The collaboration between Steven Wilson and Aviv Geffen, otherwise known as Blackfield, looked like it was over in 2014 when Wilson announced he was leaving it behind. But the pair returned with Blackfield V in 2017. Geffen wistfully described it to Prog as a “failure album”.

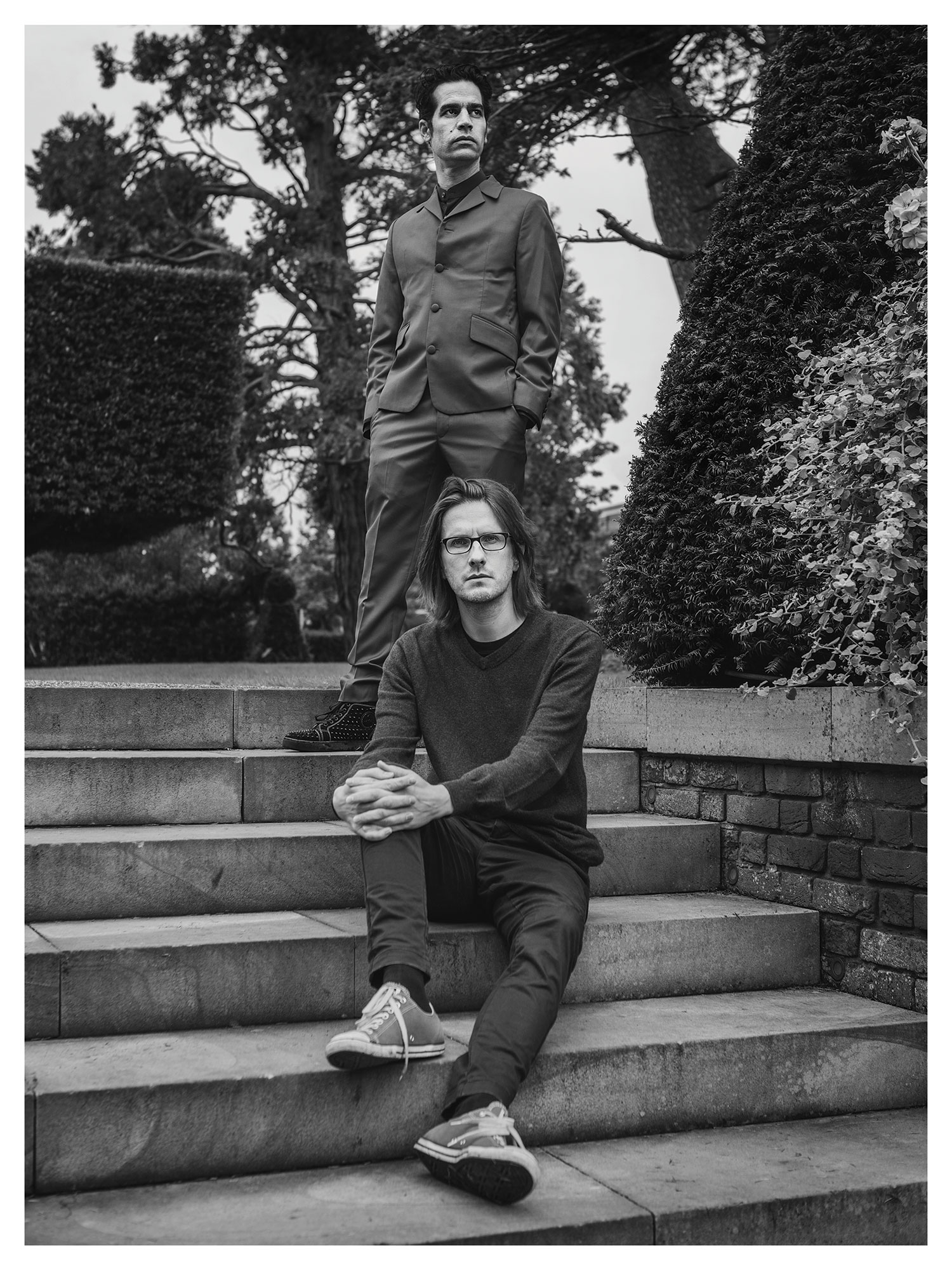

Blackfield, the band comprising prog Übermensch Steven Wilson and Israeli musician Aviv Geffen, have reconvened four years after their last release to make a majestic, widescreen, lushly uplifting album about being resigned to the notion that they will never achieve their goals. Geffen is in a London hotel room talking to Prog, while his nine-year-old son Dylan plays in the background.

