Billy Idol is back, almost 12 years after he released his last studio album, Cyberpunk, and then abruptly disappeared. He only intended to take a rest, but it went on so long that it seemed he’d retired from recording forever.

Privately, Idol was grappling with problems. He suffered a drug overdose, and he lost his way after seeing the rock world turned upside down by grunge while he, in LA, was slowly suffocating in a record industry more interested in his earning potential than in his creativity.

Billy got on his bike. Roaring along the open roads of the American countryside, he felt the healing begin. But it would not be complete until he had accidentally rediscovered the exhilaration of performance, gone back to basics with a belting new band and a club tour, and negotiated a three-album contract with Sanctuary, a label he says has offered only encouragement.

Now Billy Idol is back with Devil’s Playground, a riveting collection that finds him doing what he does best, inimitably.

Today he’s dressed in black – even his tinted glasses have thick black rims; the spiky, bleach-blond hair is as bright as ever. Chains dangle from the waistband of his pants, he’s festooned with clumpy silver rings and bangles. And he carries it all off with the charisma of someone who has every right to look like this: a punk pioneer turned MTV hero turned easy rider turned homecoming king.

Sitting down to a bottle of water in a private corner of London’s plush Landmark Hotel, he’s lean, healthy and confident enough to wear his lifelines on a less than Californian-smooth complexion.

He’s alternately thoughtful and excitable, raising his voice while his words rattle out at a furious pace. Sometimes he jumps up from the sofa, gesticulating wildly, and, best of all, he frequently, loudly, bursts into song with the odd curl of his top lip: the sneer.

He’s immensely proud of his band, in which he is reunited with guitar wizard Steve Stevens and producer Keith Forsey. And as usual he talks in the third person about Billy Idol – his own creation, the leather-clad love god who can get away with anything and everything in the name of rock’n’roll.

He is, of course, everything you would have hoped. William Broad was born in Stanmore, Middlesex, in 1955, and even as a youngster he was quite a hit with the misses. According to his press biog, he lost his virginity at 11 to the strains of Tommy James & The Shondells’ Mony Mony (Naughty porkie; Mony Mony was released in 68 – eagle-eyed Ed.), and in 1967 he was kicked out of the Scouts for smooching with a girl.

His earliest experience of music came from TV westerns. “There was always some guy singing a song,” he remembers. “There were all these cowboy ballads.”

He starts crooning Do Not Forsake Me, Oh My Darling, from the movie High Noon, before leaping into Billy The Kid: ‘Way out in Mexico, long long ago, when a man’s only chance was his own .44…’

Then there were the dramatic solo singers. “Matt Monro was huge,” Idol says. “Born Free…, I thought if he could do it, I could do it.”

In 1975 William Broad quit Sussex University, moved to London and soon became one of the Bromley Contingent, a group of Sex Pistols followers that also included Siouxsie Sioux and Steve Severin.

He changed his name to Billy Idol, and formed Generation X with former Chelsea bassist Tony James (later founder of Sigue Sigue Sputnik).

He and James, with various drummers and guitarists, played an urgent, poppy brand of punk across three albums – Generation X, Valley Of The Dolls and Kiss Me Deadly – and had a string of hit singles. At the same time, Idol and his girlfriend Perri Lister became a fêted couple.

After leaving Generation X and relocating to New York, he experimented with dub mixing, teamed up with guitarist and co-writer Steve Stevens and producer Keith Forsey, signed to Chrysalis, and released his debut solo album, Billy Idol, in 1982.

Idol’s defection to America wasn’t popular in Britain, particularly when he started appearing on the recently launched music channel MTV.

“I can understand why people would feel resentful,” he nods. “But they didn’t know what it was like. I couldn’t get my records played on American radio; they didn’t like people with spiky hair. The record company took my picture off Hot In The City and it got on the radio, and it got to number 18. Then I put out White Wedding, and they wouldn’t play it.

“I saw MTV as a platform, that’s all. It was another way to get my music across. But I was ‘poor little Billy Idol’. Some people had two million dollars to put into videos. I’d come up with my daft ideas, trying to work with decent people on a shoestring budget.”

Idol admits to a certain nostalgia for his earliest adventures in music at home and abroad: “It was a magical time,” he smiles. “I fell in love, we were being successful, or we were struggling to get our music on, or doing dub remixes, or trying to refocus Generation X energy into Billy Idol fuck music. Cherie [on the new album] is a love song to Perri Lister and going to Venice and Paris, and the humid New York summers. If ever I want [to recapture] that spirit, I can see it in our child.”

