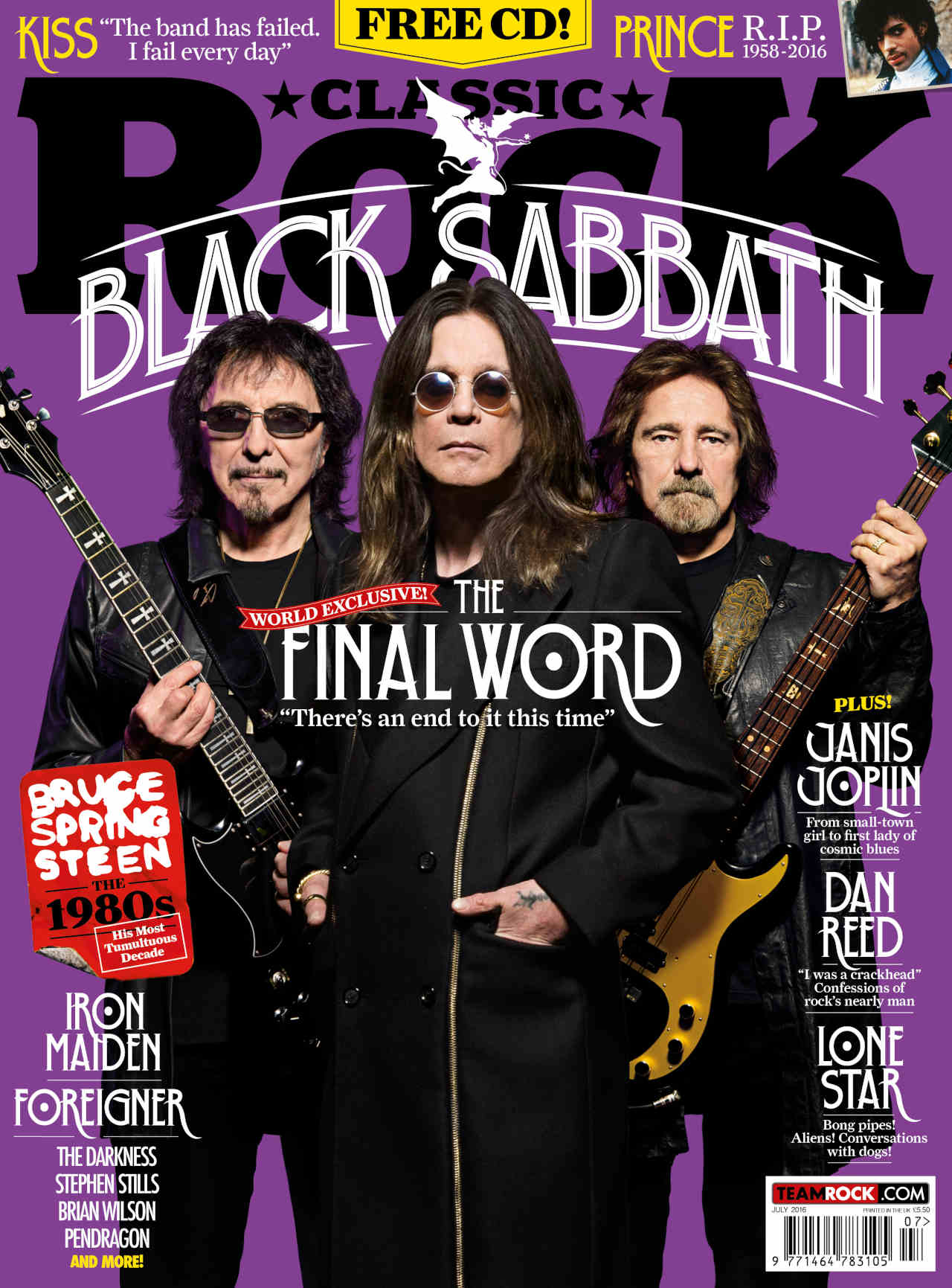

“Sabbath is the best thing that ever happened to me in my life. But everything has to come to an end”: The triumphant story of Black Sabbath’s last ever tour

In 2016, Black Sabbath’s The End tour reached Australia – and after a tumultuous career, the were finally ready to take their final bow

Black Sabbath were there at the dawn of heavy metal, but by 2016 the end of the road was in sight for the British icons. When Classic Rock joined the band in Sydney as they brought their farewell The End tour to Australia, we found a band ready to look back at their staggering legacy but unsure of what the future might hold.

