At the height of AC/DC’s Australian success in the mid-70s, before they’d cracked it in Britain, let alone America, Bon Scott was already a star in his own mind. Sitting in some pub in Sydney, a large beer and a quadruple whisky on the table before him, that gap-toothed grin on his face and a friendly female companion by his side, he would be the life and soul of the party. As his great friend and former AC/DC tour manager Ian Jeffery recalls, it didn’t matter if he’d been in the place before. “Wherever Bon went,” says Jeffery, “by the end of the night he’d have made ten new best friends.”

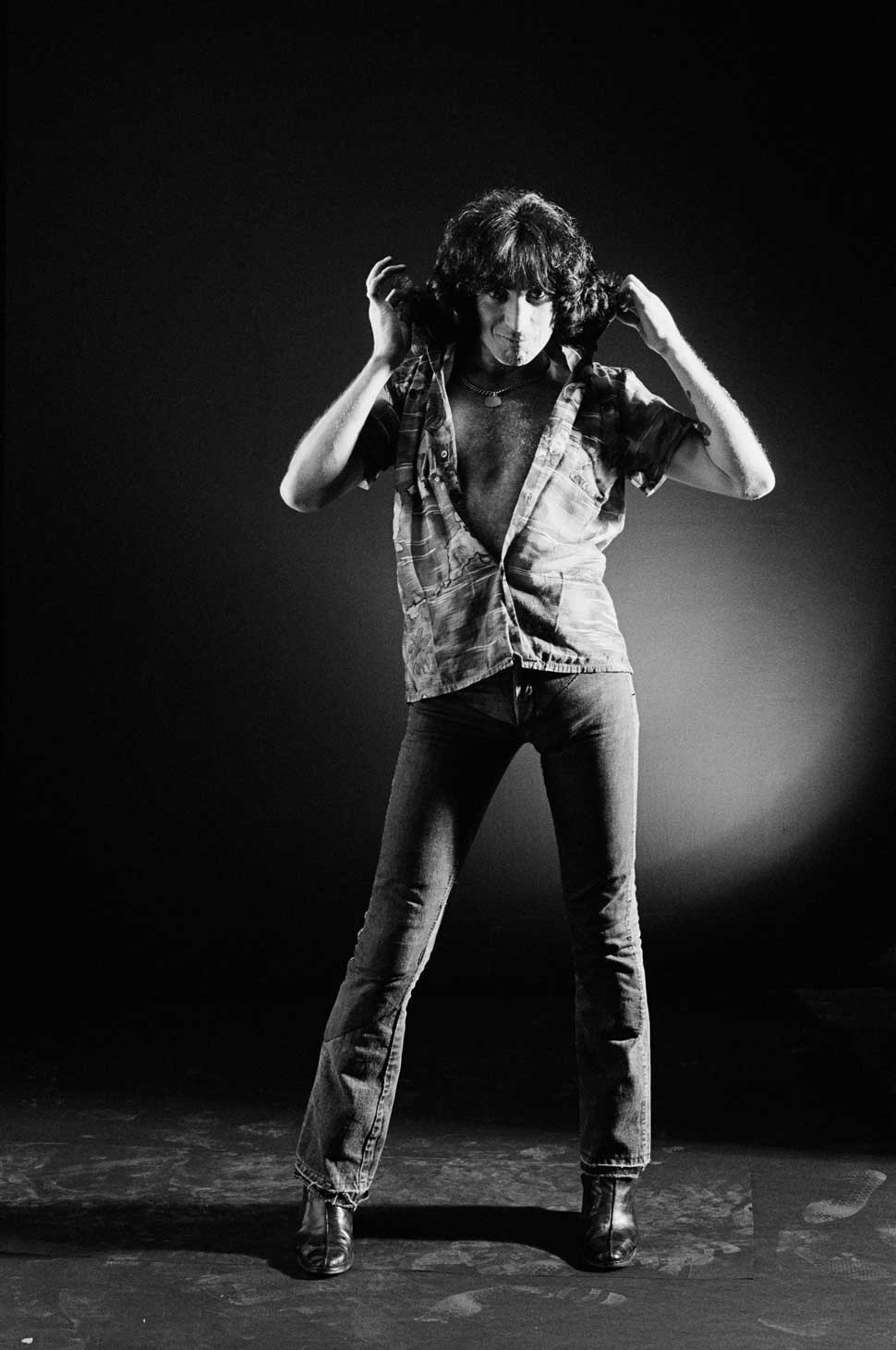

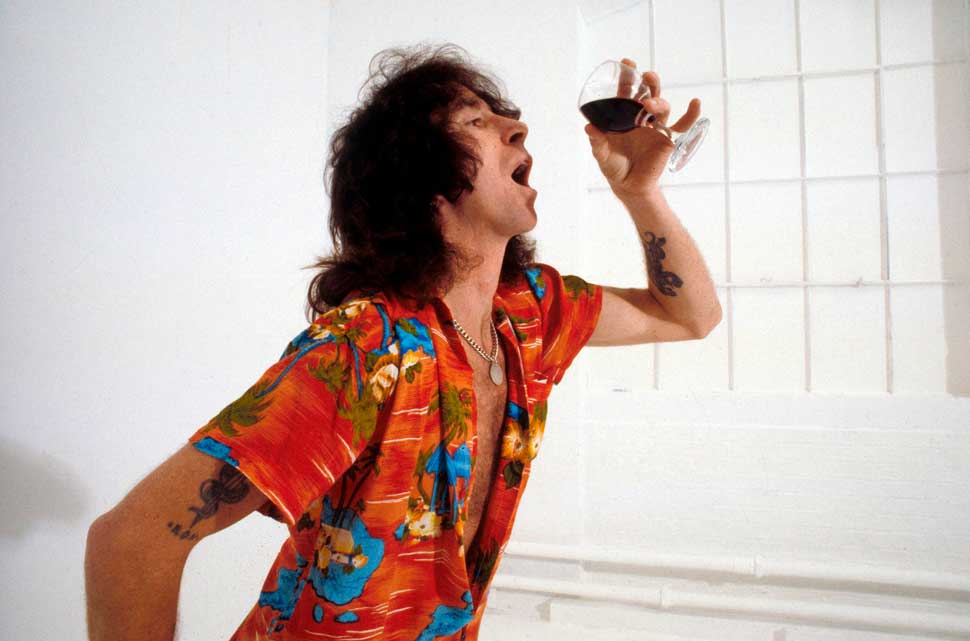

But he might just as easily have made 10 new enemies. With his wild larrikin laugh, glint in his eye and piratical tattoos festooned along his taut muscly arms, Bon was fond of a ‘blue’ – Aussie-speak for a punch-up. But only if he’d failed to charm someone first, winning them over with a brilliant one-liner. When the rough-and-tough blokes that frequented the Sydney bars where Bon liked to go would try to get a rise out of him, ask if he was AC or DC, Bon would reply: “Neither. I’m the flash in the middle.”

“Bon had that way about him,” says Jeffery, “He had the words, knew how to give them the face. And if that still didn’t work, look out!”

According to Angus Young, it was this furiously but frighteningly feisty aspect of Bon Scott’s character that moulded the best of AC/DC’s music. “He was one of the dirtiest fuckers I know,” Angus would smirk. “When I first met him he couldn’t even speak English – it was all ‘fuck’, ‘c**t’, ‘piss’, ‘shit’.”

But then the Bon Scott era of the band was far removed from the polished professionalism of the AC/DC of present day. There was nothing slick or polished about the band that Bon Scott fronted. When he sang ‘If you want blood… you got it’ he fucking meant it, pal.

