It took a day to record. The producer on this project was making his debut in such a role. The studio was a four-track. And the whole thing cost less than one VIP ticket for a Bon Jovi show. Yet, in 1970, this unprepossessing and rather low-key debut album altered the world as we knew it. For we’re talking here of the self-titled debut album from Black Sabbath. This was where heavy metal breathed for the first time, staring down the burning sun of commercial realism and blinding succeeding generations with an uncompromising darkness of thought, deed and riff.

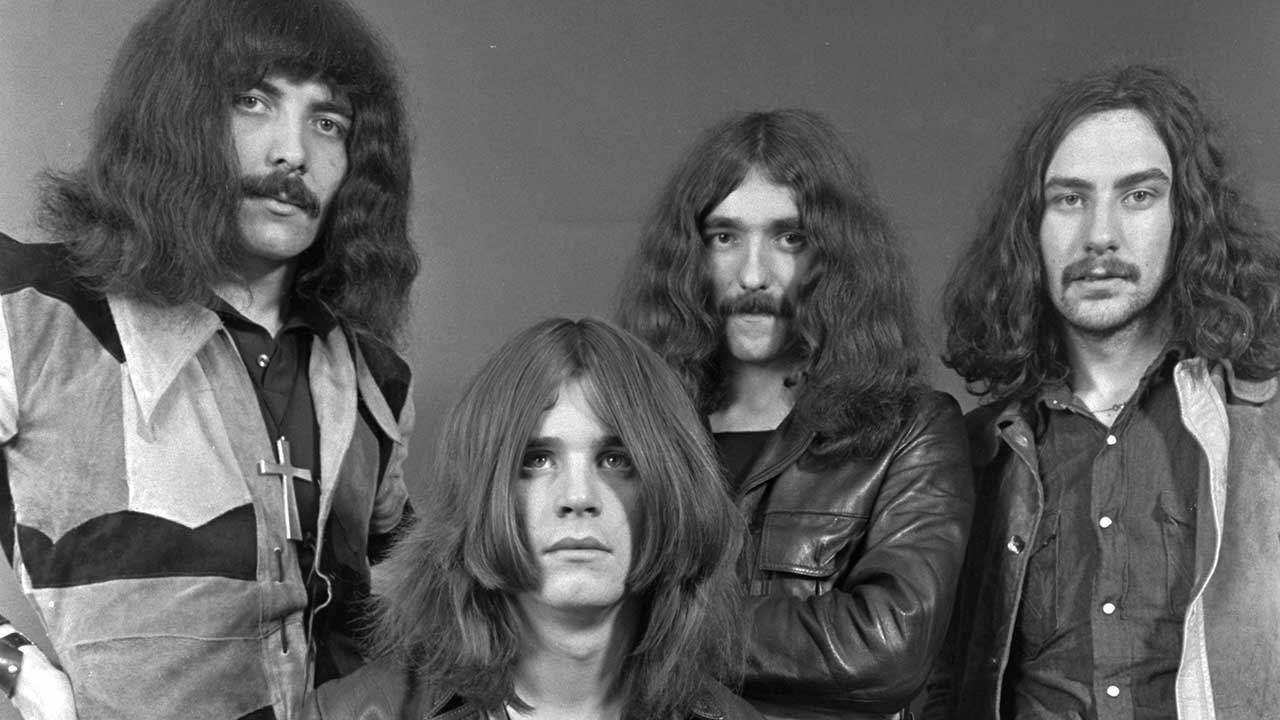

“We were different to anything around at the time,” says guitarist Tony Iommi 40 years after its release.“While everyone else was still wrapped up in the hippy and psychedelic ideas of the 1960s, this was something new.”

“We were four local lads. I went to school with Tony. I was in a band with Geezer Butler,” adds Ozzy Osbourne. “When we started, we had everything to gain and nothing to lose. It was my way out of working in a factory for the rest of my life.”

