Bringing It All Back Home, Highway 61 Revisited and Blonde On Blonde are the high-water mark of 60s rock, and with the quasi-religious reverence due them, they are referred to by Bob Dylan fans as the Holy Trinity. The three most sublime albums in rock were created in a 14-month period from January 1965 to March 1966. In November 2015, sessions from these albums were issued as The Bootleg Series Vol. 12: The Cutting Edge 1965-1966.

It came in three formats: the ‘best of’ consists of two CDs, the deluxe edition six CDs and the collector’s edition 18 CDs – “…every note recorded during the 1965-1966 sessions, every alternate take and alternate lyric”. All three formats contain liner notes, notes on the recordings and, in a separate book, a collection of photographs.

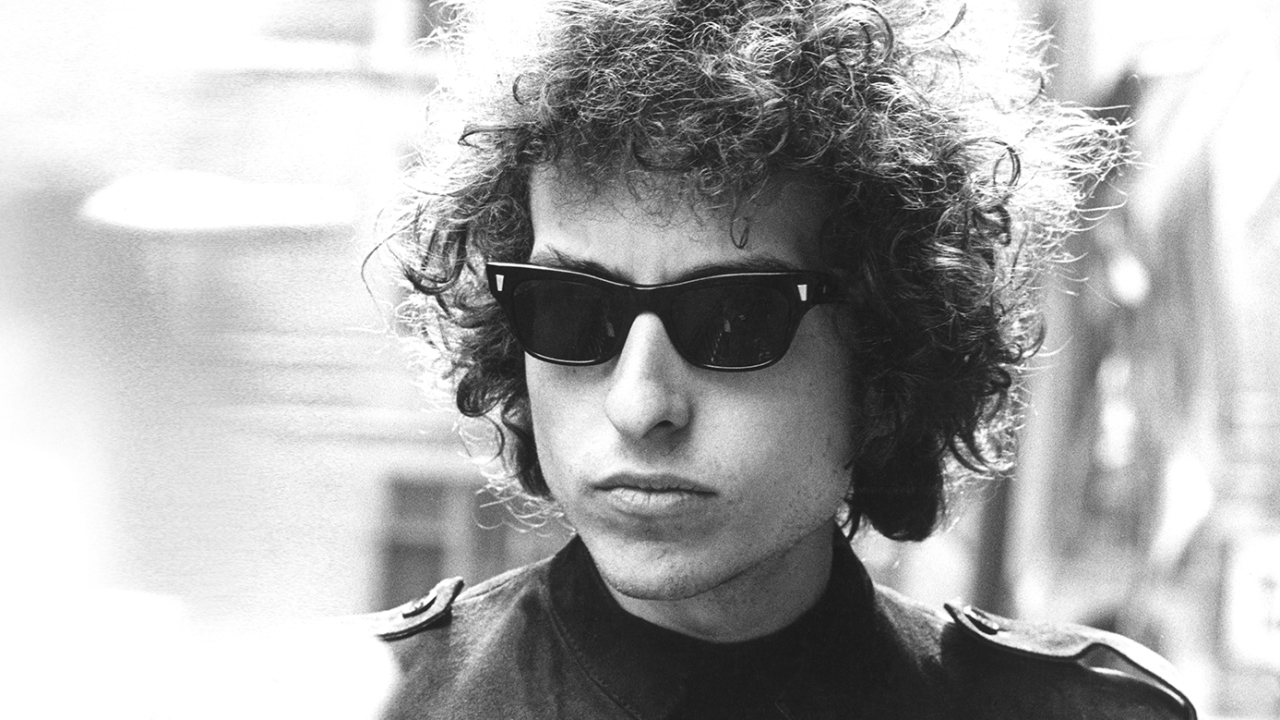

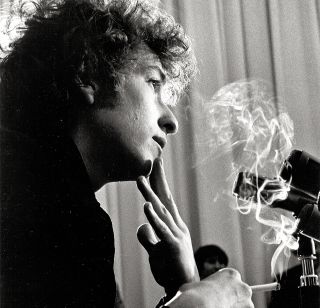

The inclusion of a book of photographs from the Holy Trinity period is not just a gratuitous extra, because Dylan’s image especially in ’65 and ’66 was essential to his creation. You couldn’t have Billy Joel or Paul Simon singing Ballad Of A Thin Man or Visions Of Johanna. The character who sang those songs had to be dark, skinny and androgynous, a doomed visionary adrift in the neon night of the city – Rimbaud on methedrine.

