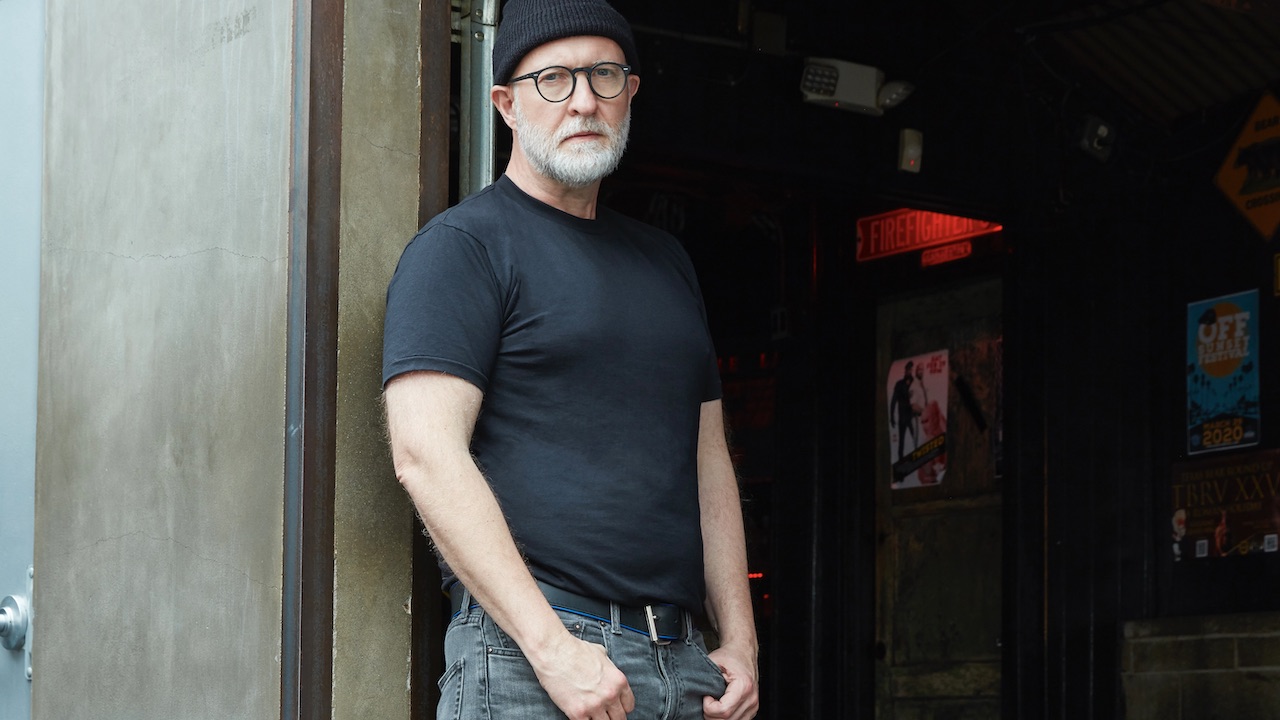

Bob Mould is a punk rock lifer, and one of the greatest songwriters ever to pick up a guitar. And as proved by 2020's brilliant Blue Hearts album, his 14th solo album, following on from his sublime work with Hüsker Dü and Sugar, his rage against bigotry, ignorance, intolerance and oppression has only increased with the passing of time. At 62, he's fully aware that the road ahead is shorter than the miles he has travelled to get to this point, but his passion for taking music to the people remains undiminished, and wholly inspiring.

"I may not leave the same amount of blood on the floor every night," he tells us from his home in San Francisco, "but I'm still happy to bleed."

So going back to the start, Hüsker Dü’s 1981 Children's Crusade tour was the first time you went on the road. When I’ve spoken before to people who were in US punk/hardcore bands during that era they’ve talked about it being a sort of ‘Wild West’ environment, and spoke about the mind blowing nature of seeing America for the first time. So I just wondered how was it for you, as a young man, to suddenly have all these new cities and new experiences opening up in front of you?

