March 17, 1973. Black Sabbath play The Rainbow Theatre in London’s Finsbury Park. It’s the twenty-fourth of 25 shows across Britain and Europe that they have completed in a 32-day period. Everyone is exhausted, propped up on speed, coke, dope, acid – anything they can get their hands on to keep going. It’s the band’s second of two shows at The Rainbow, their last night in London, and there will be a big party afterwards. The following day they will lie comatose, flopped across the tiny seats of a small propeller plane as it bundles them north to Newcastle for the tour’s final show, at the City Hall.

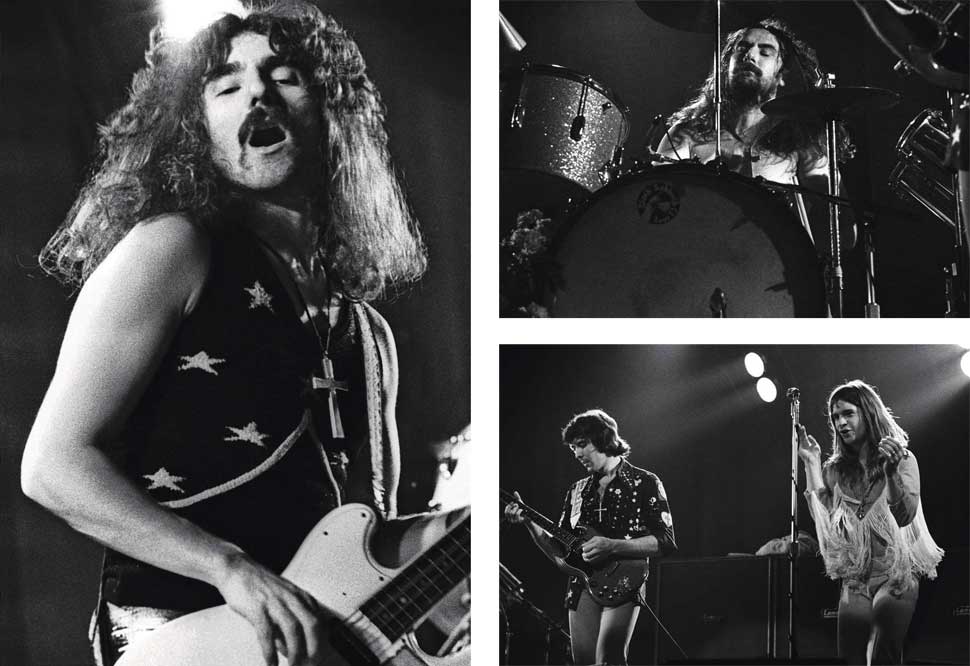

