The glorious run of the original Bad Company came to an end with the release of the Rough Diamonds album in mid-1982. In later years, Paul Rodgers told the author with a laugh: “I don’t know about a diamond but it was definitely rough. The relationships had become a bit edgy, so we didn’t [even go out on] tour for it.”

As we all know, Rodgers became a solo artist before the formation of The Firm with Jimmy Page in ’84. However, Mick Ralphs and Simon Kirke, and to a lesser extent Boz Burrell, all felt that there was still some mileage in Bad Company. Although opinions between Bad Co purists and more general rock fans might possibly differ on this subject, sales figures could certainly vindicate such a suggestion.

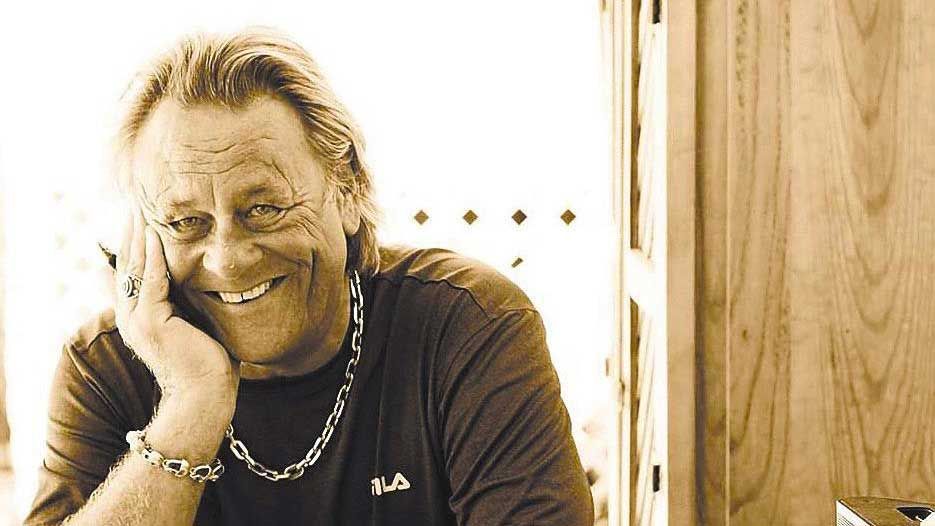

The man handed the unenviable task of following Paul Rodgers was Brian Howe, a Portsmouth-born former frontman of the New Wave Of British Heavy Metal minnows White Spirit, once the home of Iron Maiden’s Janick Gers.

Curiously, whilst he’d grown up adoring Can’t Get Enough, the swagger-infused opening track of their seminal debut album from 1974, Howe was never a dyed-in-the-wool disciple of Bad Company. He had not queued to see them play live or bought each album as it was released.

Along with a pig-headed streak a mile wide, this was probably to be his saving grace. Fiercely opposed the notion of imitating Paul Rodgers, stubbornness in the face of critics only made Howe more determined still to make the rejuvenated group a success.

“Almost without exception, everybody that I knew in the business told me, ‘Brian… Taking over from Paul Rodgers, you’ve just fucked yourself. Why would you even consider doing something like that?’” he related. “I just wouldn’t let them be right, which provided a focus and caused me to work a lot, lot harder.”

Howe had only just completed a huge world tour to promote Ted Nugent’s Penetrator album on the fateful day in 1984 when he received a call from Mick Jones of Foreigner, who was helping Ralphs and Kirke to assemble a new group. Given that it was taken at Nugent’s house, with all of those firearms around, the ensuing conversation took place in mouse-like tones.

“Mick told me that I had to get away from Ted and go to New York where Mick and Simon wanted to meet up with me,” Howe related. “So I made up some story to leave and went to the Mayflower Hotel, where we decided to give things a go.”

With the Rodgers-era ‘best-of’ Ten From Six serving as a reminder to the public of the group’s awesomeness, and Paul himself having allowed the band permission to revive the name – it’s no great secret that he did so reluctantly – it took the new-look Bad Co almost two years to craft an introductory statement.

Released in late ’86 and helmed by Keith Olson, with Mick Jones serving as executive producer and co-writer of two tracks, Fame And Fortune put them back on the map without actually bothering the Billboard Hot 100, absence of the blues-rock edge that had made the band’s name and an overuse of keyboards rendering it the product of a hairspray-clouded spell dominated by Bon Jovi, Europe et al.

