“We always had so much more in common with bands like Yes and Genesis… we wanted to see how far we could take an idea”: What Blue Öyster Cult thought of being called prog – and what they really thought of the More Cowbell sketch

They may have been called “the thinking man’s metal band” but comparing themselves to ELP, Jethro Tull and King Crimson, they assert there was a lot more progressive thinking going on than many realised

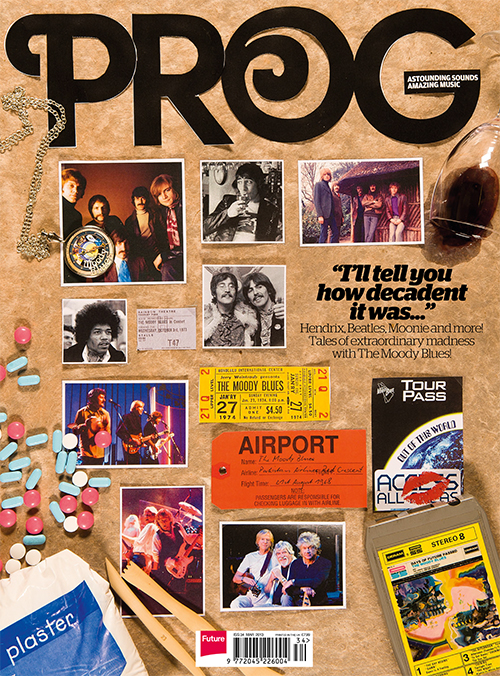

In 2012, with an expansive, 14-disc box set of their Columbia years just released, Prog reappraised the work of the band made infamous by bleakly comic songs like Joan Crawford, and a Saturday Night Live parody that went viral. We asked: how prog are Blue Öyster Cult?

During a career that spans more than 45 years, Blue Öyster Cult have often been referred to as ‘The thinking man’s metal band’. It’s an epithet that founding member Eric Bloom doesn’t reject – nor does he embrace it fully.

“We’ve been called a lot of things over the years,” explains the band’s veteran singer and guitarist. “Some of it’s flattering, and other descriptions leave me baffled. I suppose if you’re known as an intelligent band then that’s no bad thing. But are we metal? I’ve never been sure we fit into that category.”

