Bullets, bikers and burnout: the story of Jimi Hendrix's last gig

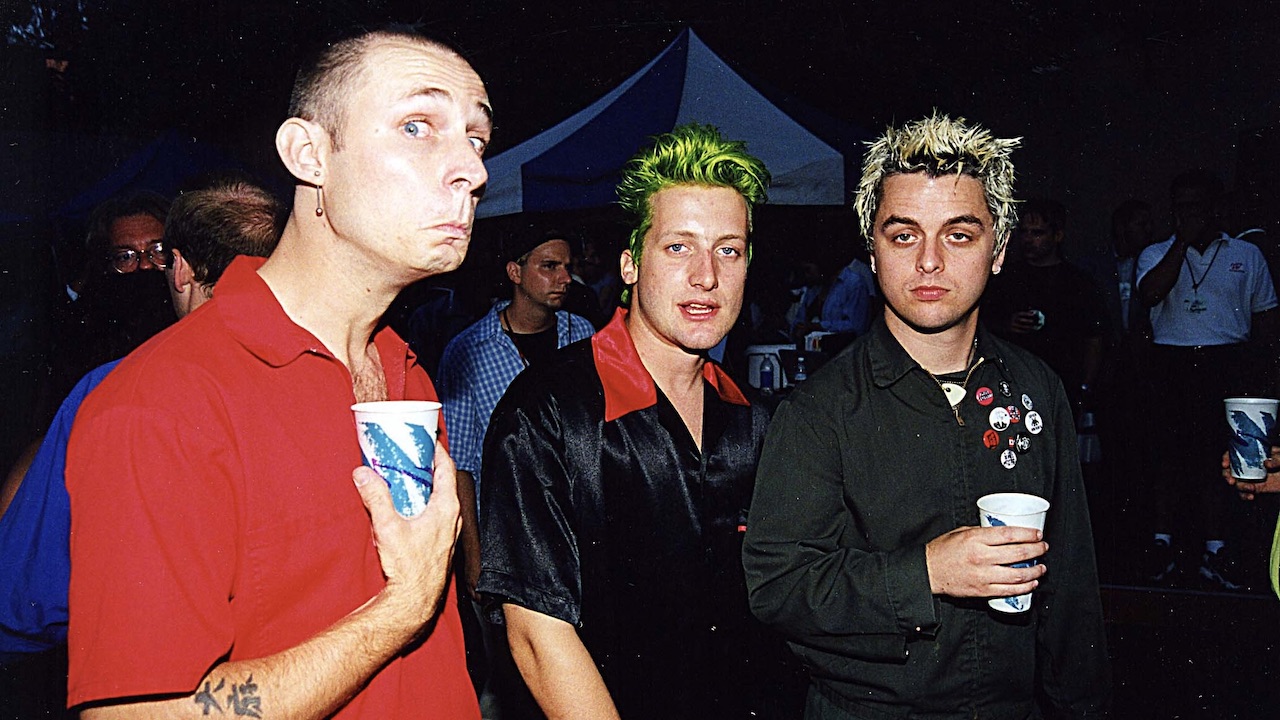

Jimi Hendrix's final show was at a festival marred by terrible weather, machine-gun fire and marauding Hell's Angels

“If I’m free, it’s because I’m always running” – Jimi Hendrix interviewed in The Times, Sept. 5, 1970.

On September 5, 1970, the day before he played his last ever gig, UK music paper Melody Maker published an interview with Jimi Hendrix.

“It’s all turned full circle,” Jimi told interviewer Roy Hollingworth, “I’m back right now to where I started. I’ve given this era of music everything. I still sound the same, my music’s still the same, and I can’t think of anything new to add to it in its present state… When the last American tour finished earlier this year, I just wanted to go away a while and forget everything. I wanted to just do recording, and see if I could write something. Then I started thinking. Thinking about the future. Thinking that this era of music – sparked off by The Beatles – had come to an end…”

