As the helicopter bearing them south flies high above the sun-baked deserts and mountains of San Bernardino County, four young Englishmen take turns to dip plectrums and penknives into a bag containing an ounce of high-grade cocaine. It’s the afternoon of Saturday, April 6, 1974, and the members of Black Sabbath are preparing, in their own inimitable way, for the biggest gig of their career.

By any measure, the inaugural California Jam was a huge undertaking. A 12-hour rock concert, co-headlined by British giants Deep Purple and Emerson, Lake & Palmer, and featuring rising stars the Eagles and Earth, Wind & Fire, the event was to be broadcast across America by ABC Television and aimed to attract the largest-paying audience ever gathered in one place. That just three years on from their debut American gig, a shambolic show at a rundown Staten Island theatre, Black Sabbath were to occupy a slot third from top of the Cal Jam bill, was an indication of both their burgeoning popularity among American rock fans and their growing reputation as one of the must-see live bands of the era.

One might reasonably expect, then, that spirits would have been high in the Sabbath camp on this momentous day, but in reality Ozzy Osbourne, Tony Iommi, Geezer Butler and Bill Ward were jetlagged, pissed-off and nervous. Just 48 hours earlier the quartet had been at home with their families in Birmingham, under the impression that their booking agent had removed them from the bill as a dispute between the co-headliners as to who should close the show threatened to derail the entire endeavour. It was only when the promoters informed Sabbath’s management that the quartet’s non-appearance would result in a $250,000 lawsuit that Tony Iommi was hurriedly tasked with waking his disbelieving bandmates in the dead of night to inform them that they needed to be in Los Angeles on the next outgoing flight. Exhausted and under-rehearsed, the quartet were placing their trust in cocaine and adrenaline to get them through the day.

“We’d been touring non-stop for fucking years so we really needed to take a break,” recalls Ozzy. “And because we hadn’t seen one another for a couple of months, we hadn’t rehearsed. I remember we had to do a run-through of our set in a hotel room with the guitars unplugged, without any amplifiers.”

“So then to fly in at the last minute to the biggest venue we’d ever seen was a bit nerve-wracking,” admits Tony Iommi. “I remember being terrified, because it was being broadcast live on TV and radio across the States, and we knew that what we did on that stage was going to be documented and shown for the rest of our lives.”

When their helicopter touched down at the Ontario Motor Speedway track, the musicians saw four black limousines waiting to ferry them to the stage. As a symbol of just how far the quartet had travelled from their working class roots in poverty-stricken Aston, the image was striking.

The band’s nerves were hardly helped by a false start to the show. Such was the overwhelming noise of the welcome Sabbath received from the 200,000-strong crowd upon walking onstage, that Bill Ward’s voice cracked as he attempted to cue in the band for Tomorrow’s Dream, and he had to start the count a second time. But for the hour that followed, Sabbath barely put a foot wrong, wowing those gathered in their masses (and a spellbound audience tuned in across America) with an inspired 12-song set – Sweet Leaf, War Pigs, Supernaut, Iron Man and Paranoid included – which threatened to shift Southern California’s tectonic plates. As the sun began to dip, the crowd rose as one to welcome the band back onstage for an encore of Children Of The Grave: the frustrations of the past few days were forgotten and the four musicians exchanged broad smiles.

“I don’t really remember much about the day because I was coked out of my head,” admits Geezer Butler with a wheezing laugh. “We were all totally out of our skulls. But afterwards you think, ‘Yeah, that wasn’t bad.’ We were a band that was given no chance, told to go and play ‘proper’ music, so days like that felt like we’d beaten all the odds.”

Beating the odds has become a trade-mark that has come to define Black Sabbath’s entire career. Over the better part of five decades, they have defied every critic, every challenge and every disaster that has come their way, carving out a legacy that sees them stand, indisputably, as the single most influential and important heavy metal band in history. And yet, with the September 3 announcement that Sabbath are set to embark upon their farewell tour, fittingly titled The End, in January, the unimaginable is soon to become a reality: Black Sabbath are done.