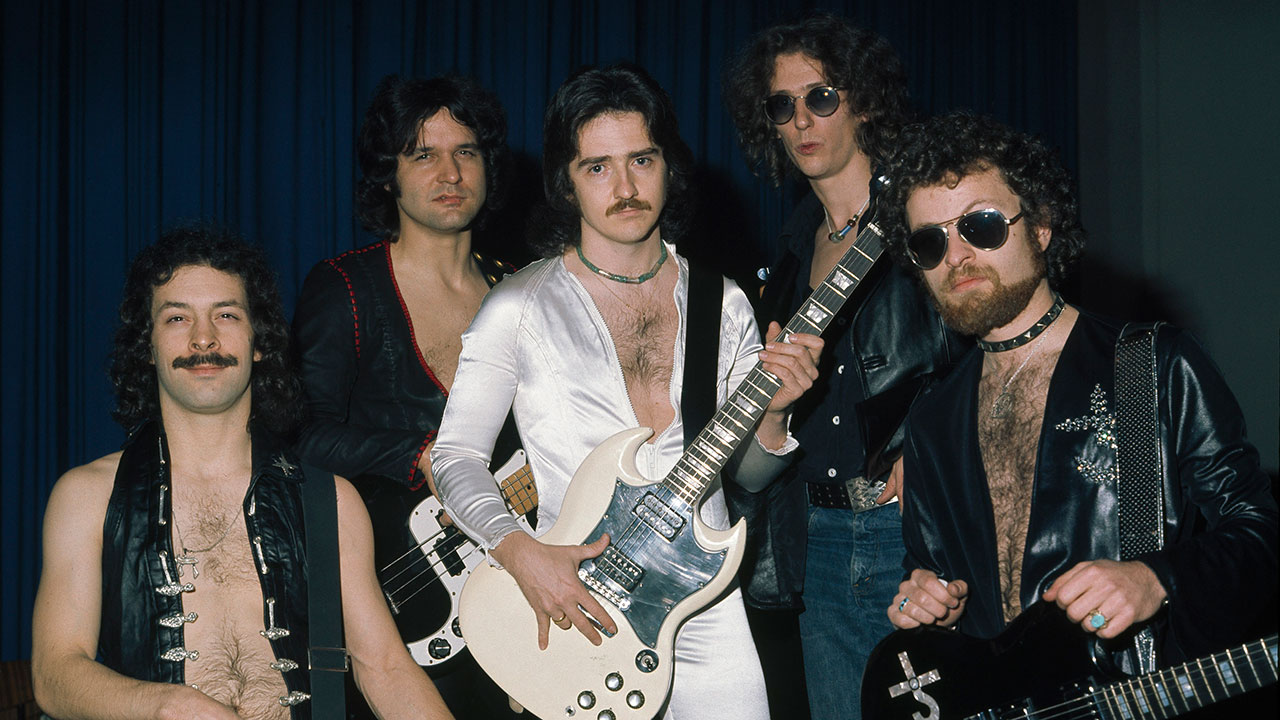

Since the band’s beginnings as Soft White Underbelly in Long Island in 1967, they have confounded and confused as much as they have delighted and inspired. They eventually became Blue Öyster Cult in 1971, a name inspired by a poem written by manager Sandy Pearlman as part of his Imaginos cycle (more of which later). By that time the classic line-up had come together, with Bloom and fellow founders Donald ‘Buck Dharma’ Roeser (guitar), Albert Bouchard (drums) and Allen Lanier (keyboards) joined by Joe Bouchard (bass).

“They really are a very intelligent band,” says Lifesigns keyboarder John Young. “That in itself puts them into the progressive end of music. And with their very melodic approach they’re accessible to those who like a good tune but also crave more sophisticated musicianship.”

Sel Balamir from Amplifier says: “Some bands are progressive because of their complexity. But other bands, like BÖC, are progressive because each one of their songs is distinct from each of their other songs in their repertoire. That’s the only way you can put out 14 albums. You’ve still got to have some interesting places

left to explore, and still have some interesting things left to do and say. And Blue Oyster Cult have always had something interesting to do and say.”

From the release of their self-titled 1972 debut album, there was always something a little different about Blue Öyster Cult, and the connection to the world of progressive rock was clear in their music, as well as the diversity of the influences they displayed.

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

“We weren’t like a lot of other bands at the time who wrote just about their own experiences,” says Bloom. “I was heavily into science fiction and fantasy, Albert was fascinated by poetry, and Allen had been hanging out with avant-garde musicians like John Cale. What we brought to the band was a sense of experimenting, and in that regard we always had so much more in common with bands like Yes and Genesis than Black Sabbath, because we wanted to challenge ourselves and see how far we could take an idea.”

Just how brilliantly individual the band could be is obvious on perhaps their most celebrated song, the 1976 hit (Don’t Fear) The Reaper. Written by Dharma, it includes a Latino-spiced jazz-rock section that takes the track beyond usual confines of a chart success. And even the lyrical imagery is slightly left-of-centre.

When we found ourselves being portrayed as hating what SNL did, I related to the way Emerson, Lake & Palmer or Yes were treated

Buck Dharma

“It was partially inspired by Romeo And Juliet,” recalls Dharma. “I was thinking about the concept of an eternal love, one that transcends the borders of death. While the original riff and idea for the song just came to me, when I sat down and analysed what I’d done it was clear to me that I had been subconsciously thinking of the way a band like Jethro Tull or King Crimson would tackle the composition. I wanted it to be so much more than a pop hit. I felt it needed the imprint of having a depth to it. I don’t believe it would have been so enduring if it had just been a throwaway composition.”

The song was so huge and so intriguing that it captured a new audience’s imagination all over again in 2000 when spoofed on the US comedy show Saturday Night Live in a sketch called More Cowbell. It’s always been claimed that BÖC were less than amused by the skit, and that they somehow felt their intellectual integrity had been compromised. But Bloom refutes this.

“We all thought it was hilarious,” he asserts. “And to this day, I love watching it. The problem is that we are seen as being humourless, which is nonsense. We enjoy having a laugh, even at our own expense.”

“When we suddenly found ourselves being portrayed as hating what SNL did, I related to the way Emerson, Lake & Palmer or Yes were treated,” says Dharma. “They were all thought to be too self-absorbed and full of their own importance – and that was never true. Like these guys, people didn’t want to admit that Blue Öyster Cult had any sense of humour. But, come on, how could you ever take a song like Godzilla (from the 1977 album Spectres) or Joan Crawford (from 1981’s Fire Of Unknown Origin) seriously? We were parodying and poking fun.”

Bloom further believes that the band’s relationship with prog comes with a desire to never stand still. “We have never wanted to repeat ourselves. Sometimes that shot us in the foot commercially – had we been prepared to get into the habit of using a successful musical formula, we might have been a lot bigger. But that would have gone against everything we stood for. What would be the creative point of just writing the same songs over and over again? We’ve always wanted to set our imagination free, to allow ideas to take the shape they demand, and to let the music flow. If that meant a song like Astronomy (from 1974’s Secret Treaties) being over six minutes long, then that’s the way it had to be.