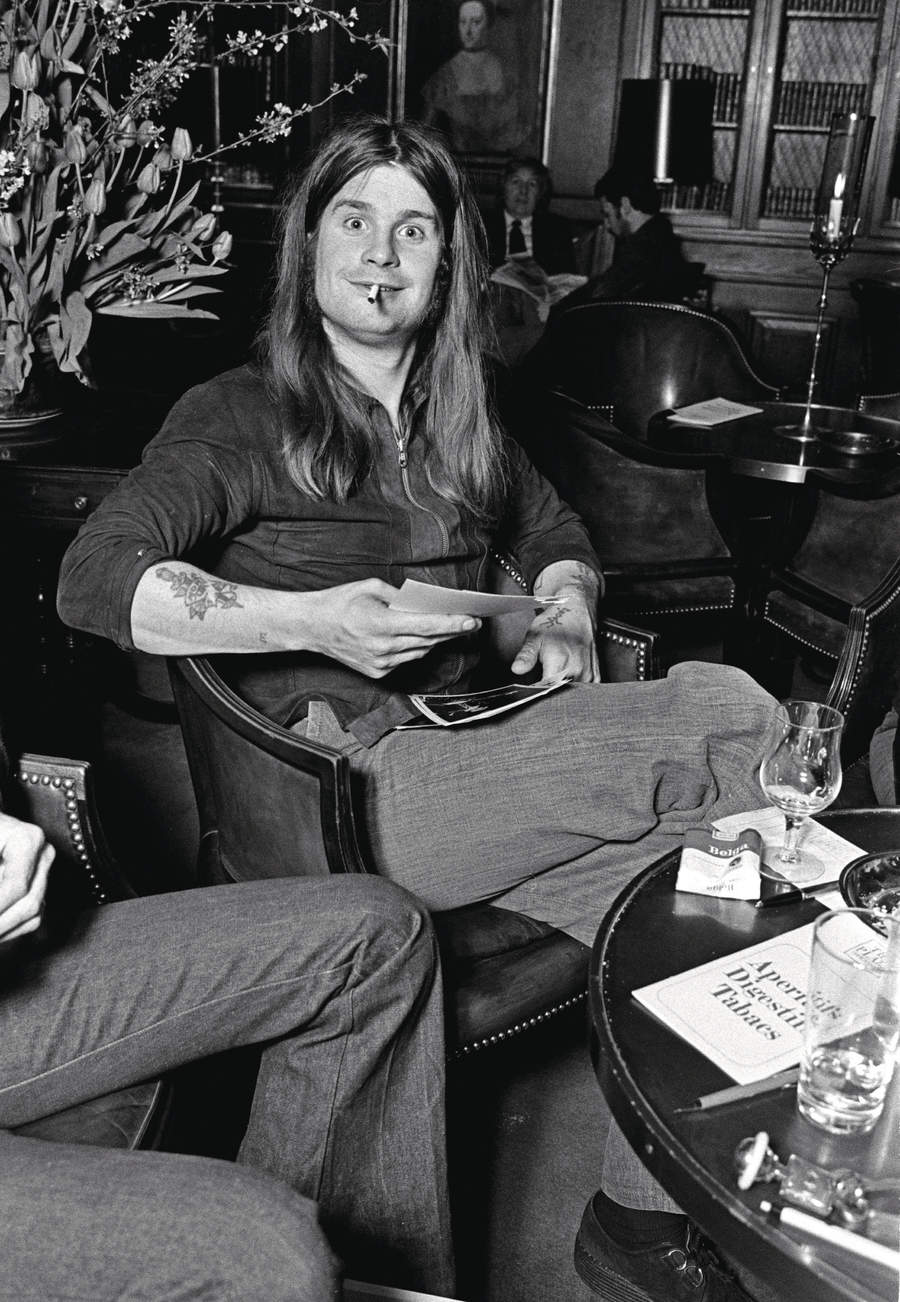

Right now, though, Ozzy Osbourne, Sabbath’s 24-year-old officially ‘loony’ singer, knows only the Rainbow spotlight and what it’s doing to his head. Grabbing onto the mic stand with both hands, to stop himself from falling, he yells into the darkness: “Are you high?”

The audience, almost exclusively male, greatcoated and long-haired, respond with a muted: “Yeaahhh…”

Ozzy tries again. “I said are you high?”

Same response, only a little louder this time.

Ozzy stares at them forlornly. “Are you high?!” he screams at the top of his voice.

This time the place erupts.

“Good!” he tells them. “Cos so am I!”

