The early 90s was a turbulent time. Just a few years after grunge turned the music scene on its head, so the sudden death of Kurt Cobain caused another seismic upheaval. With rock’s biggest bands still readjusting to this brave new world, and grunge’s superstars dazed and in mourning, rock badly needed an adrenalin shot.

Into this vacuum poured a new breed of bands: home-grown acts from provincial British towns armed with radio-friendly songs, passionate fan-bases and a shared belief that the world was theirs for the taking.

In the summer of 1994, three of these bands – Therapy?, The Wildhearts and Terrorvision – announced their arrival at the forefront of the British rock scene with show-stealing performances at Donington’s Monsters Of Rock festival. By the following summer they were joined in a resurgent rock community by bands such as Londoners Skunk Anansie, West Country rockers Reef, Northern Irish teenagers Ash and Glasgow’s Baby Chaos. Offering a noisy alternative to the mainstream Britpop scene, these disparate-sounding newcomers were banded together by the media as the ‘Britrock’ pack, the most exciting collective of raw UK talent since the NWOBHM.

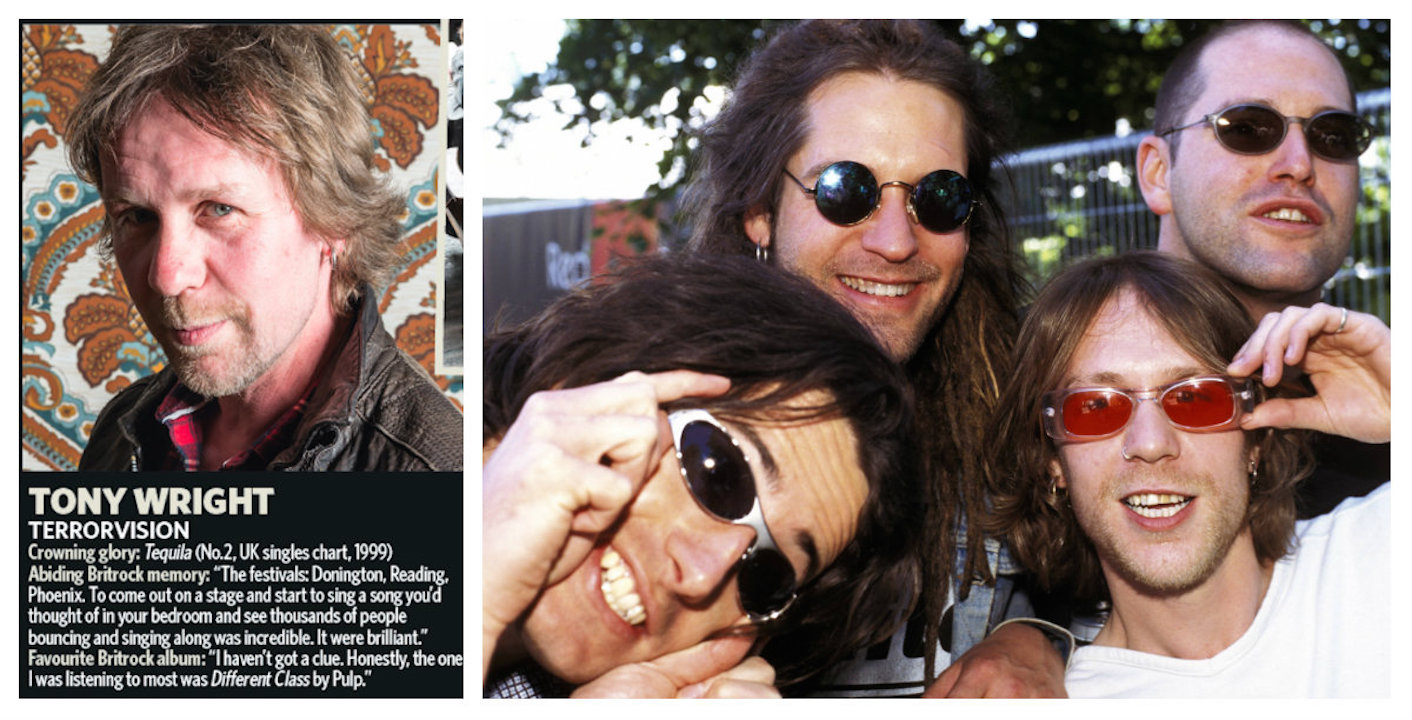

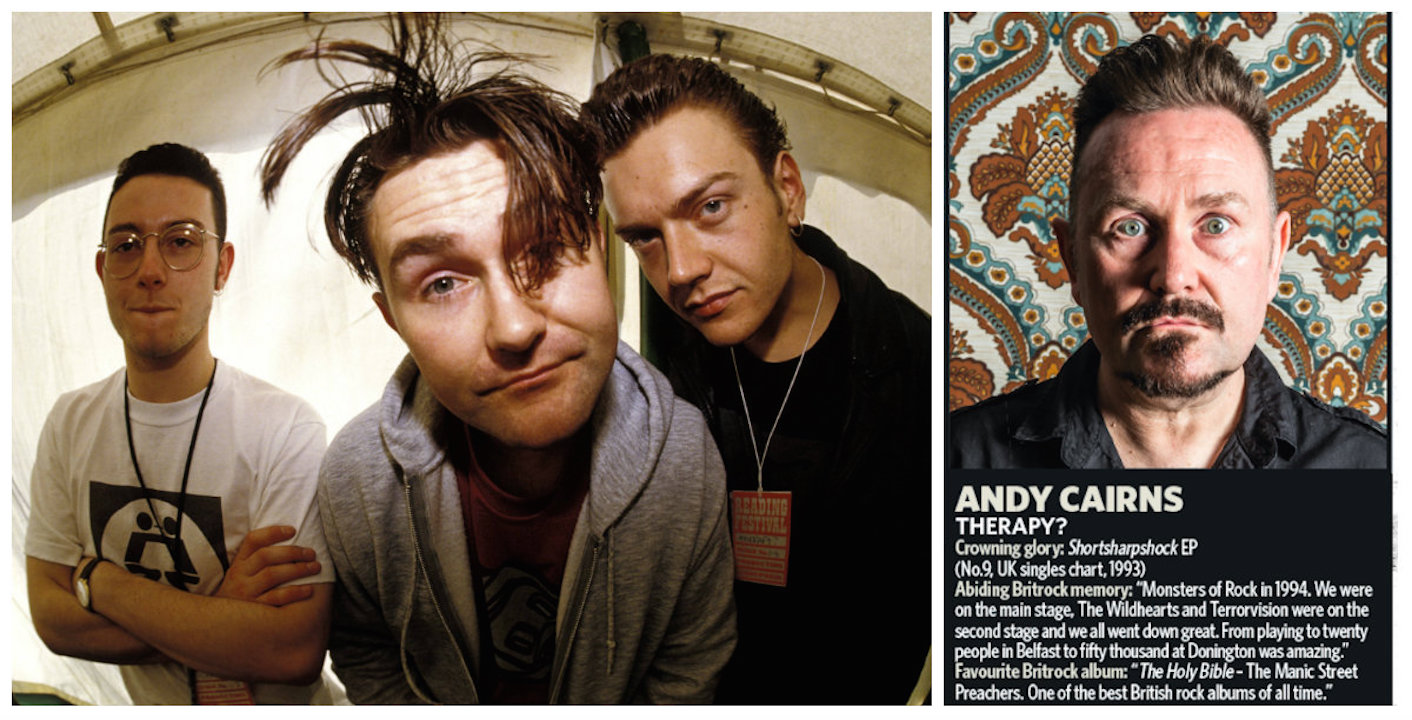

Today in a North London pub, four of Britrock’s leading lights have gathered to look back upon what was arguably the last golden age for British guitar bands. Three of them – Therapy? frontman Andy Cairns, Wildhearts guitarist Chris ‘CJ’ Jagdhar and former Terrorvision frontman Tony Wright – are still actively involved in the music business, while the fourth, former 3 Colours Red guitarist Chris McCormack, now promotes the British rock scene via club nights and the Camden Rocks music festival. They’re joined by former Radio 1 DJ and Friday Rock Show host Claire Sturgess, one of the movement’s most tireless champions.