Ozzy Osbourne has death on his mind. As a self-confessed hypochondriac, this isn’t unusual. But for once, it’s not his own mortality that’s bothering him.

“Fucking hell, man,” he mutters. “I just heard about Prince. Dead. The papers are saying he OD’d.”

His eyes widen behind his round, Lennon-esque shades. “Fuck me. It’s been a shitty year. People keep dying. Every other week some other c**t dies.”

He shakes his head, looking simultaneously rueful and befuddled in the way that only Ozzy Osbourne can.

It’s lunchtime in Sydney, Australia. A few hours earlier, the country woke up to the shock news of the Purple One’s death. The Grim Reaper has delivered another rabbit punch to rock’s already battered psyche. Lemmy, Bowie, Dale ‘Buffin’ Griffin, Glenn Frey, Jimmy Bain, Keith Emerson and now Prince. You can’t help wondering when it’s going to stop. Especially if you’re Ozzy.

“Lemmy, man,” he says. “That broke my heart. If someone was to say to me, ‘What’s your depiction of the heavy metal rock star?’, I’d say Lemmy Kilmister. He always said, ‘I’ve lived my life the way I want to. I may have been able to live to eighty if I hadn’t smoked, or drank Jack Daniel’s, or done speed, but fuck that.’ Saying that, I bet if he had a fucking chance to come back and be around for a few more years, he fucking would.”

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

The two of us are sitting on adjacent-but-one chairs at a polished round table in a tastefully appointed room in one of Sydney’s more discreetly upmarket hotels. From the ankles up, Ozzy looks exactly as you’d expect him to. Black T‑shirt, black trousers, thicket of hair framing those sunglasses, their purple lenses inadvertently appropriate today.

It’s only when you look down that the rock star illusion is shattered. Ozzy’s feet are stuffed into a pair of fetching blue and purple hotel slippers, which carry him around in that unmistakable hunched-over, sped-up shuffle. But then he is 67 years old, and if a 67-year-old can’t pad around in slippers, then who can? Especially one who has come close to dying more than once.

“Oh, fucking hell have I. Just ask my family. I’ve nearly died loads. I’ve had several stomach pumps, my heart stopped twice when I broke my neck on a fucking quad bike. Every time I got stoned and drunk, I didn’t get tipsy I got fucked. I haven’t drunk for three years, I haven’t smoked for twelve years, I don’t do drugs any time. It’s cool.”

So you aren’t planning on departing us yet?

He grimaces a cartoon grimace. “Fuck that. Sharon told me: ‘You’re not fucking going anywhere till this tour’s finished.’”

For Black Sabbath, matters of age and death are more pertinent than they’ve ever been. Their current world tour, bluntly titled The End, is billed as their swansong. Just as the five dates they are playing i n Australia will be their last time in this part of the world, so their headlining slot at the Download festival on Saturday, June 11, 2016 will be their final appearance in the UK.

As it stands, when the tour ends in Brazil in December 2016, Black Sabbath will cease to exist. Thank you and goodnight, that’s your lot. Would the last one out please turn off the lights. And you don’t know it yet but, like Lemmy, like Bowie, like Prince, you’ll miss them when they’re gone.

If anyone is holding up their hand and taking the blame for the end of Black Sabbath – or at least this final tour – then it’s Tony Iommi. The guitarist was diagnosed with lymphoma in 2012. While initial treatment was successful, he’s still locked in an ongoing battle to keep the disease at bay.

“It was possibly me that started it all off really,” he admits of the decision to wind up Sabbath, “which feels even worse because I didn’t want to stop the momentum of everything. We were presented with a tour, and I spoke to my management and the doctors and all the rest of the stuff, and I just had to be sensible about it. That’s it for me doing these extensive tours.”