But there was also another side to Bon, one that the outside world rarely got to see.

“He had a lot of the hippie ethics of the time,” says Peter Head, a bandmate and friend of Bon’s from before his time in AC/DC. “He’d read, he’d think about religion and philosophy. You could talk about serious things.”

There was also the kind-hearted guy who would – literally – give you the shirt right off his back. “He was accepting of anyone,” says his former wife, Irene Thornton, “from kids to old people. He just had a very bubbly personality and a lovely laugh, and would be very quick with a joke.”

And there was Bon the gentleman. “He was lovely to women, and women loved him,” says Fifa Riccobono, former CEO of AC/DC’s label, Albert Music. “My mum came in the office, this old Italian widow, and Bon put his arm around her. He was tattooed, tooth missing. His charm was disarming.”

But that was Bon Scott. “A great bunch of guys,” as former AC/DC manager Michael Browning ruefully puts it. “You just never quite knew which one you were gonna get – until it was too late.” He laughs, but the sadness in his voice is still there.

So what’s the true story of Bon Scott? Comedian, tragedian, entertainer, depressive, he was all of those things. He was also a prodigious drug-taker, serial womaniser, heroic drunk, poetic lyric writer. A man who loved the company of strangers yet yearned for a simpler life. A guy who helped take AC/DC to the top of the tree, yet didn’t live long enough to enjoy any of the material benefits. A sun-worshipper and a night-crawler with a body already bowed and broken long before it finally gave out on him, that cold lonely night in February 1980.

We know how the story ends, but where did it start, really? Before the mythmakers and idolaters turned it into a two-dimensional story of one clown and his many laughing followers?