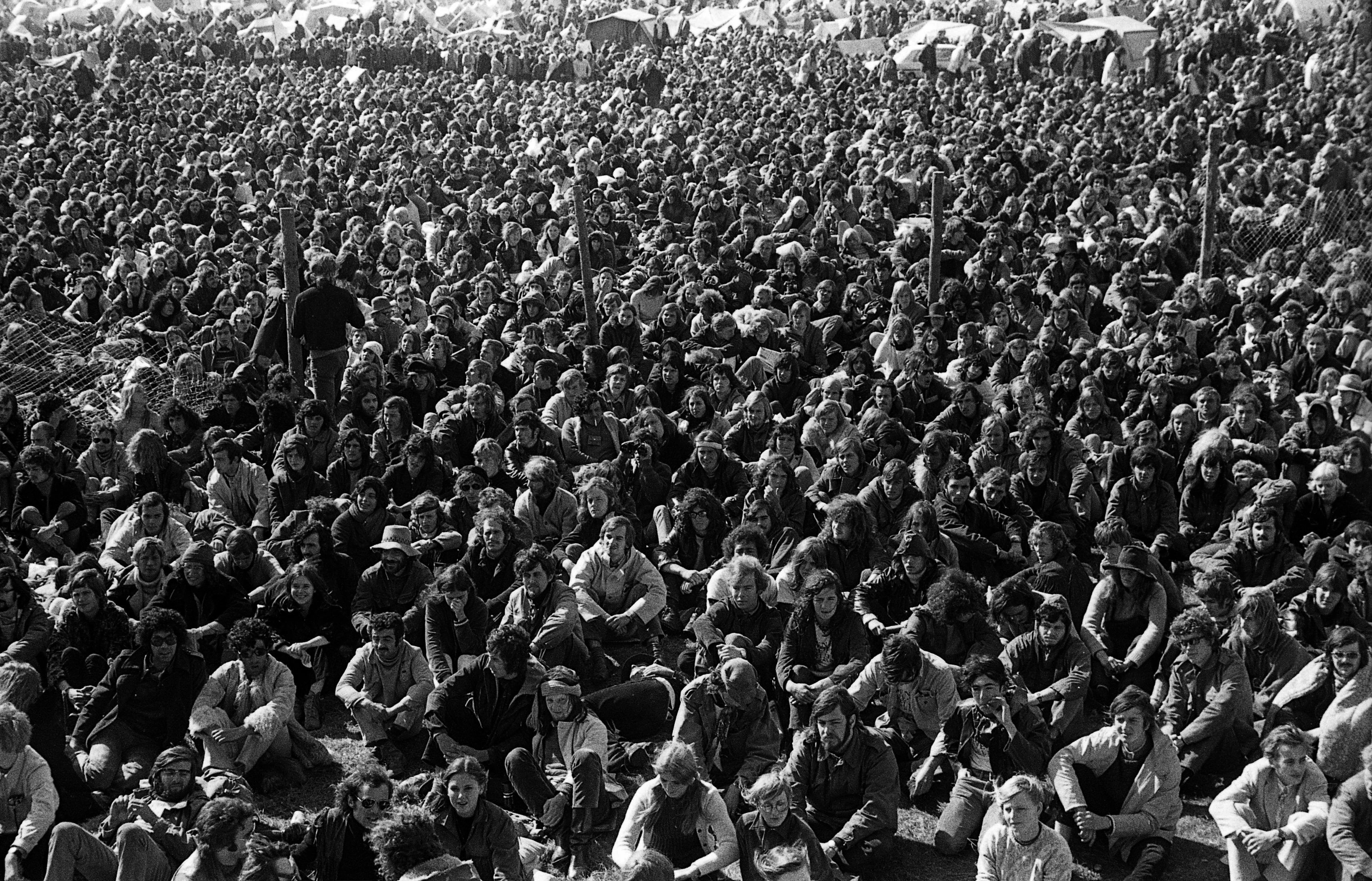

The interview had taken place some days earlier: on August 29, the day before Jimi played the Isle Of Wight Festival, an appearance that marked the first day of a week of intensive touring. Over the next seven days, Hendrix, bassist Billy Cox and drummer Mitch Mitchell would play six major gigs in three countries across Europe.

They would have done more too, but the tour was cut short after concerns for the health of Cox: on September 1, someone had spiked his drink with LSD and he was still paranoid and exhausted over a week later. On September 9, the tour was cancelled and Cox returned to the States. Little did they realise at the time, but they’d already played their last gig together.