Where Ozzy is everything you imagine him to be, the reality of Tony Iommi is a world away from the myth. While he still looks the part – head-to-toe in black, heavy cross pendant hanging on his chest, no carpet slippers here thank you very much – he’s no longer the glowering, dark-browed, monolithic figure who riffed, brawled and snorted his way through the 1970s.

“He’s changed so much,” says Ozzy. “He used to be the Darth Vader of the band. What he said went. But he’s got really humble. When you get something like cancer, it fucking shakes your tree.”

Today, in a Sydney hotel suite, Iommi is the perfect elder statesman: funny, measured, gentlemanly. He talks fondly of his bandmates (“We’re getting on great together”) and frankly about his illness (“I’ve been feeling okay, but I do have moments of getting shaky, anxiety, all sorts of stuff”). The only time he looks out of sorts is when I bring up the accusations made about him by Lita Ford, who claims in a new autobiography that Iommi had beaten her when the two were involved in a relationship in the 1980s.

“I’m not going to say anything about that,” he says. “I don’t even want to know about it. I’ve only heard about it…” Presumably he means via other people, but he won’t be drawn any further.

For Iommi, The End tour is the culmination of a 48-year journey that began in the sheet metal factories of Birmingham. While Ozzy’s public profile far outstrips that of both the guitarist and bassist Geezer Butler, it’s Iommi who carried the band’s name through the lean times of the 80s and 90s, accompanied by a changing cast of musicians.

“I’ve liked loads of the periods we’ve had,” he says. “But it was difficult, yeah. Frustrating. I won’t say it wasn’t. It was costing me personally, because I was putting the money in. Then when the records die or the shows die off, you have to think about what you’re going to do. These days people are more accepting of those albums than they were at the time. At the time, nobody knew we had these bloody albums out.”

Iommi admits that he kept an eye on Ozzy’s solo career during that period, though he doesn’t go so far to admit any jealousy at his former colleague’s stellar success. There were barbs exchanged in the press. “It was a bit sad, because it became an us-against-him thing,” he says.

All that came to an end in the summer of 1997, when Osbourne, Iommi and Butler reunited for the US Ozzfest tour. That was followed by two emotionally charged home-town shows at the Birmingham NEC Arena, where they were joined by original drummer Bill Ward.

This first reunion lasted until 2005, when Sabbath wound down for the second time. By 2010, they were back together for another round of touring and, more remarkably, an album, 13, which held its own against anything they released first time around.

Six years later, and close to half a century after they first staggered into the light, the wheel (of confusion) has turned full circle. For Black Sabbath, the journey is nearly complete.

“When I got into this, I never saw an end to it,” says Tony. “Which is weird, because now there is an end to it.”

Has the reality of Black Sabbath coming to an end sunk in yet?

Ozzy: Oh, yeah. It’s starting to.

Tony: I don’t think it has. It’s sinking in more here in Australia, because it’s the last time we’ll be here. But we’re going back to America and the UK.

Geezer: We’re playing harder and better than ever, because there’s an end to it this time, rather than going on and on and on. But I think it’s going to be sad when it finally happens.

Does this tour feel like a celebration? A victory lap? Or is it just another tour?

Tony: It’s a mixture of things. When you think about it, it’s sad because we’ve been together for 48 years, and we’ve known nothing else but touring and playing together. It’s really going to be a big wrench, but the end has to come at some point.

Geezer: Victory lap’s a good way of putting it. I know when me and Tony did Heaven & Hell with Ronnie [Dio], we always wanted to do one final Sabbath album, one final tour, which is why we thought the 13 tour was going to be the last thing. But the 13 tour wasn’t that long. When it finished we felt that we still had lots of places that we still had to go to.

So who made the call? Who said: “I don’t want to do this any more”?

Geezer: I think we all came to the same conclusion. It was on the 13 tour, and Tony was the one who mentioned something about how this could be the last one. Me and Ozzy were thinking the same thing, but we weren’t saying it.

What are you reasons for stopping?

Ozzy: We’re not getting any fucking younger. Every other day we’re seeing some other rock star pegging it.

Geezer: A lot of it’s age. We’re all aware of our mortality these days, especially with Tony getting cancer. We don’t want to fade out on the road. We want to go home and enjoy a bit of home life. We’ve been on the road for forty-eight years. It’s a long time.