Ronald Belford Scott was born in Forfar on 9 July 1946, but the fighting man was in his blood from generations past. The Scotts had been a powerful lowland clan, whose motto was ‘Amo’: ‘I Love’. They were staunch supporters of Robert the Bruce, fighting alongside him at Bannockburn. When he was excommunicated by the Pope, so were the Scotts, who were also threatened with death for following him. You want to know where Bon got his rebellious streak from, ask Robert.

The musical side came from his father, Chick. When his pipe band came marching by the house on Saturdays, little Ronnie, as his mother Isa called him, would drum along, walloping the breadboard with forks and spoons. His wanderlust was instilled early, when the family emigrated to Australia in 1952, taking advantage of the same ‘assisted passages’ that would later allow the Young family to make a new life for itself there.

Staying initially with Isa’s sister in the Melbourne suburbs, Ronnie was enrolled in primary school, where his skills as a marching drummer made him popular with the other kids. In 1956, the Scotts moved to Fremantle, near Perth. It was there that Ronnie got his nickname. Picking up on the handy congruity of his surname, little Ronnie Scott became little Bonnie Scotland. He hated it and would fight anyone who used it in the playground, but it stuck. By the time he was a teenager, even his mates called him Bonnie – or Bon, for short.

Good at athletics, but better at music, he was the under-17 marching drums champion five years running. Things changed when he discovered Chuck Berry and Little Richard as a teenager. He would sing their songs around the house, until his mother begged him to stop. “My mum used to say, ‘Ron, if you can’t sing proper songs, shut up!,” he later recalled. “Don’t sing this rock’n’roll garbage’."

Leaving school at 15, he and his first serious girlfriend, Maureen Henderson, would dress up and go rock’n’roll jiving. By now he was also a cigarette smoker and drinker, then dope smoker and speed freak. It wasn’t long before he was part of the local ‘mobs’ – street gangs of teenage hoodlums. The roughest, toughest member of the gang, Bon quickly became leader. There were various jobs – tractor driver, fisherman, apprentice mechanic. Bon didn’t care what he did for money. He knew what he was going to do with his life, he told Maureen: “Be a singer in a rock’n’roll band.”

He got his ear-pierced – unheard of for a teenage boy in the early 1960s – then went one step further and got his first tattoo: the words ‘Death Before Dishonour’. Not on his arm, though, but on his lower belly, just above his pubes. When a friend was beaten up by cops, Bon went wild and beat one of them half to death. He somehow got away with it – then got arrested stealing 12 gallons of petrol. Housed in a maximum-security facility, Bon – who would later write the early AC/DC classic Jailbreak – spent almost a year behind bars.

It was meant to be hard and it was. There were no open dormitories, only locked cells, and sexual assault was rife. Released just before Christmas 1963, Bon emerged more determined than ever to live his dream. His break came when he landed a gig drumming with covers band The Spektors. Bon decided it would be cool for the drummer to sing a couple of songs. Nobody was going to argue with the little hard nut just out of the slammer and Bon’s raucous version of The Kinks’ You Really Got Me became a highlight of the set. Bon certainly thought so.

It was at a Spektors gig that Bon met a stunning 17-year-old blonde named Maria Van Vlijman. Maria later claimed Bon asked her to marry him and that she would have let him, were it not for the fact she knew that when he wasn’t with her he was off with some other “scrag” from the gig. With Maria, though, Bon was always on his best behaviour, never swearing, never drinking.