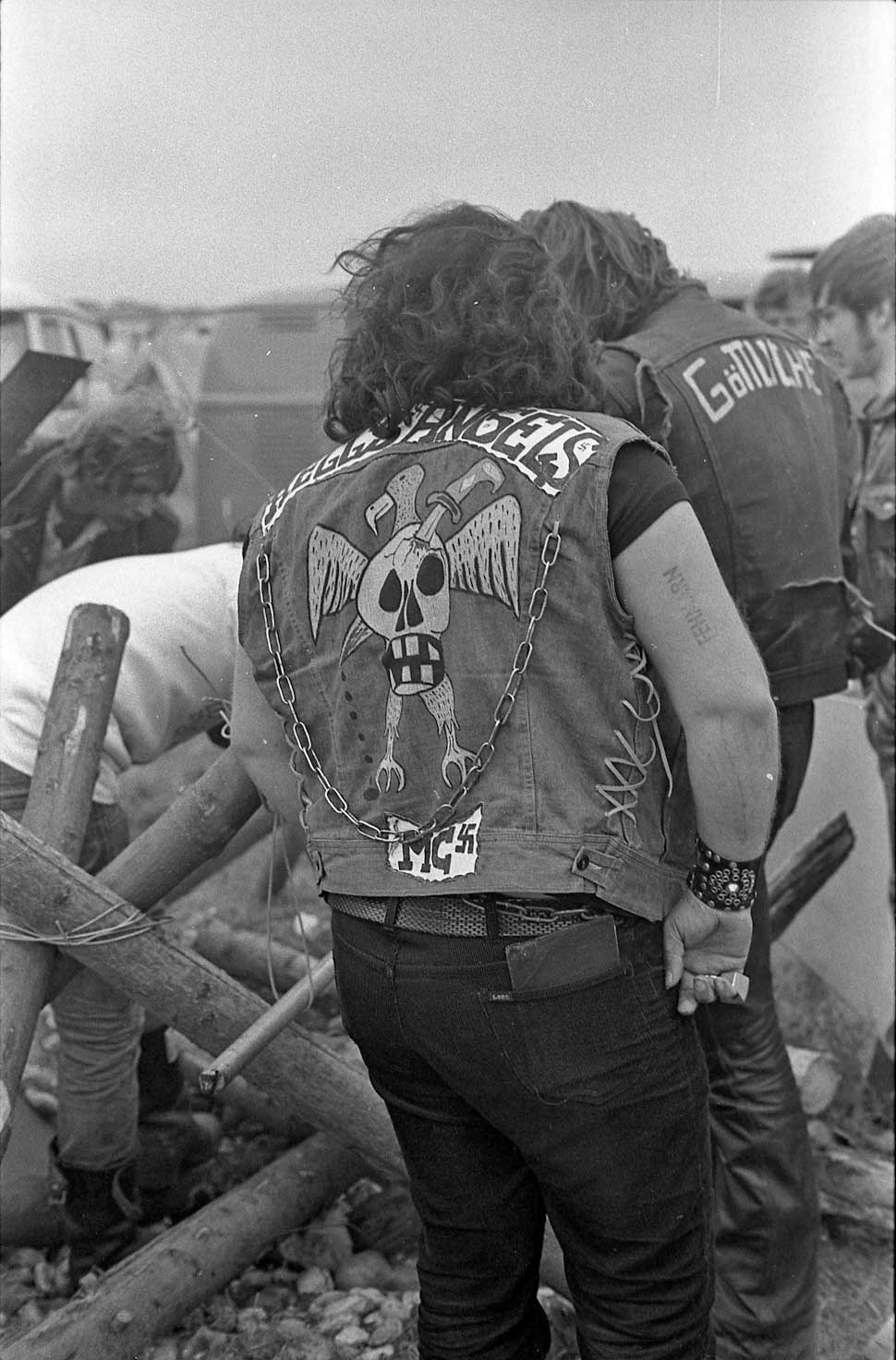

The ‘Love + Peace Festival’ on the Isle of Fehmarn, off the coast of northern Germany in the Baltic Sea, was intended to be the European answer to Woodstock. Instead, it turned into a mini-Altamont. Over-run by a German biker gang, battered by storms, plagued by cancellations from big-name acts like Emerson, Lake And Palmer, the festival was descending into chaos, violence and arson by the time Hendrix got there on September 6 for his last live performance.

From his position onstage, UK student-turned-stagehand David Butcher was relatively sheltered from the chaos. But he knew something was wrong.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

”On the second day this English guy who was manager of one of the other bands decided to pull out,” remembers Butcher. “The Hell’s Angels were causing so much trouble – they were ransacking the office and giving free tickets to everybody. They weren’t in charge of security, but basically they kind of took over and there was a lot of trouble, including gunfire. Machine-gun fire. For a while afterwards I wondered if we’d imagined it. But it was real.”

David Butcher’s road to Fehmarn was a happy one filled with cheeky blags and happy coincidences. A student at Keele University (where he was social secretary of the student union and responsible for booking bands), he was also a Hendrix nut. “I’d been a huge fan, right from the first time I heard Hey Joe. When I was at university, Electric Ladyland came out and I just used to listen to it every day. I still think that Voodoo Child – the long version with Stevie Winwood and Jack Casady – is one of the most amazing pieces of rock music ever.”