White Wedding eventually made the US Top 40 – and Billy Idol went platinum – and was followed by Rebel Yell in 1983. (The UK caught up properly in 1985, after the Vital Idol compilation.) Whiplash Smile in ’86 was an international smash, as was its lead single, To Be A Lover.

Now Idol was the golden boy of the 80s. He received Grammy nominations for his singing. And he scored his first US No.1 single with a live cover of his supposed cherry-popping soundtrack, Mony Mony, in 1987.

“In lots of ways it was fantastic. Just to see people getting so much out of the music,” he says. “In the midst of all the craziness, you’d see some really moving stories about someone who loved something about the music that’s stopped them doing something – ‘Man, I don’t know why, but your album…’

“Music is about saving souls, in a way. It gives you a lifeline. This album [Devil’s Playground] is a little bit, ‘How do you fix a broken soul? How do you fix a broken world?’ I turned to rock’n’roll for release.”

Appearing in The Who’s rock opera Tommy in LA and London (playing Cousin Kevin), Idol chanced his luck by moving full-time to California – without Steve Stevens.

“The pressure of being on the road, five years non-stop, just got to us a little bit,” he recalls. “We never had a massive blow-out. He went off to do his solo albums and I went to LA and carried on with my career.”

Idol also bought his first Harley-Davidson.

On the last day of mixing his next album, Charmed Life, he smashed himself up so badly in a bike accident that it took five operations to save his right leg.

Charmed Life, in 1990, did brisk business on both sides of the Atlantic, as did 1993’s Cyberpunk, but the effortless swagger of Idol’s previous albums seemed reduced, increasingly remote. And his major role in Oliver Stone’s biopic The Doors was downgraded to a smaller part – performed on crutches.

“I think it was crack,” Idol says of his overdose in 94. “I was doing a ton of crack. And I took pills to try and calm down.

“My son Will and my daughter Bonnie were going to be of an age where they could read the news. My daughter lived with her mother. My son was living with me week on, week off. I was taking him to school, dealing with teachers and parents, and I wanted him to have friends round to my house to play. The last thing I want them to see is: ‘Oddball Idol has gone crazy again’. I had a responsibility that was bigger than all the world.

“What do I want – to be a drunk with my kids, or a fuck-up? Maybe I wanna be cool. I want to be a dad.

“What saved me was this street heroin came out. It was so bad that even I thought: ‘This is terrible, this just sucks’. And my body was starting to get sick from drugs. I never got into shooting up, thank God. That probably saved my life as well.

“I was always a bit of a binge artist. I’m not fucked up all the time. I’m all right for a while and then, ‘Hey! Don’t fuck with me, I’m on a binge’. And that may have saved me too.”

While Idol has reassessed and adjusted his lifestyle, it’s a great relief that he has done so with balance, and not as the typical post-rehab evangelist. “I smoke pot and stuff like that still,” he confesses. “I have a drink every now and again. If I wanna go on a bender, I will.”

In the mid-90s, with grunge having swept the world, Idol was disillusioned and crushed by the corporate machine. “The music needed to regenerate,” he concedes. “But it didn’t need to be regenerated with a bunch of idiots who weren’t in love with what I wanted to do, telling me what album to make. That’s what I was coming up against. I thought: ‘There’s no point. What’s going to happen is that I’ll start chasing fashion, when I led fashion.’

“We tried to make an album, and it didn’t work. I was having trouble writing songs. You get down on yourself. I thought: ‘Fuck this, I’m taking a break. That’s 21 years I’ve been rocking non-fucking-stop.’

“This mate of mine, Stephen McGrath [now his bassist], he’s a long-distance motorcycle rider, and we started to do runs out of LA. You’re on this hog, this beast, going on forever. It’s a great way of seeing America. You go through all this beautiful country that I saw in cowboy movies. You feel like you’re in a Wild West Mad Max movie.

“You get very meditative on the bike rides. You start fixing things in your brain. ‘What do you do to go forward?’

“One of the great things I’ve always wanted to do is go on a run which happened to end up on a stage somewhere. There’s a redwood run which goes to the top of Washington state. You can do it in a weekend. And they had a stage at the end of it with all these blues bands.

“Los Lobos turned up. I went: ‘I know half of those songs. Fucking hell, I’d love to sing’. I was at the side of the stage…”

He re-enacts his frantic mime to Los Lobos: “Can I come on?” They responded: “‘Train Kept A-Rollin’?”