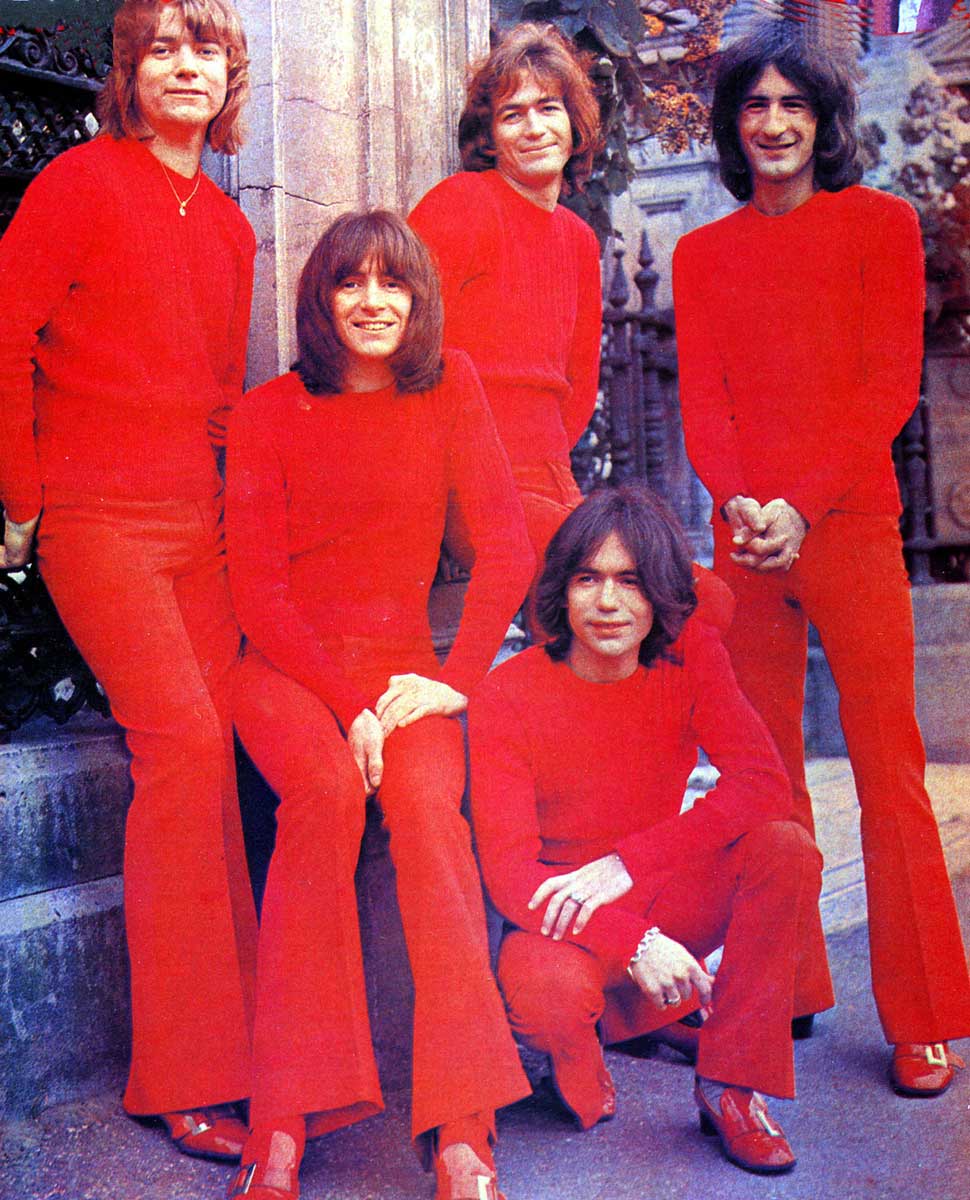

Eventually The Spektors merged with rival covers act The Winstons, fronted by singer Vince Lovegrove, to form The Valentines (above). Specialising initially in pop-soul covers, both Vince and Bon would front The Vallies, as they became known. Vince was the handsome hunk who delivered the songs straight-faced; Bon his cheeky sidekick. In their puff sleeves and colour co-ordinated suits, they would belt out Build Me Up Buttercup, Bon clutching his breast on the word ‘heart’. “We had a pretty wild stage act,” Lovegrove recalled. “We’d jump up on the amps, have firebombs going off…”

A couple of singles made it into the Western Australian charts, but it was two years before they got their national break, with their songs written for them by George Young and Harry Vanda of Aussie rock sensations The Easybeats and, later, AC/DC’s producer-mentors.

The band relocated to Melbourne, then the epicentre of the Aussie music biz. Bon wrote to Maria, who had already moved there, telling her he hoped “we can both have a good time together when I arrive” or he would be “so flippin’ lonely”. Any plans soon got buried beneath Bon’s hectic new life carousing the local nightspots. Explaining the Vallies’ appeal, Vince Lovegrove said: “I’m more popular than Bon. But he’s a far better singer than I’ll ever be. In fact, I think he’s the most under-rated singer in Australia.”

But Bon was tiring of the “cabaret act” the Vallies had become. When an old mate from the Perth scene, Billy Thorpe, showed up in Melbourne with his new rock’n’roll outfit, The Aztecs, Bon took to making unannounced appearances at their shows, belting out Whole Lotta Love and Long Tall Sally. “He was a fucking madman,” recalled Thorpe. Bon would get high and tell Billy: “You know I’m going to make it, I’m going to fucking make it.”

The Valentines were busted very publicly for possession of marijuana in 1969. When their next single – a sumptuous pop ballad written and sung by Bon entitled Juliette – was refused radio play as result, Bon became angry, bitter and disenfranchised from the whole ethos of the group. Even the normally upbeat Lovegrove threw in the towel.

Still only 23, Bon was sure there was still time for him to make his mark, so he split for the hippie hills outside Adelaide, where he intended, in the vernacular of the day, to get his head together. Except of course his head had gone long ago…

The next few years would be even more calamitous, personally and professionally, for Bon Scott, than the years that followed in AC/DC. Hooking up with another friend from the Perth scene, bassist Bruce Howe, in folk-rock outfit Fraternity, Bon grew a beard and took to playing the recorder, yearning for musical respectability.

