It was the summer of ’84. Bryan Adams was in New York City, working on the follow-up to his breakthrough album Cuts Like A Knife, which had sold a million copies in the US. The new songs he’d recorded were good. He was sure of that. And he had what he considered the perfect title for a rock’n’roll album: Reckless. But still, he had a feeling in his gut that something wasn’t quite right.

Adams and his producer Bob Clearmountain were at The Power Station, a famous recording studio on West 53rd Street in Manhattan. They were on the final stretch: nine tracks had been recorded at a different studio, Little Mountain Sound in Vancouver, the Canadian city where Adams had lived since he was a teenager. Now they were applying the finishing touches, mostly vocal overdubs. But while Clearmountain was happy with what they’d got, Adams was not.

His instinct told him they needed something more, but he was too close to it to figure out exactly what was missing. He was also fatigued. He and Clearmountain had been working the graveyard shift, from six o’clock in the evening through to six in the morning. Adams was also sleeping on the couch at a friend’s house because he was sick of staying in hotels.

But in his tired mind, one thing was certain. This was no time to be dropping the ball. In 1981, after his debut album had flopped, he had joked about naming the second Bryan Adams Hasn’t Heard Of You Either. Three years on, his mood was more serious. With Cuts Like A Knife, he’d gotten his foot in the door. With Reckless, he intended to bust it wide open. Everything about this record had to be perfect.

Adams summoned his manager Bruce Allen to New York for a playback of the album. Allen’s verdict was straight to the point: “Where’s the rock?”

According to Adams, these three words “changed everything”. The next day, he was on a plane back to Vancouver. He called Jim Vallance, his co-songwriter, and told him: “We need to pump up the volume on this.” With his manager’s words still ringing in his head, Adams chose two tracks that could be “taken up a notch” – One Night Love Affair and Summer Of ’69. In addition, he and Vallance wrote a new song from scratch – a song that answered Bruce Allen’s question in the most emphatic fashion. Its title: Kids Wanna Rock.

The three tracks were re-recorded using a drummer that Adams discovered playing in a ska band in a strip joint. And with that, he knew, at last, that he’d nailed it.

With Reckless, Adams found a niche that was all his own. As a rock record made for radio, it plugged into that mainstream audience dominated by Bruce Springsteen, John Cougar Mellencamp and Don Henley. But Adams was of a different generation to those established big-hitters. He turned 25 on the day Reckless was released – November 5, 1984. His hard rock sensibility – explicit in Kids Wanna Rock – was something that spoke to fans of Van Halen and ZZ Top, and the way he sang, belting it out like a young Rod Stewart, gave him that extra edge. With Reckless, Bryan Adams would knock the ball clean out of the park.

When Adams talks about the making of Reckless and the events leading up to it, the story he tells is that of the archetypal working class hero. “Writing songs,” he says, “is like making anything – you have to put the time in for it to work. I’m the guy who has to really graft it until something comes out.” His image, or lack of it, has its roots in the values he learned as a kid. “The way I was brought up, you couldn’t really put on any airs and graces.” And when he thinks back to his start in the music business – when he states, flatly: “I came from absolutely nothing” – he is not bullshitting.

This much was evident to Jim Vallance when he first met Adams at a Vancouver music store in 1978. “Bryan was unemployed, penniless and living with his mom,” he says. At the time, Adams was 18, and had already taken his first steps as a professional musician. Three years earlier he had made his debut recording as the singer for glam-rock band Sweeney Todd. “I wanted to be the guitar player in a band,” he says. “I never wanted to be the frontman. If I could have been anyone, it would have been Ritchie Blackmore.” But by the time he met Jim Vallance, he was set on being a solo artist.

For Vallance, the timing of that meeting was perfect. At 26, he had recently quit playing drums for the hard rock group Prism to work solely as a songwriter. He had written all of the songs on the first Prism album under the pseudonym Rodney Higgs – his logic being that if the album failed, his career would not be ruined. In the event, the album went platinum in Canada, and Vallance would continue to write for the band. But he was also looking for other artists to work with, and in Adams, he sensed a huge potential.

“The first day we got together, I knew he was going places,” Vallance says. “He was only eighteen but he was overflowing with confidence. Not in an arrogant way, more like bursting with energy and ideas. Right away I’m thinking, ‘Wow, this kid can sing and write songs.’”

For months, they worked together in the tiny studio that Vallance had in the basement of his house. “We’d spend every day just busking,” Adams says. But there would be no short route to success for Bryan Adams. “For a long time,” he admits, “nobody gave a shit about me.”

Before he found a manager, Adams approach, hocking his demos to various labels. It was a chastening experience. “I remember this one record company guy said to me: ‘You got a band?’ I said: ‘No’. ‘You got a manager?’ ‘No.’ He said: ‘You’re wasting my time. See ya!’”