Old friends, the five soon settle into enthusiastic reminiscing, each with fond memories of the period. “To be honest I’m just here to find out what happened,” laughs Tony Wright. “I remember getting on a tour bus in 1992, and then everything else is a blur!”

Loosely speaking, we’re now twenty years on from the birth of Britrock. When you hear the term now, what memories does it conjure up?

Andy Cairns: “Those were great years for us. We’d had our first major-label album [Nurse] in the Top 40 at the end of ’92, and in ’95 we were getting gold and silver discs and every single in the charts. We took a kind of hiatus after [1995’s] Infernal Love, but by then you had The Wildhearts and Terrorvision and 3 Colours Red starting to do amazing things.”

Tony Wright: “It were a mental time. Travelling the world, having singles in the charts… it was everything you dreamed of when you started a rock band. It made all that not listening in school really worthwhile.”

CJ: “Those years for me were equally traumatic and exciting and invigorating. Obviously the Wildhearts thing dissolved for me [Ginger fired CJ during sessions from 1995’s P.H.U.Q.]. Soon after, though, my band Honeycrack got a huge record deal and I was back in the game.”

Chris McCormack: “It was a mental time. I moved to London in ’95 with the original idea of starting a band with CJ. I lived in Camden and it seemed like there were bands drinking in every single pub. We were out every night, because there was always something going on.”

Claire Sturgess: “For me it was the most exciting time of my life. Suddenly there was this new wave of British guitar bands coming up and it felt that we owned the rock scene again. Therapy?’s Screamager was the very first track I played on Radio 1, when I sat in to do The Evening Session.”

Unlike Britpop, Britrock wasn’t a London-centric scene. But was there a sense of community among the bands?

Andy Cairns: “I think so. We toured with Terrorvision in Germany, we did shows with Honeycrack, we all knew Chris, of course. It wasn’t like we were all hanging out all the time, but there was never any bitching or back-stabbing. We were genuinely pleased to see everyone else doing well.”

Tony Wright: “When you’re in a rock band you’re too busy falling out with your bandmates to start falling out with other bands.”

During the grunge years it was fashionable for musicians to give the impression that they didn’t want to be rock stars. But with Britrock it seemed like you all had aspirations to be in the biggest band in the world.

Andy Cairns: “Therapy? came from a really underground noise-rock scene, and the music we were making in ’91 was never going to cross over to Top Of The Pops. And being from Northern Ireland, just getting heard was a challenge. We sent our first demo tape to every single record company in the UK and got only one reply, from 4AD, saying: ‘Not for us.’ But by the mid-nineties we were making music that was more attuned to a modern rock audience, and once you got on Top Of The Pops and Radio 1 it seemed like the mainstream was open to us. For working-class guys like us, we were up for taking whatever opportunities we could get.”

Tony Wright: “My granddad used to say to me: ‘If you can play an instrument, you’ll never have to buy a pint.’ He wasn’t wrong. But of course we wanted to live this to the full. Wanting to be heard is the reason you play loud and sing from the heart.”

Chris McCormack: “And people genuinely wanted to listen. We released five singles from our first album [1997’s Pure] and they all went Top 40. Bands couldn’t do that now, but it was expected then, because everyone else was charting.”

When did you all first feel your bands were properly successful?