“I got sick of doing bopper audiences with The Valentines and I wanted to become a musician, to be recognised in the Australian rock scene as more than just an arse shaker,” as he later put it.

Gordon ‘Buzz’ Bidstrup, who would later become the drummer with The Angels, met Bon during this time. “He was a long-haired recorder-playing hippie,” says Bidstrup. “He lived up in the hills, took magic mushrooms and smoked pot. I don’t remember him as being a hell-raiser, fighter guy. When I met him he was this hippie dude, as we all were. Long robes and all this stuff…”

He couldn’t keep it up. Fraternity’s keyboardist John ‘JB’ Bisset acknowledges the Bon may have become “a little Pan-like,” early on. Mostly, though, he recalls the Bon with the wicked gleam in his eye. “Bon was a great one for dispelling myths about acid culture, like the vegetarianism that many hippies embraced. I remember him wandering around chomping on a leg of roast beef at one very acid-soaked party.”

As with The Vallies, Fraternity enjoyed a couple of local hits – notably, Season Of Change, with Bon on exquisite lead vocals and moody recorder. The band decided to fly their freak flag all the way to London, taking with them wives, girlfriends, children, roadies and tour manager. Bon, who’d recently become close to a pretty blonde local girl named Irene Thornton, talked her into going with him – as his wife. The two were married on January, 24 1972, in Adelaide. The trip to London with Fraternity was to be their honeymoon.

“The first time I saw him I think I sort of grimaced a bit,” Irene says now, with a laugh. “He was bare-chested, little shorts on, no shoes, arm around a girl, drink in the other hand, weaving his way through a crowd and laughing his head off, which was a typical Bon image. I think I thought something like, you’ve got to be kidding…”

The next time they met, at a Fraternity show, Irene saw him in a different light. “He cracked a couple of jokes, and that changed my opinion of him. I made a comment about his really tight jeans – ‘What a well packed lunch!’ – and he just as quickly said, ‘Yep, two hard boiled eggs and a sausage’, and went on talking while I was killing myself laughing… I suddenly thought, he’s not really silly. And I was quite intrigued with him.”

Living in North London, money was so tight Bon took a part-time job behind the bar in a local pub. Worse still, good dope – so plentiful in the Adelaide hills – was hard to come by. Not that they were choosy. Bon was nicknamed Road Test Ronnie, as he was always the first to sample any new drugs that came their way. “He seemed able to cope with any drug that science or nature could come up with,” recalled John Bisset. The only time he came a cropper was when he ‘road-tested’ some datura, a powerful hallucinogen. “He had a bad couple of days and the rest of us avoided it.”

Things went downhill from there. Blown off opening for Status Quo, made to look outdated by the new glam threads of Slade, even a change of name and image – to Fang – failed to make a difference. They were finally put to shame opening for a modestly successful act named Geordie at Torquay Town Hall.

Bon was spellbound by the band’s singer, Brian Johnson, who’d finished the gig on his back screaming in agony (Bon didn’t know he’d burst an appendix and the agony was real). Johnson’s long-ago memories of his one and only meeting with Bon are wonderfully piquant: “Short hair, tooth missing. He was the funniest man and we had a lovely time.” Though he added: “He wasn’t half as good as he was when he joined AC/DC. They brought something out in him.”

Soon afterwards, Fraternity/Fang called it a day and returned to Australia. But before the bright new dawn came the gloom. Back home, Bon became involved with a musical collective called the Mount Lofty Rangers, fronted by Peter Head. But Bon grew impatient and began to take out his frustrations on everybody.

“Bon was almost 28, and had not reached the fame and fortune he desired,” Vince Lovegrove explained. “He felt trapped, frustrated, almost too old.”

He began fighting with Irene. Bon was in a downward spiral that finally hit rock bottom on the night of Friday, 22 February 1974. He had turned up already drunk for a Rangers session.

“He always had either a flask of red or, more often, a bottle of Jack Daniel’s on him,” says Head now. “It was pretty intense. In those days you’d drink and drive, too. He used to ride a motorbike around, and he’d be out of his head all the time.”

Not for the first time, the others got the feeling that Friday night that the problem wasn’t so much whatever Bon said it was but whatever was going on in his head. Suddenly he got into it with them. Called one a c**t. Offered to bash their brains in. Then he smashed through the door and out onto his bike again, hurling his now empty bottle of Jack onto the ground where it shattered.

Vince Lovegrove got the phone call from Irene at about 2am. She was calling from Queen Elizabeth Hospital. Bon had run his bike into an oncoming car. Now he was in a coma.