"Oh, my gosh. Well, with Hüsker Dü, you know, the band started in 1979, and our first journeys out of the Twin Cities would be to places like Madison, Wisconsin, Milwaukee, Chicago, Illinois. But yeah, the Children's Crusade was the summer of 1981, and it was quite a tour. We were based in Minneapolis, Minnesota, and the first shows, I believe, were in Calgary, Alberta, a six night engagement at the Calgarian Hotel, which was in downtown Calgary. And at the time, literally, it was the Wild West: Alberta is an oil rich province, so lots of cowboys - I don't know if that term is appropriate to use any more - but it was definitely the Wild West.

"We were playing at what, in the US, we call single room occupancy hotels, where they're maybe not proper hotels, but hotels where people are sent to live... distressed hotels, I guess. And we would be playing four sets a night, and literally running for our lives. It was just such a rough, off the streets, cowboy-ish crowd, and over the course of the week, the amount of fights, and you know, literal violence... I think the same person got stabbed at the club twice that week. So it was just like, Where are we? What is going on?

"We would play a set, and then run up the back stairs with the guitar and bass, and there would just be fights going on out in the street, there were fights in the room. Different cultural groups would be fighting, but then when the punk rock kids showed up on the weekend, these groups would all turn on the punkers. So it was like, Oh, boy, we can't win on this one! So that was the first six nights of actual touring that Hüsker Dü did."

In at the deep end!

"Right!"

The Road is a recurring motif in American culture and mythology, with that idea of escape. Was it liberating for you being in these new environments constantly, where there were no familiar eyes spying on you, and nobody checking out your business, and you could be yourself, or whoever you wanted to be, on any given night?

"Absolutely. So, to sort of set the stage, I mean, obviously, in the '80s, there was no social media, there was no internet, there were no personal computers, there were no mobile phones. So all information was traded in real time, either on landlines, or getting to know other bands and promoters, and that's how the network was built. So every day was an adventure, you know, [there was] no GPS, so you have to rely on your Rand McNally atlas, or your Auto Club atlases to get from place to place and you're spending a lot of time on payphones reaching out to make sure that the show is actually happening.

"And you're showing up in a town with no money, you're trying to find the venue, and in the punk rock scene, you're 100 per cent dependent on the generosity of others, because there's no money in this, right? Hüsker Dü was selling a seven inch single that we pressed ourselves, and if we sell a box of 20, then we'd have enough for gas money to get to the next town. Those were wild times, and it was so valuable to learn the road that way. You exchanged phone numbers with a band, and then when they came to your town, you put them up, you let them sleep at your place, you make sandwiches for them, you make breakfast or coffee for them, and off they'd go. And that's how the whole thing was built. Amazing times, and to even sort of lay that groundwork, it's sort of mind boggling in 2023."

Were there any bands or any people in particular that you felt an affinity with, that you particularly related to?

"Absolutely. I mean, on that first tour, I can go down the line: all those shows in Calgary, all the way to Vancouver, that was from having befriended and played shows in Minneapolis with a punk band called DOA. Joey [Shithead] is such a great guy, and the band was great. They had a manager, Ken Lester, and Ken knew that we were trustworthy, so he would help book those shows up from Calgary to Vancouver. And we would help DOA out in other ways in the future.

"And then we'd go down to Seattle, and there was a weekly magazine called The Rocket, and those folks used to put on shows. We would stay at The Rocket House for a week and play three shows in Seattle. And then they'd be like, 'Oh, go down on Monday [to Portland] and play with Poison Idea on New Wave Monday'. And Jello Biafra was a huge help, not only with releasing Hüsker Dü's Land Speed Record on Alternative Tentacles in Europe, but also, you know, telling us, 'Come to San Francisco, you can sleep on my back porch, and I'll get you some shows.’ So Hüsker Dü slept on Biafra's back porch for two weeks, and he got us four shows. The summer of 1981 in San Francisco was incredible. And that's where I live now, and I still go to the same Mexican restaurant now that I went to 42 years ago."

The three of us were on a mission: we thought we were the best band in the world, and we wanted to go out and prove ourselves.