When Ozzy, Tony and Geezer walked from the stage of the British Summer Time festival in London’s Hyde Park on July 4, 2014 at the end of the final show on a year-long promotional trek in support of 13, the first Sabbath album recorded by the trio since 1978’s Never Say Die, no one actually knew what the future held for Black Sabbath. In their heads, each of the three men harboured thoughts that this might be the end of the band, but none of them wanted to put such thoughts into words. In truth, none of the three had expected that the campaign would have turned out to be such a triumph. A critical and commercial success, 13 had topped the album charts in the UK, US (a first for the band), Germany, Canada, Switzerland, New Zealand, Norway, Sweden and Denmark, and the tour that followed found Sabbath playing with a power and authority that made a mockery of their veteran status. That the band had pulled this off while guitarist Iommi was battling cancer only sweetened the sense of achievement. So, perhaps understandably, no one wanted to pop the champagne bubbles by asking ‘What now?’

“I think Tony might have said something in the press that the last tour was the final tour, but that was more Tony thinking aloud as he was worried about his cancer, so it was never official,” says Geezer. “It didn’t have that finality: we all thought it might be the end, but none of us said it to one another. So then Sharon [Osbourne] mentioned the possibility of doing one final, farewell tour so that everyone knows this is it, and we were all up for that. Now that we’ve all decided this, we can all walk away happy.”

Given that they’re set to lower the curtain on a musical venture that has occupied much of their adult lives, one might expect that this would be an emotional and difficult time for the trio. But over the course of three separate phone conversations, a different picture emerges. There’s a sense of sadness, for sure, but beyond that, each man exhibits an enormous amount of pride and respect in what their collective efforts have achieved. Given the somewhat turbulent nature of their shared history – the fistfights and fallouts, the swindles and scams, betrayals, broken promises, addiction and adulation – it’s evident that they are genuinely delighted to have the opportunity to close the book on Black Sabbath on their own terms.

And while the prospect of embarking upon a final tour has naturally engendered mixed emotions, its announcement, the trio concede, brings a welcome clarity to a previously uncertain situation.

“It was just time, really,” says Ozzy. “It’s done, we’re done. I can’t complain – we’ve had a great run. I’m just happy we’re ending on a high note, and going out as friends.”

“As much as I wish we could, we just can’t go on forever,” agrees Tony. “It’s going to be strange, and difficult, but you have to stop somewhere. I love being onstage and I love playing with the guys, and it’s not that I want to stop, but the touring is physically tiring for me, and indeed for everybody; I would honestly be worried about getting really ill again.

“But I think the fans deserve another chance to see us, and it’ll be nice to go out and finish it off properly. We couldn’t wish for better fans and hopefully we’ll be leaving them with memories that’ll last a lifetime.”

Rehearsals for Sabbath’s victory lap, a trek promoters promise will “surpass all previous tours with their most mesmerising production ever”, are due to commence in Los Angeles – where Ozzy, Geezer and touring drummer Tommy Clufetos reside – later this month. The End will begin in Omaha, Nebraska, on January 20, with engagements in Australia, New Zealand and Europe (including a return to Donington Park for a Download headline appearance on June 11) set to fill the band’s diary until mid-July. While discussions about a definitive setlist are still ongoing, Ozzy is promising a classics-heavy selection that will “take fans back down memory lane”, and undoubtedly prove emotional for the men onstage, too.

“I’m sure that the closer we get to the end, the more nostalgic we’ll be,” admits Tony. “It’s been quite a trip…”

Ask the members of Black Sabbath to choose specific highlights of their eventful, storied career and you’re faced with lengthy silences from three musicians who’ve never been wholly comfortable with bigging up their own legacy.

“Everyone has got their own favourite Sabbath album, whether it be Vol. 4 or Master Of Reality or whatever, but I honestly don’t remember making those albums, because we were all so fucked up!” Ozzy admits with a laugh.

