"If you thought you were a bluesman, hearing the Red Devils would send you back to the woodshed in double-quick time. Listening to that record, King King, would yank anybody’s chains. I had a CD made up of just two of the tracks on a loop – Mr Highway Man and Automatic. It was on constant rotation in my car wherever I went" - Billy Gibbons, ZZ Top

When Rick Rubin left New York and headed west in 1988, he severed ties with Def Jam, the record label he’d co-founded and through which he’d launched the Beastie Boys, Slayer and Run DMC. A music freak with an instinctive knack for picking out maverick spirits, Rubin set up base in a gothic-looking mansion house in Hollywood and from there rolled out his second record company, Def American.

Cast in his own renegade image, it became a home for such disparate bands as the Black Crowes, Danzig and the Red Devils.

The Red Devils were Def American’s shooting comet. Signed to the label in 1991, they were the archetypal Rubin band – five greasers who roughed up the blues, they blazed a brief but brilliant trajectory. They made just one album, and backed both Mick Jagger and Johnny Cash, before crashing and burning.

Their end was sordid and senseless, a wretched mess compounded by the tawdry death of their frontman, Lester Butler, at the age of 38. Butler was mourned by fellow musicians as a great lost bluesman. Yet even in death he continued to stir ill will. The Devils’ former bassist, Jonny Ray Bartel, was initially reluctant to contribute to this article for fear that it would canonise Butler.

“My personal history with Lester ended up being really bad,” he said. “He became the worst friend and the most horrible guy you could imagine. I’ve had to work hard on forgiveness towards him.”

The Red Devils grew up out of The Blasters, a hot rod of a band who became a fixture on LA’s vibrant punk and rockabilly scene in the early 1980s. Their drummer, Bill Bateman, looking like he’d walked out of a Sun Records session three decades earlier, and commanding a wicked bare-boned groove, put together a blues-playing side group in 1986.

Initially called The Stumblebums and then the Blue Shadows, after a Blasters song, it was a loose collection of local musicians and jamming buddies. One of the guys who began sitting in with Bateman was Lester Butler, a surf bum who blew a mean harmonica.

Even then, Butler had a reputation for raising hell. He once told a journalist: “Remember in the seventies when they said cocaine wasn’t that addictive? I was a good argument against that bullshit.”

Butler was eight when he first picked up a harmonica, and was guesting with local pickup groups by the time he was a teenager. His earliest influences were America’s great bluesmen – such iconic figures as Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf and Little Walter.

“I can still picture Les, a skinny surfer boy with long blond hair, riding his skateboard around town while playing his harmonica,” recalls Butler’s sister, Ginny Tura. “I remember him playing Whammer Jammer by the J Geils Band. A crowd used to gather around him in the parking lot where we all hung out. He loved music, surfing, skateboarding, bike riding and smoking pot.”

In early ’88, the owner of the King King, a poky dive bar in West Hollywood that had once been a Chinese restaurant, asked Bill Bateman to put together a full-time group to headline a weekly Blue Monday gig. Their nightly fee would be $200 a man.

Retaining the Blue Shadows name, Bateman co-opted his roommate, Jonny Ray Bartel, a rake-thin rockabilly nut, into the band along with Butler. Jonny Ray’s elder brother, Dave Lee Bartel, joined later on rhythm guitar, supporting an ever-shifting assortment of hotshot lead players.

The Blue Shadows were already whipping up a storm at the King King by the time the elder Bartel enlisted. Each Monday night, a crowd would line up around the block to catch the band tearing through a set of blues covers on the tiny 12-by-15-foot stage. The Blue Shadows brought out Hollywood’s hipsters and beautiful people – wannabe stars and starlets and leggy models. In early 90, Bruce Willis, then still in the first flush of his Die Hard fame, began showing up and sitting in with the band.

“Bruce Willis is the only guy that could possibly play Lester in a movie,” Bill Bateman says today. “Lester used to take him out on the street and show him how to play harmonica. He was on the team.”

