Buddy Guy will never forget how the Chicago blues scene saved him. “I’d not eaten for three days, I was hungry, I was cold. I was carrying my guitar, walking the streets on the south side, and I was thinking I might have to beg a dime from someone so I could call my mother to ask her to send me my train fare back home,” he tells The Blues in serious tones. “But then this stranger, he took pity on me, he heard me playing some Jimmy Reed, he grabbed my hand and took me along to the 708 Club. Man, I couldn’t believe my eyes and ears. I walked in and the place was jumpin’. The music warmed my soul. I recognised the song that was playing immediately, it was Otis Rush’s I Can’t Quit You Baby. It was no copy though, it was Otis Rush himself. I knew I was in Chicago then, that this is what I’d come for.”

This was winter 1957, and that night at 708 East 47th Street in Bronzeville, Chicago, the 21-year- old, born and raised in Lettsworth, Louisiana, ended up on stage, Les Paul Gibson in hand, peacock-strutting across the boards, playing Bobby Bland’s Further On Up The Road with his guitar behind his back, over his head, played with his teeth. Otis Rush lapped it up, the audience did too. Word got out and before the end of the night Muddy Waters had turned up with a salami sandwich to feed him. “I didn’t believe it was him at first, but that was Chicago though, you walked down a street and you’d come to a corner and you’d find Muddy, Wolf, Little Walter, Sonny Boy… a blues giant doing his thing.”

That night, Buddy Guy and Muddy Waters struck up a friendship that would last Muddy’s lifetime.

Throughout the fascinating half-hour conversation The Blues has with Buddy Guy, talk time and again finds its way back to Chicago, the city the musician has called home for 58 years.

“It’s where I came of age, it defined me,” he says affectionately. He arrived in the city on September 25, 1957, the date imprinted indelibly on his memory, looking for work at the university. “I was told I’d make twice as much money there than the Louisiana State university where I had been working. My mother was sick, she’d had a stroke, I was trying to support her, my plan was to work in the day then spend the evenings watching Muddy Waters play guitar at night. I never thought I’d be a professional musician, I didn’t think I was that good. I was shy but after Muddy, Wolf and BB King told me I really was good, I thought I’d better keep on playing.”

It was at the 708 Club that he also made friends with BB King. “I was on stage at the 708, playing his song, I looked out into the audience and there he was. I got stage fright, had to take a break. I went to the bathroom, when I came out, he called me over to him. He said he saw a lot of him in my playing. I couldn’t believe it, not only had he come to hear me play but he liked what he heard. He said: ‘You’re ready to take my place.’ I wasn’t sure about that but it was always an honour to be in his company.”

Another Chicagoan friend of Guy’s, Magic Sam, got him his first record deal. At Eli Toscano’s Cobra Records, under producer, songwriter and bassist Willie Dixon’s supervision, Guy recorded his debut 45 Sit And Cry (The Blues). In 1958, it was released on the Cobra label imprint Artistic.

“After playing the 708 club word got out about me,” explains Guy. “Most guitar players in Chicago at this time were sitting down to play but here was this guy who was wild, crazy, with a 150ft guitar lead, that would start playing from outside the club then come in and jump off the stage and play in the crowd. Of course I’d got that from seeing Guitar Slim and T-Bone Walker back in Louisiana.”

Magic Sam was taking part in Battle Of Guitars talent contests, which took place on a Sunday afternoon at different bars around the city.

“I got playing in them, started winning them, and got to know him, Matt Murphy, Wayne Bennett, all these great guitarists. One afternoon after I’d won again, Sam said he’d take me to his record company, see if they’d record me. We got there, it was a tiny studio. Harold Burrage, the vocalist, was there. I couldn’t believe it, I knew Harold Burrage’s 45s. Anyhow they plugged me in, I played three notes of BB King’s Sweet Sixteen and Harold Burrage’s jaw dropped. Eli Toscano put this contract in front of me and said: ‘Sign this, we’re gonna make a record with you.’ It was a funny set-up. I didn’t get no freedom. Willie Dixon was in charge, he told me what to play and how to play it and I did as he told me.

