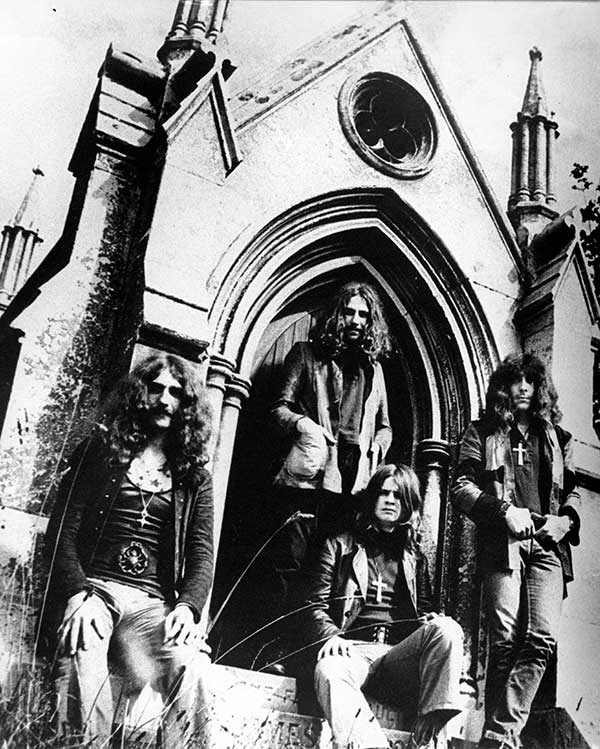

They were scum and they knew it. Human debris from the shitty, bomb-cratered streets of a post-war British nowhere named Aston. Or as Ozzy Osbourne would tell you, not a trace of a smile on his melancholy jester’s face: “We were four fucking dummies from Birmingham, what did we know about anything?”

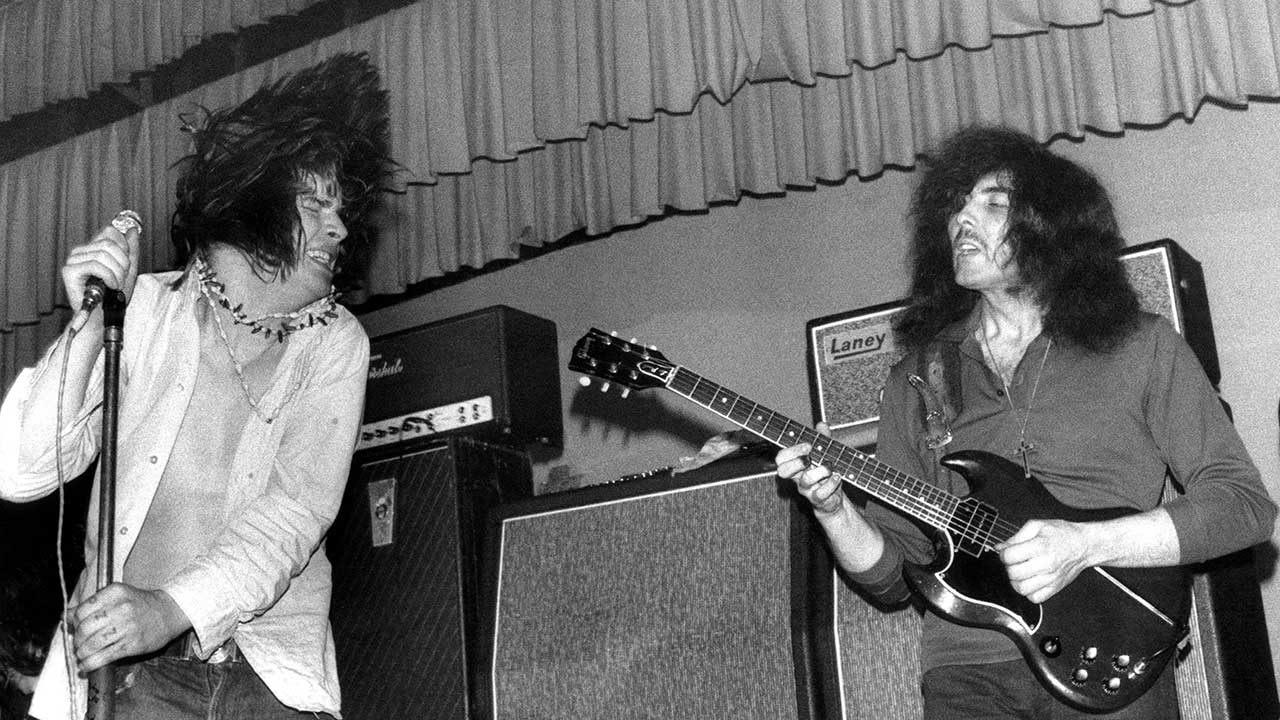

It turned out they knew just enough to change the world. Those crucifixion guitar riffs, nailed in with such heavy relish, framed by storm-gathering bass and head-rattling drums, together making a sound like that of a body being dragged from a river.