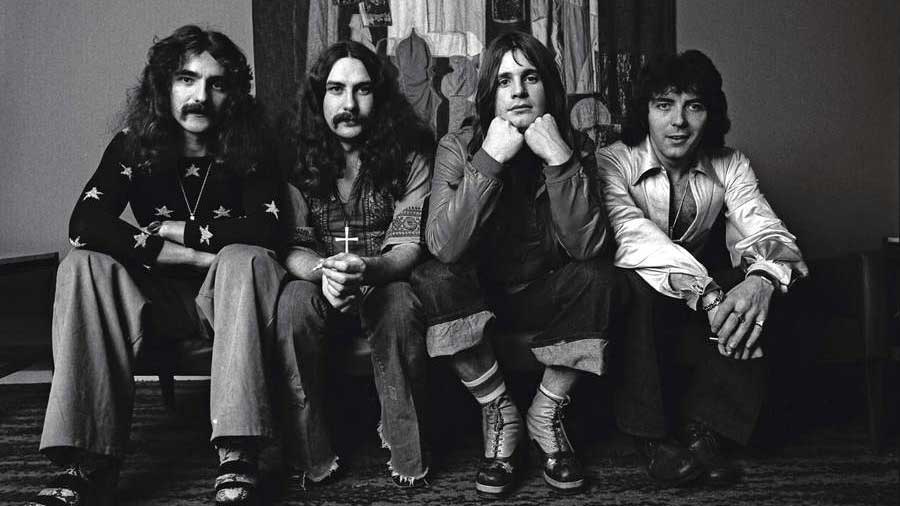

Tony Iommi swipes at his guitar, and the ugly, tormented riff to Snowblind detonates, bassist Geezer Butler and drummer and Bill Ward thrumming as the building shudders. This is what it’s all about in 1973, man. Not all that glam stuff you see on TV, but the fully loaded realisation of what rock music has become: hard, vicious, undeniable. And completely critic-proof.

What no one knows is that a few days after the Rainbow show there’ll be a phone call that quietly cancels what should have been Sabbath’s next US tour. Promoters will be furious. But eight months on the road has nearly killed them.

Now all Iommi wants is to get back into the studio and produce the masterpiece that will, finally, he is determined, prove that Black Sabbath are as important, as worthy of serious consideration, as the bands they have been outselling, like the Rolling Stones and Deep Purple; like anyone you would care to name, with the sole exception of Led Zeppelin, who are now outselling everybody.

The other members of Sabbath want it too, but not nearly as much as Iommi does. The others still feel more comfortable sitting at the back of the class, sneering at teacher. Not Iommi. He wants Sabbath to carve out their own hallowed place in the pantheon, and for the name Tony Iommi to be up there, where he feels it belongs, alongside those of Jimmy Page and Ritchie Blackmore, Jeff Beck and Eric Clapton.

As he complained in an NME interview that year: “On drawing power and album sales we can compare with groups like Zeppelin and The Who, although we seldom get recognition for the fact.” He wasn’t just a heavy rock guitarist, he complained. “I’ve got a few tapes of Deep Purple in the car, but I prefer to listen to things like Peter Paul And Mary, Sinatra, the Moody Blues and The Carpenters.”

He was an artist. People didn’t understand. “I want to move to a bigger house,” he said. To get away from everybody so he could work undisturbed, the Phantom Of The Rock Opera.

“I have a big house with a swimming pool now, but I want one with tennis courts and a studio, so I have everything in the house and don’t have to go out at all…”

Iommi had recently fallen for Susan Snowdon, a “posh bird” introduced to him by Sabbath’s manager. Snowdon said she was a singer; Iommi offered to write for her. However, as he recounted in his 2011 memoir Iron Man: “She came up to my house one day and it was a bit awkward. I found out she couldn’t sing – and she found out I hadn’t written a song for her. But we did go out to dinner, and that’s how it all started.”

They were worlds apart, opposites that attracted. But it was clear from the day they got married in November 1973 that they were destined to remain strangers throughout the seven years they would be together.

Susan’s wealthy father invited the newlyweds to move into his 200-room mansion on several hundred acres of grounds halfway between Birmingham and London. Iommi finally had his house with ‘everything’ and didn’t have to go out again – ever.

Between tours, while the rest of the band took their wives and girlfriends on long holidays, Iommi stayed behind to work alone in his new home studio, snorting coke and ‘creating’ long into the night.

Iommi craved the one thing money couldn’t buy: respect. Sabbath had been going to release a double live album, à la Deep Purple, whose double live Made In Japan, released in December ’72, was now a colossal international hit. Plus a live album cost relatively nothing to make, an idea that particularly excited everyone.

But when Iommi listened back to the tapes, he was aghast. This was primeval Sabbath, heavy as hobnailed boots trudging through mud, obnoxiously loud and overbearing. Exciting for the audiences that were there for the shows, perhaps, but utterly enervating on record, as draining as a coke comedown. And as a signifier of where Iommi wanted Sabbath to go, completely off-message. He binned the idea.

And so it was that in the summer of 1973 Sabbath found themselves back in Los Angeles, working on their fifth album. Because it was just easier, they retreated to the same Bel Air mansion where they’d conceived their previous album, Vol.4, and immediately called the same drug dealers and groupies that had made their time there the year before so ‘inspiring’.

But while the rest of the band thought they were making what would effectively be Vol. 5, Iommi had bigger ideas. Unlike previous Sabbath albums, most of which had been recorded on the run, between tours, this time things would be markedly different, he decided.