Guy still savoured the experience though. “It didn’t matter because it was my first time in a proper studio and I was so nervous and so excited. There were two microphones, one for me, one for the band. The band was Willie Dixon on bass, Otis Rush on rhythm guitar, Odie Payne on drums, Harold Burrage on piano and McKinley Eaton on baritone sax. The A-side Sit And Cry, well that’s just how I felt sitting in the studio that day.”

The B-side, Try To Quit You Baby, was an answer record to Otis Rush’s I Can’t Quit You Baby. “That was Eli Toscano’s idea, and having Otis Rush playing on it too, I couldn’t be happier. It was like I’d gone to heaven.”

Sit And Cry (The Blues) and its follow-up, 1959’s This Is The End – the latter of which was heavily influenced by BB King – flopped though, and by 1960 Cobra had been declared bankrupt. Guy, undeterred, kept on performing and the following year he ended up at Chess, where he remained for seven years. Chess was located at 2120 South Michigan Avenue, and was at the height of its power.

The first time Buddy Guy went to Chess, he had a demo tape in his hand. No one was interested in the tape but his Les Paul Gibson caught the eye of Wayne Bennett, who asked to borrow it for a session with the doo-wop vocal group The Spaniels. Guy got to watch the recording of the session, left his own tape for Leonard Chess but heard nothing back. The second time he went to the building, though, it was a different story: he got a record deal.

We were all so in love with the music, there was no rivalry. We were a family. Everyone was having fun.

“Otis Rush took me to Leonard [Chess, co-owner of the label with his brother Phil]. Leonard apparently had asked Otis to bring me over to audition with him. Sam came along too. They didn’t take Sam, but they took me and Otis. I don’t know why they didn’t want Sam.”

The first session he recorded there was with Howlin’ Wolf. “I kept quiet, listened real well, did what I was told and because I did that, then I got the call that I was backing Muddy, Sonny Boy [Williamson], Koko Taylor, Little Walter. That was an education. Little Walter, he put the harmonica on the map. I got to know him real well, I played on two or three of his albums. We bonded because we were both from Louisiana. We’re trying to come up with a blues festival in honour of him in Alexandria, Louisiana at the moment. But before he made Juke, the harmonica, you could buy one for 10, 15 cents, then after that 45, it just exploded, everyone wanted to play the harmonica. It was like after BB King played the guitar on 3 O’Clock, before that you’d go into a little music store, they’d say make me an offer on the guitar. After 3 O’Clock, oh well, that costs such and such now.”

With so many legends living and working such a short distance from one another, ego could have been a problem. “But we were all so in love with the music, there was no rivalry, there was this sense of real camaraderie, we were a family. Everyone was having fun. The rivalry at the Battle Of The Guitars, we played that up, it was just an act, we made the audience think that, but the fact of the matter was, we were all stealing licks from one other, trying to get the best sound and enjoying ourselves.”

But his time at Chess didn’t work out quite as he had expected. “They didn’t go out and explode me and Otis like they had Muddy,” he says. “They gave me a 45 once every two to three years, they really just got me backing everyone else on the label there. They even had me playing on some spiritual recordings. It was only after the musicians in the UK started namechecking me that Leonard got interested in me and came to the studio to see me record. That was the only time. Before that I was working with Willie Dixon and Ralph Bass.”

Chess really missed a trick with Guy; here was a seditionary who, pre-empting Jimi Hendrix’s onstage theatrics, could ignite a crowd, who in the studio pushed boundaries using feedback, distortion, extended solos, who wanted to record albums like Muddy Waters’ Electric Mud and Howlin’ Wolf’s The Howlin’ Wolf Album before psych blues had even been invented. Nevertheless, the handful of singles he recorded for the label contained some future classics; his label debut The First Time I Met The Blues in 1960, 1962’s Stone Crazy and 1967’s I Suffer With The Blues are the pick and all ripe for rediscovery, capturing an excitement, enthusiasm and raw energy that trademarked Chess R&B.