When pressed, though, the trio offer up the memory of convening in their then-manager Jim Simpson’s Birmingham home to receive their own vinyl copies of the first Black Sabbath record, just one week ahead of its February 13, 1970 release. Asked for his thoughts upon hearing Sabbath’s music on vinyl for the first time, Tony modestly offers the opinion that “it’s not a bad album”.

“A lot of the initial reaction was, ‘Oh, what’s this bloody racket?’” he laughs. ”We were coming up with something so different from the music that was around, that it was bloody hard at times to battle through all these barriers. But I think we were all excited that we could finally touch and hold our own album.”

“I opened the album, saw the upside-down cross and thought, ‘Oh God!’ because I knew I couldn’t bring it home; my family are strict Irish Catholics and my dad would have gone mental,” Geezer notes. “But it was great, because we finally had something tangible that we could take to all the naysayers, to say, ‘Look, we’ve finally done something’.”

“Nobody believed that we’d ever do anything. And we didn’t either, really. We thought we might get to do an album or two if we were lucky, and then we’d have to get proper jobs. Because we’d been turned down by so many record companies, told to come back when we could play our instruments – all the insults you could think of, they’d say to your face. We’d do showcases for record companies and they’d walk out after the second song. So it was a real battle trying to get that album done. And then when it came out, all the press hated it and slagged it off. It really was us against the world.”

A few weeks later, Black Sabbath was in the Top 10. No one was more surprised than the band. By June, they were back in the studio. Afforded five days to record their second album – a luxury compared to the 12-hour stint at Regent Sound Studios which spawned their debut – the musicians were bemused when producer Rodger Bain informed them during the final day’s session that they still needed two and a half minutes of music to fill out the tape. Just 30 minutes later, guitarist Iommi presented the band with a hastily assembled new composition, a track lyricist Geezer Butler would christen Paranoid. Released as a single in August, the track crashed into the pop charts at Number 4, turning four bemused Brummies into the nation’s newest and most reluctant pop stars.

“God, we couldn’t believe it,” Tony recalls. “We hated being pop stars. That really wasn’t us, wasn’t what we were aiming for. We’d do Top Of The Pops to a load of screaming kids, and feel so awkward. We were thinking, ‘Oh no, this is not the band we want to be.’”

As their success grew, the next few years flew by in a blizzard of cocaine, sex, alcohol, acid and amphetamines.

After 1971’s Master Of Reality album became the group’s first US Top 10 hit, Sabbath effectively relocated to the US, renting a huge mansion in Bel Air, which quickly acquired a reputation as the most decadent party pad in Los Angeles. In the midst of this chaos, the quartet recorded two of their finest albums, 1972’s Vol. 4 and ’73’s Sabbath Bloody Sabbath, and with their stunning California Jam performance in the spring of 1974, Sabbath seemed to have America at their feet.

The party couldn’t last, however. Curiously, the band’s triumph at the Cal Jam, broadcast into every home in America, didn’t translate into a sustained sales boost for the quartet, and though it featured two of their finest compositions, Hole In The Sky and Symptom of the Universe, 1975’s Sabotage album became the first Sabbath album to fail to hit platinum status in the US. The group became mired in a bitter, protracted legal dispute with manager Patrick Meehan, and their drug use escalated alarmingly. Technical Ecstasy, the band’s seventh album, was a creative and commercial disaster, and Sabbath were beginning to look increasingly irrelevant and impotent. Ozzy actually walked out of the band in 1977, but returned ahead of the recording of Never Say Die!, an album whose defiant title was horribly betrayed by the flaccid material it contained. When the group attended Warners’ launch party for the album, they were embarrassed to find Bob Marley’s Exodus playing over the PA, and young record company staff wholly unaware of their identity. Further humiliation was to follow, as the quartet limped through an eight-month world tour with effervescent labelmates Van Halen, seemingly unconcerned that the younger band was stealing their thunder almost every night. The tour’s final show, on December 11, 1978, would mark the first ‘last gig’ for Sabbath’s original lineup.