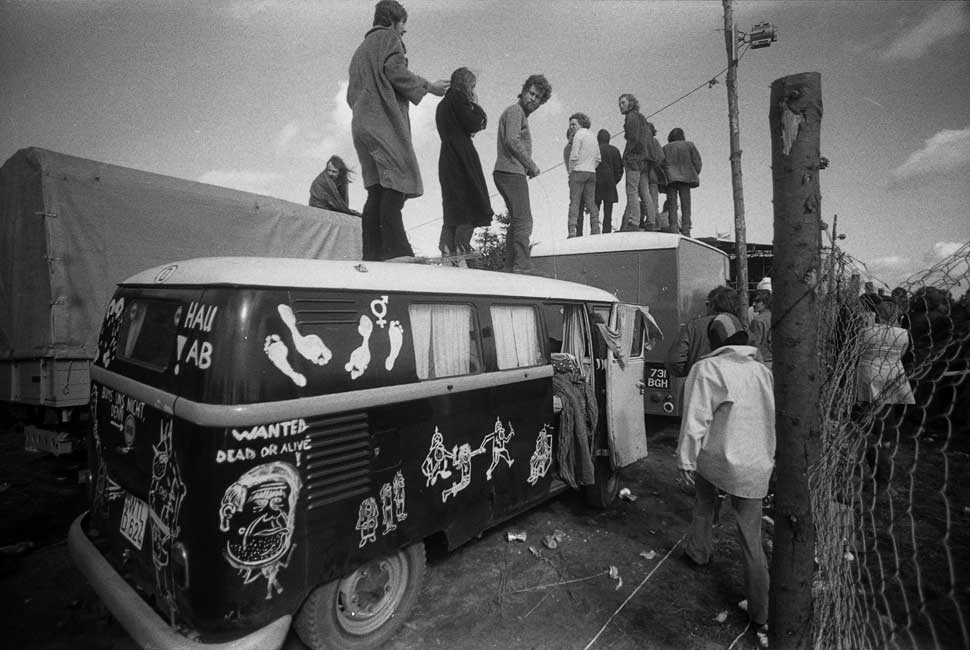

In the summer of 1970, David and his friend Dave Philip travelled to Düsseldorf where Philip’s father was stationed in the army. With his parents away, the two made full use of the house and the times. ”We were just hanging out there, getting herbally enhanced, when we saw a poster for this festival in Fehmarn. We didn’t have any money so we sat down at this typewriter and we concocted this letter to the festival organisers saying that we were passionate about music – which was true – and that we were doing a thesis on music as a unifying force and visiting loads of festivals…”

They fell for it: a few days later, a couple of backstage passes arrived in the post. The two hitchhiked all the way up to Fehmarn. “We got there the night before, on the third of September. We were absolutely exhausted. It was really cold and wet, and we’d been hitchhiking for a day and half, and we just found a spot on the grass to lie down, got into our sleeping bags and crashed out. In the morning we woke up, and we were surrounded by cars! We’d crashed out in what was the middle of the car park area and during the night hundreds of cars had appeared around us…”

Jimi’s journey to Fehmarn hadn’t been filled with as much good fortune. Hendrix hadn’t wanted to come to Europe in the first place, but manager Michael Jeffrey had convinced him that his new Electric Lady studios needed an injection of cash – the answer was a short tour that began at the Isle of Wight festival and continued in Denmark, Sweden and Germany.

