“If you don’t like Bringing It All Back Home, you don’t like music. You should hand your ears back.” Bob Dylan’s game-changing album is 60 today and still astonishing

It’s not when-Dylan-went-electric, it’s not when Dylan ditched protest songs: it's when Dylan laid the foundations for everything we love

When I was a student I had a very posh and opinionated English tutor. Once we were doing Jane Austen’s Persuasion and he said, out of the blue: “If you don’t like Jane Austen, you don’t like reading.”

I laughed out loud. I hated Jane Austen and I hadn’t read Persuasion, fuck that.

Anyway: I feel the same way about Bob Dylan’s Bringing It All Back Home, which turns 60 today. If you don’t like it, you don’t like music. You should hand your ears back, check in your critical credentials, have a word with yerself.

Bringing It All Back Home is as punk as Never Mind The Bollocks, it’s as heavy as Black Sabbath (not musically, but lyrically), it is peak Americana, smarter than the nerdiest indie band. It’s a key influence on The Beatles, the Rolling Stones, The Byrds, even Led Zeppelin. It was so ahead of the curve we’re still trying to catch up, six decades later.

Think about it: In 1965, The Beatles were writing Help!, Ticket To Ride and Yesterday. They were great songwriters, sure, with hooks and melodies to spare – but they were trying to be professional Tin Pan Alley-style songwriters, the authors of love songs and standards.

They need somebody. The girl that’s driving them mad is going away. Yesterday, their troubles seemed so far away.

Dylan, meanwhile, was down in the basement, mixing up the medicine, and taking a chainsaw to Tin Pan Alley conventions. How must Lennon and McCartney have felt when they heard the words of It’s Alright Ma (I’m Only Bleeding)?

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

“While preachers preach of evil fates/Teachers teach that knowledge waits/Can lead to hundred-dollar plates/And goodness hides behind its gates/But even the President of the United States/Sometimes has to stand naked.”

Stupid, that’s how.

The Beatles met Dylan in the summer of ‘64 and – the myth goes – they turned him on to, like, electricity. Dylan passed the spliff, like “Wha-? You can plug guitars in? I’m gonna try that!” and, as a trade, helped them realise they could do better than all that yeah, yeah, yeah shit.

“I had a sort of professional songwriter's attitude to writing pop songs,” said John Lennon. “I’d have a separate songwriting John Lennon who wrote songs for the meat market, and I didn’t consider them (the lyrics or anything) to have any depth at all.

“Then I started being me about the songs… I'd started thinking about my own emotions… It was Dylan who helped me realise that.”

There’s a lot of crap talked about Bringing It All Back Home, so let’s look at that for a second. Over-worn cliche No.1: It’s the album on which Dylan INVENTED folk rock, by blending acoustic and electric music with meaningful lyrics.

Yeah, right: cos like, no-one had ever mixed acoustic and electric before. Well, apart from Chuck Berry, Little Richard, Sister Rosetta Tharpe, Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, John Lee Hooker and, ooh, probably 50-100 others.

I mean, yeah: apart from those guys, it was unheard of! No-one had done it!

Dylan’s not even the first white guy. Elvis Presley’s first single, That’s All Right – a title parodied by Dylan on It’s Alright Ma (I’m Only Bleeding) and released 11 years earlier, in 1954 – featured Elvis on acoustic and Scotty Moore on lead electric.

So Bringing is framed as being revolutionary – and it is, but not in the way it’s sometimes talked about. We are ten years or more into the rock’n’roll era by this point, nevermind the electric blues era (T-Bone Walker was releasing records in the ‘40s).

Dylan’s first pass at rock music was only startling to a folkie audience – a well-meaning but conservative bunch of nerds, by all accounts – who considered rock’n’roll an inauthentic confection at best, and cultural appropriation, at worst.

Dylan was shocking the folk audience in the same way that Elvis shocked the country audience, but no teenager listening to the blues or The Beatles (or The Stones, The Animals, The Yardbirds etc) was really going to be startled by this crazy new “beat music”.

What’s shocking and new is the voice. Not just his singing voice – it’s definitely unusual, but he is four albums in by this point. It’s the lyrical voice. Again, people like to portray this as REVOLUTION – Dylan abandoning the language of protest music for psychedelic beat poetry – but that’s not entirely accurate either.