There had been indications of a coming force on the music scene before. The riff to The Kinks’ 1964 hit single You Really Got Me, for instance. The 1968 debut album from Blue Cheer, Vincebus Eruptum, and the Iron Butterfly record In-A-Gadda-Da-Vida the same year. A fascination with magick and the supernatural had imbued Led Zeppelin’s work, and could even be traced back to the blues. But nobody had ever brought it all together in such a fashion. No one had dared to attempt something so distorted, original and just musically so morose. Black Sabbath gave birth here to the beast, and we all embraced a new, gloomy vision.

“What set us apart from everyone else were our lyrics,” explains drummer Bill Ward. “There were a lot of great bands at the time – Zeppelin, Deep Purple, for instance – but none had those morbid lyrics like us. It’s what defined the band, made us unique.”

Sabbath had started out under the name of the Polka Tulk Blues Company in 1968. It was the combination of refugees from a Carlisle band called Mythology (Tony, Bill) and Rare Breed (vocalist Ozzy Osbourne and bassist Geezer). Located in the Aston area of Birmingham and augmented by slide guitarist Jimmy Phillips and saxophonist Alan Clarke, they were a heavy blues band, who quickly became Polka Tulk, and then Earth. By which point Jimmy Phillips and Alan Clarke had gone.

“In those days, Birmingham was a real hothouse for blues bands,” explains Butler. “There were loads of places to get gigs. But just about the only rock venue was Henry’s Blues House, above a pub in the middle of Birmingham. Everyone played there.”

This was run by Jim Simpson, who was to become the band’s manager and who, in 1969, packed them off to play regularly in Germany, especially at the Star Club in Hamburg, made famous earlier in the decade by The Beatles.

“We’d play up to nine sets a day,” laughs Butler. “They were all about 45 minutes long, and as we didn’t have many songs we learnt to do extended versions, to introduce drum and guitar solos. That’s how we started to jam a lot, and from where a lot of the material on the first album was developed.”

By this time, the band survived the temporary loss of Iommi, recruited by emerging prog heroes Jethro Tull. He lasted long enough to do one TV show, the Rolling Stones’ Rock And Roll Circus, before deciding their approach wasn’t for him, and returned to Earth.

The problem was that, while the band were building a healthy following on the live circuit, they weren’t at all attractive to record companies.

“We were turned down by several at the time,” says Iommi. “I think they felt we were too way out for them. Jim Simpson then decided that our songs weren’t commercial enough, and what was needed was an outside writer.”

So enter one Normal Haines. He’d made his name with another Birmingham band called Locomotive, who released a progressive-style album in 1969 entitled We Are Everything You See (now something of a collector’s item). They’d also had a hit single with Rudi’s In Love. However, the band had split up by the time Jim Simpson asked keyboardist Norman Haines if he’d be interested in joining Earth, thereby giving them some commercial beef. The offer was rejected, but instead Norman wrote the band a song called The Rebel.

Before their next move could be made, the band had to change their name. Another British act called Earth, who played pop and Motown covers, were playing the C-list circuit and this forced our heroes into a rethink. Yet they had this song, you see, and, well… it was going to become the band’s own defining moment.

“The song came first,” says Ward. “It was doomy, dark and very influenced by the supernatural. But what it didn’t have was a title. So, one day Geezer suggested we call it Black Sabbath, after a horror movie of the time [a 1963 film, starring Boris Karloff].”

Not only did this solve the problem of what to title the tune, but it became the band’s name, when forced to abandon their Earth connection. And on August 22, 1969, the newly anointed Black Sabbath went into Trident Studios in London’s Soho area to record a demo of The Rebel, with Norman Haines himself sitting in on piano and organ. The session was produced by Gus Dudgeon and engineered by Rodger Bain. In all, an amazing 19 takes were done of this song.

“Gus Dudgeon tried to tell us what to do,” says Ozzy. “And, if you knew us back then you’d understand that when we got ordered to do something a certain way, then we’d deliberately fuck it up. Gus was lucky that Tony didn’t wrap his guitar round his head!”

The ploy of using an outside writer didn’t work. The band also recorded another Normal Haines song, When I Come Down (sometimes called When I Came Down), but Jim Simpson couldn’t get Sabbath signed, which didn’t surprise Ward.

