“I’m trying to get out of the rescue business, man, but it’s hard to quit.”

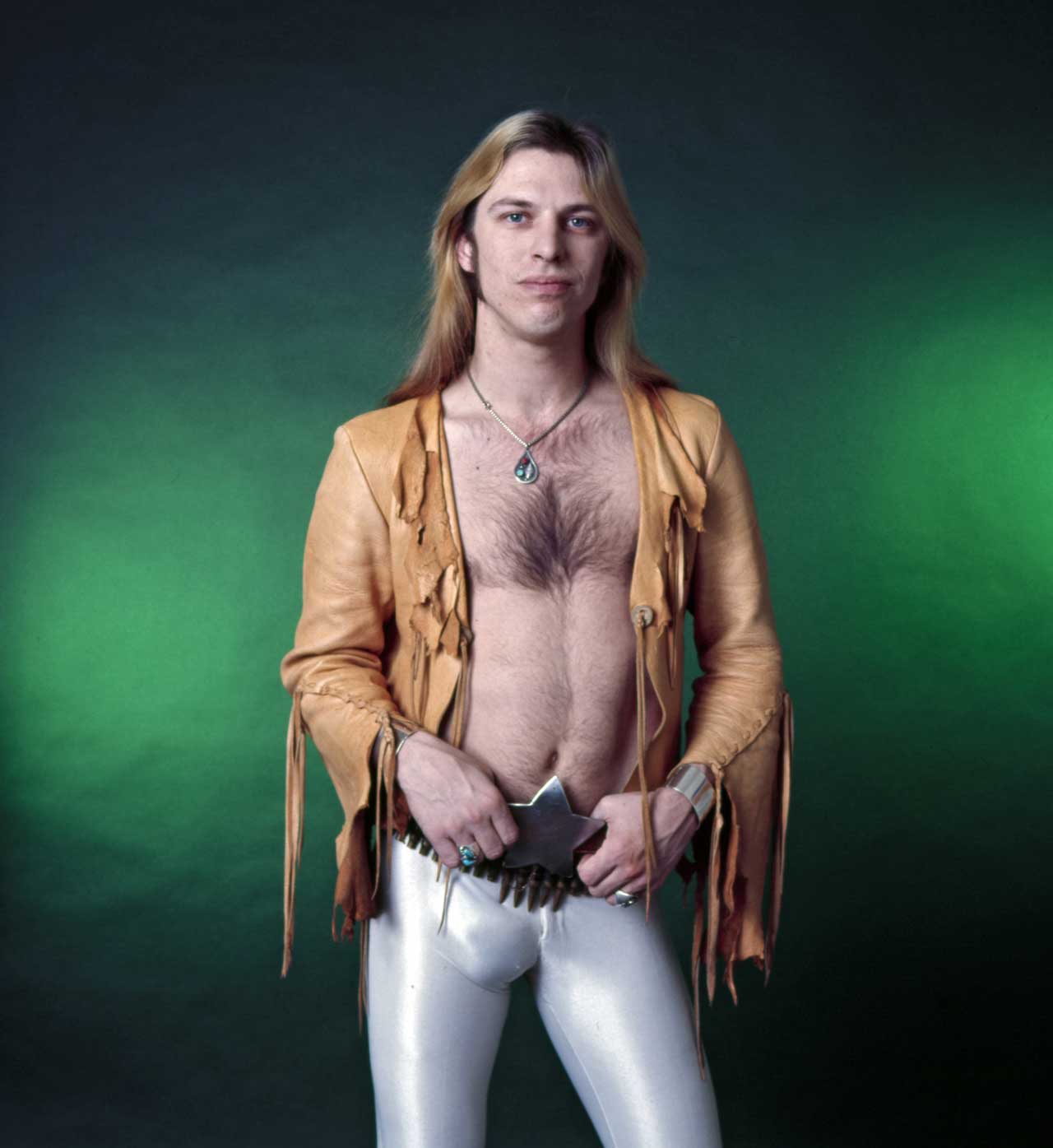

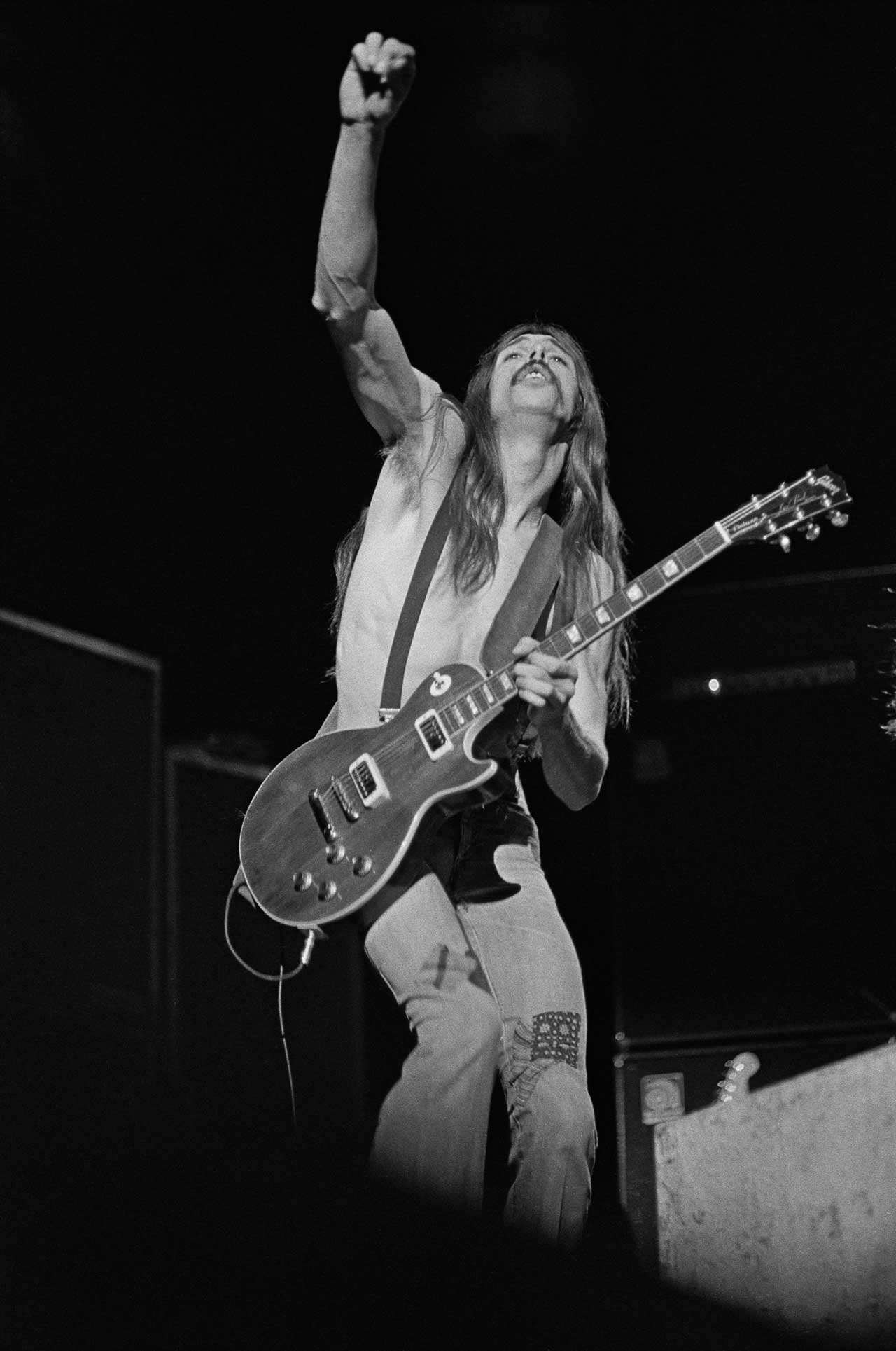

Jim ‘Dandy’ Mangrum is the last of the rock’n’roll superheroes. Still clutching his bullet-proof washboard, still clad in white leather and with flowing blond mane, the man who invented southern rock in the very southern state of Arkansas back in 1965 has weathered every bad season, overcome every obstacle, and bested every cheating ratfink and politician that has crawled his way. In their 40-plus years in rock’n’roll, Jim Dandy and his league of gentlemen in Black Oak Arkansas have gone from teenage outlaw hippies to authentic rock gods with gold records and stadium tours, with every rags to riches variant in-between. They may not have their private compound in the Ozarks or an army of roadies anymore, but integrity, spirit, and gumption – that, they’ve still got plenty of.