For one, BIABH is full of protest songs and powerful, meaningful, memorable lyrics (“20 years of schoolin’/ and they put you on the day shift”) – no honest folkie could really feel cheated by the depth of the content – but, secondly, Dylan had been breaking the rules of folk songs and conjuring up symbolist beat poetry from day one.

His second album – the first one to really showcase his own material – contained A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall: “I saw a black branch with blood that kept drippin’/I saw a room full of men with their hammers a bleedin’.”

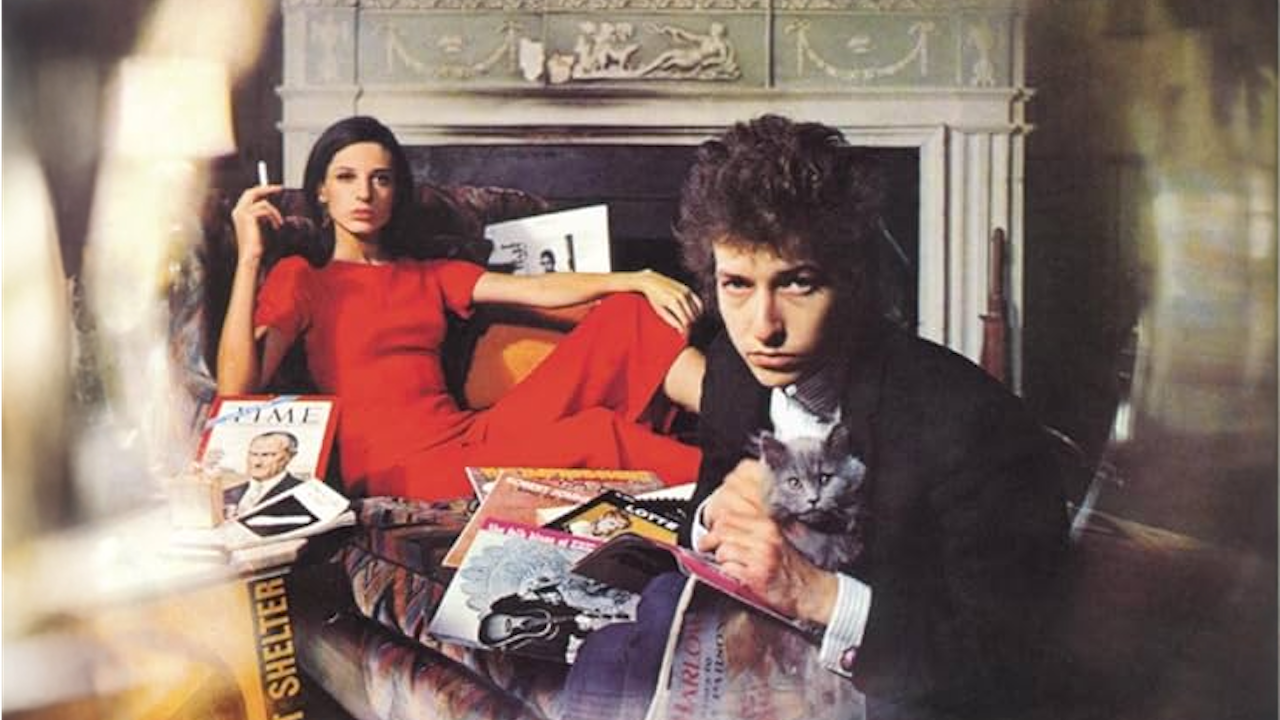

It was his thing. He was a rock’n’roll kid who learned to play like Woody Guthrie, but was born into the era of beat poetry and TV and mass media, a guy directed by Kerouac and Ginsburg (Ginsberg is literally pictured on the back cover of BIABH) to read Verlaine, Rimbaud, Baudelaire.

“I listened to the radio a lot and hung out in record stores… and learned songs from a world that didn’t exist around me,” he said.