“They didn’t work because it wasn’t us. We felt uncomfortable and it shows through on the demos. We were far happier with our own material, which was very different to these songs.”

In a final act of desperation, and inspiration, Jim Simpson elected to make a bold move. He did a deal with one-time producer and jazz critic Tony Hall, who’d co-hosted a short-lived late-1950s music TV series called Oh Boy! - almost a precursor to Top Of The Pops. It was agreed that Hall would put up the money for Sabbath to do an album, and then try to sell the results to a record company.

“I think Tony Hall gave us £1,000,” says Butler. “We each got £100 to pay off debts, and the rest went to pay for the album - £600. It sounds like nothing these days!”

“I thought I was rich,” adds Ozzy. “I spent some of the money on a pair of shoes. I used to go around barefoot at the time, because I literally couldn’t afford shoes.”

On November 10, 1969, the band went back to Trident to have another go at recording a commercial cover. The song chosen this time was Evil Woman (Don’t You Play Your Games With Me).

“This had been a hit in America for a band called Crow [it reached no.19],” says Ward of the choice. “To be brutal, none of us liked the song and we didn’t wanna do it. But what did we know? Jim Simpson and Tony Hall felt it could do us some good, so we reluctantly went along with it.”

In those days, a lot of British acts were cajoled into covering recent American hits, getting their versions out before the original in the UK. And this was to be the one track on the Black Sabbath album recorded separately to the bulk of the songs. It was done back at Trident Studios, with Barry Sheffield (who co-owned the studio) as engineer and Rodger Bain as the producer.

“I don’t think Gus Dudgeon enjoyed working with us on The Rebel,” laughs Iommi. “He didn’t seem to get what we were about, and apparently turned down the offer of working with us again.”

“My recollection is that we didn’t get on with Gus at all; he was always so critical of what we were doing,” adds Butler. “We didn’t want him to do anything more for us. I know we met a couple of potential producers, but we liked Rodger Bain, because he had the right attitude. He wanted to record us live in the studio, to do it as if it were a gig. That’s the way we wanted to work, as we had no clue about studio technology.”

So, on November 17, 1969, the band went to Regent Sound Studios in London - and they literally had one day to do it all!

“Well, there was one day set aside to mix it, but we had to get all our parts done on that first day,” sighs Iommi. “It was the way things were done in those days. We had no choice. All we could was set up in this small room, and play the songs through. Mind you, it played to our strengths, because by then we were a really good live band.

“We had to be really careful to make sure there were no mistakes, otherwise they might end up staying on the record. As I recall, we did have the luxury of doing one or two songs for a second time. But that was it.”

“Tony did get to do a couple of overdubs on guitar, but when we asked all we got from Rodger and Tom [Allom, engineer] were sighs of frustration,” smiles Butler at the recollection. “Time was so tight. Then when Ozzy asked if he could do a few additional vocals, he was told, ‘No, sorry, time’s up. Now just fuck off!’.”

And that was the end of the band’s involvement with the album. The next day they left on a ferry, to play shows in Switzerland, while Rodger Bain and Tom Allom mixed the tracks.

“To be honest, I doubt we’d have had anything useful to contribute at that stage,” admits Iommi. “What did we know about mixing? All we’d have done is sit there and annoy everyone by asking for the thing to be turned up!”

“What you hear on the song Black Sabbath - the bell and all those effects - had nothing to do with us,” reveals Ozzy. “They were added after we’d left for the ferry. The first time any of us heard the mix was when we got to play the finished album.”

Not only were Sabbath absent for the mix, but they had nothing whatsoever to do with the sequencing of the tracks on the final record.

“That was done by the label,” remarks Butler. “If it had been left to us, then the chances are that we’d have opened up with something like Warning. Maybe it’s better we weren’t asked!”

The aforementioned song was a cover of a track first recorded a couple of years earlier by a British band called the Aynsley Dunbar Retaliation, and it’s something the bassist had brought to the band.

“It was a great blues song to jam on. I’d first done it when I was in Rare Breed, and really that’s where we developed the ideas which eventually came together on NIB.”