Bob Mould on Hüsker Dü

Reading See A Little Light, your excellent autobiography, one band, in those days, that seemed to rub you the wrong way, or perhaps vice versa, was Minor Threat. [The two bands shared a bill in San Diego in 1983, and Ian MacKaye told Michael Azerrad "They were fucking pricks to us."] Is it all hugs and handshakes now when you see Ian?

"That was good fun. I mean, that was probably later... the thing with the aspirin [as recounted in the utterly essential Our Band Could Be Your Life, Hüsker Dü scattered aspirin pills on the stage, to tease the straight edge DC band] was in San Diego in '83. But, on that Children's Crusade tour, when Hüsker Dü wrapped up in San Francisco, we drove in one sitting from San Francisco to Chicago - which is maybe a little under 2000 miles - and I remember we got out of the van at the punk rock club, and the Necros and Minor Threat were playing. We all had just put out our first singles, and we all met and exchanged numbers. But Hüsker Dü was a hard-living bunch of guys, we drank a lot, we used drugs, and Minor Threat were totally straight edge, with the 'X' and all that stuff, and I think as time went on we sort of wound that scene up a little bit. I mean, we appreciated what they were doing, but it was it was definitely not our style. So we would poke a little bit at them, good natured, it wasn't meant to be harmful.

"But as time went on, when I lived in DC in the aughts, I would see Ian quite a bit, and Brendan Canty from Fugazi played drums with me for a couple of rounds. So all's well that ends well. But there were a lot of different scenes at the time, there was hardcore, but inside of that there was regional differences. And, you know, people were making a lot of rules sometimes for their particular scenes that maybe weren't copacetic with the way that Hüsker Dü rolled into town."

One word that struck me when reading your book was your mention of feeling “invincible” on stage back then. Was that down to the speed intake, or the alcohol, or was it just that when you were on that stage, you were this larger than life version of yourself?

"Without any of that stuff, the three of us were on a mission: we thought we were the best band in the world, and we wanted to go out and prove ourselves. We were a very physical band, a very free thinking kind of band: we were part of a tribe, but we didn't specifically adhere to all the rules of the tribe. When you add in high testosterone levels in your early 20s, and you add alcohol, and you add amphetamines, and marijuana, and in some people's cases LSD, that's a heady mix, and it's pretty... it can be volatile at times. We definitely stood up for ourselves: we were fighting for our lives. And when you add all those, you know, natural and synthetic additives… yeah, stuff happens."

At the time, you were also sort of coming to terms with your sexuality. The fact that you were shifting around constantly, was that something that helped?

"Well, when I mentioned San Francisco in the summer of '81, that was the beginning of the recognition of HIV/AIDS, as being this sort of mysterious skin cancer that was killing guys in San Francisco and other cities. And the politics of America at the time was... we had [President Ronald] Reagan who was, you know, very conservative and was following the counsel of the Moral Majority, the religious right, occult astrologers, whatever. That was a frightening time. I knew I was attracted to men, and I sort of knew what gay was, but it wasn't something that I was acting on, it wasn't something that I was leading with as a character trait: I always looked at myself as a musician who happened to be gay. So it was always music first for me in those days. I don't think I was trying to pass as straight, it's just, sort of, don't ask me about it, and I won't advertise it, and what happens happens. So that was how navigated through my 20s.

"But through that journey, especially through punk - like going to Austin, Texas, where it was a very queer-friendly punk scene, you know, that I was starting to get exposed to where queer could meet punk - I mean, I knew there were queer folk in the community, because we were all sort of outcasts. And as long as you had something to offer, or could sort of play by the general rules, you could be part of the scene. There were a lot of queer kids in it, and I got to know some, but it was pretty much keep my head down and stay focused on the task of spreading the music."

We hit the ground, sort of drunk, sort of tripping on jetlag, took a bunch of speed, got really drunk, did the show on rented gear, and then turned right around and went back to the airport

Bob Mould on Hüsker Dü's first UK show

Hüsker Dü first came to England in 1985, to play Camden Palace [now Koko], which is a 15 minutes walk from where I'm sitting. What were your memories of that first time in Europe?