Doctors told Irene to prepare for the worst. Would she like a priest to come and give her husband the last rites? One of the nurses informed her that before he blacked out, Bon had been hallucinating, talking gibberish. “He said he’s a singer,” she told Irene, rolling her eyes.

Eighteen days later, Bon Scott was discharged from hospital. Much to his doctors’ surprise he was alive, though it would be some time before he would be able to walk unaided. His marriage was also over. Irene had had enough. Hobbling around on crutches, sleeping on Lovegrove’s couch, Bon was working as a gofer at Vince’s talent agency the first time he met the band with whom he made his legend.

Fifa Riccobono was A&R manager at Albert Music in the 1970s. She recalls seeing Bon during one his first appearances with the band. “It was his first night in Sydney with the band,” she says. “Bon was very crass, very loud and rather obnoxious, but in a funny way. The manager said, ‘Do you want to come back and meet Bon? I was prepared for a fairly rough encounter. And it was the opposite. He was charming, he picked up my hand and kissed it. He had a tooth missing and a shark’s tooth around his neck, and he looked quite menacing. But he was just gorgeous.”

The next few years have become a well-told part of the AC/DC story. How Bon replaced original vocalist Dave Evans, bringing a more earthy image to the band, as well as a staggering talent for storytelling lyrics and a marvellously characterful voice, part-Paul Rodgers, part-Artful Dodger. How AC/DC became stars at home, before setting out to conquer Britain, and, finally, after many setbacks, America, with an album, Highway To Hell, that stands as one of the greatest of all time. How it ended with Bon’s worn-out body left to die in the seat of a car belonging to someone he hardly knew.

The stories have been told but the truth has rarely been allowed out from where it’s been hiding in plain sight all these years. The often-contradictory aspects of Bon Scott’s life and personality that confused even him.

There was his extraordinary relationship with the Young brothers. Before AC/DC, says Irene, “he felt like he was an old bloke in the music world and a has-been… like it was all finished for him.” When, within weeks of joining, Malcolm ordered Bon to cut his long hair, he complied immediately. Pushing 30, amazed at being given this last chance, Bon knew where his bread was buttered. A fact he would never allow himself to forget.

It was different with the other brother. “I think the main thing Bon liked about AC/DC was Angus,” says Peter Head. “He was just knocked out by Angus. Bon was really looking for that sense of showmanship, the theatre to go with it. And so AC/DC gave him the opportunity to go a bit crazy and let that side of his personality reign a little bit.”

As the years have gone by, we have read of all the times Bon nearly missed the gig because he’d been too busy partying with yet more of those “new best friends” Ian Jeffery talks of; the times he nearly died mixing drugs and drink, most notably when two sex worker sisters in Sydney shot him up with smack and he woke up in hospital; the other times when he would boast of having all-night orgies in his hotel room.

What we heard very little of were the times, alone on the road, when Bon would ponder the choices he had made. When his brother Graeme began a relationship with Irene’s sister Faye, Bon wondered what he’d lost when he’d walked out on his own marriage. When his other brother Derek got married and had kids, he wondered what the cost was of his quest for… what? Another drink? Another woman? Was that it, really?

The closest Bon Scott ever really got to love, after Irene, was with Margaret ‘Silver’ Smith, hippie trail enchantress, heroin user and queen of the long nights. The same age as Bon, and with the same tastes for the exotic, Silver had left Adelaide and begun travelling not long after Bon had returned from London with Fraternity.

“I just set off around the world on my own and met a lot of very interesting people,” she recalled in a rare interview with 891 ABC Radio in Adelaide in February 2010. “When Bon arrived in London I’d been here for quite some time.” She claimed Ronnie Wood from the Rolling Stones “became a friend” and that they shared a house where she worked for him in an unspecified role. “So I went to a lot of really interesting gigs.”

Through my work as a PR for bands like Journey and Black Sabbath, I met both Bon and Silver in the summer of 1979 at her tiny bedsit in West London. The pair had a history, she told me. True love, as she told it, thwarted by Bon’s ambition and Silver’s refusal to be the little lady left behind at home.

With her croaky junkie voice, bleary smile and tough-cookie demeanour, Silver was no pushover. She was hard in a way so-called hard men like Bon Scott could never be. “She was part of Bon’s world,” says Michael Browning, AC/DC’s former manager, “but she certainly wasn’t part of the band’s world. She was looked upon as being a negative influence.”