Tony: For me, personally, since I was diagnosed it has changed my whole life. I’ve had to really think about it seriously. I can’t just pack a suitcase and go off and disappear around the world. I don’t want to go on and keel over on stage. [Laughs] If it’s going to happen, I’d rather be at home.

Whatever the future holds, Black Sabbath’s place in the pantheon is secure. The Summer Of Love was barely over when they midwifed the twisted offspring of the blues that would eventually be called heavy metal. They were hippies at heart, but ones who had grown up amid the impoverished streets and bombed-out houses of 1950s and 60s Aston, a world away from Haight-Ashbury and ‘be-ins’. Ozzy has pooh-poohed the idea that Sabbath were a musical incarnation of the heavy industry of post-war Birmingham, but it’s hard to imagine them coming from anywhere else. Could you see Penge or Chipping Norton throwing up a band like Black Sabbath? Exactly.

“It was just a bit of fun at first, you know,” says Geezer Butler. “Not being in a line at the dole office, just to get out of Birmingham and travel. The beginning of any band is always fun. It’s when the money starts coming in that everything changes.”

If Tony Iommi is courteous and Ozzy Osbourne hilarious, then the bassist is the personification of lugubriousness. Desert-dry, and resolutely unimpressed by everything going on around him, he’s living proof you can take the boy out of Birmingham but you can’t take Birmingham out of the boy. When he does laugh, it’s a sudden throaty cackle that goes up as a quick as a bushfire.

He admits to suffering from depression in the past, especially during Sabbath’s early days. Paranoid, a song whose genuinely tortured lyrics have been lost in familiarity, was written by Geezer about his own mental state.

“I used to be a cutter,” he says. “I’d cut my arms, stick pins through my fingers, that kind of thing. I used to get really depressed and it was the only thing that could bring me out from it. If Sabbath hadn’t made it, I’d have been long dead. I’d have killed myself.”

Sabbath may have provided salvation, but it’s still been a complicated and sometimes tortuous journey over the last 48 years. When the highs – commercial and chemical – of the seventies wore off, Geezer watched the band he’d co-founded slowly unravel. First Ozzy left, then Bill Ward followed him. Geezer himself quit in 1984, just after the ill-fated Born Again album, featuring Deep Purple singer Ian Gillan.

“I left because my second child was born and he had problems, so I wanted to stay with him,” he says. “I told Tony I couldn’t concentrate on the band anymore. But I never fell out with anybody.”

This much is true. Where bad blood soured the friendship between Ozzy and Tony, Geezer kept good relationships with both. Over the next 15 years he bounced between Ozzy’s solo band and various iterations of the Iommi-led Sabbath, some of which were more successful than others.

There had been behind-the-scenes talk of reuniting the classic line-up, most notably after the then-current version of Sabbath opened for Ozzy at two shows in California in 1992. But it would be another five years before it actually happened. The Ozzfest tour and the two Birmingham shows rejuvenated the legend, restored friendships and made a stack of money for all involved.

“It’s always a money thing,” Geezer says drily. “No, I’d just done something with Ozzy and gone back with Tony, and I said to him it would be great if Sabbath could get back together in a friendly way and finally do a tour.”

If the reunion was a ringing success, then their first attempt to record an album was less so. In 2001 they tried to make a record with producer Rick Rubin.

“It was really forced,” says Geezer. “Ozzy really wasn’t into it. We were in Wales, and he’d stay in his room most of the day, or he’d come in and sing for five minutes then go and make a cup of tea and not come back again. We came out with, like, six songs. We played them to Rick Rubin, and as we were playing them to him I realised they were no good.”

Just over a decade later, the three of them, minus Bill Ward, tried again with Rubin. This time they were more successful. The resultant album, 13, gave them their first US No.1.

Looking back, was 13 a success?

Geezer: Yeah. Especially God Is Dead. In 2001 we just went in with nothing. We were starting from scratch, we didn’t have anything to aim at. This time, Tony had this ridiculous amount of riffs – like, eighty great riffs.