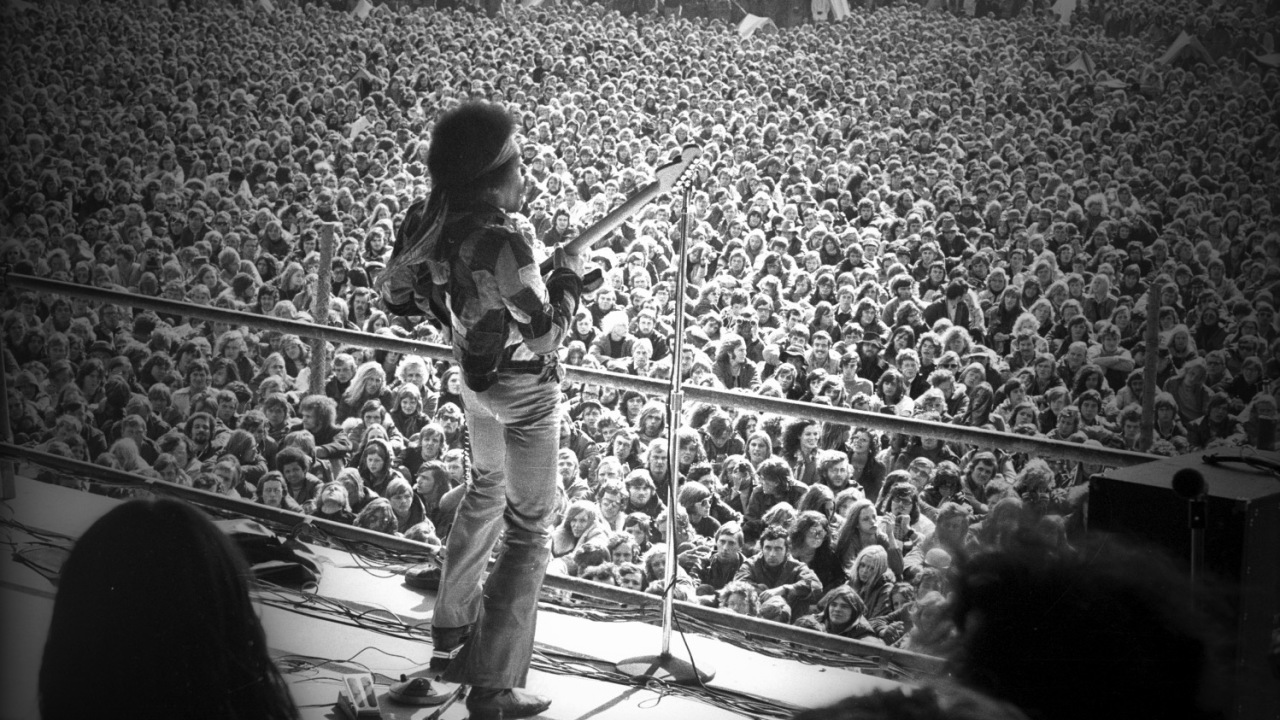

Jimi arrived in London on August 27, conducting a string of interviews, before heading to the organised chaos that was Isle of Wight and probably the largest single audience of his career. Around half a million people witnessed him struggling with technical problems (the amps picking up radio signals), the effects of a cold, exhaustion (the band didn’t actually appear onstage until 2am on Monday 31) and whatever combination of drugs and alcohol he was juggling at the time.

Less than 24 hours later they were playing a gig at an amusement park in Stockholm, Sweden, with Jimi insulting an audience crying out for the hits (“Fuck you, fuck you – come up and play guitar”) and appearing weary with the whole process (“Ah, let me tune my guitar there again – oh, what the hell, you don’t want to know…”).

The Swedish promoter had allegedly demanded that Hendrix play for no more than an hour so that the audience could use the nearby fun fair, claiming that he’d make more money from the fair than the gig. Justifiably offended – and apparently leaving the stage at one point to argue with the promoter – Jimi got his revenge by playing for 110 minutes.

“This song is dedicated to all the girls who get laid,” he said before the final track, Foxey Lady, evidently enjoying himself. “And, em, all the little girls back there with those little yellow, orange, pink and turquoise panties that they keep throwing on the stage. It’s close to Mother’s Day – anybody that wanna be a mother, come backstage.”

The next day, the band – billed everywhere as the Jimi Hendrix Experience, something that Hendrix seemed to have given up fighting – travelled to Gothenburg for an outdoor gig. During the day he gave an interview to a Swedish newspaper who asked him about a contribution he had made to ‘the Martin Luther King Memorial Fund’.

“Would you rather I gave it to the Ku Klux Klan?” asked Jimi. “In the USA you have to decide which side you’re on. You’re either a rebel or like Frank Sinatra.” His idealism questioned by the straights, his commitment questioned by his audiences, he felt exhausted. “I’m tired of lying down and I feel mentally hollowed,” he told the interviewer.

If the gig that night was better than the previous one, it still wasn’t enough to impress a visiting Chas Chandler – the man who had managed Hendrix to stardom but parted ways with him the year before.

“He was wrecked,” Chandler said. “He’d start a song, get into the solo section and then he wouldn’t even remember what song they were playing at the time. It was really awful to watch.”

I’m not sure I’ll live to be 28 years old. I have nothing more to give musically. I will not be around on this planet any more, unless I have a wife and children – otherwise I’ve got nothing to live for.