"Well, that might have been... the spring of 85? [May 14, to be precise]. Hüsker Dü was on, I think, a three or four week tour of the NorthEast [US] and a fellow named Paul Boswell, who helped run SST Records in the UK, and also was a booking agent, he reached out and said, ‘Hey, I have an opportunity for you guys. If you can find a day to come over, I can get you a show at Camden Palace, but it's for this filming company, and they're going to film the entire show and fully release it.’ So we played a show in Washington, DC, and then the next day we flew from DC to London, and the next day we played the show at Camden Palace.

"So we hit the ground - sort of drunk, sort of tripping on jetlag - took a bunch of speed, got really drunk, did the show on rented gear, and then turned right around, went back to the airport, flew to Cleveland and played the next night. So I remember landing in the UK, checking into the Columbia hotel, doing the show, and then flying to Cleveland to get there about two hours before stage time!"

Okay, so you would have had no real impression of Europe from that show! What about on your first proper European tour?

"The proper European tour would have been later that year, maybe ’86. And that was amazing. We had a couple guys on our crew - our stage guy was Mick Brown, who I still work with to this day - and we piled into what we now call a sprinter and just started dashing around western Europe, spending many hours at customs dealing with carnets, and having vehicles searched. Hilarity always ensues when you are having your equipment taken apart by the Dutch immigration folks or whatever!

"And culturally, I mean, it was so different than the US at that point in time. Again, this was before the internet and before globalisation really kicked in, so the culture, the mentality, the food, the etiquette, all of it was so different. Sometimes you'd be playing squats, sometimes government facility buildings that were for elderly folks during the day, and then they turn it into a punk rock gig at night.So it was just a whole different experience. And I'm so grateful that we had that, and, that it continues to this day."

Again, talking to musicians from American bands who were touring Europe at that time there's a recurring theme of one punker at one show, who just hated America, and hated everything about America. and even though you might be an anti-establishment, anti-government American punk band, they therefore hated you too. Did you run into any of those guys on your travels?

"Um, yeah, I guess the most memorable one, and I think I mentioned it in my book, would have been in Lausanne, Switzerland. We were up on stage and really feeling some heat from the crowd for being American. It was, like, 'You coming here with your music is like Reagan in Nicaragua!' And it's like, Really? Then it sort of crossed over into physicality, and then you have to defend the stage, and then the rest of the show is really tense. But, like I said, we were three pretty strapping guys with an attitude, so if you want to bring a comment like that close to the stage, we'd be happy to help you out with it."

When Hüsker Dü ended it was an enormous loss. Because that was my entire adult identity, until that day

Obviously, Hüsker Dü came to an end, as all good things must do. Once you got back home, did you feel like that was it for you? Were you kinda burnt out and thinking you, Sod this, I'm going to go back to normality, stay at home, and put down roots?

"Well, when Hüsker Dü ended in January of 88, it was a it was an enormous loss. Because that was my entire adult identity, until that day. And then, and then it was gone. And I retreated, I went up and lived on a farm in northern Minnesota for a year and a half. And I had no idea what I was going to do. I, of course, wanted to continue on with music, but I lost that identity, and I was faced with this challenge of, Do I want to continue being that identity with a different name? Or do I want to just have my own name and identity? Which was the path that I chose, that took me to Workbook in April of '89. That year of rebuilding myself in a different way, with a different presentation that was such an important year in my life.

"And then just reemerging, and having those couple of records [Workbook and 1990's Black Sheets Of Rain] it was a challenge, because I didn't want to exist, or reemerge, using that cachet of Hüsker Dü, I was really firm about, I don't want to be billed as an ex-Hüsker Dü, just please just use my name. And I'll pay now, and hopefully, it'll pay off later, which I think it did. So then going out and touring, with the late Anton Fier [drums] and Tony Maimone [bass], who were such gifted, celebrated musicians, that was a completely different way of touring for me. With Hüsker Dü it was get in the band, sleep in the van, we drive ourselves, we do everything ourselves, to go from that DIY punk methodology to myself with two hired musicians who had different needs, whether it was higher pay, or my own hotel room every night, or dry cleaning or special dispensations, that was a bit of a challenge for me, because it was all new. And I had to trust that management was handling it right. It went as well as it could, but it was completely foreign to me."