Ozzy: Rick Rubin didn’t fuck around. He’d go: “No good, no good, no good, that’s good.” Which is weird for me, because in the seventies if anyone had said that we’d have gone: “Fuck you, get out.” But now you’re an older person, you’ve got to be humble. It’s as if you don’t know what the fuck you want, so you’ve got to sit there like a dummy and go: “Yes Rick, fabulous. Okay Rick, nice.” I had to divorce myself from the procedure.

Tony: Yeah, I think it was. Rick works so differently from how we would work. He wanted to recreate the old sound. But it’s hard to go back and try to do something you’d done forty-odd years ago. We went along with it. Some of these songs I’d recorded at home, and in my mind they were better sounds. When we came to record them, they were flat, the sound was a bit small. It was good that he pushed us, but the sound could have been a bit better.

Was the plan always for 13 to be the last Black Sabbath album, or did you think you’d make another one after it?

Geezer: We went in there with the sole intention of doing that one album and having something new to tour with.

Tony: After all these years, it was an achievement to make one album to be honest. We’d written sixteen songs. Sabbath had never, ever written 16 songs for an album. Sometimes, we’d barely written eight.

But after 13 there was some talk of doing another album.

Tony: As a matter of fact, yeah, I thought we may do another album, so I wrote a bit of stuff. But we never a hundred per cent decided we were going to do an album. We talked about how we’d like to do another album, and then when it came to the crunch, we had a meeting and everybody wasn’t on the same page with it.

Geezer: I was the main one that said let’s just concentrate on the doing the final tour, and if an album’s got to come out, we’ve got plenty of time after the tour to do it. I think Ozzy was a bit relieved.

Ozzy: It would take three years. I‘m fucking sixty-seven now, and I’d be seventy by the time we got to tour. I said: “If we do another album we’d be fucking dead before we had chance to tour it.”

Be honest: do you want to do another album?

Geezer: At the moment it’s just getting through this tour. The way everybody’s dropping like flies, that’s the main thing: “Please God get us through this tour.”

Ozzy: Ask me when I’m sixty-nine.

There’s a lot of heavy machinery driving Black Sabbath in 2016, though it’s tucked away behind a curtain so the world can’t see it. Each of them has their own manager (Ozzy and Geezer are managed by their respective wives), each presumably with their own schedule and own interests. This isn’t unusual for a band of Sabbath’s stature and vintage. The band themselves seem to deal with the business side of things by ignoring it as much as they can.

On the road, they don’t really socialise, though this isn’t particularly unusual either, especially when you’ve spent nearly 50 years, on and off, in each other’s pockets. “Look, Geezer’s a vegan,” says Ozzy. “He’s doesn’t want to come for a fucking Indian with me.”

But there’s an unmistakable bond between them, forged in the white heat of those early years. Sure, that bond has been strained at certain times over the years. Even as recently as 2010, Ozzy sued Tony Iommi over rights to the Sabbath name (they apparently settled out of court, but it’s still a subject neither wants to talk about). Forty years ago, at the height of the carnage, the atmosphere would have been very different. Today, with the end seemingly in sight, the vibes are that bit mellower.

“We say to each other: ‘Have a good show,’” says Ozzy. “Everybody gets on. Nobody’s going: ‘Shut the fuck up would you, you cunt,’ like we used to.”

Maybe it’s because the end is in sight. Or maybe once you strip away the booze, drugs and ego, it’s simply in their DNA. For all the fame and the success and the money and the chihuahuas, there’s still a bond between the three of them that you can trace back to their working-class upbringings. Even now, you get the feeling it could be taken away at any point. The fact it soon will be doesn’t alter that.

“This band saved me,” Ozzy says emphatically, echoing Geezer. “If I hadn’t joined Sabbath I’d have been dead. Dead or in jail. I wasn’t a baddie, I was a fucking fool. If someone went: ‘Throw a brick through that window’, I’d go [mimics the throw]. I was fucking out of control, but kind of zany with it. Even in fucking Sabbath…” He peers over the top of his shades. “Have you seen that Amy Winehouse film?”

The documentary? No. Why?

“Fucking hell, you’ve got to see it. It was so sad, man. It’s like watching a flower die. She used to hang around our house all the time. A friend of [Ozzy’s daughter] Kelly’s, like, I was that girl for fucking ever, but God must have shined on me, because I got out. I thought, ‘I ain’t doing it any more.’”