“It’s about both our lives,” he says of himself and Wilson, casting a glance over his career and his early days as an inflammatory rock politico, who emerged 20 years ago as an agent of change, not to mention an outspoken, even outrageous character in his somewhat conformist home country.

“When I started as Aviv Geffen, I was like the John Lennon of Israel. I felt like I could change the government. Of course I keep fighting, but this album is like admitting we are only all idiots in the crowd. It’s like a ‘failure’ album, where we admit we won’t be massive rock stars – not Steven, not myself.”

Blackfield V is full of such wistful regret. On the closing track, From 44 To 48 – a sort of prog ballad version of Frank Sinatra’s It Was A Very Good Year – Wilson sighs, ‘I knew I’d left it far too late,’ while during the keening bombast of Family Man, Geffen owns up: ‘It’s not a shame to be a family man.’

“Exactly,” he says. “I can be a great dad, but I won’t be the next Kurt Cobain.

“This album,” he continues, “is very down-to-earth. It’s someone saying, ‘Look, I’m a big failure.’ Which is nice, you know?”

He can handle that? “Oh, yeah.”

He is, as the sweeping, symphonic opening track has it, just A Drop In The Ocean?

“That’s what Steven and I believe, yeah. “I think,” adds Geffen, “Steven and I are like outsiders. I don’t think Steven gets the respect he needs.”

If Geffen’s being honest, he doesn’t believe either of them do. Despite being rapturously received in prog land, both Wilson – who considers himself at best a big cult artist, lacking the wider approbation of the mainstream – and Geffen, who has made no bones about his desire to be taken seriously outside of his homeland, have expressed their dissatisfaction with their current positional status.

“Right,” Geffen says. “Look, when Bono asked me to open for U2 [in Athens, in 2010], I felt like a king for one day. But I think Steven and myself, we hope to be more.”

It seems a strange thing to say, at least this writer thinks so. The last time Prog saw Geffen was in 2007. He had invited us onstage with him during one of his gigs outside Tel Aviv. It was to demonstrate the extent of the fandemonium, to show what it was like to perform before 15,000 screamingly ecstatic Israelis.

“Israelis, yeah,” he says, dismissively. “Blackfield should get bigger crowds. I don’t think we’re less talented than many bands…”Geffen, who beside his rock star status at home is one of the judges on the Israeli version of television singing contest The Voice, weekly attracting a million viewers, leans forward.

“I dunno, in Israel I’m still something – I don’t want to say ‘symbol’ – but Steven deserves much more.”

But, Prog argues, Wilson regularly sells out London’s prestigious Royal Albert Hall…

“I think he deserves more – Wembley, really,” Geffen parries. “He’s one of a kind. I tell my son Dylan that Steven is like the new Jimmy Page or King Crimson. For me, I feel like I’m working with a [Dave] Gilmour or Page when we’re in the studio.”

With Blackfield V, a sweeping, flowing 45-minute ocean-themed song cycle, they’ve created an album that’s ostensibly about failure but is designed to succeed, with its rousing choruses and grandiose production – which, in the case of three of the tracks, was courtesy of Alan Parsons. The latter came to Tel Aviv to record, while other sessions, over a period of 18 months, took place in LA, London and Wilson’s home set-up in Hemel Hempstead. There was assistance from Tomer Z on drums and Eran Mitelman on keyboards, and string arrangements by the London Session Orchestra, leaving all other vocal and instrumental duties to Wilson and Geffen.

Parsons, lest we forget, was the engineer at the controls of The Beatles’ Abbey Road and Pink Floyd’s Dark Side Of The Moon, two of the touchstones for Blackfield V. Meanwhile, David Bowie’s pianist Mike Garson contributes magniloquent flourishes to the beautiful October. Wilson, Parsons, Garson – Blackfield V, for all its concise melodies and tight musicianship, is a veritable prog-fest.

“October is great: Steven sent me the mix and I cried,” reveals Geffen, who says Wilson “fell in love again” with Blackfield – he had been getting less and less involved with the band and declared his intention to quit following 2013’s Blackfield IV to focus on his solo career. “Now,” says Geffen, “it’s like a full partnership again.” He couldn’t be happier. “He [Wilson] just loved the album. He said it’s the best one we’ve done so far.

“The blend between us is the whole point,” he adds. “We can’t exist without each other.”

Is it a temporary reunion? “No, it’s forever. Really, we were never apart.”

