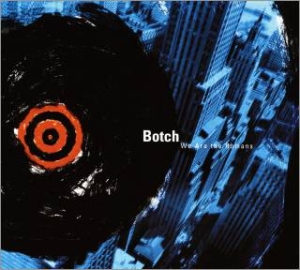

Botch: how one band redefined US hardcore and invented evil math rock

Two decades on from the release of Botch's We Are The Romans, we take a look back at the album that ripped up hardcore's rulebook and redefined America's underground scene

Released: November 1999

Length: 52:35

Label: Hydra Head

Tracklist

1. To Our Friends In The Great White North

2. Mondrian Was A Liar

3. Transitions From Persona To Object

4. Swimming The Channel Vs. Driving The Chunnel

5. C. Thomas Howell As The 'Soul Man'

6. Saint Matthew Returns To The Womb

7. Frequency Ass Bandit

8. I Wanna Be A Sex Symbol On My Own Terms

9. Man The Ramparts

10. Thank God For Worker Bees (Remix) (hidden track)

Looking back on a band or a record of significance through the telescope of hindsight can mislead your memory. It’s easy to point to War today and declare that U2 were then headed for stadiums, but right before then, around October, some felt the band were already running low on ideas. This process of reflection kind of flips with Botch, the Tacoma, Washington, band that reset the parameters of hardcore at the turn of the millennium.

Botch weren’t on the way to Red Rocks in the waning days of 1999, but in their realm they were starting to look untouchable. Right before We Are The Romans came out that November, they landed on the cover (or rather, their backs did, as the photo was of them walking away) of Seattle’s former music paper, The Rocket.

“You can’t go to a Botch show and come away unchanged” was the first thought interviewer Regan Hagar (himself a member of the bands Brad and Satchel) had to get off his chest. Their reputation was starting to precede them not just in the Pacific Northwest, but around the US and beyond.

To those in the know, Botch felt like “The future of…” just as much as the post-rock and electronica music going around in those days did. And they were…except then they weren’t…except then they were. The band imploded while word about them was still spreading, but their music and its influence hung around.

Its members quickly moved on to different bands that also helped define other corners of rock music in the 2000s: Minus The Bear in indie rock, These Arms Are Snakes in post-hardcore, Russian Circles in post-metal, and the underrated Roy in Western-edged rock. Drummer Tim Latona, whose own music background had begun with a love of jazz, stated in the oral history of the band that ran in Alternative Press in May of 2007 that they all had other sounds to explore, and explore they did. At the same time, many were only then just getting around to exploring Botch’s music.

The band’s recorded output on Hydra Head Records – especially We Are the Romans, their second and last full studio album – would come to shape what became known as metalcore in the 2000s, although their own music wasn’t called that until after the fact. In the late ‘90s, Botch were simply an intelligent hardcore band that occasionally went after famous post-Impressionists in their songs (Dali’s Praying Mantis, Mondrian Was A Liar).

When it came time to record We Are the Romans, guitarist Dave Knudson was actively avoiding some of the signature moves of both metal and hardcore. “There were hardcore cliches that we were just never gonna put into our songs,” he told Alternative Press. “I remember telling [Hydra Head founder Aaron] Turner that there wasn’t gonna be any palm-muting or open-E power chords and shit like that on our new record.”

Sign up below to get the latest from Metal Hammer, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Botch practically required a genre of their own, and in fact they came up with one. The exact moment of origin is unclear, but by the time We Are the Romans came out it was at least known among local fans that, as The Rocket pointed out, Botch were calling their music “evil math rock.” Whoever in the band came up with it, the term perfectly captured the trip Botch were on with dry, self-effacing wit.

“We liked stuff like Chavez and Don Caballero and June of ’44 and Jesus Lizard but we knew we didn’t really belong to that microcosm, even though that scene came to inspire us more than, say, Integrity or Strife or whatever bands were really carrying the hardcore torch at the time,” explained bassist Brian Cook when this writer had the chance to interview him about Botch’s history and the genres they helped define. “‘Evil math rock’ just seemed like the best way to acknowledge that stuff publicly without trying to sound like we were jumping on a bandwagon.”

Cook, Knudson, Latona and vocalist Dave Verellen had all brought different influences to their earliest practices, and pushing odd-fitting shapes into the rigid structures of hardcore created their dynamic tension. They knew from the outset that they wanted to be different, it just took them a little while to figure out how to do that.