Dylan’s own sleevenotes on the album reference bluesman Sleepy John Estes, Jayne Mansfield, Humphrey Bogart, Mortimer Snerd (a famous ventriloquist's dummy), Murph The Surf (an infamous surfer-turned-jewel thief), Allen Ginsberg, Hank Williams, Norman Mailer (“if someone thinks Norman Mailer is more important than Hank Williams, that’s fine, I have no arguments and I never drink milk”), Bach, Mozart, Tolstoy, Joe Hill (NB: not Stephen King’s son), Gertrude Stein and James Dean.

He was a cultural sponge. Where the folkies wanted to keep their music pure – and everything about that word seems suspect now – Dylan had realised that rock’n’roll was the new folk music.

Little Richard and Chuck Berry were songwriters and performers, telling stories about life today. Dylan had that too – but his vision was huge. He wasn’t interested in writing teenage anthems any more than he was in “protest songs” – he was channelling the post-war trauma, the history of America, the threat of apocalypse.

And by doing so, he elevated popular music.

He was punk: he showed a generation of singers – from Jimi Hendrix to Lou Reed, David Bowie to Joe Strummer – that they didn’t have to have an enormous range, or look like Elvis, they just had to express themselves.

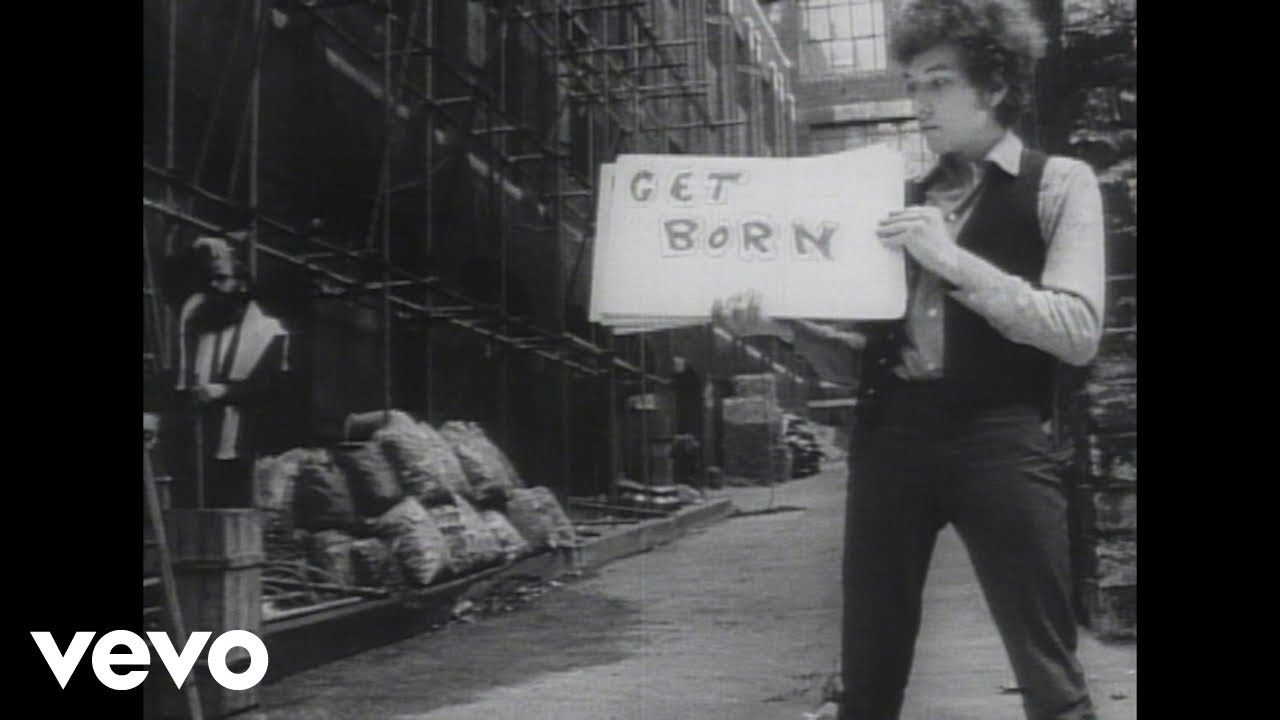

Bringing It All Back Home begins with Subterranean Homesick Blues – the title alone must’ve made the folkies shiver – the fast vocal rap of Chuck Berry on Too Much Money Business transformed into a barrage of drug paranoia (“the heat put/ Plants in the bed but/The phone’s tapped anyway/Maggie says that many say/They must bust in early May/Orders from the DA”).