CJ: “Getting on Top Of The Pops was such a big thing. The first time I was on it was doing Caffeine Bomb with The Wildhearts. I remember soundchecking it in front of the Mitchell Brothers and Ian Beale from EastEnders, because it was filmed at the same studio. 2 Unlimited came up to me and Danny [McCormack, ex-Wildhearts bassist] in the canteen and said: ‘You’re the puking guy!’ because they’d seen the Caffeine Bomb video. That’s fame right there.”

Tony Wright: “Top Of The Pops was an institution… and now most of the presenters are in institutions. We were on so often that I even got to present it. I remember introducing Boyzone, and saying something like: ‘Strap on your helmets and prepare to enter the Boyzone,’ and one guy giving me the filthiest look. We met Kylie, introduced Celine Dion… Surreal.”

Claire Sturgess: “There was so much music TV then. You’d have shows like Top Of The Pops that the whole household genuinely sat down to watch. Now even MTV doesn’t play music. The channels are still out there… but it’s called YouTube now.”

But Radio 1 was pretty much the only game in town for rock bands.

Claire Sturgess: “It was. And playing a new song by one of these bands was a proper event. Britpop was obviously a big scene, but it felt like Britrock was just as much of a breath of fresh air. And shows like [the indie-themed] The Evening Session supported everyone here too, so it wasn’t like the two scenes didn’t cross over. Didn’t [DJ] Jo Whiley take you to get a tattoo once, Tony?”

Tony Wright: “She used to do a thing where she’d take bands shopping, and she took us out once when we were playing in Brighton. We went to a shop called Wild Cat and it had loads of piercing jewellery, so she asked me if I’d ever get a piercing done. Joking I said: ‘I’d get my nipples pierced if they did piercings here.’ And the guy behind the counter goes: ‘Actually, we’ve just started doing piercings.’ I ended up getting both nipples done, coming out of the shop in agony, with blood streaming down my chest.”

What other surreal situations did success throw you into?

CJ: “I think I’ve blanked out a lot of the nineties, because I was doing so much weed back then. I remember doing The Big Breakfast with [alien puppets] Zig and Zag, and one of the runners coming to get me and looking at me like, God, you’re off your face and it’s half-six in the morning. Then I remember being in the toilets and this girl walked in, pulled her skirt up and had a pee next to me. It was Lily Savage.”

Tony Wright: “The best thing about doing The Big Breakfast was that it was on so early that you’d just stay up from the night before, so it had this manic atmosphere because everyone was off their heads. That was a fun show.”

Chris McCormack: “I remember doing a bungee jump for a magazine when we played Finsbury Park with the Sex Pistols, and I was off my head on E. My face turned purple for about nine hours. Johnny Rotten walked by and went: ‘Fucking hell! What happened to you?’”

Was there much rivalry with the Britpop crowd?

Andy Cairns: “We’d bump into one another, but there was no real rivalry. I remember reviewing the singles for NME, and it was me, Noel from Oasis, Justine from Elastica and Jarvis Cocker. We all got absolutely plastered and I took loads of pictures of us with my Polaroid camera. If someone who’s never heard of Therapy? comes into our house now I can pull out those photos to show we were there.”

Chris McCormack: “Our label, Creation, was all about Oasis and Primal Scream and the Britpop scene, so we’d always be around Liam and Noel and that world. I lived in Camden, and that’s where the label was based, so we dropped right into the middle of it. The whole vibe was fantastic. There was no real separation, everyone got on together. But a lot of heroin came into that scene, and things got pretty dark for some people, not least my own brother.”

Andy Cairns: “We were always friends with people like the Manics and Ash who had feet in both camps. You’d get some of the indie pop people looking at the rock bands like we were all working-class thicko knob-heads who drank lager, while they were Baudelairean libertines doing heroin in utopia, but in reality those bands were just fuck-ups in really badly cut mod suits.”

Britrock did feel like a new beginning for rock music though – a break from those old clichés.

