This article first appeared in The Blues Magazine #1.

More than a decade Buddy Guy’s senior, that genial patriarch BB King is still the Chairman Of The Board Of Blues Singers. But George ‘Buddy’ Guy – once an awestruck teenage fanboy come to Chicago to worship at the feet of South Side deities like Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf – has no living challengers for the portfolio of the blues’ Chief Executive Officer. Muddy and Wolf are gone – as are John Lee Hooker, Albert King, Albert Collins, Freddie King, Little Walter, Junior Wells and too many more – whilst Otis Rush and Bobby Bland are pretty much retired. Of the original titans – the Real Guys – Buddy is the last man standing, and the last man still bringing it like it was brung back in the day.

“Those people like that – once in a lifetime…” Guy reflects. “John Lee Hooker, Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, just pick ’em out yourself. Sonny Boy Williamson, Little Walter, just name me somebody that come close to those guys at bein’ what they are. There are musicians that come along since that are more famous and everything, but in the long run, somebody will say a Muddy Waters or a John Lee Hooker or a Howlin’ Wolf. Regardless of how good they are, how famous they are, they have to mention those people, because they had something that I don’t think no one will ever replace: that tone of John Lee, that tone of the Howlin’ Wolf and people like that.”

Yeah, but how about Buddy Guy?

“I don’t know about that! Buddy Guy is like a copycat. I learned all of my stuff from those people, man. I guess knowin’ them – and I played with even Lonnie Johnson before he passed away, man – I’m one of the luckiest guys you know. I played with him, I held a conversation with Arthur Crudup and they all told me the same thing: ‘Yeah, we learned it from someone else too, Buddy, that’s where we got ours from’. So I guess some time or another, someone probably will say ‘Buddy Guy’. At the very least, it’ll help keep alive the music I’m so dedicated to and so crazy about. I wish it could live forever.”