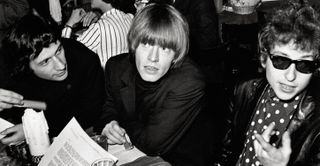

It was just such an image that Dylan assembled. His wardrobe was a code: shades (from crazy jazz saints such as Miles Davis), electroshock hair (Einstein, Chopin, Bride Of Frankenstein), high-heeled suede boots (The Beatles), black jeans (the Beats), and flashy polka-dot and ruffle fencing shirts from the Brit Invasion pantomime. By the time he got this character together he was dripping with attitude.

You can see this exotic creature in action in Don’t Look Back, DA Pennebaker’s documentary of Dylan’s 1965 UK tour, and, if you’re lucky, in Dylan and Howard Alk’s speed-freak edit of footage of Dylan’s 1966 English tour (the singer has rarely allowed this film to be screened). There’s a third film using the same footage edited by Pennebaker and Dylan’s road manager/confidante Bob Neuwirth into a relatively sane documentary called Something Is Happening.

The album’s centre, its source of energy, is the creation of the character who’s singing on the album, an amped-up fantasy image of himself, Electric Bob.

In the summer of 1965 when I first heard Like A Rolling Stone, I began to suspect there was something supernatural about Dylan. It wasn’t just the surreal lyrics, his radiating image, his gnomic answers – as if this weren’t enough. The quirky organ, the surreal stream-of-consciousness lyrics, the distorted reality it projected was clearly an occult act. It changed you in that six minutes and 13 seconds; you saw the world through his X-ray specs. You became Bob.

He’s telling you (or someone) something almost subliminally. You don’t know why, but you’re mesmerised by his tale. A tale you’re not quite sure you follow – but that’s what is so compelling about it. The cast of characters is straight out of a Fellini movie: ‘the mystery tramp… the diplomat with his Siamese cat… Napoleon in rags….’ It’s about whoever and what they did, but none of this matters.

It’s the delivery, that insinuating tone of voice, and the expressionist language he uses to paint this bizarre Bohemian underworld diorama with all these freaks in it. You’d never heard anything like it before, but you don’t need to figure anything out, there is nothing, really nothing, to figure out.

It stunned me in the middle of the day: “What was that?” His ability to convey these freakish images channelled from some shadowy zone of Dylan’s head, as if, while listening to the song, these thoughts had spontaneously occurred to him and he had telepathically transmitted them to you. “If the songs are dreamed, it’s like my voice is coming out of their dream.” He actually said that!

Like A Rolling Stone was something new and strange delivered with a laid-back hipster’s disdain. The implication was that the world doesn’t have to be the way we inherited it. On the contrary, it can be like this. Let me show you some pictures. A sense of magic transformation projected a new age of infinite possibility and oddness. You heard Like A Rolling Stone and you were in it. It was as if you’d fallen through the rabbit hole.

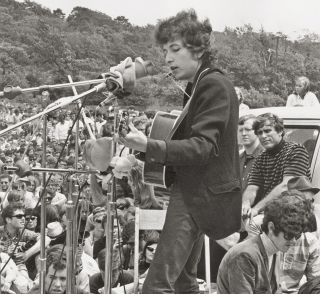

When I heard Dylan was going to perform at the Newport Folk Festival in July 1965, I had to go. I spotted him and his entourage walking into the dining room of the Viking Hotel. He looked like he’d stuck his finger in an electric socket or been struck by lightning – which seemed entirely possible, as how else could you explain such a fantastic apparition?

And with the implicit understanding that I was cool (I’d been cool for at least five days now) and that one hipster could talk to another, I asked if I could interview him. “Later,” he said. “Much later.” Then he pointed to a cute girl in a mini-skirt and said: “Check out the box on that chick.” It sounded like a meaningless and dopey thing to say but, hey, it was Bob.

Wild stories started to circulate about him. About that alleged booing: when Dylan played his Fender Strat at Newport, there may have been some grumpy folk garden gnomes booing but I didn’t hear it. I’m not saying these antiquarians weren’t mad. Dylan had pulled down the walls of Jericho. Allegedly Pete Seeger, the grand wizard of folkdom, was backstage with an axe trying to cut the electric cable.