“See, I was friends with Bill Clinton since before he was the Attorney General, back when he was mayor of Hope, Arkansas,” says Jim Dandy, by way of introduction. Indeed. But wait – what of the scurrilous rumours that Jim Dandy and the former US president smoked marijuana together?

“I smoked with him, yeah,” Jim laughs, “but we didn’t inhale!”

Ho ho. You get the picture. Jim Dandy is larger than life and weaves his tales of rock’n’ruin with mentions of many guest celebrities – Elvis looms large, as does John Lennon, and a host of southern politicians – but the man that comes up the most is his co-founder in Black Oak Arkansas, Rickie Lee Reynolds. The two met in junior high and were, as Jim sees it, fated to play together. After all, they were the only two men in all of Arkansas with long hair.

Rickie Lee lived in neighbouring Monette, two miles from the tiny town of Black Oak, Arkansas. Jim had to attend high school in Monette because Black Oak was – and is – too small for a high school of its own.

“My mom and dad are still alive and they still live there, on Main Street, right across the street from the post office,” Jim beams.

“The population of Black Oak is 282 people, and it never changes, Rickie Lee adds, “Because every time a baby is born, the father leaves town.”

Influenced by The Beatles and The Byrds, Rickie Lee took up the guitar. Jim Dandy, well, he already knew what he wanted to do.

“When I saw Elvis on Ed Sullivan, I knew he was having more fun than any other human being up there. He was having cosmic fun, and I wanted to do it, too. I didn’t want to be no rock star, when I was young I didn’t even know what that was. I just wanted his job, whatever it was.”

Both men had their own bands, until one day when Jim pointed out that they were the only worthwhile components of either group.

“We just naturally bonded and watched each other’s back,” says Jim, “And we’ve been together ever since.”

In 1965, Jim and Rickie Lee found some other brave souls to form a psychedelic rock band called the Knowbody Else. Their first obstacle was a lack of proper gear.

The solution? Steal it.

“We broke into the high school and stole some speakers and the power amp,”

Rickie Lee explains. “Our parents were all poor, so we couldn’t afford that stuff ourselves, and they had this old PA system that wasn’t being used at all, so we went there in the winter time and snatched that critter. We got caught for it and had to give that back – and buy a new one to boot.”

Crime didn’t pay, so the Knowbody Else was forced to do things the hard way.

“We all moved into one house and started sharing expenses,” says Rickie Lee.

“All the money we made went into the band, with just a little bit left over to eat. So at the end of the week, we had a little money left to buy a whole lot of one thing. One week we’d buy potatoes, so every meal we had was potatoes. One week we’d eat eggs, one week we’d eat popcorn. The rest of the money we’d use to buy equipment. We’d also have girls that would snatch food from their mom’s fridge and bring it over to us because they thought we were hungry. We were farm boys, so we knew how to get by on just a little bit.”

Fuelled by starch and nubile farm girls, the band began to hone their craft, a sort of southern-tinged cosmic boogie laced with a healthy lust-for-life and, well, just plain lust. No longer schoolboys, the Knowbody Else learned early on that for diehard rock’n’rollers, it’s best to keep moving.

“We headed up to Lake Norfolk, they had some caves up there along the ledge,” Jim explains.

“We didn’t stay in ’em, though. We only stayed in the cave about one night. They had bats in there. But we did stay up there for awhile. That’s because that was after my first marriage, and I was behind on my child support. That’s the only time I ever had to go to jail, too. Not then, but a month or two later. We went down to New Orleans to stay out of trouble and we went from the pan to the fire.”

“When we got down to New Orleans we found a club there called the Gunga Din,” says Rickie Lee. “We played there for over a year every night. We started at 7pm and we’d play until 6am, half-hour on, half-hour off. That was 365 days a year. We got to know New Orleans pretty well.”

“That all started when the crops came in,” Jim explains.

“You know, in mountain territory they work around the harvest, and they let you out of school early. So when I came back I had long hair because we had a good crop that year, and my dad said, ‘I don’t care how long you grow it, as long as you keep it clean.’ So I got back to school and realised I was in a fix, because here I was on monkey island and here I was with the other monkeys and they got weird because I didn’t look like them.

“I bin in more fights than anybody besides Wild Bill Hickok. I’d get into fights every day behind the barn after school because of my hair.”