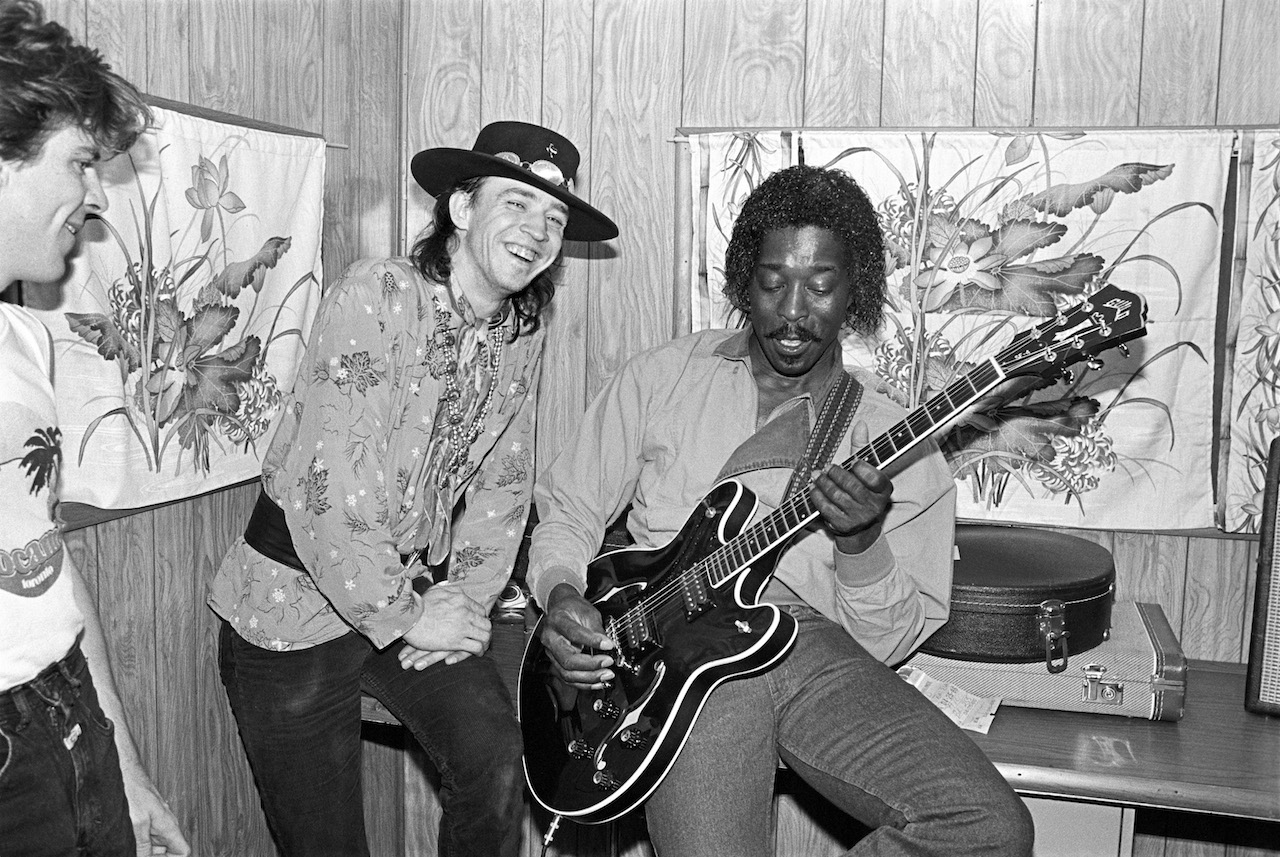

Buddy Guy is indeed a hero and an influence in his own right, upon Jimi Hendrix, Jeff Beck, Eric Clapton and Stevie Ray Vaughan, to name but four of many. In Martin Scorsese’s Rolling Stones concert-movie Shine A Light, he shows up to tear the Stones a new one on a smoking version of Muddy Waters’ Champagne And Reefer (incidentally causing a few apoplectic fits amongst his sponsors at Fender by wearing a Gibson promotional shirt). He’s racked up half a dozen Grammy awards; he owns and manages Legends, Chicago’s most famous blues club, and, in February 2012, he played at a special blues concert in the White House, alongside BB King (who managed to cajole the increasingly vocal Barack Obama into singing a verse of Sweet Home Chicago), Jeff Beck, Booker T and Mick Jagger. However, as he recounts in his newly-published autobiography When I Left Home (co-written with David Ritz) the road from Letchworth, Louisiana, to the White House has been a long and bumpy ride.

Despite having been one of the most hysterically exciting singer-guitarists ever to tread a blues stage since around 1960 – when he cut his first masterpiece, First Time I Met The Blues, for Chess Records – he spent most of the 1960s augmenting his musical income by driving a truck. Following Buddy Guy & Junior Wells Play The Blues, a botched 1972 album notionally co-produced by Eric Clapton and Atlantic boss Ahmet Ertegun (the former was smashed most of the time and the latter preferred to spend his days hanging out at the beach) Buddy was without a record deal for almost 20 years.

Well, hell, Lulubelle… No one ever said playing the blues was an easy life. Buddy just kept on going. “I never was taught anything by anybody,” Guy offers. “My talent is a God-gifted talent, and I’m very religious in that respect, and I think God put me here for a reason, and not a season. Didn’t nobody teach me, and I guess I was just born with that in me, and I think He put me here for that. I just give you 110 per cent of Buddy Guy, and when I finish playin’ in any concert, I sleeps well. If you don’t like me don’t come see me, because I intend to make you like me. But who can win everybody? The ones that don’t like me, they can go say, ‘I don’t like him, but he did do the best he could’.”

The first song Buddy Guy ever learned how to play, back on the farm, was John Lee Hooker’s Boogie Chillen. “I was half asleep,” he remembers. “My brothers and sisters had ran me out of the house with an acoustic guitar. Don’t know how to tune it, don’t know how to finger it, and you know what I’m talkin’ about if you in the house with somebody that can’t play nothin’, so they say ‘Mama, get him outta here.’ Down South in Louisiana this time of year, you can go out and lay in the sun, and if the wind’s not blowin’ it’s warm. So I was layin’ out there on a woodpile just pickin’ away, and I dozed off. And when I woke up I had a riff like Boogie Chillen and I played it for six hours, because I thought if I move my fingers I never would find it again. I went and found all of my country friends, which is about four, and I said ‘I got it’. And that was the first thing I learned how to play that I knew sounded right when someone would listen. And each time I got to one of ’em that followed me, I’d say ‘I got it’. ‘Yes, you got it, that’s it.’ I’d say ‘I got this John Lee Hooker’, and that’s the first thing I learned how to play.”