All of Sabbath have had their brushes with death. For Ozzy it was the quad bike crash and countless drug and booze binges. For Tony it was lymphoma. For Geezer it was a near-fatal car crash in the 70s, when he flipped his Jensen sports car on a country lane, and only escaped decapitation by being flung into the back seat. That they’ve all come through with their lives – and most of their sanity – intact is a minor miracle.

“We signed our life away on the first few albums,” says Geezer. “I often think about what might have happened if we’d got an accountant and lawyer and signed a proper deal. We’d all have been millionaires. It’d have gone to our heads though. We’d have all overdosed or died crashing our Ferraris,” he adds, ever the optimist.

What are you going to do after this tour finishes? Put your feet up? Do the garden? Watch daytime TV in slippers and comfy trousers?

Ozzy: Fuck off! When people stop, they fucking die. My father was offered voluntary redundancy. He said: “They’re going to give me a cheque.” I said: “Well, what are you going to do?” He said: “I’m going to take the cheque. I’ve always wanted to do the garden, so I’ll do the garden.” So he got the cheque, did the garden, then fucking died. He had nothing to get up for.

Tony: First and foremost I’ll have a break and enjoy a bit of home life, which I haven’t done for so many years. We’ve been busy. Then being ill as well, that really ruined it.

Geezer: I’d like to travel a bit more with me missus, see the world, instead of being stuck in hotels.

Are you still writing songs?

Geezer: I still write all the time. Not particularly songs, just going into the studio. It’s one of my hobbies, writing music. Not metal or anything particular. It could be, I dunno, dance stuff. The trouble is, I start something and then thirty seconds into it I get another idea. I’ve got hundreds of thirty-second songs.

Tony: Yeah. I can walk in at home, put all the gear on and just come up with ten or fifteen riffs. It’s weird, it’s probably one of the few things I can do.

So where are these songs likely to end up? On a solo album?

Geezer: [Laughing] Not if it sells like my last solo albums.

Tony: I dunno. Maybe I’ll do some TV stuff or whatever. [Laughs] Anything that’s offered.

Will you go back to your solo career, Ozzy?

Ozzy: I’ll be carrying on. The first time I retired, I thought: “Now what the fuck do I do?” I was bored within three fucking seconds. How can you retire from this? I’ll retire when I can smell pine. What else can I do? I can’t do anything else.

Ever thought about politics, Ozzy? Donald Trump has proved that people don’t care about politicians, they want characters.

Ozzy: I like watching Donald Trump. He’s amusing. But he’s fucking nuts. He’s living in a fantasy world. Can you picture him speaking at the United Nations? “We’re gonna build a fucking wall around China!” “Yeah, okay Donald. Now fuck off.”

If you’ve never been behind the scenes at a big gig by a band who have been around for the best part of 50 years then don’t worry, you’re not missing out on anything.

In the case of Black Sabbath, the backstage area consists of a long, wide corridor off which various rooms are being used for either show-related matters (catering, tour production, wardrobe) or curtained-off dressing rooms.

All three members have their own areas. Ozzy and Geezer have separate rooms, while Tony shares with keyboard player Adam ‘Son Of Rick’ Wakeman (of drummer Tommy Clufetos, there’s no sign). All of these rooms are off-limits to anyone without a Sabbath super-pass.

Alcohol and other mind-altering substances are conspicuous by their absence. “If it was fucking 1973 I’d be doing drugs, doing a line of blow or what,” says Ozzy. “But now we’re just enjoying it. I don’t know how come we took this fucking long to do it.”

There is pre-show business to attend to. Around 200 people have gathered to witness a soundcheck in the empty arena, and most will stick around for what’s billed as an Official Meet & Greet package.

The former ($419, or around £200) consists of roughly 30 minutes of banter, wisecracks and gags by a voluble crew member-cum-warm-up man named Big Dave, before Iommi and Butler turn up to play an instrumental version of Symptom Of The Universe, and, for the grand finale, they’re joined by Ozzy for Iron Man. The latter ($1,499, approximately £700) is basically a swift photo with the three band members. Tony looks welcoming, Ozzy looks enthusiastic, Geezer looks like he’d rather be somewhere else.