In your book, you mention that your first solo show was at Maxwell's in New Jersey, and you talk about really nervous. Were you surprised that you ad that fear again, given that you had so many gigs under your belt by that point, and were a wiser man and an older man?

"Yeah, so Maxwell's is in Hoboken, New Jersey, and it's a club that was near and dear to my heart: Steve Fallon, who started bringing music into the club in the early '80s was a dear friend. So it was the most comfortable environment possible for me to play my first show as not Hüsker Dü, as Bob Mould. Those nerves? I mean, you know, the first Hüsker Dü shows I wasn't nervous because I was drinking so much. I stopped drinking in the summer of 86, so reemerge from my new cocoon that I have built in 1988, now I'm a solo artist in '89, I didn't know what that was going to be. So yeah, I was totally on edge, like, will people understand what I'm doing? Will it just be an evening of them yelling Hüsker Dü song titles? And that didn't happen.

"But I remember hyperventilating an hour before the show and, you know, going for the oxygen mask to try to get myself stabilised. I never had that kind of reaction before a show, ever, not for national television, not Glastonbury, not nothing, so that was new for me. So just to get that one show out of the way, it was like, Oh, okay, I think I'm doing the right thing, so I'll keep doing what I just did. And then it went well after that."

So then, the grunge revolution happened, and everyone is name checking you, particularly Nirvana, and you're held up as this sort of demigod of the underground, a real trailblazer. And then you, you come out with your new band Sugar on Creation - and the first record, Copper Blue is such a good record that everybody loves - and it seemed like people couldn't say enough nice things about you. Was that one of the first times that you could walk out onstage and everyone was on your side from moment one?

"Oh, yeah, people were very generous with their words [about Sugar]. That was an interesting time. Workbook and Black Sheets... were great records, but to come back with a power-pop record that was sort of reminiscent of where Hüsker Dü left off, but with maybe even more of the '60s pop and... I mean, Cheap Trick, the first two Cheap Trick albums were so important to me, and that informed a lot of what Copper Blue was.

Before Copper Blue came out, a few of the singles were out, and we could tell something was happening. And I think we did a record store play, and then I think we did London ULU, we walked out and within 20 seconds the place came unglued. I think part of the PA ended up in the crowd, and it was complete, total, absolute madness. And to feel that kind of involvement, and that much love and that much power from the crowd, I was like, Oh, this is really going to be something, if it keeps going like this, we're going to have a good time. And then, you know, everything just kept building for those couple, three years that Sugar was together. Alan [McGee, Creation owner] had the golden touch, the label could do no wrong, and everybody... the Primals and MBV and Swervedriver.... there was so much great music over there. There was so many great folks at Creation, and it was such a great time.

"That era, the weekly music papers had so much power - NME, Melody Maker, Sounds - that whole getting together with journalists at the pub, it was almost as if we were all writing this magnificent soap opera, with the heat between bands, you know what I'm saying. It was almost like the end of the era of rock'n'roll mythology."

Sugar was a rocket ship that went off fast, burned hard and crashed pretty quickly

And when did that cease to become fun for you?

"Well, Sugar was a rocket ship that went off fast, burned hard and crashed pretty quickly. Sugar wrapped up at the beginning of 95, and I think it was around '96, '97 - between the 'Hubcap' solo album [Bob Mould] and The Last Dog And Pony Show solo album - that I moved back to New York City and really wanted to embrace myself as an out gay man. And I looked back and saw that I had spent my entire adult life, you know, in vans, and buses and sprinters, presenting as a rock guitarist, singer/songwriter, to a primarily straight crowd. And it was important to me to try to integrate my personal identity as a gay man with the work. And that was my sort of, I'm gonna walk away from this life that I had for 19, 20 years, and I'm gonna go build this other life. So '96 through '98, things were things were starting to lead me in a different direction. I think I may I made that known to people publicly in 98, that this was going to be the last, you know, in my mind, it was going to be the last time that I was going to do what I called the dog and pony show. And when I put my bags down at the end of that tour, I thought that was it, not for performing live, but for being that that figure that I had been.