It was in February 1965 that he went to the UK for the first time, found out he had an audience and never doubted his talent again. “It was a huge boost to know people were actually listening. There was Jimi Hendrix, Rod Stewart, Jeff Beck… they were all fans.”

Seven months later he visited again as part of the American Folk Blues Festival European tour. It was on that tour that he forged another important relationship, this time with Big Mama Thornton. “That was the first time I met her and I’m playing lead guitar for her. She starts singing Hound Dog – I’m a big fan of the record, her version and Elvis’ – she’s jumping around on stage and with that her bridge falls out of her mouth. And without missing a note, she picks it up off the stage floor and puts it straight back in and keeps singing. That summed her up, she didn’t make no fuss, she was no-nonsense and just got on with it. She didn’t bite her tongue about saying nothing either.”

That same year, Guy teamed with harmonica player Junior Wells, guesting on Wells’ terrific Hoodoo Man Blues album for Delmark under the pseudonym Friendly Chap. They’d continue working together up until Wells’ death in 1998.

You never had to walk more than two blocks to come across great music. That’s what made Chicago great.

Like so many of Guy’s close friendships, theirs began at the 708 Club. “He was playing in Muddy’s band. I couldn’t take my eyes off him,” says Guy fondly. The pair clicked immediately, like two peas in a pod. “He approached the blues like me, he was a wild one. We started jamming in the little clubs in Chicago together, I was running around with my 150ft wire, I made him get a wire for his harmonica. The first time we played the Newport Jazz Festival in 1960, no one had heard of us, we were blues artists at a jazz festival. In the afternoon they ran these guitar workshops. You’d go to a small stage tucked away in the corner, you’d have a little band behind you and you’d get an audience of 100 to 150 people watching. It was supposed to be intimate. We started warming up – I was on one side of the field, he was on the other. We started playing, and we knew each other so well, knew what the other was going to do, we met each other in the middle and bang! Suddenly we had 15,000 people watching us. We had them excited, up on their feet, clapping their hands. George Wein, he’s the man who created the Newport Jazz Festival, he came over and said: ‘Who the hell are you guys? We’ve never had that many people at a workshop before.’ BB King was in the audience and the next thing I know, he and Junior are out gambling dice on the grass at the front of the stage with the fans.”

In 1967, Guy left Chess and signed to Vanguard, expanding his musical palette to include soul and funk on 1968’s A Man And The Blues. He continued playing live, and never strayed far from Chicago during the 70s and 80s; in June 1989 he pledged his allegiance to the city further, opening Legends, his blues club at 700 S Wabash Avenue. It’s there he played his last show with Junior Wells and he still plays there every January, selling out a 16-date residency. “That sure is fun,” he says. Then in 2012 he brought his love of Chicago full circle by asking US President Obama to sing Robert Johnson’s Sweet Home Chicago with him when he was a visitor at The White House. “And he did,” says Guy. “That was a proud moment.”

But Buddy Guy misses the old days. “I sure wish Chicago was like it used to be,” he sighs. “Because, you know back in the 50s and 60s, I never got to play all the blues clubs in the city because there were just too many of them. It would get to summer, you’d leave home just as it was getting dark, all the doors of the clubs would be flung open as there was no air conditioning and you’d hear a harmonica playing and a guitar playing and you’d think, that sounds like Little Walter or Muddy Waters or Howlin’ Wolf. And most times it wouldn’t be, it would be a local guy, but he’d be good and you’d go inside and take a listen and you’d have a drink and you’d never make it to where you left home to go to. You never had to walk more than two blocks to come across great music. That’s what made Chicago so great.”