You can view such money-making stunts as going against the spirit of rock’n’roll at best and sheer greed at worst, but ultimately it’s a simple case of supply and demand. If people want to fork out that much money – and it’s clear they do – then it’s their call. And if this truly is Sabbath’s last lap, then they’re not going to get another chance.

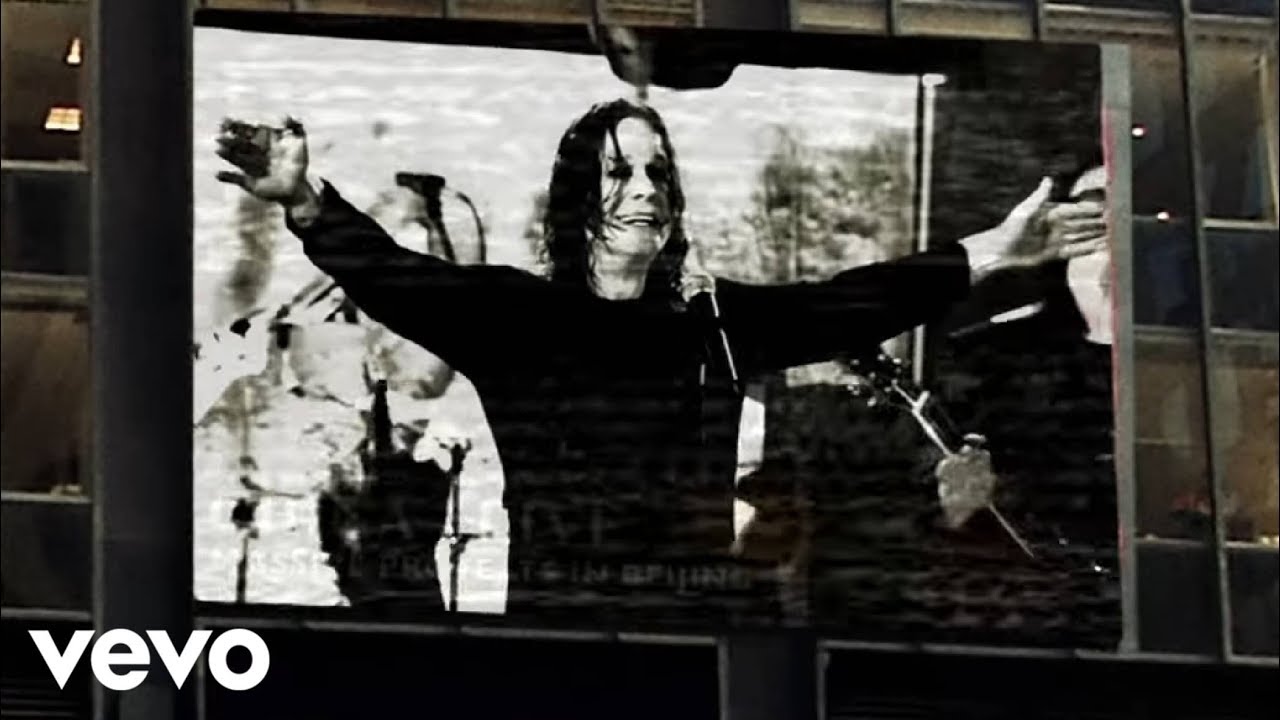

For the 12,000-odd people who haven’t chosen to rub shoulders with their heroes, the sight of Sabbath on stage for one final time is enough. It’s a route-one set, almost exclusively centred around the first four albums: Black Sabbath, War Pigs, Paranoid, the odd curveball in the shape of Behind The Wall Of Sleep. There’s nothing from 13. In fact the only song that isn’t from their first four albums is the perpetually awful Dirty Women, a song they clamped their jaws around back in 1997 and have doggedly refused to let go of ever since.

But there is something different about Sabbath this time around. Maybe it’s the new‑found energy that Geezer Butler talks about, but they’re sharper and better than they were last time around. Ozzy, especially, is clear and lucid – no buckets of water hurled around to distract from what is or isn’t happening on stage (though at one point he does hook on an ample grey bra that has been hurled up from the crowd, to Iommi’s visible hilarity). If they really are exiting stage left, they’re doing it with dignity. Grey bras aside.