In Willis’s wake, a coterie of musicians trooped along to the King King: Angus and Malcolm Young of AC/DC, the Red Hot Chili Peppers and the Black Crowes all crammed into the club’s red fake-leather booths; Brian May of Queen and ZZ Top’s Billy Gibbons both got up to trade licks with the Blue Shadows.

One night, Billy Gibbons calls me out of the blue. He’s heard about this piece from Jonny Ray Bartel and wants to reminisce.

“Oh man, they were quite an outfit to be reckoned with,” Gibbons says, chuckling. “I was running hard at the time with one of the ZZ Top dancing girls – they called her the Alley Cat because she was always crawling about. She lived close by the King King, and I became a regular there on a Monday night. And who should I make friends with in those days but Rick Rubin. He was hanging out and took an interest in the band.”

By Jonny Ray Bartel’s estimate, Rubin came by the King King at least 60 times to scope out the Shadows. “I loved their raw blues power,” Rubin says today. “They were edgy, rocking and grooving. It was a fun vibe seeing them every week. I have great memories of that time.”

In early 1991, Rubin decided to sign the band to Def American. He had two provisos before doing so: that they get a permanent guitarist, and they change their name.

Through the blues grapevine the band heard of a whizz-kid guitarist from Denton, Texas, named Paul Size, a fresh-faced 19-year-old who played like a veteran from the wrong side of the tracks. Size drove to LA in his pick-up truck to audition, got the job and then moved in with Butler.

The Bartels had first played together in a high-school rockabilly band called the Red Devils. Spotting an old button badge of theirs one day, Rubin told them the name would sell more records than the Blue Shadows and to revive it. The producer also decided that a studio recording wouldn’t do his new pet band justice, so instead he set about taping them live over three consecutive Mondays at the King King.

The resulting record, also titled King King, and featuring pianist Gene ‘Fingers’ Taylor, was released in July 92. It collected together blues staples such as Willie Dixon’s She’s Dangerous and Chester Burnett’s Mr Highway Man alongside a handful of self-penned tracks.

It was hot, blue and righteous: Paul Size shooting sparks off the rhythm section’s laconic shuffle; Butler blowing up a storm and singing as though there were a hellhound on his trail. It was also entirely at odds with the musical temperature of the time – Guns N’Roses, Metallica and Nirvana were the reigning behemoths.

Rick Rubin was also then working on Mick Jagger’s third solo album, Wandering Spirit. He’d brought the Rolling Stones singer down to the King King to see his latest charges, and in May ’92 he got the two parties together at Ocean Way Recording in Hollywood for a now-legendary 13-hour session.

Jagger and the Red Devils cut 13 tracks that day, scorching covers of vintage blues tracks and all but one of them still officially unreleased.

“We got a late-night phone call from Rubin and were told to show up at the studio at 9am the next day,” recalls Jonny Ray Bartel. “Mick came in and played the original recording by Howlin’ Wolf or Muddy Waters or whoever, and we’d jam along to it through headphones. On the third runthrough, Mick would sing and we’d tape it. It was that quick and raw.”

“That session is incredible,” says Rubin. “You’d have to ask Mick why he never chose to release it.”

Flush from working with Jagger and with critical acclaim for their own record, the Red Devils set off on their first tour, criss-crossing America as the opening act for the Allman Brothers band, ZZ Top and Los Lobos.

It didn’t take long for cracks to appear. Let loose, the band ran wild – their singer wilder than anyone else.

“We were rowdy guys,” says Bill Bateman, cackling. “We went out for 120 days straight and there were all kinds of illegal things going on – drugs, fights, hookers, cops, jail, you name it. One of us was bound to end up dead. Lester had actually clinically died four times in previous years. On one occasion he woke up in the morgue with a sheet over his head. It was his opinion that he led a charmed life.”

Three months into the tour the band were in tatters. Dave Lee Bartel walked out after a show in Dallas, claiming Butler was paid double what the others got. They limped through the rest of the tour with a friend of Paul Size filling in and bad blood in the air.