The first ‘name’ bluesman Guy ever saw perform, at a local store, was Louisiana legend Lightnin’ Slim. But the real eye-and-ear opener was the Strat-slinging Guitar Slim, best-known for The Things I Used To Do (arranged and piano-ed by a then-unknown Ray Charles) and the most spectacular showman on the scene. Dressed way past the nines with matching suits, shoes and hair-dye, louder than a muthafucker and all over the stage where most of his competitors still performed sitting down, Lightnin’ Slim taught the teenage Buddy everything he needed to know about performing, as well as singing and playing the blues.

Newly arrived in Chicago with little more than a guitar and a change of clothes, Buddy jammed all over the South and West Sides, and it wasn’t long before he came to the attention of Muddy Waters and Willie Dixon. He spent most of the 1960s at Chess, playing as a studio sideman for the label’s biggest stars and cutting the occasional single under his own name, but he never got to make an album for Chess, and was rarely allowed to crank his amp and wail. One occasion where he could was Folk Festival Of The Blues, a live album where he played behind Muddy and Wolf, as well as singing a couple himself.

At least one listener got what Guy was doing, an English kid named Jeff Beck. “It was discovering Buddy Guy and that album in 1962 that made me realise there was a job there for me to do,” says Beck. “There was a loony there who’d already proved it! He did these frantic solos that told me that I wasn’t alone.” If the album (also known as Live From Big Bill’s Copacabana and Live Action!) ever gets reissued, you’ll hear the entire foundation of Mr Beck’s blues style right there.

By the time label boss Leonard Chess realised that what Buddy had been trying to do was now beginning to sell truckloads of records for the likes of Hendrix, Beck and Clapton, Buddy was out of there and signed to Vanguard Records, where a blues-purist producer insisted Guy continue his Chess style, rather than the full-on house-wrecking of his live shows.

In the wake of the Atlantic debacle came Guy’s wilderness years: the only albums of any merit released by Buddy between the early 1970s and the early 1990s were 1977’s Drinkin’ TNT ‘n’ Smokin’ Dynamite, a Bill Wyman-produced live shot with Junior Wells, and 1981’s Stone Crazy, a hastily recorded one-day-live-in-the-studio item laid down during a break in a European tour. In his 40s and 50s – surely the prime of a bluesman’s life – Buddy’s time was spent either on the road or attempting to run Chicago’s Checkerboard Lounge, his first venture into club management. It’s not known whether his famous friends – Clapton, the Stones, Jeff Beck an’ all – ever made any serious attempts to get him signed up and properly recorded, but their frequent citations of admiration kept successive generations coming along to Buddy’s live shows.

“I’m very proud, but it’s a give-back thing,” says Guy. “I’m very proud to have players of that calibre say stuff like that, because you still have so much of your own. Regardless of what you got from somebody else, you still got a lot of Eric and a lot of Stevie and a lot of Beck there. That’s not all Buddy Guy; they might’ve said ‘I got this from you’, but credit where credit is due. They done played a lot of great music to make themself famous, and they deserves a pat on the back for that.

“Sonny Boy Williamson and them used to make it sound so good: they call it ‘hand-me-down’. You up there with it now; hand it back down here. Hopefully now our blues music will survive, because it had to be handed down. We come and we go, and we leave things. And I just hope that we can leave some of the music that these guys invented and left, and I’m tryin’ to carry on and I just hope someone grab it and keep it goin’. Over the years, some critics and some radio stations and some television stations didn’t give us the same opportunity that everybody else had. They just throwed our music in the back room and closed the door. The late Stevie, Eric, Beck, Robert Cray, Bonnie Raitt axed, ‘Let’s open this back door now, let some of this stuff outta here’, and when it came out some people liked it, and record companies are sayin’, ‘Gee, now why did we do that in the first place?’ See, they will bring Buddy Guy on The Tonight Show, bring him on David Letterman’s show and Saturday Night Live. This is making me feel very proud of the music that I’ve stuck with for all of my life. I’m only good at playin’ what I know.