It is astonishing to realise just how little Black Sabbath had to do with their own debut album. But Iommi shrugs off the situation with a philosophical attitude.

“We didn’t know any better back then - it was the way things were done. The labels had so much control. Our part was to record the songs, and then leave the rest to them.”

“We had no experience of anything except playing live,” says Ozzy. “Jim Simpson just said to us, ‘On your way to catching the ferry over to Switzerland, stop off at Regent Sound and record your album.’ It was almost an afterthought.”

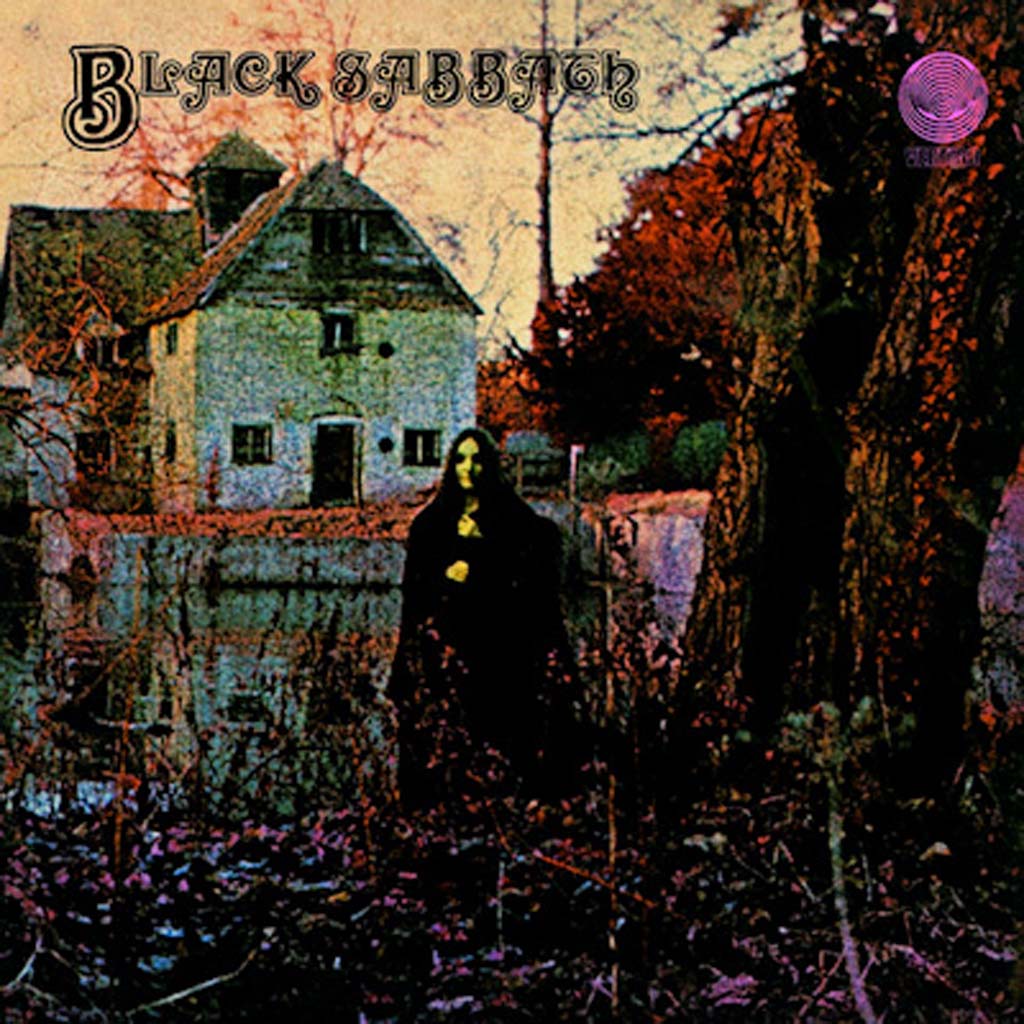

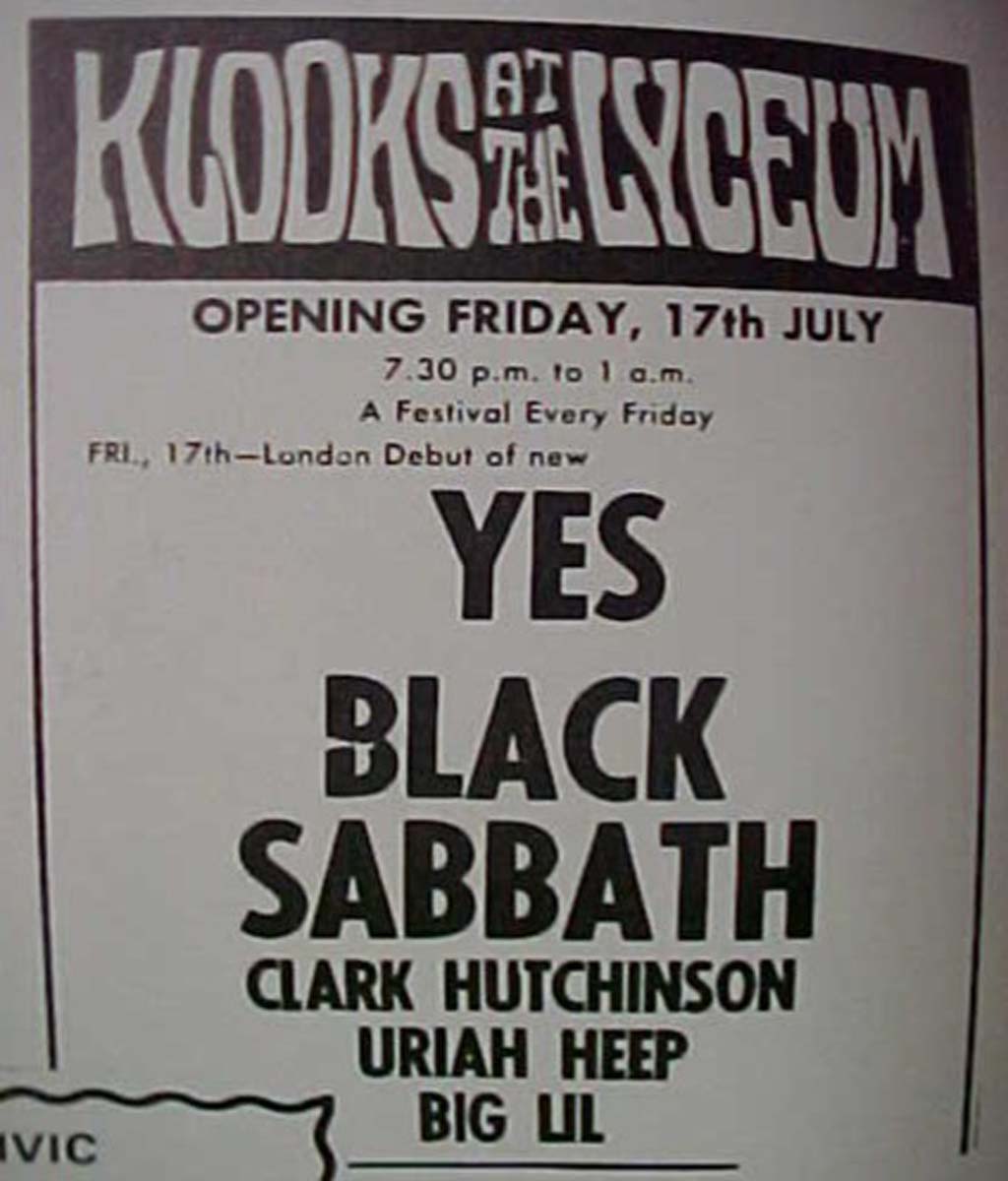

Armed with the tapes, Tony Hall managed to persuade Phillips to sign up the band, releasing Evil Woman… as a single on January 9, 1970, through their Fontana subsidiary. It didn’t chart, and it was another Phillips label, the newly formed Vertigo, that put out the album in the UK, on February 13, 1970 - appropriately enough a Friday. And this time, things happened fast, with the record reaching no.8 in the charts, much to everyone’s surprise.