Funny, hip, deep yet disposable, it comes on like an ad jingle from hell, a buncha rapped orders – “Walk on your tip toes/Don’t tie no bows” – with the kind of advice people wanted from him (“Don’t follow leaders”) comically undercut by more practical advice (“Watch the parkin’ meters”).

She Belongs Me: a beautifully melodic song of obsession. At the beginning, you’ll do anything for her, he says, but you will end up broken (“peeking through her keyhole/Down upon your knees”). The title is ironic: she belongs to no one.

I knew the phrase Maggie’s Farm before I’d ever heard the song. Maggie’s Farm had a kind of second life twenty years later when Margaret Thatcher was in power in the UK. The Specials and U2 covered it and – a protest song about bosses, drudgery, and conforming (“Well, I try my best to be just like I am/But everybody wants you to be just like them”) – it became a kind of leftist code/cliche: “We’re all working on Maggie’s farm now.”

Dylan is having the time of his life and Bob Dylan’s 115th Dream – with Spike Lee’s dad, Bill Lee, on bass – opens with him dissolving in laughter, guaranteed to get up the noses of the folkbores. Who before him has taken such delight in wordplay and shaggy dog stories? (“I got a coin to flip/It came up with tails/It rhymed with sails/So I made it back to the ship.”)

The B-Side is the “worthy acoustic side”, as though the A-side was a ruse, a tease, Outlaw Blues and On The Road Again suckering those folky fuckers into thinking he’d lost it and then

BLAM! Mr Tambourine Man: an undeniable pop hook and an ode to his own transformative powers, wherever they might take him (“I’m ready to go anywhere, I’m ready for to fade/Into my own parade”).

BANG! Cut the same day as Tambourine Man – a good day on Maggie's Farm – Gates of Eden and It’s Alright Ma (I’m Only Bleeding).

POW! It’s Alright Ma: stuffed full of astonishing images, and quotable lines:

“Flesh coloured Christs that glow in the dark/It’s easy to see without looking too far/That not much is really sacred”.

“Advertising signs that con/ You into thinking you’re the one//That can do what’s never been done/That can win what’s never been one.”

It’s a song for us working stiffs – “that must obey authority/That they do not respect in any degree/Who despise their jobs, their destinies/Speak jealously of them that are free…” – a nightmare vision that in its very creativity, by giving us those words, makes it everything seem alright.

I mean, fuck it, we’re only bleeding. It’s just a flesh wound.

It climaxes with It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue, surely a sister song to It Ain’t Me Babe, a final kiss-off to the folk scene and “protest music”. There’s enough copyists, he says, I'm moving on. Donovan, in particular, was victim to more than a few Dylan eye-rolls at this time and Bob takes extreme delight in playing this song to him in a scene in the documentary Don’t Look Back.

Donovan and co are the vagabonds at his door, dressed in the clothes that he once wore, and it’s time for him to “strike another match, go start anew.”

In the sleevenotes, he talks about being at the end of history (“the great books have been written, the great sayings have all been said") so Bringing It All Back Home takes us back to the beginning – a primordial soup of folk and blues and poetry.

The artists that followed in his wake took all the parts and built what we now know as rock music. The match had been struck. The fire was just getting started.

Scott is the Content Director of Music at Future plc, responsible for the editorial strategy of online and print brands like Louder, Classic Rock, Metal Hammer, Prog, Guitarist, Guitar World, Guitar Player, Total Guitar etc. He was Editor in Chief of Classic Rock magazine for 10 years and Editor of Total Guitar for 4 years and has contributed to The Big Issue, Esquire and more. Scott wrote chapters for two of legendary sleeve designer Storm Thorgerson's books (For The Love Of Vinyl, 2009, and Gathering Storm, 2015). He regularly appears on Classic Rock’s podcast, The 20 Million Club, and was the writer/researcher on 2017’s Mick Ronson documentary Beside Bowie.