This tour is scheduled to end on December 4 in Sao Paolo, Brazil. Will there be any more live shows after that?

Ozzy: Is it? I dunno. I just turn up where I’m told.

Geezer: I don’t know. The tour seems to be extending itself.

Have you thought about ending it where it began, in Birmingham?

Tony: It would be nice to finish it in our home town, but there are no plans.

Would putting fifty quid on your final show being at Aston Villa’s football ground, Villa Park, be a good idea?

Tony: [Laughing] You could. But like I say, there’s nothing been presented to us yet as far as anything like that.

Geezer: No, definitely not.

Ozzy: I would love to play the Villa Park. I would love to. But they say “play there”, I’ll play there. I don’t give a fuck as long as there’s a crowd.

Would you extend the invitation to Bill Ward to come up play a few songs at a show between now and the end of the tour?

Geezer: I’m not saying anything about Bill whatsoever, because I always get misquoted on it. That’s always what happens.

Ozzy: I’d absolutely love to. But I don’t want to go there with Bill, because he gets fucking irate and starts calling me all these names. If you want to know about Bill, ask Bill.

Is this really the end of Black Sabbath? It’s not like you haven’t retired before and then come back.

Ozzy: It is for me. I’m not gonna do it any more. I’m going to continue with my solo stuff, but Sabbath… I don’t know if they’ve got a fucking guy waiting in the wings. If they want to get another singer, fine. They’ve had more singers than a fucking choir.

Can you see yourself doing anything in the future with the other two, either separately or together, that isn’t Sabbath?

Ozzy: Anything’s possible. The thing with Sabbath is we’re definitely not going to tour like this any more. We just won’t. But I don’t know what’s going to come down the pipeline.

Geezer: I’d love to. I’d love to still work with Tony and I’d love to still work with Ozzy. But a Sabbath thing? No. Unless somebody offered us a hundred million dollars to do their birthday party or something.

So can you confirm, for the record, that there will one hundred per cent not be another Black Sabbath album or another tour?

Tony: No. I can’t confirm anything, because I don’t know what’s going to happen. We’ve certainly not spoken about anything apart from this being the last tour. And it’s definitely going to be the last tour.

Geezer: I can never say never with this band. Back in 19-whatever-it-was, I said that there was never going to be another Sabbath tour. Look how that turned out.

Ozzy: For me, no, there won’t be. But then it’s a difficult question, cos if my wife goes: “Get your fucking arse in the studio with them,” then that would be a yes.

Ever the hippie, Geezer Butler has been reading up on morphic resonance recently. “Morphic resonance means that things that happened in the past will happen again,” he says. “Or you could be a million miles away from each other and you’ll be thinking the same thoughts. That’s us. We all seem to think the same thing at the time. That’s the way we got together in the first place.”

Morphic resonance might be pushing it, but the fact stands: in six months’ time, Black Sabbath won’t exist, except as an echo from the past. Sure, we’ve been here before, two or three or four times, depending on how you measure these things. But this time it really does feel like the end. No, it’s not like Lemmy or Bowie or Prince dying, but ‘Black Sabbath RIP’ still has a tinge of sadness to it.

“The thing is,” says Ozzy, “Sabbath is the best thing that ever happened to me in my life. I’ve been solo longer than I was with Sabbath, but if it wasn’t for Sabbath I wouldn’t be here now. But everything has to come to an end, and this is the end. Honestly.”

There’s a pause for maximum comic timing. “Anyway, I’d look a right fucking turd if we ever did come back.”

Originally published in Classic Rock 224, May 2016

Dave Everley has been writing about and occasionally humming along to music since the early 90s. During that time, he has been Deputy Editor on Kerrang! and Classic Rock, Associate Editor on Q magazine and staff writer/tea boy on Raw, not necessarily in that order. He has written for Metal Hammer, Louder, Prog, the Observer, Select, Mojo, the Evening Standard and the totally legendary Ultrakill. He is still waiting for Billy Gibbons to send him a bottle of hot sauce he was promised several years ago.