“It got to the point where Lester was doing crack at every town we went through,” says Jonny Ray Bartel. “He’d stay up all night and listen to the board tapes of the gig we’d just done, and then go scream at Bill, the best musician in the band, telling him he was dragging. He basically just turned into this psycho drug addict who was never happy.”

Butler’s sister, Ginny, disputes this image of her brother. “Les had occasional lapses with drugs and alcohol, but for the majority of his professional life he was sober,” she insists. “The stress of being together with the band twenty-four-seven while touring was just too much for him. He was always a perfectionist with his music and he noticed when anything was off.”

When Butler returned to LA, he told Rubin he wanted to work with different musicians. Rubin humoured him by holding a series of open auditions, but then informed Butler he was only interested in the original Red Devils.

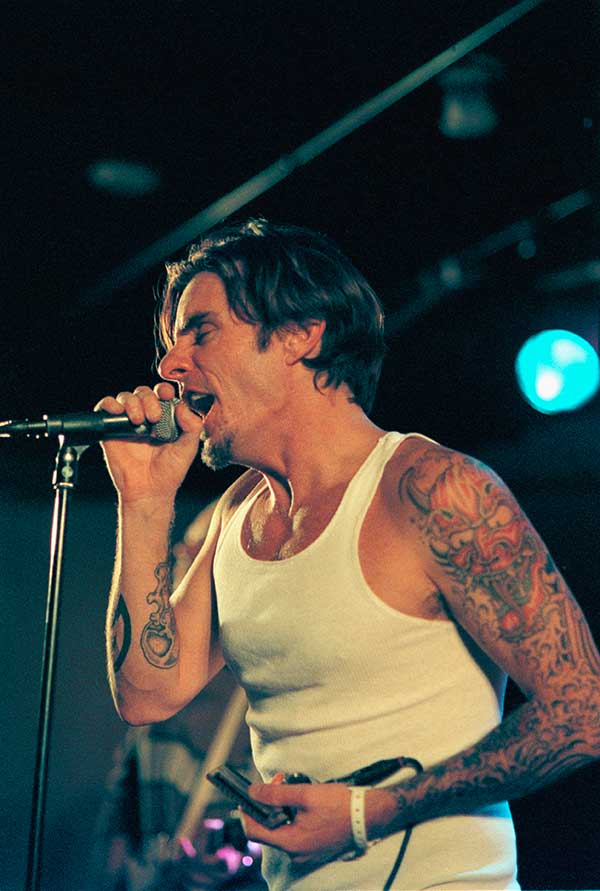

The patched-up band, with Dave Lee Bartel on board, toured Europe through the spring and summer of 1993, hitting a peak on an early afternoon slot at the Pink Pop festival in Holland (above). Pink Pop was the Red Devils’ valediction.

Then Paul Size quit, fleeing back to Texas, exhausted by sharing an apartment with Butler for two years. Rubin gathered the remaining members for one last great session at Ocean Way, backing Johnny Cash.

“He was a proper gentleman,” recalls Jonny Ray Bartel, “but the tracks sounded better with just him and his guitar, and that’s how Rubin put them out.”

It would be the last thing they did for Rubin. Soon after, they were dropped from Def American. They ghosted through a final European trek in 1994 and then split, beset by rancour and bitterness.

“Lester stole a bunch of money off us and wiped the band out,” claims Bartel. “We were broke and having to sleep on our fans’ couches. It was strictly his greed that took us out – that and drugs.”

“Lester had got back on the shit and he was a rookie,” says Bateman. “It was his first band, and he didn’t realise how hard it was to get five guys together that play that well. He tried to undermine it and it blew up in his face.”

Emerging from the carnage of the Red Devils, Bill Bateman returned to The Blasters, and the other three musicians to day jobs and part-time gigs. Lester Butler passed through short-lived groups and low-paid engagements in LA before gathering together a new band he called 13.

Mining the same blues seam as the Devils, they released a decent self-titled album in 1997 and had some success touring Europe.