“It was a really hard time,” Tony admits. “There were too many drugs involved, and drink, and we weren’t communicating. Ozzy would disappear for days on end, and when he did show up he wasn’t interested in singing, and it just became a shambles.”

“Ozzy was going nowhere at the time,” recalls Geezer. “He hated the music, and didn’t want to do anything, except do as much coke and drugs as he could do, and get as drunk as he could. When we got together to do the final album, as would have been, Ozzy turned up about four weeks after we’d got to LA to start writing the album. He turned up out of his brains, having been kicked off the plane after chinning someone, and we thought, ‘Oh no, we can’t go through all this again.’”

“We knew we had to do something, that we couldn’t carry on like this,” says Tony. “And then Bill decided to tell Ozzy and that was it.”

“I actually cried when Ozzy left the band,” admits Geezer. “It was a really hard decision for all of us. But it was the best thing we could have done for Ozzy. He was completely out to lunch; I don’t think he’d have lasted much longer if he hadn’t been pushed out.”

The years that followed have been well documented. Remarkably, from this painful nadir, both parties rallied. Sabbath recruited American vocalist Ronnie James Dio and delivered, with 1980’s Heaven And Hell, one of the finest albums in their canon. Ozzy, meanwhile, was saved from self-destruction by Sabbath manager Don Arden’s daughter Sharon, and launched a hugely successful solo career with the brilliant Blizzard Of Ozz and Diary Of A Madman albums, aided and abetted by elfin LA guitar hotshot Randy Rhoads. A 15-minute Sabbath reunion at Philadelphia’s John F. Kennedy stadium on July 13, 1985, sandwiched between Billy Ocean and Run-DMC as part of the Live Aid global jukebox, only served to emphasise the complete absence of chemistry between the estranged bandmates. And that, really, should have been that. Yet Sabbath would rise again, aided by an unexpected boost in their credibility in the late 80s and early 90s, as emerging acts such as Metallica and Pantera, Soundgarden and Alice In Chains credited the band’s first six albums as the foundations of their own sound, helping to reintroduce the veteran group to a whole new generation of music fans.

“It took a long time for people to realise that we had done something different and real and from the heart, so when the Seattle bands named Sabbath as their big influence, suddenly we were cool,” Tony says with an ironic chuckle. “I didn’t even care about being ‘cool’, I just wanted to play guitar. But it felt like a kind of vindication.”

In taking on the challenge of recording a new album in 2012, Osbourne, Iommi and Butler were only too aware that they were running the risk of pissing on their own legacy. The subsequent critical acclaim and commercial success which greeted 13 was welcome, but beyond cold industry statistics, it’s the trio’s immense satisfaction in pulling off such a triumphant comeback which resonates most clearly today.

“Getting back together again to do that album was such a good time, there was a great vibe and everybody appreciated the opportunity to get into it again,” reflects Tony. “It was just a really nice feeling that everyone was so into it. Obviously with me going through the cancer thing at the time it made everyone think, ‘Oh blimey, this could be it’, so it put everyone on the same page and made us all fight together. It really felt good.”

Such was the positivity around the band’s return, that, as outlined by Ozzy to this magazine in September 2014, plans were put in place for the band to return to the studio with Rick Rubin early in 2015. Those plans though, have, for the moment at least, been put on ice.

“For us to do another album would take four years and by the time we’d finish it we’d be in our early 70s… and you don’t know if we’d even finish it,” Ozzy reasons. “With the time it takes, and with Tony’s health thing, with not knowing whether it’ll come back or not, you just don’t know. So we just want to go on our last hurrah without worrying about that.”