We spent far too much money on lasers. That’s typical of the way we were… Great for artistry, disastrous for your bank balance

Eric Bloom

“To some extent, we were lucky that in our very early days we got the chance to tour with The Mahavishnu Orchestra, and their joy in getting fully involved with the music and extending compositions onstage did have a bearing on the way our career had developed. Do we regret not selling many more albums? No. Ask a band like King Crimson whether they would sacrifice what they achieved musically for a few more million sales and you know what answer you’d get. The same is true of us, and if we had stuck to one dimension, then we’d probably have been long forgotten.”

Dave Meros, bassist with Spock’s Beard, gives BÖC credit for introducing him to progressive music. “Before I knew what prog was, I loved rock. Anything called rock I’d check out. That’s how I got into Blue Öyster Cult. I was heavily into what they did, and because they were so mature I found myself attuned to progressive music without realising it. They were always so much more than just another powerful rock band.”

Bloom believes that some of the collaborations they’ve had down the years have also helped shape their unique perspective. These include the author Michael Moorcock – who’s closely associated with Hawkwind – Patti Smith, writer Richard Meltzer, and Sandy Pearlman, who also produced all of the band’s 70s output.

“These are all creative people, and they’re also totally mad,” Bloom says. “That helps, because they opened us up to so many possibilities. And only the most narrow-minded of musicians would refuse to work with such an array of talent. We’ve always been open to those sorts of collaborations, in the same way that some progressive bands have worked with other talents. ELP and others have, for instance, brought in orchestras. We haven’t done that yet, but if it seems logical and affordable, then we’d happily do it in the future. The trick is to use your contacts to enhance your art.

“That also goes for our stage show. We used hand-held lasers in the late 1970s. They’d only just been invented, but we paid a fortune to be the first to use them in an artistic setting. They looked great, and got a huge reaction – but in retrospect, we spent far too much money on them. That’s typical of the way we were. If it enhanced what we did, then the cost didn’t matter. It must have been like ELP taking out a full orchestra on the road in America. Great for artistry, disastrous for your bank balance.”

In 1988 the band released the concept album Imaginos, regarded as one of their finest moments. It weaves a complex alien conspiracy theory into a rock opera. “It started out as Sandy’s idea,” Bloom says. “He had a folder of poems and lyrics that he said we could draw on at any time,. That’s where Astronomy originated. Then when Albert left the band [in 1981], he and Sandy worked on turning all these ideas into a coherent album. Imaginos was recorded in 1984, after signing to Columbia. But the label wouldn’t put it out – they never thought it had commercial potential.”

Eventually it was decided Imaginos was released – but only if it was under the Blue Öyster Cult banner, and members of the band were brought in to augment what had already been done. “It was supposed to be a double album, but was cut down,” says Bloom. “I did some lead vocals, while Buck, Joe and Allen also contributed. But we were really on the periphery of the main creative process. Columbia just thought the band name meant more than Albert and Sandy’s did.”

Pearlman and Bouchard had envisioned the concept spanning three double albums, but to date just the one record emerged. There is, however, more in the vaults. “I know for a fact that Albert and Sandy did record a complete second album. It must be somewhere, and perhaps one day it will come out. Those two deserve any credit for Imaginos – but I also know it’s an edited version of their imagination, which is a shame.”

The band have recently released The Complete Albums Collection, a box set containing all 14 Columbia albums, plus two CDs of rarities and radio broadcasts. The classic line-up reunited onstage in New York in December 2012 for the first time since 1985. So, what lies ahead for one of the most cerebral bands of the 1970s?

“Who knows?” laughs Bloom. “Our entire history has been about surprising ourselves. You never know, perhaps we’ll now do an album of Gentle Giant covers. Or maybe some young progressive bands will start doing versions of our songs, and we’ll get complimented for being prog icons!”

Malcolm Dome had an illustrious and celebrated career which stretched back to working for Record Mirror magazine in the late 70s and Metal Fury in the early 80s before joining Kerrang! at its launch in 1981. His first book, Encyclopedia Metallica, published in 1981, may have been the inspiration for the name of a certain band formed that same year. Dome is also credited with inventing the term "thrash metal" while writing about the Anthrax song Metal Thrashing Mad in 1984. With the launch of Classic Rock magazine in 1998 he became involved with that title, sister magazine Metal Hammer, and was a contributor to Prog magazine since its inception in 2009. He died in 2021.