Jimi Hendrix, days before his death

At a party after the gig, Billy Cox’s drink was spiked and the drug-free bass player experienced a nightmarish bad trip that, combined with the stress of a busy schedule, over the next few days put him close to a nervous breakdown.

The whole camp was at the end of its tether. “I’m not sure I’ll live to be 28 years old,” Jimi told an interviewer the next day. “I mean, at the moment I feel I have nothing more to give musically. I will not be around on this planet any more, unless I have a wife and children – otherwise I’ve got nothing to live for.”

With Jimi in the grip of a feverish cold, that night the band played in Arhus, Denmark, cutting short his set after only three numbers (he had only ever stopped a gig once before: at the last Band Of Gypsys performance at Madison Square Garden in January that year).

A girlfriend, Kirsten Nefer, recalled that when she met him earlier that day he was “staggering” and “acting in a funny way”, telling her, “I don’t want you to see me like this”. Nefer says that Jimi was unable to even tune his guitar before going onstage. Helped on to the stage by roadies, he was escorted off again minutes later, Mitch Mitchell covering his exit with a long drum solo.

Backstage, the venue’s manager, Otto Fewser, claimed that “Hendrix collapsed into my arms and we sat him upon a chair. He was cold – cold fever – then they asked for cocaine. ‘We have not cocaine,’ I say. Hendrix could not play more.”

The gig cancelled, Hendrix headed back to his hotel where he spoke once again to Anne Bjorndal, a journalist who had interviewed him earlier.

”I love reading fairy tales,” he told her. “Hans Christian Andersen and Winnie The Pooh. Fairy tales are full of fantasy and they appeal to your imagination.”

Bjorndal claims that Jimi then started crawling around, ‘acting out’ Winnie The Pooh. “Winnie The Pooh is searching,” she quoted him as saying. “It’s winter and the tracks are easy to follow and, oh, now the seasons have changed. I’ve lost the track…”

Interviewer: How do you get your inspiration?

Jimi Hendrix: Pardon – say it again?

I: How do you get your inspiration?

JH: From the people.

– August 30, Isle of Wight

In the very early morning of September 3, Mitch Mitchell got a phone call telling him that his wife had given birth to a baby girl. Mitchell chartered a flight back to London, taking Billy Cox with him, meeting up with Jimi later that day in Copenhagen for a blistering gig at the city’s KB Hallen hall. Over the worst of his cold, Hendrix had spent the day with Nefer at her parents’ house and hit the stage apparently invigorated.

In a review of the concert, Danish newspaper Politiken raved: ‘Jimi was tired and ill in Arhus, but was so high in Copenhagen that this was true energy, true adrenaline which ran through his fingers, through the guitar and into all of us… As a warrior of love, he stood dressed in many colours and was the best guitarist rock’n’roll music can offer.’

The band then flew on to Berlin to perform at the Super Concert ’70, an indoor festival at the city’s Deutschlandhalle with Procol Harum, Ten Years After, Canned Heat and more. Interviewed by American Forces radio before the gig, he was asked if he ever thought there would ever be a festival as successful as Woodstock.

”Well, I don’t know,” said Jimi. “It’s pretty hard for this sound to get to all those people in such a big crowd. Like, if we had smaller crowds you can really get next to ’em more, you know?” How did he feel about playing in front of 400,000 people? “That’s what I mean,” he said. “It’s just too big. You know you’re not getting through to all of them…”

We were supposed to be on at eight. By about six we heard this wind and then it turned into a gale. We knew by then there were other problems as well: the usual equipment trouble plus Hell’s Angels with guns...

Mitch Mitchell

After a strong performance in Berlin, the band flew to Hamburg, then caught a train to Grossenbrode in the north. On the train, Jimi wanted to lie down so he broke into a locked sleeper car.

“The guard freaked out and stopped the train and threatened to throw us off,” remembered tour manager Gerry Stickells. The situation was smoothed over and the band arrived on Fehmarn on the Saturday afternoon.

“We got there mid-afternoon,” said Mitch Mitchell, “and were supposed to be on at eight. By about six we heard this wind and then it turned into a gale. We knew by then there were other problems as well. The usual equipment trouble plus Hell’s Angels with guns.”

Promoters Christian Berthold, Helmut Ferdinand and Timm Sievers had timed their event to coincide with the Isle of Wight festival (with the aim of snagging some major acts, including Hendrix, then at the height of his popularity in Germany after his appearance in the Woodstock movie) – but they hadn’t counted on some of the same elements that had disrupted the UK festival to derail theirs: rogue bikers, overcrowding, bad weather and a load of cancellations had soured the ‘Love + Peace’ attitude of the 30,000-strong crowd.