"The '90s was great. All the things that Hüsker Dü and one thousand other bands did that sort of informed what the Pixies did, that informed what Nirvana became. And when they became the biggest skyscraper, a lot of us were able to at least go to the cafeteria on the 30th floor: not all of us made it to the observation tower, but that's okay, it's great to get in the building. But by '96, I felt like that form of music was getting worn out. Once the Beatles were popular, there were 1000 imitators within six months, and this is always the history of pop music, right?"

As much as we were talking about the 'liberation' of the road, as there a sense that, when you looked back, maybe you were sort of running away from yourself?

"Um, no, I just think that with Hüsker Dü again, I was just so single minded about the music. I had a boyfriend during the band, but as for getting in the life as we used to say, into the gay world, I just never threw myself into it, and never felt like I was part of it, never built a lot of friendships or relationships with the community. So, to stop and put myself in one place for years and focus on that... I don't know if it was running away, the past was about running away. I love to travel. I love wanderlust, I'm a nomad, I love new experiences. So I don't know if I was running away, I was just running, just constantly on the go. And then to put the brakes on like that, at the beginning of '99, and just sit and build myself up as yet another new person, with a gay identity and and be part of the community, and to to get active and to give time, and give to causes to, to help build things for the community, that was that was really important to me."

So, you we talked about putting on the brakes here, and I wanted to leap ahead, if I may, to the pandemic. A lot of musicians I've spoken to since said that they had almost an existential crisis during that time, because, like you were saying about Hüsker Dü, your whole identity was built up with being a musician, and being on the road. And obviously, then for two years, or whatever, that's all stripped away from you: no-one can tour, no-one can play, no-one can share their music with other people face to face, I just wondered how that was for you?

"Oh, gosh, well, I'll set the frame and then fill in the picture. The music business I learned was you you write a record, you make a record, there's the four months in between where you set up the record, and then it comes out and you tour immediately. And that's a that's an album cycle or a campaign, and my entire life was was one campaign after the next. So in 2020, at the top of the year, I did a month of solo electric touring in the US, and I was trying out a lot of what became Blue Hearts - very political in nature, I was sort of calling back to... it reminded me of the summer of 1983, when I was writing Zen Arcade, and my government was telling me that I should die because I'm gay. It felt like I was living through all of that again. And of course it's gotten worse since I wrote that record. So that was where my headspace was, I was trying these songs out. [In] February, we three - myself and [drummer] John Wurster and [bassist] Jason Narducy - and Beau Sorensen, our engineer, you know, we hole up in Chicago and in San Francisco and made the record, got it all done, and then Boom, the whole world shut down.

"So I've got a campaign ready to go, it's on deck, and everything changed, everything stopped. I was like, Oh, my God, what are we going to do? The record was very timely, so people paid attention to it without the usual campaigning, and filibustering and touring and all that. But personally, I was like, Will I ever go back to work again? The general overarching... do we as a civilisation have enough sense to do the right thing to try to survive this? Or are we all going to die because of stupidity?"

What was the smart money on for you at that point? If you had to wager, which side were you going to, were you optimistic or pessimistic about your faith in your fellow man?

"I was on the fence, I recognised that it could go either way. The crazy irony of it is that, you know, the through line got carried by Dr. Anthony Fauci, who was so important... sort of sat on his hands a little bit, but then got very active with fighting the HIV/AIDS cause in the best way possible. And that's under Reagan, so now with Trump, Fauci there, and he's trying to fight the good fight and our our government is fighting against it. And I don't think yours was helping much at the time either...

The UK's pandemic government should all be in prison, frankly.

"Yeah, at the least. So where was I on the over/under on that one? I couldn't tell because it became so politicised. I was like, Oh my god, this is so reminiscent of the early '80s, but it just seems so vindictive and so cruel. And now with social media, you know, the gatekeepers, they lost control, and everybody was spouting so much misinformation. My now husband studied years of virology at med school, so I sort of knew what the right answer was. He and I did the best we could for ourselves and for our friends, you know, but it could have gone either way. And thank goodness, we've gotten a reprieve so to speak, on on the end of the world in terms of COVID. But, yeah, in terms of work, it broke my life. I'd paused before, but this pause was not by choice."