But according to Al Kooper (who was on stage performing with Dylan) the booing was probably because he only played three songs. And we’d driven over 400 miles to get there. It had taken us seven-and-a-half hours from New York. It wasn’t so much that Dylan played electric guitar at Newport, but that he was electric in philosopher Bertrand Russell’s definition of electricity: “Not so much a thing as a way things happen.”

Mike Bloomfield, who played guitar that afternoon, thought they’d cheered. But Dylan, with his endearing perversity, loved the booing. He revelled in it, he provoked it. It fed into his rebel, outlaw image. And now it’s gone into history.

Since Dylan’s musical output was in the form of albums and the content was either pseudo-autobiographical (singing other people’s songs as if they’re your own) or outright autobiographical (mythologised versions of his own experiences), he soon realised he’d created a series of fictional characters running wild and loose and his albums were, in effect, novels.

In some ways the Bob Dylan of the mid-60s is the final flowering of beat literature. Continuing the epic tradition of Jack Kerouac’s life as an ongoing series of autobiographies, but putting it all together and in such a portable, accessible way through pop songs.

And that’s the way Like A Rolling Stone started out. Like any intense, overweening book-saturated youth, he wanted to write a novel. He did eventually – sort of – with Tarantula (written in ’65 and ’66 but not published until ’71), which failed in a more or less spectacular way. He always was a brilliant writer of liner notes. In fact his so-called autobiography, Chronicles, is actually a bunch of liner notes.

Like A Rolling Stone’s outpouring of contempt came to Dylan initially in the form of a poison prose poem, a “long piece of vomit…” It started out as a Kerouac-style rant that was, in Dylan’s words, “very vomitific in its structure… A rhythm thing on paper all about my steady hatred directed at some point that was honest. In the end it wasn’t hatred, it was telling someone something they didn’t know, telling them they were lucky. Revenge, that’s a better word.” An angry song born out of rage, which has always been a component of Dylan’s temperament.

When I got back from Newport I bought Bringing It All Back Home, which had come out the previous March. First of all let’s talk about the cover, since it has some bearing on Dylan’s image-making and mystique-mongering. It’s so strewn with pregnant symbols that it’s been compared to Van Eyck’s The Arnolfini Wedding. As opposed to his earlier incarnations, the Chaplin-esque waif or earnest Dustbowl Bob, champion of the oppressed, here’s ‘Big Hair Bob’ Dylan as a hipster dandy.

A sensuous woman in a red dress reclines on a couch languidly smoking a post-coital cigarette. Clues are scattered everywhere, and the whole scene is enclosed in a blurred halo, as if we are seeing it through a keyhole, down upon our knees. So provocative was this image and so enigmatic was Dylan that some hypothesised that the woman was Dylan in drag. It’s actually Sally Grossman, his manager’s wife.

It’s an Easter egg hunt. But we’ll leave the deciphering of the clues to seasoned Dylanologists. Let’s put the bloody record on.

Bringing It All Back Home isn’t an album in the sense of a collection of songs, it’s a revolution in attitude. Every song – even the blues yarns Outlaw Blues and On The Road Again and the burlesque Americana of Bob Dylan’s 115th Dream – comes at you with ferocious intelligence and the most intense and inventive lyrics ever heard.

The album is half-acoustic, half-electric, but Dylan doesn’t start with the acoustic tracks, the way he did in concert. The first track, Subterranean Homesick Blues, is pure high-octane rock.

Because you’re such a cool cat you recognise the title as a reference to Dylan’s idol Jack Kerouac’s book about the Bohemian underworld, and the song itself is a mutated riff on Check Berry’s rock’n’roll rant, Too Much Monkey Business. So right there you have in a nutshell what Dylan is up to: marrying modernist writing with the mojo of the blues and the raunch of rock’n’roll. As if Sonny Boy Williamson were reciting Kafka in 4/4 time while rolling a joint.

This was serious immersion in hipness. It’s punk and punchy and also an uncanny forecast of rap. This track and Maggie’s Farm are his snarling kiss-off to the protest movement. Like he said: “All my songs are protest songs.” Both were issued as singles, and Subterranean Homesick Blues crept into the US chart at No.39. Dylan’s voice itself asks: Which side are you on? He’s frequently pissed off at something or somebody, everything is broken, ecology, marriage, sundown on the unions. And we’re in the car singing right long. Wherever he goes we go.