“If you think the Isle of Wight was a mess, you should have been to Fehmarn,” comments Ford Crull. Now a New York-based artist, Crull was 17 at the time and had heard about Fehmarn while at the Isle Of Wight.

“I was on my way to Sweden to meet a girl I’d met,” he says. En route he took a detour, hooked up with British folk rockers Fotheringay (Sandy Denny’s band after Fairport Convention) and found himself hired as a stage hand and enjoying a bill that included The Faces, Sly & The Family Stone, Cactus, Procol Harum, Ginger Baker’s Air Force and more.

“Fehmarn had a good line-up, but it was just chaos,” says Crull today. “Sandy Denny kept getting an electric shock from the mic. Whoever built the stage was an idiot. There were gales, so the sea just kept blowing on stage. The whole place was wet and so she kept getting shocks.”

Crull remembers another potentially dangerous experience as he accompanied Rod Stewart and the stage manager over to the business office to collect their payment.

“They just had suitcases packed with cash to give the bands – in American dollars too,” he says. “We had to walk back through everyone with these cases packed with I don’t know how many thousands of dollars. I’m sure if the bikers had known, they would have stormed the office.” (That wasn’t the only excess. Back in The Faces’ camp, Crull pulled out his lump of hash. The Faces pulled out theirs. “I had an ounce,” he chuckles. “They must have had a pound.”)

David Butcher had also been hired as stage hand. “One of the managers of a number of the English bands including Fotheringay, I think, had paid us to be stage hands,” he says. “We were just there and we seemed keen and we spoke English and he said ‘Can you help us out?’ All we had to do was help the roadies and made sure there weren’t too many hangers-on. It was one of those revolving stages so the challenge was, when the guys came up and got on to the backstage bit, they needed peace and quiet and space so they could tune up. We got drinks – anything that was needed.

Whoever built the stage was an idiot. There were gales, so the sea just kept blowing on stage. The whole place was wet and so Sandy Denny kept getting shocks.

Ford Crull, stage hand

“We were getting paid the equivalent of £12 a day, including food and wine, so this being 1970 we were doing pretty well. On day two of the festival, this guy who’d employed us appeared in the late afternoon. He had a huge wad of German marks and he said, ‘Listen you guys – I’ve got the cash for the bands that have played. I’ve got a couple of bands that are due to play later, but I’m taking them home cos this thing is falling apart. The Angels are just ruining the whole thing. The cash isn’t there – I’m outta here.’

“He said, ‘What are you guys doing? Are you staying on?’ I said, ‘Yeah – I’m staying on because of Hendrix.’ He said, ‘Well, that’s up to you – my advice is don’t stay because it’s getting dangerous. But if you’re staying, you can take over. Do you want to be stage manager?’ So I said ‘Yes’, and he got out his stage manager pass and stuck it on me. And that was that. We’d gone from nowhere to getting free press passes, then backstage passes, then all of a sudden I was stage manager – whatever that meant.”

Hendrix was due to take the stage at 8pm but when Gerry Stickells visited the site, a force five gale and torrential rain convinced him that it would be a big mistake. Instead Jimi stayed where he was in the Hotel Dania in Puttgarden on the north of the island. Home to most of the musicians appearing at the festival, the bar was drunk dry.

David Butcher ended up there too: “My memory’s hazy, for good reason – but we landed up in this bedroom and there were people everywhere, just crashed out. Alvin Lee of Ten Years After was in there. Someone had a pair of bongos and there was lots of marijuana going around. I just remember feeling very mellow and Alvin Lee was strumming away and someone was playing bongos and someone was singing – and we just fell asleep where we were.”

Billy Cox wasn’t having nearly as good a time of it. “Billy had kind of a breakdown,” Gerry Stickles told Tony Brown for his 1997 book, The Final Days Of Jimi Hendrix (published by Omnibus, but now out of print). “It was part of my job to nurse him through it, to get the date over with. But he was severely paranoid about what was going on, you know. This whole thing was going to collapse and everybody was going to be killed and God knows what else.

"I had to sit on the side of the stage and stuff like that, so he could see me all the time. Everybody was feeling bad at that time. When somebody’s like that, it permeates through the whole thing. But this was the last show – ‘let’s just do it, get it over with and get out of here’ – and that’s what happened.”

“I’m tired. Not physically. Mentally. I’m going to grow my hair back, it’s something to hide behind. No, not to hide. I think I may grow it long because my daddy used to cut it like a skinned chicken”

– Jimi Hendrix, The Times, September 5, 1970.