Buddy Guy was in his mid-50s when his next opportunity sauntered along. He grabbed it with both hands and never let it go. The London-based Silvertone/Jive label released Damn Right I’ve Got The Blues – the first album of his entire career on which he had both a creative free hand and a sensible recording budget – and he’s been cutting for them ever since. 2010’s Grammy-winning Living Proof is the most recent of his dozen or so efforts for them: its opening track proudly proclaims that the singer is 74 Years Young, before the guitar unleashes a burst of fiery fury which would scare the shit out of players a third Buddy’s age.

So now let’s get the man on the phone. It’s just gone 3pm in London and just after 9am In Chicago, but Buddy Guy’s in his office at his nightclub Legends, and ready to talk some blues.

I’ve just finished reading your new book… How do you feel about getting all that stuff down in print after all this time?

As my parents always told me, as far back as I can remember: ‘better late than never’. I never thought somebody would offer me the opportunity to write a book. I been living in Chicago for 55 years. It’s like you go to sleep, and wake up, and all those great blues players I come to Chicago to listen to, they all long gone. Some of the information you get in that book, I guess I might be the only guy who can give you those answers, because they can’t answer for themselves. I knew about David [Ritz], he’s like a computer expert who can punch me in and make me come up with some of those answers I almost forgot about until you ask me. I don’t know how to thank him for coming to me and saying, ‘let’s do one on you’…

When you were starting out, you used to think of yourself as ‘the kid’ coming up behind all the great old ‘real guys’. But now it’s 55 years later, and – apart from BB – you are the Chairman Of The Board now, and it’s up to you to represent.

Like I said, it was like you go to sleep and wake up when they were gone. I cry sometimes, man, because all those guys are missing. I never learned nothing in school. Everything I learned was from their records and from meeting ’em, sittin’ in a bar listening to Muddy Waters sing. I don’t care how good the next person to come along is, there will never be another Muddy Waters or Howlin’ Wolf or Little Walter. That was my schoolin’. I don’t have school sense: I got street sense. I mean, in terms of the music, I never learned nothin’ from books about music. I learned from listening and watching, payin’ attention to these great guys, and I’m so grateful to have gotten here before they passed away and left me alone here. The last thing Muddy Waters told me before he died was, ‘Keep the blues alive and carry on.’

Keith Richards once said that all he wanted written on his tombstone was, ‘He passed it on.’

That’s a good way to put it. And Muddy passed it on to me. I can remember it like it was yesterday and hear it like you talkin’ to me now. I’d hear the phone and it would be Willie Dixon at the studio sayin’, ‘Muddy or Wolf want you to come here now.’ There was a Howlin’ Wolf recording called Killing Floor, and it was early in the morning – earlier than now [shortly after 9am, Chicago time] – that they said, ‘Call Buddy.’ And I went in – they used to record ’em early because they wanted ‘em after they’d finished playin’ until five in the morning in some little joint. And they would get me out of bed, man, and say, ‘Play this rhythm behind Wolf on this song’, and I say, ‘Let me hear what it sound like.’ I hear it and just say, ‘I got it.’ Someone asked me what were my favourite moments… I said, I don’t care if I got a gold record, I don’t care if I got an award or nothin’. I was just on top of the world when one of those guys call me and tell me to come play with ’em.

In the book you say that in those days there were two Buddy Guys: the wild man on the stage and the quiet total professional in the studio.