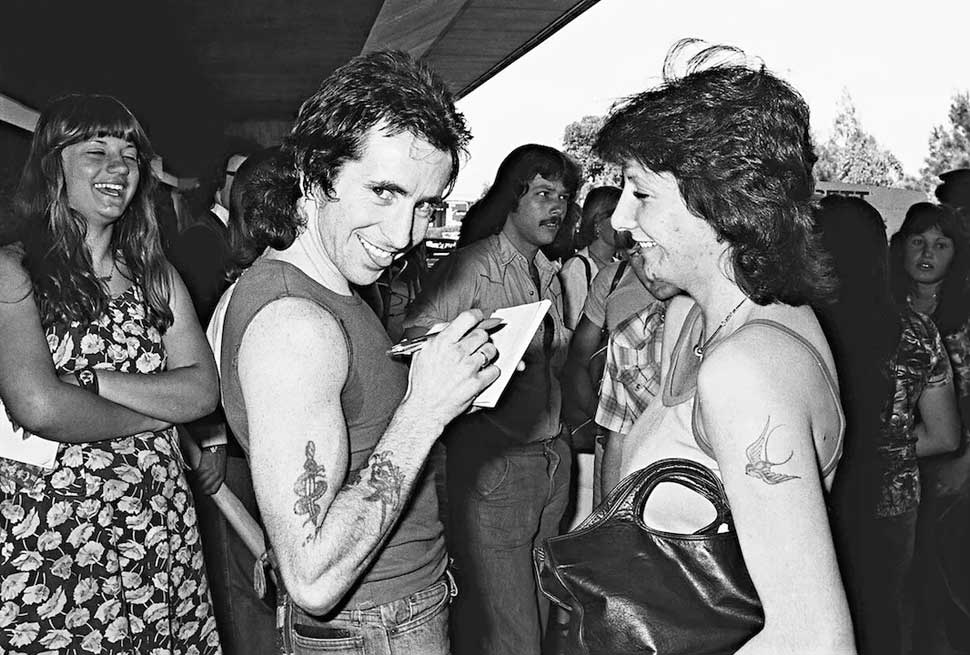

A more positive influence on the wayward singer in those final years was that of Ian Jeffery. “We would be hanging out just talking bullshit,” he says now. “Bon was a sociable guy, whereas with Malcolm and Angus it was maybe a hello or a grunt every now and again. Bon would want to have conversations, want to do different things. Bon would have friends and acquaintances all over the place. He would write hundreds and hundreds of postcards. He was always off down the post office, posting cards to people he’d met once or twice, along with people that were really good friends of his.”

For Jeffery, who would go on to work with Def Leppard, Ozzy Osbourne and U2, Bon was simply the greatest frontman there ever was. “These were the days of absolutely no technology. And most of the gigs Bon did with AC/DC, at least in America, were always opening for other big bands. So he had a job on his hands every single night and he just killed it. They would have no idea who the band was, but by the end Bon had them eating out of the palm of his hands.”

As Joe Perry told one American writer after AC/DC had just blown Aerosmith off the stage in 1979: “Bon had so many miles on him. You could tell when he sang… he was there, man.” Or as Bon himself said in 1978: “We just want to make the walls cave in and the ceiling collapse… Music is meant to be played as loudly as possible, really raw and punchy, and I’ll punch out anyone who doesn’t like it the way I do.”

The final world tour of 1979/80 found Bon Scott on the edge of the abyss, physically, mentally. For the first time, Angus, who had always looked up to Bon and loved him, began to openly fret. Malcolm, unsure whether to pull the trigger or not, chose to look the other way for now, but had decided on a reckoning when the tour was over.

“Bon was in rough shape,” their American agent Doug Thaler recalls. “He was drunk most of the time or sleeping it off. He was starting to have a real problem. The last time I saw him [was] the last date on that tour in Chicago. I saw him at the hotel in the afternoon. He was so drunk he could barely stand up. He didn’t acknowledge me. He had a couple of chicks with him, but he was in very rough shape for broad daylight. And I know the guys were starting to have problems with him by that time because of that reason.”

You get a flavour of just how worn out Bon Scott was in the film shot in Paris by French filmmakers Eric Dionysius and Eric Mistler, released a year later as the in-concert movie AC/DC: Let There Be Rock.

In it, Bon looks every one of his 33 years. And although he smiles for the camera and appears to put on a fair show for the French audience, the poses are not even ironic, merely rote, the inevitable plastic white cup full of whisky glued to his hand, his movements stiff as though in pain.

When the world tour finally ended Bon was so floored he slept for most of the 26-hour flight home, waking only to pick at the in-flight meal and guzzle as many free miniature bottles of scotch and bourbon as he could stay awake for. Back in Australia, exhausted and still drinking heavily, he spent the three-day Christmas weekend at his parents’ home in Perth. It was the first time in three years he had been home.

Like the rest of his friends, Bon’s parents Isa and Chick couldn’t help noticing how much their son’s drinking had escalated. But then New Year – Scottish Hogmanay – was always a time of drinking into the night and next morning.