Those eerie singsong vocals, as dramatic and pitiful as the sound of a swan dying. Full of cobwebbed yearning, of self-harm and picked scabs and the shriek of lost souls.

The three of them zombie-walking around the stage in their preposterous crosses and moustaches, while the fourth self-combusted at the back, mouldering in his own poisons, the quad combining to ensure a fifth element: the pockmarked face of the most brutally deformed style of rock ever allowed to push its way, stinking and blood-cowed, among us.

They emerged from the shattered fragments of several local Brummie bands. By the time they were ready to begin rehearsals, a sax player named Alan ‘Aka’ Clarke had also somehow been added to the gang, plus a second guitarist, Jimmy Philips, and they had a new moniker: the Polka Tulk Blues Band – a name filched from a shop in Handsworth, according to Geezer Butler.

“It was on our way to our first gig. We passed this shop, the Polka Tulk, and I said: ‘Here, that looks like a good name.’” The Polka Tulk Blues Band lasted just two gigs: a caravan park in White Haven, and a ballroom in Carlisle. The first show ended abruptly when the audience of appalled caravaners began to get up and leave after the first number.

The second show also ended badly, after a posse of local townsmen decided the band had been trying to steal their women, and set about them with bottles and chairs. “They absolutely killed us!” Geezer recalled. The police were called and duly arrested the attackers, but not before their ringleader – “a massive, massive great big bloke!” – had strangled one of the police dogs.

Tony Iommi: “I thought, ‘Oh fuck. That’s it now. We’re not gonna get any work’.” Exit the sax player and second guitarist. “They’re going. They’re on their bikes,” Tony announced.

The other thing to go was the name, now changed to the Earth Blues Band, a mouthful quickly shortened just to Earth. Still relying on the same musical stew of blues covers and psychedelic workouts, “doing the same song over and over, just varying the tempo a bit,” as Tony put it, when he was offered the chance to replace original guitarist Mick Abrahams in Jethro Tull, and jumped at it. Then regretted it immediately.

Invited to London to begin rehearsing, Tony was so freaked out that he talked Butler into going with him. “I’d say to him: ‘I don’t know, Geezer, it feels funny to me.’ And he’d say: ‘Well, just stick with it a bit longer.’ So I tried it for a few more days, and I said: ‘Ah, I just can’t stand it. It’s not working for me’."

Travelling back to Birmingham in the van on Friday, December 13, 1968, Tony told Geezer: “Let’s get back and fucking get some work done and rehearse, and let’s do this ourselves, you know, and make this happen. We can become big, like Tull, but let’s get cracking.”

Earth picked up a manager in local music biz figure Jim Simpson, and opened for such acts as Locomotive and Bakerloo Blues Band, and occasionally headlined at places like the Bay Hotel in Sunderland, where support was provided by Van Der Graaf Generator and Radio 1 DJ John Peel.

There was even their first overseas gig, at the Brøndby Pop Klub in Denmark in February 1969, followed in August by a residency at the same Star Club in Hamburg where The Beatles had cut their teeth as live performers just a few years before. The big career turning point came with the first fully fledged original number they came up with. Title: Black Sabbath.

“At the very early part of Earth, we were still doing a lot of improvisation,” Bill Ward recalled. “The first indication of what started to emerge from these improvisations,” said Bill, came from their cover of a song called The Warning, originally by Aynsley Dunbar’s Retaliation, to which Earth now added an extended guitar, bass and drums workout. This began to take on monstrous new proportions during the Star Club residency, where they were required to play four 45-minute sets a night.

“We used to have to stretch the songs out, because we’d get bored doing the same six songs or whatever,” said Geezer. “For the jam after Warning, Tony would do this big, long solo and we’d all, like, join in, and eventually that became some of our first songs.”

The first to emerge, which they gave a title to, was a bombastic rock Frankenstein they entitled War Pigs. “It started out almost forty minutes long. Then we started shaping it into other songs too. Most of the songs on the first two Sabbath albums came out of those jams at the Star Club.”

The defining moment that turned Earth into Black Sabbath occurred one day at rehearsals. “I was listening to Holst at the time, The Planets suite,” Geezer recalled, “and I loved Mars.” He began to hum the lumbering, dramatic opening stanza. “I was playing it on my bass one day, and Tony changed it a bit, and it went from there. It just seemed to write itself.”

This was more than just an accident. The distorted riff that Tony came up with may have begun in seesaw emulation of Holst’s masterpiece, but the skeleton of the final riff – E, octave of E, B-flat – was based on what practitioners of the black music arts know as the triton, or diabolus musica, the most toxic interval in music, equating to half an octave, that so disturbed the church orthodoxy in the Middle Ages that it was instantly branded “the devil’s interval” and outlawed throughout the land.

Tony has always claimed he knew nothing of this when he first played it on the guitar to such shattering effect that day, but admits he felt “something was moving me to play like that”.