All that Geffen has to do now to keep the relationship buoyant is contain Wilson’s urge to extrapolate. “I prefer Steven when he came out with [Porcupine Tree] albums such as [1996’s] Signify and [2002’s] In Absentia, which were short songs. I think he’s an amazing musician. I’m just not a big fan of long solos…”

Didn’t he “ban” Wilson from doing them a couple of Blackfield albums ago?

“Yeah,” he says, laughing.

Wilson, with his producer’s ear, once compared and contrasted his approach with that of Geffen’s, the melodist and lyricist. It explained why the partnership works.

“Aviv is a songwriter and a performer and not a producer,” he said. “Songwriters tend to come in, as Aviv does, with a demo of a great song that has the shittiest guitar sound on earth. Those things don’t matter to great songwriters, and it’s up to me as a producer to say, ‘Great song, but let’s try this guitar tone,’ or, ‘Let’s try these sounds.’

“Aviv is committed to the idea of the perfect rock or pop song. I, on the other hand, bring to that my interest in creating sound worlds, textures and these big productions. That’s the balance of the relationship.”

Some of that language does seem quite combative. How frictional do things get in the studio?

“We’re best friends so that makes Blackfield very homey and family-ish,” Geffen reassures us. “We’re laughing all the time.

“Steven,” he adds, “has the last word, with all the guitars and mixes and sounds, and I’m in charge of the keyboards and the orchestra. So everyone gets his own space. Blackfield for Steven is the best escape. We’re not really prog, and we’re not really jazzy. It’s songs. I think all our fans see Blackfield as a continuation of Porcupine Tree. If they like Signify, they’ll love this album.”

On We’ll Never Be Apart, there are a series of accusatory lines, sung by Geffen, contrasting the anguished singer ‘bleeding on the ground’ and the guitarist ‘juggling your guitar’, whose ‘crowd wants some more.’ ‘But,’ he cries, ‘we’ll never be apart.’

What’s that about, Aviv? “It’s a jealous song about Steven,” he confesses. “There was a moment when I was in Israel. There was something on the news, maybe against Benjamin Netanyahu, and all the right-wing stuff was on my head, and Steven texted me: ‘I’ve just done an amazing show in New York.’ I was like, ‘You fucker. I’m here, taking all the fire cos I want to live in Israel in peace, and you’re just making your stupid solo music…’ So I wrote this song about him.”

Does he know it’s about him? “Of course.”

What does he think? “He’s amazed.”

Has it made him want to become, like you, more politically engaged? “Me and Steven have many things in common, but I think the politics I deal with are the real shit.”

If their political roles differ, they share many things musically. Both agree that Blackfield V is the missing link between the Beatles ’69 and Floyd ’73. “In a way,” Geffen says, “it’s a tribute to our heroes.”

They might have just penned a virtual concept album about the notion of unfulfilled desire, but he’s confident enough to believe those heroes would be impressed with the end results. Given Alan Parsons involvement with them historically, have Messrs Gilmour and McCartney heard it, by any chance?

“No, but I’m sure they’d like it – they’re good songs.”

The other influence on Blackfield V, unexpectedly, are Norwegian teen-pop gods turned serious exponents of, well, euphoric melancholia, A-ha.

“I think they’re genius,” Geffen asserts. “It might take years for them to be recognised, but eventually, time will tell.”

Wilson concurs, although they do bitch back and forth about the relative merits of two of the biggest pop groups the late 70s. “I argue with Steven about who is better: The Bee Gees or Abba. I say The Bee Gees, he says Abba. We’ve been arguing about this for years… and the arguments are very loud.”

There’s another Blackfield paradox – the prog band who love pop – to add to the one about the would-be stadium rockers singing bravura songs of failure and regret. The album itself is almost one big paradox, with its bleak personal vision destined to appeal to the masses.

“Blackfield is the place I can cry,” Geffen admits. “I don’t need to be macho or a hero. It’s my dark room to cry in.”

Why so nihilistic suddenly?

“I believe life is all chaotic,” he considers carefully. “I’m trying to make sense of it, without any luck.”

But you’re successful! You’re on TV!

“So what? What is success?”

Good question. Geffen sighs.

“To be an artist, it’s really pathetic, I think,” he decides. “For me, Thom Yorke is a genius. Why does he need those claps at the end? Why is he repeatedly singing Creep, a song he hates? To get the kisses and the love. At the end, we all want love. Radiohead, even Bob Dylan – they try not to show this weakness. But we need the crowd.”