“Jim would get called out all the time,” guitarist Rickie Lee remembers. “So he ended up in a lot of fights. He didn’t always get beat up, though. Sometimes, he’d do the beating.”

“Anyway, that’s when it all started,” says Jim. “It was just me until Rickie Lee came back from California. He had long hair too, by then. A surfer cut, after Brian Wilson, I guess.”

“I was born in Arkansas, but my dad was a carpenter,” explains Rickie Lee. “So we had to go where the work was, and I grew up in California. I had long hair out there and when I came back to Arkansas in the 10th grade, my hair was three times longer than anybody else’s, except for Jim.”

At the same time, the band was searching for a record deal. They had already released one album in 1971 on Stax records, an all-black label from Memphis, but being white and psychedelic did not help their cause.

“The radio stations would get records from Stax, and it’d be Otis Redding, Isaac Hayes, the Bar-Kays, and then all of a sudden you’d get this white psychedelic band, and the DJs would go, ‘What the hell is this?’” laughs Rickie Lee. “So Stax, even though they treated us real well, didn’t have a market for our kind of music.”

The band started to split their time between New Orleans and California, where they thought their unique southern-ness might get them noticed.

“We were out in California playing these outdoor festivals,” says Rickie Lee. “It was during the free love era, and you’d have half a dozen groups all out in Griffin park playing that afternoon. There’d be 4,000-5,000 people out there, all getting high and weaving blankets with their babies and their monkeys, and it was just a big carnival.”

Their cunning plan worked, and the band soon signed a lucrative contract with Atlantic Records.

“Well, we’d put out our first Atlantic album, and we were doing really good,” Rickie Lee remembers. “There was no other group doing that kind of music then. We were the first ones to have the three guitars, the first to mix up rock, country, and rhythm and blues. We got a major agent in New York who was gonna book us, and Iron Butterfly were doing a farewell tour at the time, they were going to break up. So they did a national tour and we got on a bus and opened up for them, and when we came back, it was time for Grand Funk Railroad to break up, so we got their break-up tour, too.

“Those guys were huge back then, they were playing arenas, and they didn’t even advertise the opening acts. But by the time the tour was through, everybody was talking about Black Oak Arkansas. It was like, ‘I saw Black Oak Arkansas! Oh yeah, and Grand Funk were there, too.’ For three years in a row, we did 321 nighters per year, and two albums per year. We were never home.” By the end of 1972, things were looking very good for Black Oak Arkansas. And that’s when the trouble started.

“I’m only five foot nine,” Jim says. “People always say, ‘I thought you was taller, Jim Dandy.’ I tell ’em, ‘I used to be bigger, until they took all my money away. And when they give me my money back, I’ll be big again.’”

- The History Of Southern Rock In 30 Songs

- The story of Captain Beyond, stoner rock pioneers

- Sir Lord Baltimore: "We were the first band to be called heavy metal"

- Rock'N'Soul: 20 Soul Classics Rock Fans Will Love

If there is one taboo subject in the Black Oak ranks, it’s money. Throughout the 70s the band rose a crest of unparalleled success.

“On paper it looked good,” says Ricky Lee. “We had a full road crew, we had a business manager back home who was hiring all these people. We donated three-quarters of a million dollars in charities to the state of Arkansas. We replaced the last one-room schoolhouse in Arkansas, we helped build a radiology wing in a hospital, we gave money to mentally retarded children and the YMCA, we got a letter from Betty Ford for our contributions to the American Cancer Society, battered wives… We donated a lot of money back then. So as much money as we made, we gave a lot of it away. We had our bills paid, but we never saw a great fortune.”

“But then, without even talking to us,” Jim says, “Our manager decided to send us to this lodge…”

Ah yes, the infamous Black Oak compound. Now a thriving 6.5 acre resort on Bull Shoals lake, from 1973 to 1978 it was the home of the entire Black Oak organisation, an idyllic mans-world of hunting, fishing, and hard rock.

“They dammed up the river and made two lakes,” says Rickie Lee. “It used to be a hunting and fishing lodge. There was a big main house in the middle that had a café and stuff in it and it had four or five cabins all around it. We found that everybody living together was cheaper than a dozen people all living in separate places. So we lived in that compound until ’77 or ’78.