Every line of It’s All Right Ma (I’m Only Bleeding) is neon adrenaline. A haunted landscape, a country under a spell from which we are always looking for someone to wake us up. An unsparing X-ray of American culture: all fast surface and hieroglyphics promising impossible things, dream-spinning hucksterism, Fourth Of July rhetoric, sentimentality and brutality. It was Dylan’s genius to plunge into the nightmare’s black core and resurface with an astounding litany.

Mr Tambourine Man opens the acoustic side (that’s when there were two sides to every album, and you you noticed which song opened the B-side). Dylan had tried to record it on his previous album, Another Side Of Bob Dylan, but hadn’t found its groove. It’s a song so sublime you are left dumbfounded. Maybe Rimbaud in a lyrical moment could have written it, but who knows if the little hash-eater could sing. Shortly afterwards, The Byrds made their liquid-hydrogen version, thereby inventing folk rock. Dylan always denied that it was about drugs – pot specifically. But Dylan always denied everything, didn’t he?

When Dylan became a rock star, things changed. For one thing a rock star needs a group, and once you have a cast of characters to deal with they need organising. On Bringing It All Back Home the arrangements on the rock tracks are pretty ragged. Unlike other lead singers in rock who were used to working with a group, Dylan didn’t have an intuitive sense of what and when everybody should be playing, so the musicians played full out and whenever they wanted to.

In Al Kooper’s picturesque description they were “stepping on each other’s dicks”. Because of the lack of direction on the rock tracks it’s a bit of a drunken boat; a crank-filled craft on the verge of capsising and being swallowed up by the maelstrom they’ve created, spun out of the imagination and kept afloat by sheer momentum. It’s a ghost ship, but Dylan maintains his equilibrium through these unstable songs and, as with many things in Dylan’s world, the very unsteadiness creates an addictive tension, and anyway there’s so much going on you don’t notice it. At the album’s centre, its pulsing energy, is the creation of a character who’s singing the songs.

That said, there’s nothing awkward or forced about Bringing It All Back Home’s electric components. Dylan always had that electric spark in him. Even on his folk songs he played his guitar percussively, and it’s that energising, nuclear momentum inside him that drives Maggie’s Farm, like a haywire tractor knocking over an outhouse.

When you heard Dylan had recorded Maggie’s Farm in one take, and master takes of On The Road Again, It’s Alright, Ma (I’m Only Bleeding), Gates Of Eden, Mr. Tambourine Man, It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue and If You Gotta Go, Go Now (which wouldn’t make it on to the album) all in one afternoon, you knew there was something supernatural about this guy. Where’s he from, how’d he get there?

Well, the official version is he was born Robert Zimmerman on May 24, 1941 to Abe and Beatty Zimmerman in Duluth, Minnesota, a place so cold the waves froze in mid-curl. Dylan, of course, has forged his own creation myth, claiming he was born from the grooves of a 78rpm record: “The sound of that record made me feel like I was somebody else. That I was not born to the right parents or something.”

Shortly after his birth his parents moved north to Hibbing, a mining town with the biggest man-made hole in the world. He wanted to get out of there as soon as possible. But as he got older Hibbing became a repository of great imagery and nostalgia. It was also where he first encountered different kinds of music. Late at night he could hear radio stations all across the United States playing blues, country, pop, swing, cajun, mariachi… These sounds would enrich his music and become the mysterious source of some of his odder ventures, such as the perplexing Self Portrait, Shadows In The Night and Christmas In The Heart.

He was in a rock band in high school, but when he went to college he discovered folk music, then a craze in the bohemian area of Minneapolis known as Dinkytown. Rock was considered corny and commercial, so he steeped himself in the strange old tunes, many through garbled transmissions that came down to us with fantastically bizarre lyrics. In Dinkytown he came up with his first great creation: Bob Dylan.

- Gallery: Bob Dylan and The Who play the second Isle Of Wight Festival

- Q&A: Neil Young

- Bob Dylan plays show for lone fan

- The Top 10 Best Rolling Stones Blues Songs

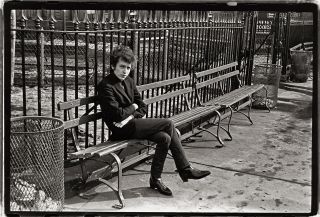

Soon afterward he discovered Woody Guthrie and made his way to New York’s Greenwich Village, a folk shtetl with coffee houses where the girls dressed in black and read weighty paperbacks. He first appeared as a Charlie Chaplin naif, his earliest songs merely imitations of Woody Guthrie’s talking blues. Like a sponge he soaked up modernist writers, avant-garde movies and left-wing politics introduced by his girlfriend Susie Rotolo.