“Those synths and keys… ugh,” shuddered Howe at the memory, “but Fame And Fortune certainly planted the seed of what would follow over the next few years.”

British fans received a rare sighting of Bad Co 2.0 as special guests of Deep Purple during a tour for the latter’s second post-reunion album, The House Of The Blue Light, in March ’87. This was the trek on which guitarist Ritchie Blackmore infamously refused to play an encore at London’s Wembley Arena, leaving his confused band-mates to return to the stage for Smoke On The Water without him!

Howe, who enjoyed spending a lot of down-time in the company of the Man In Black, has good memories of these dates, though being back on the road again caused Burrell, who was credited on the Fame And Fortune album but didn’t actually perform on it, to quit before their conclusion.

“After the show in Paris, two dates before we reached London, Boz put notes under everyone’s door saying, ‘That’s it, I’m outta here’,” recalled Brian. “It was kinda strange but not really unexpected.”

With Mick Jones away on holiday on the Isle Of Wight as work on the next album commenced (!), manager Bud Prager proposed the hiring of another Englishman as producer. Not to be confused with the gap-toothed comedian of the same name, Terry Thomas – a founding member of the British group Charlie – was not only an excellent producer, arriving on the project having helped to sculpt Ambition, an exquisite solo album from Styx guitarist/vocalist Tommy Shaw, but also a skilled composter in his own right. Together with Howe and/or Ralphs, Thomas stepped up to co-write the entire contents of Bad Co’s next album.

With keyboards given a heave-ho, Dangerous Age offered a fine, more commercial edge. Songs such as Shake It Up, Dirty Boy and No Smoke Without A Fire were more in line with what the doctor ordered as the album climbed to Number 58 in the Billboard chart, bringing the band Gold discs apiece.

Repeating the AOR-inclined formula only doing things better still, 1990’s Holy Water was to provide the all important breakthrough. In America, enabled by the Top 20 success of If You Needed Somebody – one of four singles lifted from the album – Bad Company returned to rock’s platinum-selling upper echelons.

“Not meaning to sound immodest but in that particular era of music, I knew exactly what Bad Company had to do in order to become successful again,” Howe claimed, “and after If You Needed Somebody blew the doors off we won over a lot of the doubters. I believe that the album has now sold more than two million copies.

“After all of our hard work the band was playing the biggest venues again,” he continued proudly. “In America the tour for Holy Water was among the biggest box office draws of 1991. It was fantastic, brilliant…”

Behind the scenes, however, things were far less ideal. Almost from day one, Howe had felt detached from Ralphs and Kirke, actually tendering his resignation to the rest of the group, manager Prager and Atco Records during the Holy Water time-frame before being persuaded to stay on.

“Going all the way back to the Deep Purple tour I never hung out with the others,” he explained. “We travelled separately because they wanted to be up all night drinking, and as the singer of the band I couldn’t do that.”

So it’s no surprise that the Here Comes Trouble album, released in mid-1992, was the vocalist’s studio swan-song with the band (a live album called What You Hear Is What You Get being the final product to bear his name).

Trouble… introduced Dave ‘Bucket’ Colwell to the line-up, a British guitarist who stayed on – temporarily, at least – in one of a number of reunion configurations. Perplexingly, it also featured Rick Wills, very recognisable as a member of Foreigner, as its bass player.

“Yeah, I can understand why that might have thrown a few people,” Brian agreed. “But it was my idea. I already knew Rick as a very upbeat, optimistic guy and the band really needed somebody like that.”

The Top 40 success of How About That, a song its co-author now dismisses as “probably a little on the light side”, confirmed that Bad Co could still carve out the hits but Howe, who at the time was “going through a horrible divorce”, had already reached the point of no return during the album’s complicated birth.

“You know what? I didn’t cross paths with anyone else from the band during the making of that record,” he revealed, emitting a laugh at the statement’s comedy value. “I worked with Terry [Thomas] and the others did their bits elsewhere without me. Then again it had been the same with Holy Water – it’s another example of crazy rock ‘n’ roll bullshit, I guess.

“Staying on [in the band] for the money was the last thing that I wanted to do,” theorised Howe of his eventual exit. “I just couldn’t do it anymore. They’d been secretly rehearsing with Steve Walsh [the singer of Kansas], so they obviously felt the same.