Instead of simply conjuring a mood and going with it as they might a live jam, they would step back and take time to consider what they had and how they could improve it, and worry later about how they would or wouldn’t be able to reproduce the new material live. Build something up-to-the-minute that the fans and the critics could begin a whole new conversation about; alter perceptions so that Black Sabbath no longer laboured under the imprimatur of a loud, clanking heavy rock band, but were something more exhilarating and nimbler on its feet.

Something where the music really did come first, where it could be allowed to rehabilitate itself into something more in line with new headline makers like Yes, whose daring 1973 double album Tales From Topographic Oceans would ostensibly have just one track per side of vinyl, and Pink Floyd, who with the release that same year of The Dark Side Of The Moon had left behind their earlier image as psychedelic prophets to metamorphose into progressive rock goliaths. Concept albums were now de rigeur for the rock artist looking to be taken seriously. Iommi listened to The Who’s 1973 double album Quadrophenia, read the liquorice reviews, and felt that Sabbath were being left to die by the side of the road.

There were also commercial pressures to consider. For all their understandable satisfaction with the way Vol. 4 turned out – the first Sabbath album not to be made under the gun of budgetary restrictions – it had essentially been more of the same, but with a more polished production sheen. And although it had gone gold in America, Vol. 4 had reached only No.13 in the chart, lower than either Paranoid or Master Of Reality. It was the same story at home in Britain, where it stalled at No.8.

Suddenly, Sabbath’s previously skyward sales trajectory had tapered off. They still sold tickets for shows, but their fan base had given a clear indication that it already had enough Sabbath albums to be going on with and maybe didn’t need any more. The perception was that unlike The Who or Led Zeppelin, Black Sabbath had stood still musically. With their heads buried in booze and coke, Ozzy, Geezer Butler and Bill Ward might not have noticed it, but in the summer of 1973, as Iommi struggled to come up with what he knew had to be genuinely new and startling music, he was painfully aware that it was now or never for Black Sabbath.

Buoyed by the full repertoire of rock’n’roll remedies, Iommi immersed himself in non-stop 36-hour shifts at the Record Plant. As he told me: “It became a ritual. Every time we’d do an album, we’d get a load of dope and then some coke, and off we’d go. We’d be there all bloody night writing stuff, and I never used to want to leave the studio.”

This time, though, the old tricks simply weren’t working.

“We thought we’d go back to LA,” he said. “Do everything the same – the house, studio… everything exactly the same. But nothing happened. We just dried up. It all just fell to pieces for us.”

He began to get furious with the others, then desperate with himself. One day, he walked into a hairdresser on Hollywood Boulevard and ordered them to cut his hair – short. When he got back to the Bel Air mansion, he also shaved off his moustache. Iommi became unrecognisable to his own band – even to himself. Yet still things would not fall into the place in the studio.

Finally, in June, he threw in the towel and ordered the band back to England – in order to try to re-establish some sense of normality – before starting again.

Ironically, the place Sabbath chose to regroup was even weirder than the demented atmosphere they had fled from in LA. Clearwell Castle, an 18th-century neo-Gothic pile in the Forest of Dean in Gloucestershire, had been built for the Member of Parliament Thomas Wyndham in 1728 to replace an older house that had occupied the same site. Constructed of local stone with battlements, and an ornate gateway formed by two huge towers, it had been restored to former glories in the 1950s by the son of the former estate under-gardener, Frank Yeates.

When Yeates died in 1973, he left behind within the castle a newly built rehearsal room and basement recording studio. Having noted the burgeoning number of large countryside properties now being occupied – at no little cost – by the new generation of album-oriented rock sophisticates, Yeates had shrewdly decided to get in on the act, and for the rest of the decade the dark, atmospheric basement of Clearwell Castle would be temporary home for a number of highprofile rock acts recording there, including Mott The Hoople, Bad Company, Deep Purple and Led Zeppelin.

The first band to rent and move into the property for such purposes – somewhat fittingly, given the subterranean aspect of the facilities – was Black Sabbath.