One habit he got from Hibbing was his profound secretiveness, elusiveness and outright lying. He was a double outsider, a Jew from an obscure mining town, both of which he would deny and replace with his own handmade mythology: he was from Gallup, New Mexico, worked as a lumberjack in the great Northwest, lived with the Sioux, and so on. Writing and singing protest songs came easily to him, fired by his inner rage and resentment. He personalised radical rants by injecting modernist-word collages into his songs.

At the 1964 Newport Festival he was anointed the crown prince of folk, but this had ironically made him a star. With the exception of the folk madonnas, Joan Baez and Judy Collins, this was not an acceptable role in the folk hierarchy. In the Kettle Of Fish, New York’s prime folk watering hole, if you had a record in the charts you got a scurvy look from the old guard.

But fame and fortune were inevitable once his pop-protest song Blowin’ In The Wind was covered by Peter Paul And Mary. Although their version was criminally kitsch, it made Dylan a millionaire, and since he could no longer pretend to be part of the folk underground he decided to follow his own inclinations. He saw that writing anti-war hymns was a cul-de-sac.

Among his other talents, Dylan is the poet of rage and scathing put-downs. Even in his folk singing days his animosity could be lethal, as in Masters Of War and The Lonesome Death Of Hattie Carroll. The electric guitar not only changed the voltage of his songs, the sting of the electric guitar also matched Dylan’s outrage and sarcasm.

Shortly after Newport, Irwin Silber, the editor of Sing Out!, the righteous bulletin of the folk movement, published an open letter to Bob about how fame had changed him – warped him, in fact: “I saw at Newport you had somehow lost contact with people.” Cocooned by his entourage, his songs were now either maudlin sentiments or attacks of gratuitous cruelty. Dylan confirmed Silber’s observation by directing at him one of the most scathing put-down songs ever: Positively 4th Street, the biting words etched by Mike Bloomfield’s lethal guitar. The pain in his voice is palpable but so is the venom.

Aside from the length of his songs and his bizarre cast of characters, one of the innovations Dylan brought to pop music was new subject matter. He didn’t, at least at this point, sing silly little love songs. The vitriol of Like A Rolling Stone was followed by two more character assassinations: the one about Irwin Silber, which made it to No.7 on the US chart, and the follow-up Can You Please Crawl Out Your Window. Nobody did righteous indignation better than Bob, but with the backing of future members of The Hawks (future members of The Band minus Levon Helm) the song was too hectic and shrill and barely made it into the chart.

His next album, Highway 61 Revisited (also released in 1965), is just a straight nuclear blast of rock. Dylan has gotten the blend down, and these musicians – Al Kooper, Mike Bloomfield, drummer Bobby Gregg – perform more like a group. The propulsive momentum, especially on Highway 61 Revisited itself, with its opening slide whistle, is pure punk. On Ballad Of A Thin Man, with its Halloween music and bone-chilling lyrics, you’re just glad Bob isn’t talking about you. The album ends with Desolation Row, a reference to Kerouac’s novel Desolation Angels.

Highway 61 Revisited is blues and rock, something Dylan could do easily. He actually started out as a rock singer. Granted, Bob had told us he had been in rock’n’roll bands in high school, but by then we had become wary of taking him at his word. This was just the sort of thing he could have make up. But his teenage idols really were the piano demons Little Richard and Jerry Lee Lewis. Dylan played piano in Bobby Vee’s band under the name of Elston Gunn.

At a concert in Minnesota in 2013 that Vee attended, Dylan said that he had been on stage with everybody from Mick Jagger to Madonna “but the most meaningful person I’ve ever been on stage with” was Bobby Vee. Dylan’s first single was actually a rock song, Mixed-Up Confusion, released in December 1962.

There’s quite a bit of displaced blues poetry on Highway 61 Revisited, because that’s the highway that runs from Minnesota to New Orleans. It’s ghostly because of the blues and because it intersects with the crossroads where the Devil taught delta shaman Robert Johnson to play the blues.

But the blues on the album aren’t particularly haunted. It Takes A Lot To Laugh, It Takes A Train To Cry is a pastiche of blues lines, that would naturally involve more trains. Each verse just hangs there waiting for a song to come along. Outlaw Blues uses Southside Chicago blues to hang Dylan’s quirky nonsense lyrics on.