“We loved it, but our old ladies hated it. There was nothing to do. You had to drive 25 miles to get to the nearest movie theatre, and if you had to go to the hospital you were looking at a 150 mile trip. It was way out there in the Ozarks. But we had great hunting and fishing. All the stuff guys like to do was right there, and all the stuff girls like to do was hundreds of miles away. Plus, we’d leave the girls at the lodge and we’d be gone for a year on the road. It was really hard to keep a family going up there.”

By the end of the 70s, Black Oak’s popularity began to wane. Many of the bands they took on tour with them in the beginning – Lynyrd Skynyrd, Bob Seger, Bruce Springsteen – had gone on to major stardom, leaving Black Oak behind. It was time to regroup, pare down, get back to basics. And that’s when they realised their fortunes had dried up.

“We had a pretty good idea of where our money went,” says Rickie Lee. “Between me and Jim, we figured we’d lost several million bucks. It just disappeared.”

“I’m over it,” sighs Jim. “About 15 years ago I broke my back. Fell asleep at the wheel and hit an oak tree. In a dream, the good lord came to me and said, ‘You can have a good life again if you let go of vendettas and grudges and forget about the past,’ so I got over it, because I wanted to walk again. I didn’t want to be in a wheelchair for the rest of my life. It took something like that to really rattle my chains and get me to appreciate things.”

The 80s were lean times for Black Oak Arkansas, but Jim and Rickie Lee rallied with 1984’s Ready For Hell album. Marketed as a Jim Dandy solo album, its guttural sex-boogie sound charmed a new generation of Black Oak fans, and although they never managed to restore themselves to stadium-rock status, they found a niche that they still happily occupy: as America’s favourite biker band.

“For a long time, when the whole disco thing died down, we found ourselves playing at Sturgis, the big biker rally,” says Rickie Lee. “And they’d go crazy when we played Hot Rod or Hot N’ Nasty, they just loved that stuff. And all of a sudden, after years of this, we found ourselves doing a dozen biker gigs a year. The two biggest biker bands are us and Steppenwolf. They’ve got Born To Be Wild and stuff like that that relates to bikers. I’ve never been able to put my finger on why they like us so much, but we love it.”

For the past two decades, Black Oak has been touring regionally in the southern US. “We do the weekend warrior thing, mainly,” says second-generation Black Oakster Hal McCormack. “Biker rallies, fairs, corn dog sucking things. The bikers keep us alive, Black Oak has got diehard fans that never forget. Thank god for that.”

Arkansas-born guitarist Hal McCormack joined Black Oak in 2000. The quintessential rock’n’roll journeyman, Hal’s played with Survivor, Tora Tora, and southern rock supergroup Deep South, among many others. But Black Oak, that he did not expect.

“Jim saw me playing around town in Memphis, and he said, ‘Whenever your band breaks up, give me a call’. So I called him,” Hal says.

“I saw Jim on Don Kirshner’s Rock Concert when I was 10 years old. I remember thinking, ‘Man, that dude is crazy!’ I never thought I would actually be playing with him.”

Hal is currently co-producing a new Black Oak album with Jim. When it’s released, it will be the first new Black Oak Arkansas album in decades.

“It’s called Memphis Mean Times,” Hal says. “It’s finished except for the mixing and mastering. It’s got 10 years of Jim’s writing in there, and every song is a fuckin’ novel. It’s not verse-chorus stuff, every song is like a story, and the songs all flow together. It’s a conceptual sorta record. This will be the first fresh Black Oak record in 20 years.”

The band are currently shopping around for a label to release it, and hope to have it out before the end of the year. In the meantime, there are still wrongs to be righted, and, as their most famous song goes, Jim Dandy will continue coming to the rescue.

“They threw me out in the jungle, expecting the animals to eat me,” Jim says.

“But the animals liked me. And I could have gotten the elephants to stomp on their village, but I didn’t. That’s not what I’m about. See, rock’n’roll has a meaning. It’s about freedom. And it’s about taking time to party. No matter what’s happening to the world, we’ve got to laugh and smile and face disaster. We can’t let it show, no matter what they do to us.”

And with that, Jim Dandy is off in a flash. Somewhere out there, a southern damsel is no longer in distress.

This feature originally appeared in Classic Rock 125.

The Top 10 Cult Southern Rock Songs according to Johnny Van Zant