What they did not discover until they were actually sleeping there was that the castle was reputedly haunted by a mischievous female ghost whose modus operandi was apparently entering locked rooms and leaving them in a mess, as though a strong wind had blown in through the windows. She was also said to sing lullabies to her ghost child on the landing at night while playing a tinkling musical box. The band were not told any of this, lest it should freak them out. But they certainly felt the vibes.

The first few days they were there, rehearsing new material in the former dungeons, they all saw a shadowy figure in a long black cloak hurry past the door. Wary from so many previous experiences of black-robed Sabbath fans making their unwelcome presence felt, Iommi stopped playing and, with a roadie, ran after the rapidly retreating figure.

“They saw him go into this other door at the end of the corridor,” Butler recalled. “They were shouting at him, because they thought he was some lunatic that got into the castle. They went into the room where he had gone into and there was nobody in there.”

When they asked if any other visitors were staying at the castle, the owner told them: “Oh, that’s just a ghost.” The castle was full of ghosts, he shrugged. The band stood and stared. Everyone was doing so much coke, it felt like they already had a million ghosts inside their heads. Iommi had lately become more and more convinced of his own growing occult powers.

“The whole group communicates on a very close level,” he informed one interviewer solemnly. “Like, we have what you could almost call a third eye. We can sense with each other what is going to happen. We’ve had actual experiences. One I remember, Geezer was asleep, and he must have astral travelled. I was stuck in the lift. He dreamt this. When I woke him up, he said: ‘I’m glad it’s you, cos I just dreamt you were stuck in the lift.’ These are quite regular occurrences. They used to frighten me at first, till I got used to it.”

Continually coked up, strung out on paranoia and bad dreams about ghosts and castles, assaulted by Iommi’s manic perfectionism, resulted in hours of lost time. “We’d spend all day farting about and end up with nothing usable,” Iommi glowered.

In desperation to meet Iommi’s demands for something – anything – new to add to the Sabbath gene pool, the band tried everything to find different sounds and textures. And, gradually, things did begin to happen.

“We’d end up coming up with all these brilliant ideas,” said Iommi. “Like trying things going off the piano, into the piano and then mic-ing up the piano strings to hear different sounds.”

At one point, Bill Ward took an anvil he’d found while poking around the castle’s outhouses and recorded himself dropping it into a barrel of water. Iommi brought in unusual instruments that he felt went well with the castle’s permanentmidnight ambience: river-deep guitars, old-school orchestration (name-checked almost apologetically on the album sleeve as The Phantom Fiddlers), even bagpipes for what would become the album’s big sign-off epic, its very own Stairway To Heaven grand finale, the monumental Spiral Architect. Butler’s final message was reassuringly universal: ‘I look upon my earth and feel the warmth and know that it’s good…’ The tacked-on sound of applause at the end added an extra level of funhouse grandiosity.

For all the intensity, there would be a lightness of touch to the new material too. With Iommi in full control of proceedings now, the Sabbath sound became less about thuggish riffing and brutal rhythms, and far more about a newly mellifluent style that could embroider even woolly-mammoth riffs like Sabbath Bloody Sabbath, the heavyweight title track, its unexpected sideways contortions, jazz-like, awash with zinging electric and acoustic guitars and Butler’s pulsing new fuzz bass: an instant classic to go with War Pigs and Iron Man.

Next track, A National Acrobat, twists the sound into more recognisably malevolent Sabbath territory, yet even then the shift is all space and time, with Iommi leading the band into a whole new sonic galaxy.

The band were also having greater fun with lyrics. Ozzy singing ‘When worlds collide, I’m trapped inside, my embryonic cell’ might sound like it’s from Butler’s HG Wells-obsessed vocabulary, but in fact, he told me, A National Acrobat “is about wanking. Not that anybody got it.” That is, a song about wanking “told from the sperms’ point of view”.

The only droopy moment was the now seemingly obligatory acoustic instrumental, titled Fluff – named after Alan ‘Fluff’ Freeman, Radio 1’s voice of rock in the 70s, whose Saturday afternoon show was famous for the listeners’ letters that always seemed to begin: “Dear Fluff, more Sabbs, more ELP…”

The novelty of such interludes had long-since worn off. Iommi was insistent, however, that the band continue with them, as part of his attempt to demonstrate how much more there was to Sabbath than blunt-force trauma-metal.