Dylan’s compadre Bob Neuwirth challenged him to use the line ‘when you’re lost in the rain in Juarez and its Eastertime too’ in a song, and he did just that on Just Like Tom Thumb’s Blues. There never was a weirder opening line to a song, or better advice if you ever find yourself embroiled in this noir-ish tale of misspent youth:

And your gravity fails, and negativity don’t pull you through/Don’t put on any airs, when you’re down on Rue Morgue Avenue/They got some hungry women there, and they really make a mess outta you…

Dylan was able to write baroque lyrics like ‘jewels and binoculars hang from the head of the mule…’ effortlessly, but he also caught the way people actually talked. Most pop lyrics used an artificial Tin Pan Alley diction. Dylan, on the other hand, could mimic the lope of conversation in such lines as ‘Well, anybody can be just like me, obviously/But then, now again, not too many can be like you, fortunately’ (from Absolutely Sweet Marie).

Among all these profound songs there had to be some comic relief, as in Bob Dylan’s 115th Dream, a hallucinatory cartoon of the USA as the delirious memories of a deranged Captain Ahab. And in On The Road Again he brings on stage his familiar holler-dwelling hillbilly dispensing 80-proof hokum. On Like A Rolling Stone his voice has a swirling current as he leans on the words ‘Howwww does it feeeeeel?’ with those howling vowels you can feel in your bones.

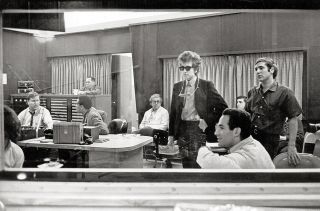

And the sound. The fusion of music and words that Dylan conjured up out of this tuning fork in his head. Anyway, he doesn’t really want to demonstrate too literally what he’s thinking. It’s better that the players follow whatever lead he gives them and that they try to approximate it. He doesn’t want the perfection of the studio musician, and to mix it up he brings in a guitar player from Chicago (Mike Bloomfield), and a guitar player (Al Kooper) to play the organ.

When people tell him Kooper’s not there to play the organ, he replies: “I’ll decide about that.” The musicians are trying to tune into Dylan’s wavelength, and the tension in that created a certain suspense in the delivery of the song. But eventually they all get contact highs. Kooper later described Dylan’s recording methods as “the road map to hell!”

Dylan’s sensitivity as to what music will work best with what lyrics is acute. On track five of the Desolation Row out-takes in the Cutting Edge box set, the musicians (Bloomfield, Kooper, Gregg and bassist Harvey Brooks) come up with a hurdy-gurdy carnival riff that would seem an ideal match for the freak-show lyrics. But in the end Dylan has a more subtle idea: he asks Nashville session guitarist Charlie McCoy to play a melody reminiscent of Marty Robbins’ El Paso. Perfect! The sweet cowboy melody doesn’t diminish the menace, instead it adds an eerie, foreboding tone to Dylan’s phantasmagoric images.

On the so-called Amphetamine Tour of 1966, Dylan and The Hawks were using up their ampage at a scary rate that was bound to burn everybody out. In the footage from that tour we see a possessed, skeletal Dylan, someone disconnected from reality, an almost spectral presence, but creating the greatest rock’n’roll music ever made.

Blonde On Blonde was recorded during the US leg of that tour. It has a sense of weariness, of things running down – ‘Lights flicker from the opposite loft… But there’s nothing, really nothing to turn off…’ This only serves to add to the mystery of the ruminative, dreamlike nature of the album, along with its heavy doses of recrimination. We see Dylan on the cover in a ghostly, out-of-focus photo as if disappearing before our eyes. Which he sort of was, as if he knew that period of his life had to end if he were to survive.

You hear that old energy surge here and there on Leopard-Skin Pill-Box Hat, I Want You and Obviously Five Believers, but Blonde On Blonde is different kind of record altogether. Dylan no longer feels the need to impress or stun the listener the way he did on the previous albums. By now he’s the undisputed Hamlet Prince of Rock. On Highway 61 he was breaking his ass. Princes don’t break their asses.

Dylan’s voice here is sweet and smooth, as opposed to the raw, Appalachian growl on Highway 61 Revisited or the raspy voice on his earlier records. Here he’s actually crooning ‘Where are you tonight, Sweet Marie?’ And unlike his characteristic manner of recording songs in one take, there are many takes of several Blonde On Blonde songs. One of the joys of the Cutting Edge box set is hearing them evolve.