That’s true! In those days the jazz and blues cats would use a lot of profane language, and everybody was an MF, if you know what I’m talkin’ about, and the Chess brothers was certainly an MF. I was learnin’. You can’t learn if you’re runnin’ your mouth the whole time, so I was quiet, to listen and figure out what everybody was doin’. I would just sit back in the corner and listen. When they call me to come make a record, they might say, ‘You playin’ a little too much’ or ‘Pay attention’ or somethin’. I was so excited to be in the studio with ’em, man, it was like I was in heaven. I come to Chicago lookin’ for a regular job, workin’ in a college or pumpin’ gas or doin’ whatever I could to help my family back in Louisiana, my mother and brothers and sisters, and here I was in the studio with Muddy Waters, man! What more could you ask for at 21 or 22 years old?

- Whose version of Little Red Rooster is better: Howlin' Wolf's or the Stones'?

- Willie Dixon: I Am The Blues

- Buyer's Guide: Muddy Waters

- Buddy Guy: 50 Years Of Cool

Well, you could’ve asked to get paid…

[Laughter] Well, they wasn’t doin’ too much of that! You hardly got paid for playin’ the clubs back in those days. All you got was maybe a good-lookin’ woman to come home with you and a good shot of whisky, and I didn’t hardly drink when I first come here. That was your pay! It pays off if you finally be successful, because if you get fame overnight, you don’t know how to handle it. I know guys, man, younger than me, who had a hit record overnight, and they forgot who I was. We had ate a hot dog together, shared a piece of bacon together, and then they come in and ask me who I was. The way I came up, I don’t forget. That’s something about Buddy Guy: I don’t dislike nobody. I don’t care if you big, small, black, white, green or yellow… I love you, man. I can’t dislike you. Even if you do somethin’ to me, man, I’ll walk away so I can keep from dislikin’ you. If the world could be like I am, we wouldn’t have no trouble nowhere.

Amen to that. How was it for you when you heard the British guys who’d been listening to you were playing? Did you think that these cats were doing what you wanted to do but Chess wouldn’t let you?

I came to the UK in February of 1965 and toured with The Yardbirds. Rod Stewart was my valet! Beck and Clapton told me that they’d slept in a van to come and see me play, and that they did not know you could play blues on a Stratocaster ’til they saw me. I said, ‘Man, you jokin’!’ But, to answer your question, no… Chess wouldn’t let me do it, but when Chess found out that Beck and Clapton and Hendrix was pumpin’ it out like I was trying to get them to let me do in the Chess studio… [Len Chess’s] son Marshall heard it and wanted me to do it, but they wouldn’t even let him let me do it. They were sayin’ it wasn’t nothin’ but noise! ‘Ain’t nobody gonna wanna hear that!’

After they heard the British guys doin’ it, they sent Willie Dixon to ‘go get him… he’d been tryin’ to give us that but we let it alone because we was too dumb to hear what he was tryin’ to give us.’ To be honest with you, those guys I was speakin’ of – Clapton, Beck and the other guitarists – they helped us the most, more than any record company. They brought it back here. When the Stones came here, there was a television show called Shindig!, and they wanted the Stones, but the Stones said they’d only come if they could bring Howlin’ Wolf. Mick Jagger said, ‘You mean you don’t know who Muddy Waters is? We named ourselves after one of his records!’

It wasn’t until the early ‘90s that you started getting recorded the way you’d always sounded live, and as soon as you got your real sound on record, your records started selling…

Well, man, I got to tell you, the British guys were it! It was a British guy who made that happen, man, Andrew Lauder from Silvertone Records. Eric Clapton invited me to the Royal Albert Hall. I didn’t have a contract at that time, because all the record companies here [in the US] had given up on me, and he said, ‘I want to sign you, bring you to England to record and let you do whatever!’ And I said, ‘Tell me when!’

He flew in, came to my club and signed me up, and I flew to England and recorded Damn Right I Got The Blues. I was sayin’ to myself maybe I ought to do like Hendrix, because the British was sayin’, ‘Bring it on, man!’ They wasn’t sayin’ that it was too loud or didn’t sound right.

Let me give you an example: in 1962 Chris Barber, the trombone player, brought Muddy to England, and he came over and played the slide guitar with the amplifier and the British booed him. Chris brought him back the next year and Muddy left his amplifier at home and played acoustic and they booed him again! They said, ‘You introduced us to the electric guitar with that slide and we want that!’ And that’s why we love the British, man, because they the ones who woke America up and said, ‘They had it, they didn’t want it, we want it and we gonna show ya how good it is.’ We love you guys.