“I was all up for doing another album to be honest,” Tony admits. “I’d written a lot of riffs, and had a lot of ideas, and was raring to go. But if everyone is not on the same page in terms of wanting to do one… Geezer wasn’t so keen, fearing it would be rushed, and I think he was right. But I’d love to do another album, so if people are interested after we finish the tour…”

If Black Sabbath’s turbulent history has taught us anything, it’s to say ,‘Never say never.’ For now, that particular closing chapter of the band’s story, if there is to be one, remains unwritten. There is, we have to note, one rather large elephant in the room when it comes to celebrating Sabbath’s farewell however, and that concerns speculation – stoked by his appearance in April along Iommi and Butler at the Ivor Novello Awards in London – as to whether Bill Ward, Sabbath’s only currently estranged founding member, will be invited back into the fold one more time. When the question is put to Ozzy, the singer sighs with obvious exasperation.

“I can’t answer that question,” he says flatly. “If I start talking about Bill he starts to get irate, so let’s move on.”

Pressed on the same question, Tony diplomatically notes “it’s in the lap of the gods”, while Geezer is rather more forthcoming:

“It’s a shame that he’s not with us,” he admits, “that would have been the ultimate thing, to finish it all off with Bill. I’m still not sure what happened with the whole thing…”

That particular question will doubtless rumble on right through to Sabbath’s final-ever show. But with rehearsals yet to start, and the prospect of a year on the road ahead, for now, Ozzy, Geezer and Tony aren’t gazing too far into the future. Stoic working-class Brummies, the three friends aren’t shedding any tears when considering the dissolution of their union, and all three men are at pains to point out that the end of Sabbath won’t mean an end to their individual musical careers. But one thing is certain: they’re going to miss this band when it’s gone. And so, obviously, are we.

“We were four lads from Aston, Birmingham, who said, ‘Let’s have a crack’, and we did great,” says Ozzy, when asked to consider the band’s legacy. “People loved this band, and they still do, with new fans discovering us all the time. It’s amazing to consider that.”

“It’s unheard of now for four people that lived two streets away from one another to get together and be in a successful band,” says Geezer. “But it all fell together like some act of God.”

“We’ve made a good mark,” says Tony. “I think people will remember us, and respect us. I’m proud that we’re still here, and still capable of doing this.”

“But this is it,” promises Ozzy, with finality. “The End. So please do come along, we would love to see you.”

Black Sabbath will headline Download on Saturday June 11. See Blacksabbath.com and Downloadfestival.co.uk.

Read our interview with Bill Ward here.