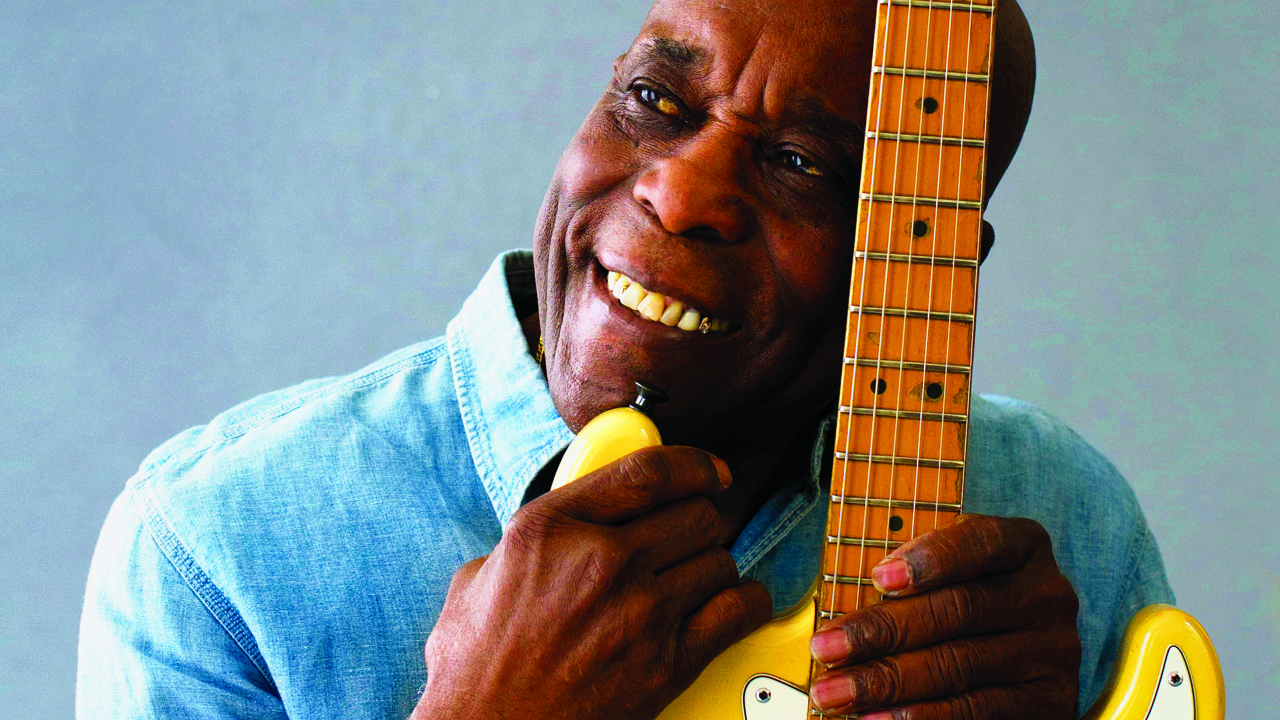

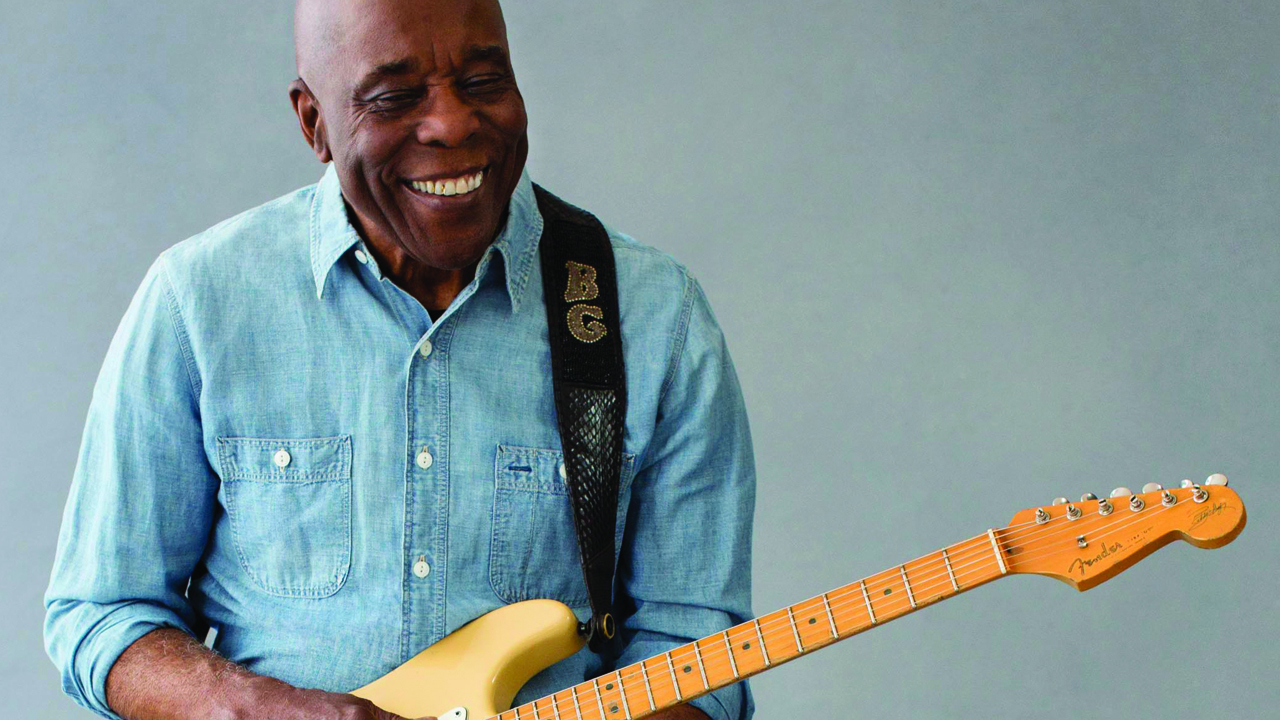

**Guitar Hero: Buddy Guy on the new album…

**“The album is titled Born To Play Guitar because I was born to play guitar. Guitar Slim was the one who taught me the most, he was real crazy on stage. He’d be running up and down the stage, jumping off his amplifiers. I took that and added some T-Bone Walker, started playing the guitar above my head, behind my back, with my teeth. I got myself this long cable so I could start playing outside a club to get the audience all excited and then make a big entrance. No one else was doing that at that time. It got me attention. Chess Records didn’t like my style, but once I got to London, I found I had a fanbase.

Even though Chicago is my home, I’ve recorded albums with [producer] Tom Hambridge in Nashville. Tom is great to work with, he really understands me. It helps because we’ve played live on stage together, we know each other, what makes us tick, what each of us is best at. It’s much better than a relationship based on mailing a song back and forth to one another. The way I record with Tom, it reminds me of my days at Chess. You just close the doors and have your way. Tom doesn’t come in and point fingers, we just go in and have fun, we’re always smiling. And Tom, he reminds me so much of the late Willie Dixon.