“Robert Hart, who eventually got the gig after I left, was a part of the London scene and already a good friend of the band. More importantly, he was also much more willing than I was to sing in a Paul Rodgers-esque style. So for them it was the perfect combination. That’s something I never understood; there is only one Paul Rodgers, so trying to cop his act… well, you’re onto a loser there, aren’t you?”

Though the relationship never lacked drama, Howe professes no regrets over his tenure in Bad Company, either as an individual or in the grander scheme of things.

“Am I proud of helping to keep the Bad Company name alive during the 1990s?” Brian mused when asked whether the good times outweigh the bad. “Of course I am. We worked our way back up to arena-headlining status… that’s one hell of achievement.”

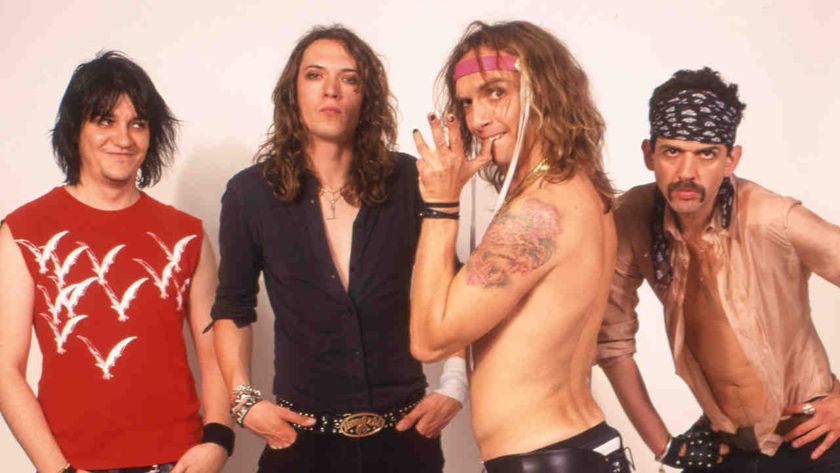

Robert Hart had already cut a cult soft rock classic album entitled Under One Sky with the rock-funk supergroup the Distance, featuring Bernard Edwards of Chic and the Powerstation’s Tony Thompson, and released a critically praised solo debut, Cries And Whispers, before accepting an offer from Ralphs and Kirke to front a revised line-up that still featured ‘Bucket’ Colwell on guitar and Rick Wills on bass.

Unveiled in the summer of 1995, the result was the eleventh studio album to bear the Bad Company name. Company Of Strangers comprised entirely of self-penned material formatted towards the group’s classic blues-inspired heyday, which was fine in principle, especially in the hands of such seasoned players, though it would be hard to deny that the results were somewhat on the generic side.

The 1995 line-up was never short on offers of live work though artistically speaking they came up wanting. Were things to continue, what the public really craved was a reunion with Paul Rodgers.

To the joy of rock music lovers worldwide, this is precisely what happened three years later when, having paid their respects together at the funeral of former manager Peter Grant, Rodgers reconvened again with the other three originals to record bonus material for a double-disc collection called The Original Bad Company Anthology.

Even better still, a short tour followed. Amazing but true: Bad Company were back! And despite the tragic passing of Boz Burrell due to a heart attack back in 2006, they have worked together on and off ever since.

A firm believer in keeping busy, Robert Hart has gigged and recorded with Colwell and Rick Wills, plus former The Small faces/The Who drummer Kenney Jones, in the Jones Gang and was installed as the singer of Manfred Mann’s Earth Band back in 2011.

He also fronts a group called Diesel that includes Jim Kirkpatrick of UK rockers FM on guitar and featured Jimmy Copley, Jeff Beck’s drummer of choice, behind the kit. A debut album followed in 2014, but Copley passed away in 2017. Hart's most recent solo album, Pure, was released in February.

When we spoke, Howe was thrilled to be working again with Terry Thomas on a new solo album – a gap of 13 years having separated 1997’s Tangled In Blue and Circus Bar in ’10 – and had hoped to persuade Ted Nugent to play some guitar on a track. “One thing’s for sure, it’ll be a rock‘n’roll record,” he predicted. The album was never released, though a song called Hot Tin Roof emerged in 2017.

And for those that didn’t pick them up first time around, Dangerous Age and Holy Water were re-packaged as a double-CD in the States in 2014, in re-mastered form and featuring bonus tracks, with a sleeve essay penned by Howe.

So long as you don’t expect Run With The Pack and Straight Shooter, it’s worthy of a listen.