Flying back to London in January 1980, Bon didn’t feel rested so much as spaced out, Sydney already seeming more like a dream. The first thing he did when he returned was arrange to finally get his own flat in London. Silver lent him a few sticks of furniture, knickknacks and kitchen utensils, to help him move in without too much hassle.

In the days before he died, Bon made phone calls to old friends and acquaintances, in some cases people he hadn’t seen for years. Among them were Michael Browning, Doug Thaler, Irene. No one says they got a sense of anything wrong.

“He always had this thing in his mind that he was never going to grow old,” says Fifa Riccobono. “I spoke to him literally days before he passed away and he was incredibly excited. He said that he’d just been with Malcolm and Angus, and he’d been listening to some of the things they’d been writing for the new album, some of the riffs. He said, ‘Fifa, wait until you hear this, it’s going to be brilliant, a fantastic album.’ In my mind, he was going in the studio three or four days later. So when I heard he’d passed away, I found it really hard to accept.”

How the greatest rock’n’roll frontman of them all died has long been the source of conjecture: too much of this, too much of that, a touch too much of everything. Ian Jeffery vividly recalls getting a phone call at 2.30 in the morning from a distraught Malcolm Young: “Bon’s fucking dead.” He remembers arriving at the hospital with the band’s new manager, Peter Mensch, at 6.30am, still unable to believe that the singer was gone, half-expecting to find Bon had somehow survived – yet again.

The Evening Standard broke the news: left in a car to sleep off a night of heavy drinking by a musician friend, Bon was found unconscious the following evening and pronounced DOS at the hospital. Police said there were no suspicious circumstances. It was this silted information that formed the backbone of every story subsequently printed around the world, and to which much of the official version of Bon Scott’s death is still attributed today. Just like his life, Bon’s death – shrouded in secrecy and rumour – would become a figment of someone else’s rock’n’roll fantasy.

Speaking in 2010, Silver Smith claimed: “He died of major organ failure… the doctor’s report said that his organs were like those of a sixty-year-old man.” But no one else I have spoken to who was there can recall any similar “doctor’s report”.

Ian Jeffery snorts with derision when I mention it to him. “If Bon had been seeing a doctor, I’d have known. I never saw any notes or prescriptions, never took him to any appointments.” In fact, according to the autopsy Bon’s liver and general health were actually in reasonable condition.

Forty years later, it hardly matters. It’s really not Bon Scott’s death we should be remembering him for, but his extraordinary life.

“It keeps you fit, the alcohol, nasty women, sweat on stage, bad food – it’s all very good for you!” Bon had proclaimed in 1979. Except of course it wasn’t. Good for the ego, maybe, no good at all for body and soul, as Bon discovered.

“I always felt that he was still out on the road after he passed away,” says Fifa Riccobono. “I still feel like he’s out on tour. I’ll see a video and I can remember exactly where we were when we did it. He’s left that legacy that you watch him on-screen and you see that grin, it’s as if he’s still there.”

The real tragedy is that, had he lived, Bon Scott might just have gone on to a better way of life. In private, stoned and tired and unable to see past the next day, he talked of “getting out”. Of maybe one more album with AC/DC and then back to Australia and a house up in the hills; a home with a wife and some “ankle-biters”.

Other times he talked of doing a solo album. Of maybe teaming up with some of the old Adelaide gang like Peter Head. In the days before his time with Peter and the Rangers turned sour, Bon and Peter had written some great stuff: the gentle Carey Gully, a sweet blend of Gram Parsons-inspired country and Celtic roots folk, based on the small town of the same name in the Adelaide Hills where Bon then lived. Its opening verse gives a wonderful glimpse of how life might have been for Bon if AC/DC had never come along, and of where he might have gone when it was over: ‘You go on down Piggy Lane through the flowers/That paint the hills as far as you can see/And that’s where I while away my hours/Hours of eternity/In a little tin shed on the hillside/Where we sit and drink our peppermint tea…’

How long that kind of peaceful feeling would have kept him happy is harder to guess. Another song he wrote with Peter, the autobiographical Been Up In The Hills Too Long, describes the frustrations of the born traveller waylaid too long by family commitments: ‘Well, I feel like an egg that ain’t been laid/I feel like a bill that ain’t been paid/I feel like a giant that ain’t been slayed/I feel like a saying that ain’t been said/Well, I don’t think things can get much worse/I feel my life is in reverse… I been up in the hills too long…’

That was Bon Scott. Too far up or too deep down. Not even he knew what was going to happen next. That’s why AC/DC loved him. And still miss him so.

This feature originally appeared in Classic Rock 212 (June 2015)