One of the first ways this manifested was in their decision that O Fortuna from the Carmina Burana and the B-52’s Rock Lobster were equally suitable for cover versions. “The whole heavy-band-doing-ironic-covers is a really cringe-worthy concept to me now,” Cook acknowledged. “But at the time, being in a hardcore band meant covering other hardcore songs.” At some point, Cook said, “we decided that it was more interesting to find songs with dark melodies and re-imagine them with our instrumentation than to just do carbon copies of songs by our peers.”

Botch weren’t the only hardcore band feeling out this new terrain at the time. For one, there’s an obvious math reference in the title of the Dillinger Escape Plan’s debut, Calculating Infinity, which came out that same fall. All the same, ‘evil math rock’ still belongs to Botch alone. Curiously, as of the time of this writing, among the genres mentioned on the band’s fairly extensive Wikipedia page, evil math rock makes no appearance.

Math rock wasn’t even the only direction Botch were steering hardcore. We Are The Romans’ Swimming The Channel Vs. Driving The Chunnel was a (relatively) quiet breather that didn’t qualify as hardcore at all, and Man The Ramparts lumbered like When The Levee Breaks on a combo of steroids and downers. “We were trying to push hardcore forward, because that’s what all our favourite hardcore bands had done, and at that point I feel like we began to split off from the scene,” Cook said. “It’s not because we felt we were above hardcore, but it’s just that we wanted to do whatever the hell we wanted to do.”

“So we started playing more shows with bands like Death Wish Kids, State Route 522, and Behead The Prophet…bands that in my mind still qualified in some tangential way as hardcore, but were way more interesting and intense than the new straight edge bands that were cropping up at the time. Those bands turned into Murder City Devils, Sharks Keep Moving, and Tight Bros From Way Back When, which appealed to a whole new audience. All of that was really exciting and inspiring to us, and because those were our peers, it wound up that we had this foot in the door of the Northwest’s late ‘90s indie rock scene. It was a strange phenomenon, but it’s exactly what we wanted.”

Botch played a scattering of shows around Seattle and surrounding towns leading up to the release of We Are The Romans. The anticipation, the stakes, and the attendance felt higher at each one. Days before the album was set to be released they became the last band ever to take the stage at RKCNDY, one of two consequential all-ages clubs in Seattle to close that year (the Velvet Elvis being the other). Verellen introduced the set-closing Hutton’s Great Heat Engine (from their first album, American Nervoso) with a straight-faced “This is about being buried under thousands of tons of molten lava” (which it is). When the crowd repeatedly chanted the song’s penultimate line, “It’s so quiet here”, it was very much on-the-nose in the face of real concern for the survival of the city’s underage music scene.

In early 2000 they returned home from touring to find an audience that had grown in their absence. When they sold out the Breakroom on Capitol Hill in early March, there was a whisper that the club had only ever been that over-capacity once before. The stage side of the room was so densely packed that slam dancing was only voluntary toward the back.

Botch weren’t always aware that they were converting new believers at gigs like The Rocket had claimed. “I don’t know if that kind of feedback really registered with me at the time,” Cook said. “It was just the nature of the band to try and draw people in from different corners of the underground.” This continued even after the band began to succumb to a combination of writer’s block and the usual personality clashes. Their final show at the Showbox in Seattle in June of 2002 was the biggest Botch had ever headlined.

One of the major talking points in Alternative Press’ 2007 oral history was how so many bands had adopted them as an influence – or to put it less kindly, were imitating them. The thing is, this was only five years after the band had broken up. Yes, five years is an epoch for teenagers like those who were reading that article, but it really isn’t that much time in the long run. It took Botch more or less five years to get from their first practice to American Nervoso. If their chemistry had allowed them to stay together for another five or so years after Romans, who knows what might have come out of that. Though over a dozen years have passed since 2007, Botch have so far stuck to their guns about not reuniting. But we can always hope that one day they will stop sticking to those guns.

Part of the excitement around Botch as the 2000s began came from how young they still were, and how much they might still be capable of after We Are the Romans. You didn’t put Romans on and think, “These dudes have clearly peaked.” Unless you knew them personally it would be dishonest to say that in 1999 it looked like Botch were going to burn out soon. They had been playing together for six years, but had also only released two official studio albums. Those, and their final An Anthology Of Dead Ends EP, would ultimately have to stand in for the deeper discography that might have been, but it still adds up to more than enough brutal brilliance to make any heavy band formed since then envious.

Ian is the author of Appetite for Definition: An A-Z Guide to Rock Genres (Harper Perennial, 2018), and his writing can also be found at Stereogum, Under the Radar, KEXP.org and other places.