I’ve got some great guests on this album. I’ve got Tom to thank for that. He can hear who will add to a song and he’ll suggest this person or that person and then he figures out just how to get the best out of them, like getting Joss Stone to sing on a cover of Brook Benton and Dinah Washington’s Baby You’ve Got What It Takes with me. Billy Gibbons, he’s on a track called Wear You Out. I’ve known Billy for a long time, he’s great to jam with, he’s a big blues fan, he knows all about Muddy, Wolf, Sonny Boy. He looked me up, knows my history and when we met we clicked. Guys like Billy, you say: ‘Hey, I’m doing an album, would you mind?’ And they say: ‘Just tell me when.’ Me and him we’re like gumbo – we’re different but if it’s in the pot, it’s going to be good.

Now Kim Wilson from The Fabulous Thunderbirds, I’ve known him even longer than I’ve known Billy Gibbons, and it made sense to do a cover of Little Walter’s Too Late because he just loves Little Walter. There’s Van Morrison on Flesh & Bone, that song is dedicated to the late BB King. There’s a tribute to Muddy Waters on the album too, called Come Back Muddy. I knew this day was coming, when these greats would die, we all knew we wouldn’t live forever and we’d talk about it. I talked about it with BB, with Muddy, with Albert King, with Freddie King… we’d stay up all night talking about the blues and how whoever went first, the one left on earth had to keep the blues alive. That’s what I’m doing, keeping it alive for them, for everybody to enjoy.”

Born To Play Guitar is out now via RCA