Perhaps more than any other living artist, Bruce Springsteen is America. From his first steps as a New Jersey scrapper, he was already taking the nation’s pulse, naturally drawn to the grit beneath the gloss, operating in his long-standing milieu of blue-collar towns and last-chance dreamers.

More remarkably, from the mid-’80s onwards, as a stone-cold superstar, Springsteen never lost his street-level observational smarts and righteous ire, his music speaking truth to power and demanding something more. Back in ’75, he told us he was born to run, and almost half a century later, his 21-album catalogue is the proof.

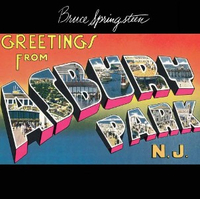

Greetings From Asbury Park, N.J. (1973)

Having convinced his Columbia paymasters to ditch their vision of a solo folk star and let him blow the house down with a pre-E Street Band, the Boss came tearing out of the blocks on this ramshackle debut.

Greetings was tracked dirt-cheap in three weeks at 914 Studios – with Springsteen breaking off to bang the waitress at the local Greek diner – and you can tell, with these “twisted autobiographies” racing by like a flickerbook of the bandleader’s childhood.

When label boss Clive Davis threw Greetings back at him (“no hits”), the Boss returned a day later with the sublime, light-footed opener Blinded By The Light – and it was off to the races.

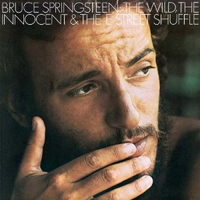

The Wild, The Innocent & The E Street Shuffle (1973)

Recorded around the clock – “towards the end of the mixing process, I’d been up for three days without stimulants” – Springsteen’s second (and superior) album of ’73 was precision-tooled with material to make him indelible to audiences during his bread-and-butter support slots.

Many of these long-form songs were modelled on a classic soul revue – always one more chorus, one more go around – while with the jangle-soul of Rosalita (Come Out Tonight), he had his first setlist perennial, and an early draft of Born To Run’s escapist tropes. Not that it stopped the label deeming the album “unreleasable”, and telling radio stations to strike it from their playlists.

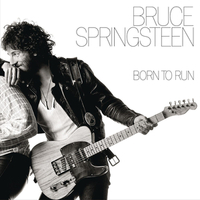

Eyeing his third album, Springsteen was conscious of the dangling axe (“Cult artists don’t last on Columbia Records”), but already had the title track in his back pocket to make him immortal. Born To Run’s minutely observed tale of loserville runaways was the anthem to end them all – its barrelling pace perhaps further stepped up by the band overrunning their studio booking – and it’s just the start.

From the almost-overblown operatics that mean Thunder Road sails just the right side of Meat Loaf, to the tinglingly wistful Backstreets and saxophonist Clarence Clemons blowing a gale on Jungleland, the Boss had arrived.

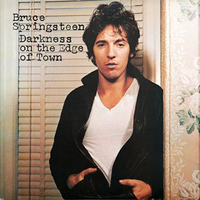

Darkness On The Edge Of Town (1978)

Three years of legal wrangles, followed by this less-accessible fourth album, burnt off a slice of Born To Run’s fanbase, but Darkness On The Edge Of Town has revealed itself as a creative pinnacle.

As stark as Frank Stefanko’s sleeve shot, peopled by last-gasp characters clinging to a kind of life, and spiced with the latent influence of British punk (“I felt a distant kinship to the class consciousness, the anger”), the record peaked with Racing In The Street’s bleak inversion of rock’s cars-and-girls fantasy.

“The songs from Darkness On The Edge Of Town,” Springsteen once noted, “are perhaps the purest distillation of what I wanted my rock‘n’roll music to be about.”

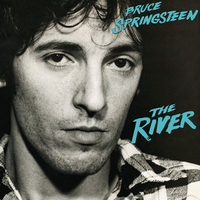

It started as Springsteen’s bid to bottle the live show – to “put more trash in our sound” – and the E Street Band duly rattled and shook the Power Station studio as their Boss demanded “the messiness, the realness, the can’t-get-out-of-each-other’s-way togetherness”.

In the end, though, The River became something else: a split-personality double album where exciting-if-unsubtle bar-room thunderers, like Cadillac Ranch and Ramrod, sat alongside some of his most affecting ballads – try the jazzy, sad-eyed sweep of Point Blank. All that, plus a US Top 10 hit with Hungry Heart and, at last, the first hints of a female fanbase (“Thank you, Jesus!”).

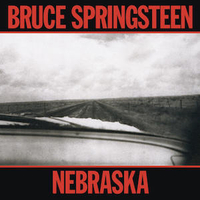

Influenced by a toxic mix of Flannery O’Connor’s gothic short stories, the cold violence of film-maker Terrence Malick, and the songwriter’s own childhood meditations, Springsteen saw Nebraska’s somber collection as a clean break from rock’s bombast, more like “black bedtime stories… restrained, still on the surface, with a world of moral ambiguity and unease below”.

The demos were made on a four-track cassette recorder – and Springsteen released them as such after finding that tracking the full band in a top-dollar studio only diluted his man-and-guitar power. There’s beauty in moments like Atlantic City – but it’s painted in the blackest colours of his career (“Everything dies, baby, that’s a fact”).

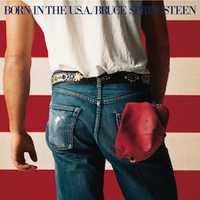

The eternally misunderstood title track led the campaign, and it was in good company, with the strongest pound-for-pound hooks of Springsteen’s career helping top up a fanbase he’d eroded with almost a decade of esoteric releases.

Born In The U.S.A. is big, bombastic – almost uncharacteristically crass, at points – but you can’t argue with stadium-tooled juggernauts like Glory Days and No Surrender, while the hushed chime of I’m On Fire is one of rock’s great studies of fit-to-burst lust.

Springsteen knew this was the dollars-and-cents peak, for better or worse: “I would never be here, this high, in the mainstream pop firmament again.”

Just as Springsteen had retreated after Born To Run, so he wilfully derailed his own post-U.S.A. ascent with Tunnel Of Love. Reflecting that he’d “had enough of the big time for a while”, and spitting out deeply personal songs about time, death and the travails of marriage, Springsteen cut the E Street Band loose and returned to the Nebraska model of bare-bones, largely solitary multi-tracking.

The title track, Tougher Than The Rest and especially Brilliant Disguise – a pained ballad admitting the impossibility of ever truly knowing someone – seemed wrung from the heart, and so it proved: Springsteen’s marriage disintegrated the following year.

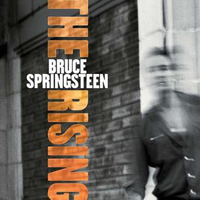

Devils And Dust and 2019’s Western Stars run it close, but The Rising deserves the nod as Springsteen’s finest post-millennial release. As a febrile nation processed 9/11, the E Street Band’s reunion could hardly have been more timely (“Our band was built well, over many years, for difficult times”).

Leading them, the Boss brought songs that extrapolated from that terrible day to meditate on love, courage, absolution and the afterlife, while pointedly including voices from across borders (Worlds Apart features Pakistani Qawwali singer Asif Ali Khan). And if that was too heavy, there was always the unapologetic rave-up of Mary’s Place.