When Adams eventually got a contract with A&M Records at the end of 1978, it was for a nominal fee of one Canadian dollar. “They signed me as a songwriter initially,” he explains, “with the provision that they would allow me to make an album. And I got the shittiest deal. But I was grateful for the break. To have someone at least give you a chance, it was all I wanted.”

His first album, self-titled, was released in 1980. It was a low-budget affair, what Adams describes as “a glorified demo session for Jim and I”. The album failed to chart outside of Canada, and even there it stiffed. From this he learned a valuable lesson. “There’s writing songs, and there’s making a record – two different things. To take it to the next level I needed a producer.”

To this end, he travelled to New York to hustle Bob Clearmountain into listening to his songs. To a point, the plan worked. Clearmountain produced the second album – named You Want It You Got It, after Adams’s original joke title was “kiboshed” by A&M. It sounded good. But again, sales were weak. In the US, the album didn’t even make the Top 100.

It was only in 1983, with his third album, Cuts Like A Knife, his first great record, that Adams started to get some traction in Canada, the US and beyond. Boasting a punchier sound, and boosted by the swaggering title track and the piano ballad Straight From The Heart, it reached the Canadian and US Top 10.

In late ’83, A&M bosses presented Adams with a platinum disc for one million sales. And in this moment of triumph he learned another lesson about the music business. As he held the award and posed for photographs, he whispered to his manager: “Bruce, I haven’t been paid for this.” The reply was typically blunt. “No, and you’re not gonna be paid. They’ve taken the money. Everything you’ve done for the last three years, they’ve been paying for.”

When he got home to Vancouver, Adams had the money to pay the rent on his apartment, and just enough left over to buy a car. Not a Ferrari, but a Volkswagen Beetle. Second-hand. And again, the advice that he received from Bruce Allen was succinct. “You better write another new record…”

When Adams thinks back to the earliest stages in the making of Reckless, he says that his strategy – what little there was of it – was very simple. “I wish I could say I had a game plan,” he laughs, “but I didn’t. I was just trying to keep the ball rolling, trying to pay the bills. That was all I was trying to do.”

Adams’s music was formed by an unashamedly populist sensibility, his market position neatly summarised in a predictably sniffy review of Cuts Like A Knife in Rolling Stone. For critic Errol Somay, the album was “bland”, rock’n’roll at its most vanilla. “Time again,” he wrote, “Adams pays tribute to the influential arena acts of the past several years – e.g. Foreigner, Billy Squier.” Grudgingly, he predicted that stardom was “imminent for this golden boy”.

Such criticism meant nothing to Adams. He didn’t aspire to be the next Dylan, nor was he making the kind of socio-political statements that lent gravitas to the work of Springsteen. In truth, Adams was as much a working class hero as the latter, except that Adams didn’t make this a part of his act. “For me,” he says, “there was no message, no trying to be a man of the people. I was just trying to write great songs.”

He was also smart enough to know exactly how he should up his game. Supporting Journey on the enormo-dome circuit, he realised that he needed more songs that could connect to big audiences. “I was scrambling for live songs,” he says. “I was doing whatever I could to get the crowd going, but I needed a better setlist.” In short, he needed anthems. Reckless would be an album full of them.

Even before Adams and Vallance began intensive writing sessions back in Vallance’s basement, they already had a handful of tracks in various stages of development. Among them were the ballad Heaven, recorded in 1983 as the theme to the flop movie A Night In Heaven; One Night Love Affair and Run To You, a track that had been written for Blue Öyster Cult and subsequently rejected by the group.

Adams was surprised that BÖC had passed on Run To You, given that its opening guitar riff echoed their classic 1976 hit (Don’t Fear) The Reaper. But when he went back to the song, it sounded better than he had remembered – so good, in fact, that he wondered why he hadn’t thought to keep it for himself. And once he and Vallance got into their rhythm in those basement sessions, more songs came in quick succession. “It was almost as if every day we got together another song would happen,” Adams says. “Monday would be Somebody, Tuesday would be She’s Only Happy When She’s Dancin’, Wednesday would be Summer Of ’69…”

The latter song, originally titled Those Were The Best Days Of My Life, was inspired by another great American rock hit from 1976, Bob Seger’s Night Moves. “That’s such a brilliant song,” Adams says. “It always pissed me off that I didn’t write it.”

What resonated so powerfully with Adams were the lyrics in Night Moves, its portrayal of adolescent rites of passage, with images of cars and girls and long, hot summers. “It’s a nostalgic song,” Adams says. “Romantic. Teenage blues, that awkwardness of trying to figure out sexuality – it’s all there.”

The song’s title was a rude joke that stuck. “I always got a laugh out of it,” he says. So too the final line: ‘Me and my baby in a sixty-nine.’ “I really nailed it there,” he says with a proud laugh.