My party, my rules. You don't like it? Stay home.

Bob Mould on touring post-Covid

Yeah, that's the crucial difference...

"My lifeline is playing this music for people live, to express myself, and also, just to get whatever that validation is. It's important for me to go out and play to see if the message is working for people. I don't operate in a complete vacuum: I create in a vacuum, but I have to explain myself, and test my thesis, and see if it's working, so to have that part taken away was nuts.

"A lot of people ran towards Zoom, which I don't use, they were using that as a way to stay connected with their audience, and I chose not to do any of that. Because I'm really old fashioned, I really believe that music is a spiritual community experience, it's not something that translates over the computer. I mean, that's a good way to take a look at a band, and say, Oh, they look like it'd be fun, maybe I'll go see them. But that's not the way I want to convey that visceral, tactile, sensory experience. So I stayed out of all of that, and I paid a bit of a price for it, but that's okay.

"So when touring came back in the fall of 21, I was like, Oh, thank goodness, we can resume some semblance of what we do. And then we had another spike and everyone got a bit skittish. I try to be a pretty responsible person in my old age, and I know my audience is not young, and some of them are more susceptible to COVID than others, so I had to become like a crazy dictator about people wearing masks at shows. Thank goodness, 99% of the crowd complied. And we got through a month of touring with no incident. which was no small feat in October of 21."

It's crazy how being asked to wear a mask, for some people became, 'Oh, you're just a shill for the government now! I thought you were punk rock, you're not punk rock anymore!' And it's like, it's not punk rock to want you to die...

"I don't know if you've seen me perform, but there's a lot of saliva involved in my singing: when I'm onstage, within 10 minutes the amount of humidity that's coming out of my mouth, it's clearly visible under the lights. And God forbid that I would do a show, not knowing that I'm sick... the idea of going up there and exposing other people to an illness that we could easily, at least, you lessen the chances by the band testing all day and the crowd wearing masks. We could do this if we all do this everyday together. And we did. And I got a lot of blowback from people, and if it showed up on my socials, I was just like, goodbye. goodbye, goodbye. I'm not going to argue, this is a non negotiable point. My party, my rules. You don't like it? Stay home. It was very simple. Either you do it this way, or just don't come."

Yeah, it's remarkable that can people see that as some sort of infringement upon their civil liberties.

"To me we're afforded so much freedom in our lives, that the only way we can counterbalance this is to also accept all the responsibility that comes with that freedom."

To wrap this up, is there a sense now where every time that you step on the stage, there's a greater appreciation, maybe more than ever, about what you do, and that spiritual connection you talked about?

"Yes, absolutely. You know, you brought up the word 'invincible' at the top of this discussion, and I'm 62 - I'll be 63 when I roll into the UK - and the pandemic really drove home that it can all go away, instantly, for so many different reasons. So, gratitude? Yeah, it's all gratitude that I am afforded a place to speak, and a place to play, and that there's people that enjoy coming and being part of the community. It means a lot to them. Yeah, I mean, the fragile nature of things, the temporal nature of everything, it's so heightened, and so in the front of my brain every day. And, you know, as the audience gets older, it gets harder for them, our lives change. I can still be a rendition of that crazy nomadic kid, but my audience, they have families and jobs, and health issues, and I'm so aware of that. And so grateful that they take time to make an evening out of it to come and hear me do my caterwaul for 90 minutes. I know, the clock is ticking. So yeah, I may not leave the same amount of blood on the floor every night, but you know, I'm still happy to bleed."

Bob Mould's European and UK tour will call at:

Nov 13: Sint-Niklaas De Casino, Belgium

Nov 14: Oostende De Grote Post, Belgium

Nov 16: Madrid Teatro Lara, Spain

Nov 18: Granada Lemon Rock, Spain

Nov 20: Leeds Brudenell, UK

Nov 21: Edinburgh The Liquid Rooms, UK

Nov 22: Manchester Academy 3, UK

Nov 24: London The Garage, UK

Nov 25: Dublin Button Factory, Ireland