The title Black Sabbath – which appears nowhere in the lyrics and was only added later – was lifted from the 1963 Mario Bava film of the same name, aka Three Faces Of Fear, starring Boris Karloff. The lyrics – one of the few Sabbath verses that Ozzy had a hand in – described a particularly ‘black’ experience Geezer had recently had at his flat late one night while lying in bed.

“I was getting into black magic and the occult at the time,” he told me. “I just, like, had a morbid interest in it. I was reading every book that came out about it. There was one called Madness & Magic, which was like a monthly magazine that you collected.”

Described by himself as “sort of a religious maniac when I was a kid”, Geezer had grown up collecting crucifixes, “[holy] pictures, and medals – I wanted to become a priest… I literally loved God.” By comparison to his strict Catholic upbringing, the subject of the occult “was all really intriguing – forbidden fruit, kind of thing, and as an impressionable kid I just got interested in it”.

When, however, he awoke one night to find some sort of apparition in his room – the ‘figure in black which points at me’ of the lyric – “it frightened the bloody life out of me! I woke up suddenly, and there was this like this black shape standing at the foot of me bed. I wasn’t on drugs or anything like that, and I didn’t drink in those days.

"And at that time I had like this one-bedroom flat, completely painted black, and I had all these inverted crosses all around the place and all these posters of Satan and all that kind of stuff. And this shape… For some reason I thought it was the Devil himself! It was almost as if this thing was saying to me: ‘It’s time to either pledge allegiance or piss off!’ And from that moment on, I just went off the whole thing.”

In the morning, he took down all the crosses and posters and later had the flat repainted orange. He also began wearing a cross. When, just a few days later, Tony turned Geezer’s thumb-heavy bass rendition of Mars into a genuinely thrilling rock epic, the lyrics he and Ozzy had made up about Geezer’s early-hours freak-out fitted perfectly.

The new song – the first the band ever wrote together from scratch – became a warning against the Satanism and devil worship they would, ironically, be accused of actually dabbling in, time and again over the years by distressed parents and their gore-thrilled offspring.

No one who heard the song’s death-rattle guitars, its lightning-forked bass and drums, its trembling vocals, ever asked for an explanation as to what it was all about. They already knew. As Geezer said, by then “all the love and peace thing had come and gone, the Vietnam War thing was happening. And a lot of kids were getting into all kinds of mysticism and occultism. It was just a really big thing at the time. Everybody was getting into it and reading up about it.”

They could relate.

The clincher came later that same day they wrote the song, when they performed it live for the first time, in April 1969, at a pub in Lichfield called the Pokey Hole.

“The reaction was absolutely incredible,” Geezer recalled. “In those days when we played everybody would be stood at the bar drinking, not really paying attention. But we played that and everybody just stopped dead… and listened. The whole place was in a trance. We finished the song and it just erupted, they went absolutely nuts! And we realised then that we were on to something and it was good.”

The Pokey Hole Blues Club in Lichfield, England was the first place we played the song "Black Sabbath" here is a link: https://t.co/4dPhdlj85u pic.twitter.com/ijSdnskJnWSeptember 11, 2018

They began trying to write more material in that same gloomy vein. Geezer: “We were all totally into different things, even musically. I was into Frank Zappa and the Mothers; Ozzy was into The Beatles; Tony and Bill were into their own things too. But the one common bond we had was a love of horror films and science-fiction stuff. And that was reflected in the sort of music we would now make.”

Some of their earliest attempts – like the chattering hyper-blues of Wicked World, from the US edition of their first album – were clearly rooted in the Earth era: maudlin repetitive rhythms enlivened by Tony’s tail-flashing guitar. Some of it, though, like the embryonic War Pigs, which didn’t surface until their second album, quickly evolved into showstoppers of an even greater magnitude.

To cement their newfound direction, within weeks they had also changed the name of the band – to Black Sabbath.

“Black Sabbath was just so different to everything else,” Ozzy recalled. “Naming the band after it seemed to change everything for us, overnight. I always did love that title. The only problem was all the bloody trouble it caused with the black magic stuff.”

The band made their first appearances as Black Sabbath during a return visit to the Star Club, in the summer of ’69. They were a completely different band now. And not just in name.

“We were like fucking pirates by then,” Ozzy cackled. “Everywhere we went, people went nuts when we showed up.”

Even more people would go even more nuts when the first, self-titled titled Black Sabbath album was released on Friday February 13, 1970. Even more people have continued to go even more nuts for the band ever since.

Fifty years after they first wrote their anthem, the name Black Sabbath is now synonymous with the invention of the most enduring, consistently popular and wickedly wonderful music the rocking world has ever known.

Sludge metal, black metal, stoner rock… those down-tuned guitars, pope-on-fire vocals, bulging-vein bass and artillery-fire drums have been called many things this past half-century. But for Ozzy, at least, Sabbath’s music has always been about just one thing: “Heavy fucking metal! And bollocks to all the rest.”