“I was spinning, gone with the music,” he whoops, leaping up and whirling round in circles. “I looked out and suddenly I saw a whole lotta women and bikers going crazy. It made me think: ‘Man, you can still do it’.”

Between 1994 and 2001, Idol wrote for, and acted in, a number of films, but musically he ventured out on the road only once, in 1996, with the production of The Who’s Quadrophenia.

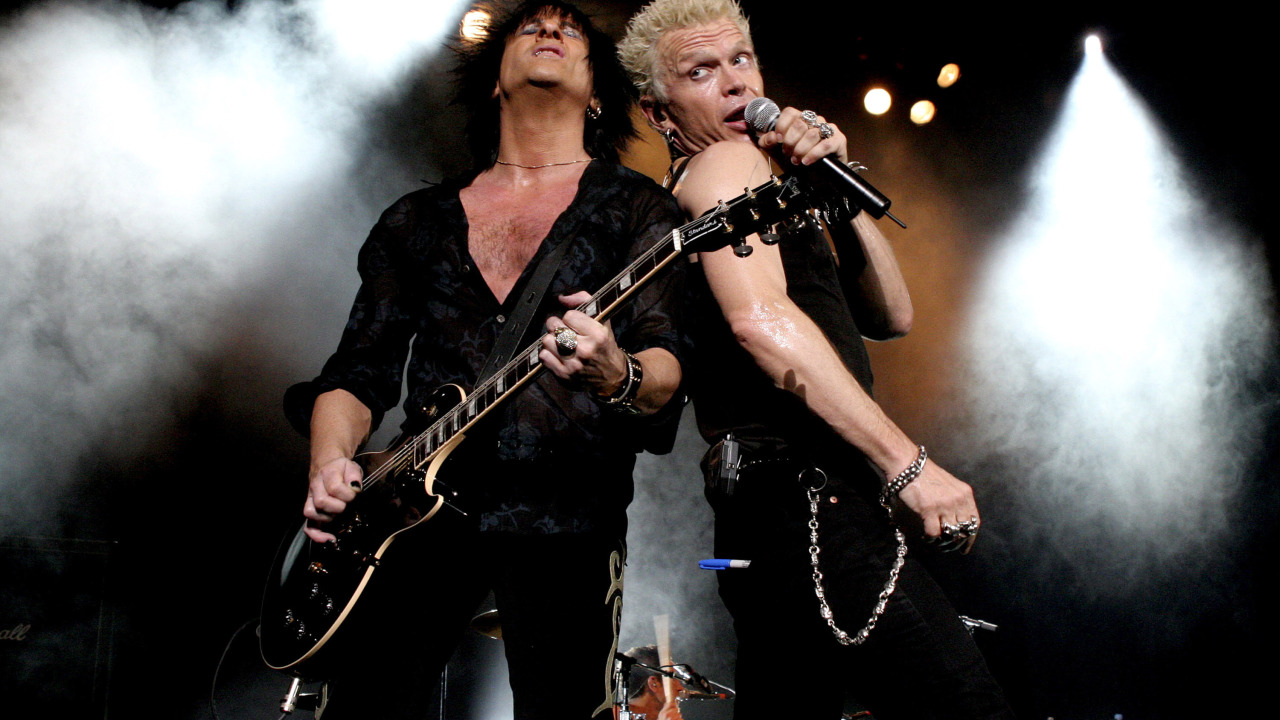

With more than a million sales of Greatest Hits in 2001, the scene was set for Billy Idol’s return. Performing at MTV’s 20th-anniversary show, he was showered with compliments by the likes of Snoop Dogg and Run-DMC. Then he went on a tour of clubs and small theatres with his old collaborator Steve Stevens, his biking buddy McGrath, drummer Brian Tichy (ex- of Slash’s Snakepit) and keyboardist Derek Sherinian. And the tour never really ended.

“I had a drummer, this young guy, kicking my ass,” Idol laughs. “I had people who were helping to push the limits of what I do.”

As the band became tighter and more dynamic, Idol began writing new songs with Stevens and Tichy. They sounded fantastic. So when Merck Mercuriadis from Sanctuary showed up at a gig in New York and asked the right question – “Will you make a great Billy Idol record?” – they already had material written and were quick to “blast it down”.