California Screaming

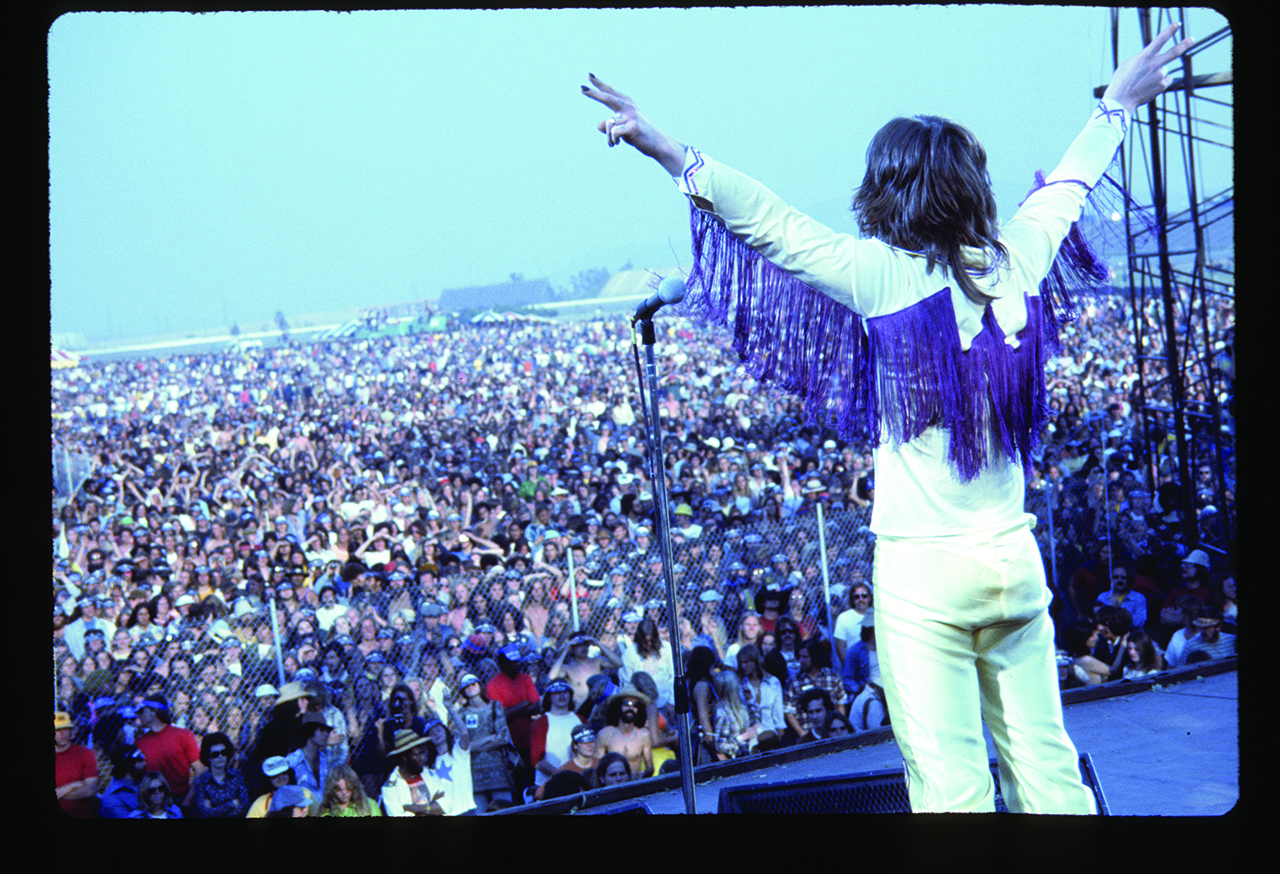

The sights and sounds of California Jam had such an impact on Sabbath superfan Allen Pamplin that he founded a fan club to celebrate its memory. He remembers all the action from that seminal day…

“I’ve been a Sabbath fan since 1973. My older brother had a friend move into our house, and he brought with him his record collection. He turned me on to Sabbath’s Master Of Reality. The first song I heard was Sweet Leaf, and the rest is history.

“California Jam was my first Sabbath show in front of their largest crowd. It was fucking loud as can be next to the stage, and the sound was clean. 54,000 watts of Sabbath! Just awesome! Sabbath were unprepared for this show – it was at short notice, they had no practice, and came straight from the UK to California. They were playing on the edge.

“The crowd was reacting before Sabbath even hit the stage. Everyone knew they were up next. As the stage rolled out – the two stages were on railroad tracks – the first thing that stood out at me was Bill’s red drumkit up on the riser adorned with carnation flowers all over it. It was absolutely beautiful! It looked like a funeral. When the stage was finally in place, a surge of energy came from the back of the large crowd, about 200,000 strong. Everyone far from view wanted to get a better look and started lunging forward. It built up like a fricken tsunami. By the time it reached us up front near the stage, we were literally slammed from behind into the person in front of us. We were all being squashed like sardines, and the press enclosure fence next to the stage started to lean. It was getting harder and harder to breathe. Don Branker was the MC for the event, and after five minute of pleading with the audience, they did eventually back off. Thank God!

“During Children Of The Grave, Ozzy got everyone to get their arms in the air, like 200,000 pulsating peace signs pounding to the music in sync. The crowd was electrified. You didn’t care how uncomfortable you were in the crowd, we were all touching the sky. It was fucking unforgettable!”

For more, check out the California Jam Fan Club on Facebook