For Adams, it was important that Reckless had something of the energy and vibe of a live performance. When recording began at Little Mountain in March 1984, he cut most of the tracks ‘as live’, backed by members of his touring band – lead guitarist Keith Scott, bassist Dave Taylor and keyboard player Tommy Mandel – plus session drummer Mickey Curry. With Run To You, all they needed was one take.

“I’m proud of that,” Adams says. “I remember Bob Clearmountain standing up in the control room and saying, ‘Whoah! You guys have gotta hear this!’ And when he played it back, I said: ‘Let’s not touch that. Next song!’ We did record it two or three times afterwards, because we could. But we never got it as good as the first one.”

Another song that came together quickly was one that Vallance had brought to the table. It’s Only Love wasn’t written with a vocal duet in mind, but Adams felt it needed another voice, “to make it special”. And he had only one candidate in mind: Tina Turner, the soul singer who had recently launched her comeback with the single Let’s Stay Together. A demo of the song was sent to her management, and a meeting arranged for when Turner was doing a show in Vancouver as support to Lionel Richie. Adams admits he was nervous as he waited for her backstage.

“And then,” he says, “I saw this big mane of hair coming down the hallway. I could hear her saying, ‘Where is he? Where is he?’ Someone said: ‘There he is.’ And Tina says, ‘Bryan, I loooove this song! I wanna record it!’ I said: ‘Let’s do it tomorrow.’”

She agreed. He thought to himself: I’ll believe it when I see it. But on the following afternoon, Turner arrived at Little Mountain to deliver a performance that left Adams and his team feeling like they’d been hit by a force of nature. “After we’d recorded it and she said goodbye, it was like a tornado had just ripped through there. I said: ‘Bob, could you just play that back? You definitely got that on tape, right?’ He said yes, thank God.”

The album was eventually completed in August, with the re-recording of One Night Love Affair and Summer Of ’69, and the addition of Kids Wanna Rock. “Those were the missing ingredients that it needed,” Adams says. “And I give credit to my manager for that.”

He also credits Jim Vallance as the inspiration for Kids Wanna Rock, a full-throttle rock’n’roll blaster with a ridiculous, gonzoid lyric, its title coined by Vallance in a moment of evangelical fervour after he and Adams had attended a concert by synth-pop boffin Thomas Dolby.

“After that show,” Adams recalls, “Jim was so emphatic about the fact that people just weren’t getting into the keyboard thing. Jim’s a rocker, man, and he wasn’t gonna have it. He just said: ‘The kids wanna rock!’ And I thought that was so funny.”

Adams knew before Reckless was released that it was a good record. He was certain that among its 10 songs were some of the best he had ever made. Jim Vallance, the man who believed in Bryan Adams when nobody else did, remained pragmatic. “In Bryan’s career, up to Reckless, each album had done better than the one before,” he recalls. “I was confident Reckless would do better than Cuts Like A Knife. I just wasn’t prepared for how much better.”

Run To You was the first single. It reached No.4 in Canada, six in the US, and 11 in the UK. And the hits kept on coming. Most spectacular of all was the success that Adams had in the US, where six singles from the album made the Top 15; a feat achieved only by Michael Jackson with Thriller and Bruce Springsteen with Born In The USA. In June 1985, Heaven topped the US chart. Two months later, Reckless did the same.

His celebrations were modest: a few drinks, nothing more. Adams was never a big drinker. “It never interested me,” he says. In his distant past – “as a kid” – he had experimented with soft drugs. But in an era when cocaine use was effectively de rigueur in the music industry, at all levels, drugs had no appeal for Adams. “I was too focused,” he says, “way too focused to go off the rails. None of the guys in the band were drinkers. Certainly, nobody was doing any drugs. I wasn’t interested, and it wasn’t around me.”

It also helped that Adams had, at a time when the pressures of global fame were upon him, a girlfriend who understood the strangeness and complexities of a life in show business. Vicki Russell was the daughter of British director Ken Russell, whose films include the big-screen version of The Who’s rock’n’roll musical Tommy – in which a young Vicki played the role of the reverend’s daughter-turned-groupie, Sally Simpson.

“Vicki was a great girlfriend and fantastic character to have on tour,” Adams says. “She could see through the bullshit way before I could. Someone would come up and say, ‘Hey, really nice to meet you!’ And she’d just say in my ear, ‘Wanker!’ She was a perfect foil for me.”

Vicki also had an appreciation of the absurdities of the rock’n’roll lifestyle. “While we were on stage,” Adams says, “she would go out into the crowd and find three or four girls and bring them backstage, and when we walked into the dressing room, these birds were all topless! Brilliant!”