Andy Cairns: “We were kinda the first generation of British rockers that didn’t have long hair. To be in the rock mags and not have hair down to your waist got you looked at with suspicion. I remember people writing into Kerrang! and Metal Hammer saying: ‘What the fuck are you doing putting these Paddy short-haired c**ts in this magazine?’ It was a big fucking deal initially. At the start I think people were a bit suspect of Britrock, until they started hearing the music.”

Claire: “I remember that clearly. On the Rock Show we were introducing these new bands gradually alongside the Maidens and Zeppelins and Metallicas, and there were question marks over that transition. Things were changing, and we wanted to own our own world: this was our time, time to do something fresh. Britrock was our gang.”

Tony Wright: “When we signed to EMI they said: ‘You can have whatever you want.’ And we said: ‘Okay, well then we don’t want to be on EMI.’ We meant that we didn’t want to be associated with all the slightly dodgy, run-of-the-mill metal bands they had. So they gave us our own label. We loved Kiss and AC/DC and Motörhead, but we liked Elton John and David Bowie and The Carpenters too. Our generation inherited some good record collections. But it was time for something new.”

With the notable exception of Skin in Skunk Anansie, Britrock was predominantly made up of white guys with guitars. Was that something that struck anyone at the time?

Claire: “Well, as a girl at the time – and being a girl still! – I never felt like that was an issue. I never felt unrepresented in the world of Britrock. Certainly there were a lot of girls in the fan-bases, and it always felt like girls never got excluded. If you look at these guys and their bands, it wasn’t a macho scene at all, was it?”

Tony Wright: “It was about everyone going out and having a good time, wasn’t it? Rock music should be about having the freedom to be yourself. And there was certainly no agenda to exclude anybody. Rock music has always been a bit of a boys’ club, but we wanted to make everyone dance.”

By the end of the nineties the Britrock scene had run out of steam. Did you see it coming?

Andy Cairns: “I remember sitting in Metropolis Studios in 1996 with Chris, James Manic and Ricky from The Almighty, and we were all going to go out on the tear after listening to some mixes. Chris Sheldon, our producer, said: ‘Tell the taxi driver not to crash. Because if it does, Britrock is over.’ We’re lucky it lasted as long as it did.”

Tony Wright: “We got dropped after our biggest song, which was kinda ironic. I remember being on Radio 1 after Tequila became a hit, and I was asked why I thought the song had done so well. I said: ‘Because it sounds like the kind of crap you play on the radio now.’ We had so many better songs, but people didn’t want to hear them. We’d lived in each other’s pockets for ten years, and had the best time, but nothing lasts forever.”

Chris McCormack: “When things come to an end you’re kinda at a loss as to what to do. Things were going amazing for us in 1999, and then Pete [Vuckovic, 3CR singer] wanted to go solo, and it went a bit shit at the end. I didn’t know he was going to be an arsehole.”

CJ: “But we were young then, and you dust yourself down and get on with something new. Even if Honeycrack didn’t make it, everything I did then helped me get to where I am now. If I could go back to that time now, I’d tell myself that in twenty years’ time I’d be in a much better place spiritually and emotionally, so fuck it, have a laugh and have another line.”

Andy Cairns: “I was listening to Radio 4 recently and they were talking about the Malcolm Gladwell book Outliers. They worked out that any musician’s chances of being in a successful band were 250,000 to one. So all of us around this table have beaten those odds. As an older, wiser man I can look back and think it was an incredible time, and be grateful to have been part of it. Our band is still out there, still bringing in new fans. But, honestly, if it all ended tomorrow I’d still be made up with everything we achieved.”

Claire Sturgess: “I don’t think anyone should underestimate what these guys achieved. Their records changed lives, and they’re continuing to do what they’re passionate about. If any band comes along now and has a fraction of the success and fun these guys had in the nineties, they’ll consider themselves very lucky.”