The rest of the new material, though, found Sabbath touching new heights: Sabbra Cadabra was pure, bounding rock’n’roll, its ‘Lovely lady make love all night long’ lyrics made-up on the spot by Ozzy, based on the preposterous voice-overs on some of the German porn films he’d been watching. Butler cohered them into lyrics, and Yes keyboard player Rick Wakeman was brought in to add some honky-tonk piano and cathedral-like synthesiser. The vocals and guitar were run through a processor that gave them a futuristic sheen.

Wakeman, said Iommi, “was wild back then”. Certainly too wild for Yes, who had opened for Sabbath in the US some years before.

“Rick used to travel with us, and not Yes, for some reason,” Iommi said with a chuckle. When the beer-and-curry quaffing Wakeman left the brown rice-eating Yes later the same year, there was some discussion about bringing him into the Sabbath fold full time. But Wakeman had had enough of the band-on-the-run lifestyle. When months later he had the first of what would eventually be three heart attacks, his decision not to join Sabbath just as they were reaching the low-water mark of their own ‘personal issues’ seemed prudent.

The four tracks on side two of Sabbath Bloody Sabbath were similarly inspired, similarly lyrically playful, similarly unhinged. On Killing Yourself To Live they gave a glimpse into the fear and loathing behind the scenes, its crunching bass and grooveladen drums over a bed of synthesised vocals and guitar lending it an air of authentic melodrama, Ozzy issuing his entreaty over the lost-in-space bridge: ‘Smoke it… Get high!’

It’s the same feeling on Looking For Today, with the days of meat-hook riffs firmly in the past as the band build on a galloping new buzz that is so streamlined and catchy it could have come from David Bowie’s Ziggy Stardust album. The classic Sabbath air of cobwebbed mystery had not been lost, just refurbished for the mid-70s. On Who Are You the piercing synthesisers summon an atmosphere of insomniacal mania as Ozzy pleads: ‘Please I beg you tell me, in the name of hell, who are you?’ before the ascending Bolero piano brings the whole deranged monstrosity full-circle.

As Butler said: “It was a whole new era for us. We felt really open on that album. It was a great atmosphere, good time, great coke!” It was, he said more seriously, “like Part Two of your life… Right before that we were in a terrible slump. We were all exhausted from touring. We weren’t getting on very well. Then Tony came up with the riff for Sabbath Bloody Sabbath and everybody sparked to life.”

It looked like a new dawn. But it was all an illusion. As Ozzy later said: “Sabbath Bloody Sabbath was our final record. Then it started to drift around all over the place. See, our idea of making a good record was to run and find some new location. We thought, if you travel somewhere new, it’s kind of like a new adventure. So you’d get there and for the first few days you’d jam about a bit, and then you’d be back to your old ways. You’d be locked in your own heads. Someone would come in with another ounce of fucking powder and you’d be up there talking bullshit for three weeks, you know?”

The distress signals were already flashing red by the time Sabbath Bloody Sabbath was released in Britain on December 3, 1973. It became Sabbath’s biggest-charting album since Paranoid three years before, eventually plateauing at No.4. In the US, where it was released a month later, it also reversed the downward chart trend, and reached No.11.

What it didn’t do, for Tony Iommi, anyway, was quash the doubters and naysayers that still wanted to make it their mission to trounce everything Sabbath did. Iommi was delighted, however, to finally read something good about one of their albums in Rolling Stone.

In his review of Sabbath Bloody Sabbath, Gordon Fletcher wrote in that magazine: “Black Sabbath’s major contribution has been to successfully capture the gist of specifically seventies culture through their music. They relate to this impersonal, mechanical decade much as Delta bluesmen and their Chicago spin-offs related to their eras – by synthesizing collective feelings and giving their contemporaries hope by revealing the disaffection that unites all of them. In that remote but real sense, Black Sabbath might well be considered true Seventies bluesmen.”

Well that was a load of pretentious old bollocks, of course. They knew that. But Black Sabbath were at least getting the kind of heavyweight critical respect Tony Iommi felt was their due, their right, the guitarist locked away in his hotel suite, working his way through another ounce of coke, bloodthirsting for revenge.

It was the end of the beginning.