“Now I can say I made an album for the right reasons,” Idol insists. “I hope it’s the best since Rebel Yell. It’s like a massive throw of the dice. I’ve put my future on this. I won’t starve, ’cos I can always play live, but me, Steve, Brian – everybody who is making Billy Idol music – I want to extend what we’ve done and go on.

“With this album, I wanted the energy of Generation X and the attitude of Rebel Yell, and I wanted variety.”

His new album, Devil’s Playground, tells the personal and musical story of Billy Idol, incorporating all his influences. He describes it like this: “The full rockaBilly Idol to punkaBilly Idol to heavy metal-a-Billy Idol to Elvis-a-Billy, countryBilly…”

It’s an album of light and shade in both sound and subject matter, swerving from the dark days of heroin to the rocking hilarity of Yelling At The Christmas Tree.

“I did spend one whole Christmas screaming at the Christmas tree,” he says with a smile. “I was having an argument with my manager. Every time I put down the phone I wanted to continue the argument. The Christmas tree was glittering over there, and it was just the right height. [Acting out the confrontation] ‘I can break your balls! Come on, big boy. Come on!’.”

Equally light-hearted is Romeo’s Waiting: “We used to go to this place called the Star & Garter in the Valley in LA. One night I ended up going off with one of the birds who was on stage. It was like: ‘I saved her life from this den of iniquity.’ It made me think of a guy falling in love with one of the strippers. He’s like Lancelot the knight – the most romantic people in the world and the biggest losers. Then I thought: ‘That’s what Romeo was.’ And we love those losers. It’s a daft song. I didn’t want everything on this album to be like Cyberpunk, level-10 serious.

“The album moves from a World Coming Down to where you resurrect your belief in love and a future. It’s difficult, but you can work through the problems of life and keep smiling. The album itself is a sign that I’ve worked through all my problems. There wouldn’t be a record if I hadn’t. Super Overdrive is a call to arms – Billy is back and rocking!”

Does the Devil always have the best playgrounds?

“Yeah. We had the best music as well. Although it was always more playground than Devil for me. Now, the world’s got heavier, crazier. And although people don’t want to forget that, there’s a moment when they want to have a bit of fun and say: ‘Hey, make me scream, darlin’. I’m sick of the news.’”

THE X-MEN

Billy The Pre-Pop Star Punk

In 1976 Billy Idol (on guitar) teamed up with Tony James (bass) and Gene October (vocals) to form Chelsea. After only weeks Idol and James left to form Generation X.

On December 14, 1976, Generation X played at the first gig held at the Roxy Club in Covent Garden, the venue that would soon become a punk Mecca.

When the band signed to Chrysalis Records it was reportedly for the biggest advance given to a punk band.

When their first single, Your Generation, entered the UK chart at No.38 and the band appeared on Top Of The Pops, it was seen by many other punk bands as a sell-out. They became a constant target for criticism because of their polished punk look and a style of music considered to be pop, not punk.

In 1979, with new album Valley Of The Dolls, they had a Top 20 single with King Rocker.

While broke and fighting a legal battle with their manager, the band approached Bill Aucoin, former manager of Kiss. While negotiations continued with Aucoin, the band toured clubs, unable to release a new album because of the ongoing legal battles.

Guitarist Derwood (Bob Andrews) left the band, which prompted Idol and James to ask drummer Mark Laff to leave as well because it was felt the music was starting to take on an undesirable heavy metal feel. The new members were Jamie Stephenson and original Clash drummer Terry Chimes.

In December 1980, Billy Idol parted company with Gen X (as they were now known) and headed off under the wing of Bill Aucoin to launch his solo career.

SHEER CHART ATTACK

Billy’s Solo Hits

Hot In The City – #58, Sept ’82

Rebel Yell – #62, March ’84

Eyes Without A Face – #18, Jun ’84

Flesh For Fantasy – #54, Sept ’84

White Wedding – #6, July ’85

Rebel Yell (reissue) – #6, Sept ’85

To Be A Lover – #22, Oct ’86

Don’t Need A Gun – #26, Mar ’87

Sweet Sixteen – #17, Jun ’87

Mony Mony (live) – #7, Oct ’87

Hot In The City (remix) – #13, Jan ’88

Catch My Fall – #63, Aug ’88

Cradle Of Love – #34, April ’90

L.A. Woman – #70, Aug ’90

Prodigal Blues – #47, Dec ’90

Shock To The System – #30, Jun ’93

Speed – #47, Sept ’94