“Lester’s reputation was a mess in LA. He’d done a lot of sub-par gigs and shown up in bad shape too many times,” says Alex Schulz, a seasoned blues guitarist who threw in his lot with 13. “For me, that band was a big step down in terms of business from what I’d been doing, but it was worth it to try and build this guy back up. When he was in good shape, Lester had some kind of magic. But he had big troubles in his personal life.”

13 bagged high-profile slots at blues festivals in Belgium and Holland in early May 1998. The shows were a success, but Butler was battling his demons, falling off the wagon after a stint in rehab. On the flight home, he told Schulz he’d hook up with a girl he’d just started seeing and buy an eight-ball of cocaine.

“He had five thousand dollars burning a hole in his pocket, and what he did was stay up for five days straight,” says Schulz. “I didn’t have the sense that he meant for it to end the way it did, but at other times he was pretty fatalistic. I think he felt there was a destiny he was living out – that he was going to go out that way.”

On the evening of May 8, 1998, Butler pitched up at Bill Bateman’s house in Hollywood. He was with another girl from the fast crowd he’d been running with.

“He’d been smoking rock, snorting coke, taking downers and drinking rum, so he was high,” remembers Bateman. “The two of them were sat in my living room and Lester was begging her for an injection of heroin, rather than snorting it like he had been.”

Bateman says he then left the house to go score his own heroin. He’d recently been convicted on a drink-driving charge, so was on foot and gone for more than an hour. When he returned, he says, Butler was still nagging the girl to shoot him up again.

“Eventually she did and he OD’d,” Bateman continues. “I was high myself by then and wasn’t paying them much mind.”

We may never know exactly what happened, as accounts differ, and by his own admission Bateman was worse for wear. Bateman recounts that the girl’s boyfriend came over, panicked, took Lester’s cocaine and shot it up through the veins in his hand.

“They had the idea that this would bring him back, and it killed him. They took him in his van to their house and he died there. After he’d been dead for eight hours they dropped him off at my place again, and I took him to the hospital. Then the cops turned up.”

Ginny Tura challenges Bateman’s account of her brother’s last hours and also the notion that he’d careered out of control. “Lester was sober for many years, and this relapse was fatal because his tolerance was low,” she maintains. “Bill did not make the emergency call when Les first passed out, and allowed two drug addicts to go off with his body. In my opinion he should have also done jail time.”

On the surface, the Red Devils’ legacy doesn’t amount to much – a solitary album and some celebrity fans. Yet King King has retained its power, and their influence lingers in America and especially Europe, where Lester Butler tribute acts continue to operate.

“The Red Devils is kind of a repeat of the thing people said about the Velvet Underground,” says JJ Perry, a South Dakota journalist and musician who runs nofightin. com, an online site dedicated to the band. “Their record didn’t sell, but it made a massive impression. Everyone I knew that heard it went out and formed a band.”

On November 12, 2013 Ginny Tura went out to dinner with her brother’s long-term girlfriend, Lori Peralta. It would have been Lester Butler’s 54th birthday.

“The Lester I knew and loved was extraordinarily witty, highly intelligent and charismatic,” says Tura. “He loved people and was constantly surrounded by friends and family. He could blow out birthday candles from across the room; we’d say he had harmonica lungs. Which of course he did.”

The men who shared the Red Devils’ short, crazy ride have a different recall of Lester Butler.

“He was a notorious addict,” says Jonny Ray Bartel. “And when you start messing around with heroin and coke, it’s a safe bet your heart and lungs are going to flip you out eventually. It didn’t shock me and I don’t remember a big emotional thing. I was just kind of numb.”

“Lester was an idiot, but I wish he wouldn’t have died,” concludes Bill Bateman. “I’ve searched the whole planet over and there isn’t anybody out there like him. Lester was the wildest one.”

This feature originally appeared in Classic Rock 195.

Postscript: In May 2017 Bill Bateman, Jonny Ray Bartel, Paul Size, and Mike Flanigin, alongside Dutch blues singer and harmonica player Pieter “Big Pete” Van Der Pluijm, reformed The Red Devils for a series of shows in The Netherlands, before joining ZZ Top as support act on the European leg of their Tonnage Tour.