In the end, it was Adams who called time on the Reckless campaign, against the wishes of his manager and record company. “If they could have pulled one more single off it, they would have,” he says. “And when I told Bruce, ‘I gotta go home,’ he said: ‘No, man, keep going!’ But I stopped the tour. I’d been away from home for such a long time. Two years. I was exhausted.”

And at this point, he could afford rather more than an old VW Beetle. “I got paid, finally,” he says. Adams bought a house in Vancouver. He also did what every working class boy dreams of doing, if and when they make it big.

“I bought my mum a house,” he says with pride. “I took care of everybody. That felt pretty good.”

All these years later, Adams describes Reckless as “the best album I ever made”. It was, he says, “the culmination of a lot of really good energy and good songs coming in at the right time. Jim and I were at our peak as songwriters, and the record was made with real musicians, which is why it still sounds good. When it was simple, that’s when it was the greatest.”

For Adams, so much has changed since then. In those 30 years he has made six more albums, some good, others less so. And for all the success that he had in the early 90s with (Everything I Do) I Do It For You – No.1 in 18 countries, including 16 straight weeks in the UK – it came with a price. It defined him in the public consciousness as a balladeer – something he has never really shaken off.

But with Reckless, it was a different story. It was an album with more hits than most artists’ greatest hits. But above all, it had balls. In answer to that question – “Where’s the rock?” – it had enough to make it the album of the year in the 1985 Kerrang! critics’ poll, ahead of heavyweights such as AC/DC, Iron Maiden and Aerosmith.

Reckless isn’t just the best album that Bryan Adams ever made, it’s also one of the great rock albums, period. “I gave that record everything I had,” Adams says. “Even now you can feel that. And, you know, a great song is a great song. That’s what stands the test of time.”

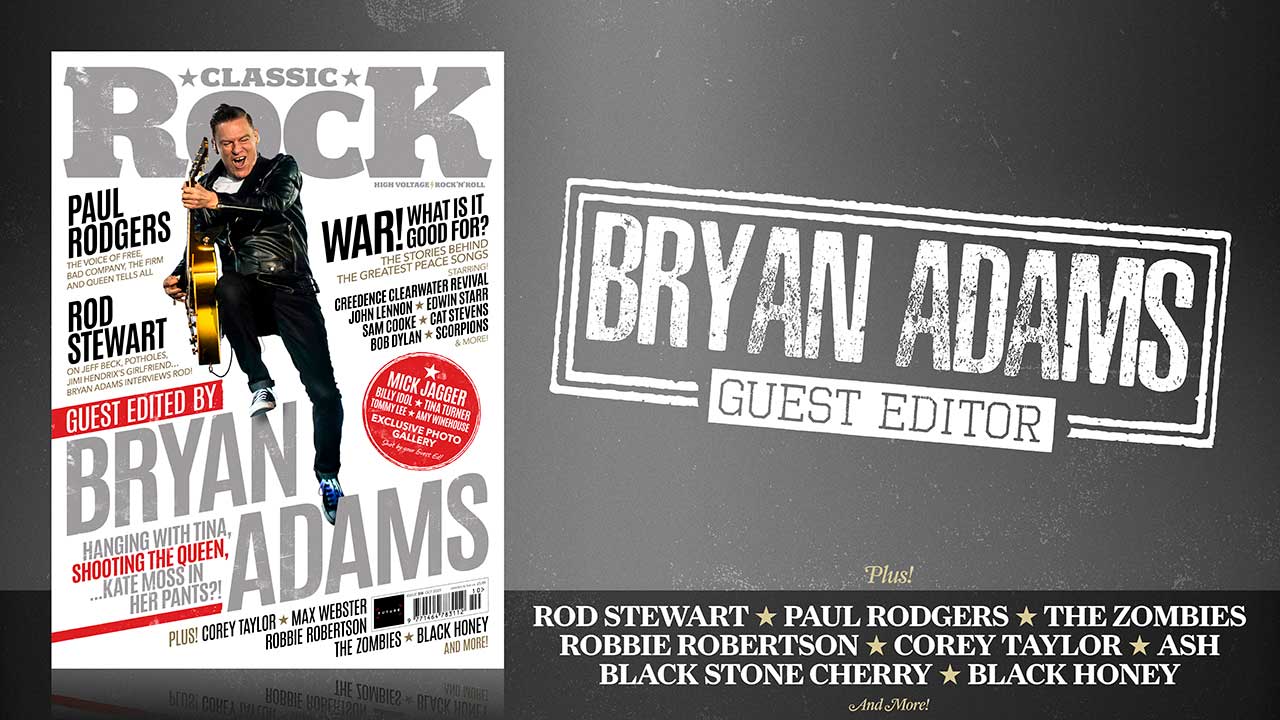

Issue 319 of Classic Rock magazine, guest edited by Bryan Adams, is available to buy online.