Since we know the released versions, there’s a natural reflex when you hear a false start. When they start playing Stuck Inside Of Mobile With The Memphis Blues Again in 6/8 time you want to shout at Dylan: “That’s not how it goes, man!” Dylan also experiments with different genres, some quite bizarre, such as a reggae version of Visions Of Johanna and a Bo Diddley backing on Just Like A Woman. Dylan has said that on this album he got the closest to his sound – “that thin, that wild mercury sound. It’s metallic and bright gold, with whatever that conjures up.”

The true alchemy of Blonde On Blonde is the way Dylan freaks various strains of pop music in a kind of Frankenstein experiment, like patching body parts together. The oddest is his injection of pop music undertones. If you listen closely you can hear echoes of Leslie Gore, Jackie DeShannon, Carol King and The Cowsills, as well as Gershwin, Memphis Minnie, Marty Robbins, Bo Diddley, Bob Lind, Buck Owens and Ivory Joe Hunter.

There’s no better example of Dylan’s ability to communicate the actual process of thought than Visions Of Johanna, as he moves seamlessly from one scene to another through a cast of bizarre characters. We follow his voice like a stream of consciousness as images and people drift through his brain, from Louise to the nightwatchman, to the girls out on the D-train, to the Mona Lisa, the peddler, the countess, Madonna, the fiddler… Visions Of Johanna is Dylan’s most profound song, even if, or maybe because, we don’t know what’s happening. It’s an ethereal mind movie with one of the most sublime lines in rock: ‘The ghost of ’lectricity howls in the bones of her face.’

Blonde On Blonde has a claustrophobic atmosphere. Things are closing in, the oxygen is almost used up, and the mood is so subterranean you come up from it trying to avoid the bends.

Dylan’s hectic schedule came to an abrupt halt with his alleged motorcycle accident on July 29, 1966. He was said to have suffered from either a broken collar bone or three cracked vertebrae. For a while he wore a neck brace, supposedly to reinforce the ‘accident story’. But a less dramatic account has come to light which claims he was never on the motorcycle. He was wheeling it out of a garage to take it down the road and put air in the tyres, when the bike fell over onto him. And there you have the 115th theory about the motorcycle accident.

But the accident provided a good cover story for an exhausted Bob Dylan at the end of his tether. He spent a few weeks in a nearby doctor’s attic bedroom detoxing from drugs. He didn’t perform or release a new album for another two and-a-half years. When he did reappear with a new album, John Wesley Harding in December 1967, it was light years from Blonde On Blonde, a mystic, ruminating, aphoristic work.

Since Dylan was the Pied Piper of rock, John Wesley Harding’s move to a more pared-down style was taken as a cue to stop seeking after strange gods (Indian ragas, Stockhausen) and get back to your roots. The record that followed, Nashville Skyline, was an album of upbeat country songs featuring a duet with Johnny Cash. And since he was still seen as a prophet, country fever suddenly descended upon the land.

As if there weren’t enough Dylans running through people’s heads in the 1960s, the next five decades saw more incarnations. He currently seems to have settled on a variation of Vincent Price in The House Of Usher.

With other rock stars, such as Jagger, Hendrix, Elvis, Bowie even, our image of them eventually becomes stabilised. We can separate the performer from the human being. But with Dylan we’ve never quite been able to do this. As soon as you think you understand him he’s gone.

No one has written more autobiographical songs than Dylan, but in the notes for the Biograph box set he claimed that “None of my songs are autobiographical”. Well, of course he would, he’s a natural born liar and secretive as an old hen.

One thing is certain: he’s not about to write more memoirs any time soon. Even Chronicles wasn’t an autobiography. It’s actually liner notes Dylan wrote for projected Japanese reissues of As Good As I’ve Been To This World and World Gone Wrong cobbled together.

When he did tried to clear up the question about his multiphrenic identity, in an interview in 1985, things only got more confusing. “Sometimes the ‘you’ in my songs is me talking to me. Other times I can be talking to somebody else… It’s up to you to figure out who’s who. A lot of times it’s ‘you’ talking to ‘you’. The ‘I’ like in ‘I and I’ also changes. It could be an I or it could be the ‘I’ who created me. And also it could be another person who’s saying ‘I’. When I say ‘I’ right now, I don’t know who I’m talking about.”

Then again, you get some idea of how Dylan would like to be remembered. He says he admires “people who died leaving a great unsolved mess behind, who left people for ages to do nothing but speculate”.