“We didn’t even hear or see the album before it was released,” admits Tony. “The first we knew was when we got back from Europe, switched on the radio and heard Evil Woman… It was us. On the radio. That was exciting. But we were never sent the mixes of the tracks, nor shown the artwork. Nothing. Mind you, it was a lot harder back then to get anything to a band on the road.”

“I remember Jim Simpson telling me that the album had made the charts. I didn’t fucking believe it,” laughs Ozzy. “I hadn’t even played the record at that point, and I had no idea what it sounded like. So, I took a copy home to my mum and dad’s place, and put it on their record player. I recall my dad listening to it and saying to me, ‘Are you sure all you’re having is the occasional drink?’ That was hilarious! I was off my face all the fucking time. I must have overdosed every day back then.”

The man who signed Sabbath to Vertigo was label boss Olaf Wyper, who’d actually seen Sabbath once… by accident.

“I’d gone up to Birmingham for a meeting but got the wrong day. At a loose end, I went to a local club just to pass the time. The place was packed and there was this incredible band playing… Black Sabbath. Right then I knew I wanted them.”

In America, the album was released on June 30, and got to No.23 on the charts. Much to everyone’s amazement. One slight change was that Evil Woman… was dropped, in favour of another original, Wicked World, which had been the B-side of that first British single.

“It was actually the first song we’d wrote after we changed the band name to Black Sabbath,” says Ward. “Tony Iommi had this riff he’d come up with when we were still in Mythology.”

The centrepiece of the album was the title track - a formidable epic that builds to a deafeningly dark crescendo. As the drummer says, it’s the band’s anthem.

- How Paranoid Made Black Sabbath Heavy Metal Superstars

- The World's Funkiest Black Sabbath Tribute Band Are Back

- The 10 best Black Sabbath songs from their final tour, by Adam Wakeman

- Watch Black Sabbath take their final bow

“If you listen to that song, then for me it represents everything about heavy metal,” insists Geezer. “It’s all there - the whole genre in one song. I got the idea from an incident when I woke up one night and there was a mysterious black shape at the end of my bed, just standing there. It so freaked me out that I told Ozzy about it the next day, and he came up with the lyrics. I was really into the supernatural and spiritualism, and things like that happened to me all the time.”

What drove the album was the unique instrumentation - with Iommi’s guitar sound especially becoming a signature.

“I wanted as much distortional as possible, when everyone else was going for a clean sound all the time. It used to horrify amplifier companies, because they didn’t get what I was on about. Everyone was trying to reduce the distortion, whereas I was going the other way.”

“Bands ask me all the time how I got my bass sound,” says Butler, “because they wanna copy it. That’s easy. Just have three speakers in a four-speaker cabinet, and turn everything up so loud that you blow the lot!”

The reaction to the album at the time was mixed. While some loved it, others were far from convinced. Iommi recalls one particularly vehement critic of the record.

“I read at the time about Roger Waters from Pink Floyd’s attitude. He utterly loathed what we’d done. He thought the album was total crap, and predicted that both it and us would quickly disappear. I must admit that made me laugh at the time - and still does.

“What do I think of the album now? I like it. Yes, it could have been better, and I can hear things that shouldn’t be on there. But you can sat the same about any of our records. What it does do is capture the energy and power of the band back then. And there are people trying today to get the same atmosphere.”

Perhaps it’s Ozzy Osbourne who best sums up what the album means, and why it’s become the holy grail for metal.

“You know, the four of us have fallen out over the years. But all I need to do is go back and listen to this album to realise just how much I love the other three. It’s just magic. I can’t put it better than that. I’ve been lucky in my career to have played with some great musicians. But, with great respect to all of them, this was the best of times for me. That album was so special, and changed all of our lives forever. Whatever I’ve been lucky enough to do, and the same goes for the other three guys, we owe it to that record. There were no egos, just four friends who meant the world to one another.”