. I probably should have got into acting a lot more, but it took me a long time to get control of myself in terms of drug addiction.

Do you ever feel trapped by who you are in the minds of your audience and beyond? After all, you’d have to think very hard about changing your hairstyle.

Yeah, but it’s still fun. I’m working with great people: [Green Day producer] Butch Walker, [songwriters] Sam Hollander, Tommy English and Joe Janiak. We really enjoyed making the EP, and playing the songs live has been great. Especially after the coronavirus. The audience are really getting into it, things seem even more alive than ever, and that’s incredible.

So it’s wild to still be here doing this, it’s been fantastic and the rewards have been great. We had to go through that time of MTV when it was all crazy, but now I’ve got the best of both worlds. I’m known, but I’m left alone now, so I can observe people. And songwriting’s all about observing other people and yourself.

In 2018 you worked again with Tony James, this time with Steve Jones and Paul Cook as Generation Sex.

Yeah, it was lovely getting back together and doing those gigs. We’re hoping to do a tour in England and Europe in 2023.

How difficult was it to discipline your children when you’re universally emblematic of misbehaviour, of giving the finger, the sneer: great in a rock video, but possibly not so much at a PTA meeting?

Yeah, but in the eyes of your children you’re not Billy Idol, you’re dad. But yeah, true, that would have been difficult. But they do have mothers as well, and extended family, so it’s not just about me. I think I’ve got a lovely relationship now with my children, and it’s great. My daughter’s pregnant with my second grandchild, my son’s got his music and seems to be enjoying that. And that’s all I want for them, to be enjoying what they’re doing.

What’s the greatest life lesson rock’n’roll has taught you?

That your dreams can come true. We dreamed of doing something artistic as a life choice, and punk rock gave us a chance, so we grabbed it. Which is incredible. Really lucky.

You benefitted from great timing, but would you recommend the same lifestyle choices you made yourself to kids of a similar age now?

We did it for love, and we were lucky to have enough success to go on. It may not work for everyone, but that’s the only way to approach music. If you’re doing it because you love it, it makes the hard times easier. We never did it for money or fame, we wanted to be in a musical movement that changed things, that affected society, that spoke about young people’s problems.

We wanted to have a gravitas, we did it. We found the right combination of people, and it worked. We got our dream… Incredible.

The Roadside EP is out now via Dark Horse Records. Billy Idol’s European tour commences in Glasgow on June 11. Tickets are on sale now.