I interviewed Muddy, and he said, ‘It took the British to hip my own white people to what I was doin’.’

That’s the truth. Couldn’t be said better. It took the British to help us all: BB King, Ike & Tina Turner, Big Joe Williams… All those guys. It took the British to let America know who we were.

I want to get the Buddy Guy point-of-view on the current state of the blues. You’re out there, working all over the US and all over the world… where’s the blues at right now?

It’s kinda scary right now… I’m currently producing a little kid. He turned 13 last month. Remember the name: Quinn Sullivan. He just opened a show for me a couple of nights ago. I put the CD out myself: it’s called Cyclone. If you listen to it, you’re gonna want to interview this kid, because there ain’t a way in the world a kid that age can play like he play, man. He’s playing Eric Clapton, Jeff Beck, me, BB King and God knows who else. I really want you to hear this, man, because I’m tryin’ to get him out there.

I remember both Derek Trucks and Joe Bonamassa started out as kids…

Well, this kid was playing like this at seven years old, and I told his dad when I saw him that I’d do anything I could to get him out there. I introduced him to Eric a little over a month ago, to Ronnie Wood and I think I introduced him to Mick, too. This kid is playing like somebody my age, he don’t sound like he’s 13 years old. When I first saw him, I said, ‘Well, come on up here and play your tune for a minute or two’. But the kid matched me note for note for a whole hour. His dad said, ‘You see that? He got that from you’, and I said, ‘I don’t think so… I think he had it all the time.’ So what my British friends did for us in America, saying ‘you had it all the time’… That’s what the Stones and all them said to America. ‘You had it all the time. You just didn’t know you had it.’ Speaking about BB, Muddy and all the guys.

How’s the blues scene in general?

Well, I just came in last night [from a tour] and each place I played was sold out. That lets you know that somebody is still likin’ the blues. My worry is, the blues is not being played on the air any more. They don’t play the blues on the radio like they did 50 years ago.

We had AM radio in the States: you could hear spirituals, jazz, you could hear Muddy Waters. Now you hear the same record all day, and they don’t give other people a chance. And I’m not just talking about Buddy Guy. That’s what scares me about the blues.

You ain’t gonna go in the record store and buy somethin’ you never heard of. You ain’t gonna say, ‘Give me Quinn Sullivan’, because he’s not out there yet, and I’m tryin’ to put him out there.

Well, it’s like you say in the book: you can’t kill the blues. You can drive it underground, but it always comes back.

It’s been like that my whole life. But why treat the blues the way you treat it? Same with jazz: you don’t really hear jazz on the radio no more. Blues is ignored a lot, man: we don’t get the publicity on blues that other musics do. Once I thought the lyrics we were singin’ was a little strong for the young generation of people, but when hip-hop came out, it was much stronger than what we sang about. It’s something else, one more reason why we don’t play blues now the way we did. We got to get the music out there, we got to get it exposed to the young people, and I think the blues will survive a little longer.

And Buddy Guy will be right there with it – we devoutly hope – for a good many long years to come. It only remains to add that if you’re ever travelling through Chicago, drop by Legends. If you’re lucky, Buddy himself might be on stage… And if you’re luckier still, he might be in the kitchen. The second most important thing in Buddy’s life, after his music, is cooking. “My whole family is chefs,” he’ll tell you, laughing… And if his cooking is as cookin’ as his music, your palate will be as tickled as your ears.

“Buddy Guy is a copycat.” His words, not mine. Yet no matter how assiduously he may mimic Muddy Waters or BB King (or Wilson Pickett, or John Lee Hooker), he is so hugely and quixotically himself that it always comes out sounding exactly like Buddy Guy. He’s a man who’s spent his whole life thinking of himself as a follower, and now that the mantle of leadership has fallen onto his shoulders, he’s not entirely comfortable with it. He wears it as lightly as he can, but nevertheless he wears it well.