The following morning, the band arrived on site by 11am, having been rescheduled for midday. No sooner had they got there than Stickells was hit on the head by a plank of wood with six inch nails in it. Considering the tensions, the band posed for German photographer Gernot Piltz, Jimi even rolling around and laughing on the grass backstage.

“Maybe that was before he realised the situation there, ” says Ford Crull. “When I saw them, Jimi and Mitchell and Cox weren’t even talking to each other. And he and Mitchell were so skinny. Mitchell’s legs were as thin as my arms.”

It was David Butcher’s job to make sure that the band were taken care of. “I didn’t really pick up on the turmoil that was obviously going on,” says Butcher. “Jimi seemed pretty relaxed. He was probably stoned a bit before he arrived. There were one or two joints being passed around. Very friendly, gentle guy – really nice guy. So laid back and sensitive…

I don’t give a fuck if you boo, as long as you boo in tune, you mothers…

Jimi Hendrix

"They had one or two caravans at the back where the stars stayed for the hour or so before they went on. We made sure he was okay and settled in the caravan, then we went back to the stage and made sure the roadies had everything they needed. Later he came out of the caravan and came backstage and then we kept everyone away so that he could tune up and practice.”

Butcher seized the opportunity to introduce himself as social secretary for Keele University and ask Jimi if he’d come and play there. “Sure – talk to Gerry Stickells about it,” said Hendrix. At around one o’clock in the afternoon the Experience took to the stage to boos and jeers and shouts of “Hau ab!” (German for “go home” or “get lost”).

Captured on an ‘official bootleg’ release from Experience Hendrix’s Dagger Records imprint (Live At The Isle Of Fehmarn), Jimi takes it in his stride, being first gracious (“Peace anyway, peace,” are his first words), then comical (joining in with the booing), before confronting the crowd. A rare video clip of the festival on YouTube shows Jimi walking to the mic, arms outstretched: “I don’t give a fuck if you boo,” he shrugs, “as long as you boo in tune, you mothers…”

The booing ceases and he then placates them by introducing the band and adding, “We’d like to play some music for you and, er, we hope you can dig it. Because we’re sorry we couldn’t come on last night, but it’s just unbearable man. We couldn’t make it together like that, you know.”

From there, the band launch into Howlin’ Wolf’s Killing Floor. With amazing symmetry, this was the opening song of the Jimi Hendrix Experience’s first ever gig, on October 18, 1966, in Paris. At the end of the song, there was a big cheer and no more boos – the audience are already won over. Then it was Spanish Castle Magic and into All Along The Watchtower. David Butcher was standing at the side of the stage when he was given one more responsibility. “The guy who was controlling the sound took a break, so I was sort of delegated to look after the sound – but hopefully just stand there and not do anything, cos I didn’t understand [how to work the mixing desk].

“He was halfway through All Along The Watchtower when he looked round at me. He’s doing this great solo and then he does that amazing thing where he stops playing with his left hand – he’s just got his right hand on the frets and the solo is magically continuing, y’know – and I’m sort of mesmerised by this when I realise he’s looking at me. He’s walking towards me and he’s saying, ‘More drums, man’. So there I am, trying to find the right fader… It was a wonderful moment because I did actually find the right levers and just moved them up a bit and he kind of smiled and winked, so I obviously did the right thing…”

From there it was Hey Joe, Hey Baby (New Rising Sun), Message To Love and Foxey Lady. As the band played the next number, Red House, the weather turned again. Umbrellas went up and people huddled under tarpaulins. Jimi laughed and improvised lyrics: “Yeah, well I got a bad, bad feeling,” he sang before laughing: “Yeah, the weather is telling you something.”

“It was cold and it was raining, with a very cold wind,” remembers Butcher. “The rain was coming in and he was standing there, risking being electrocuted but just carrying on, you know? He didn’t move back from the front of the stage, he just carried on. It was quite amazing, really.”

But the trouble wasn’t over. “From my position onstage I could see fights breaking out as Jimi approached the end of his set,” says Butcher. “I’m sure Jimi saw them too, but he was powerless to do anything about it.”

When the rioting started, the German police appeared and they basically had a gun fight with the the Hell's Angels.

Ford Crull, stage hand

The last two songs Hendrix ever played live were Purple Haze and a suitably stormy version of Voodoo Child (Slight Return). Fittingly, coincidentally, ironically, the final lines of the song – and the final lines that Hendrix would ever sing in public – are as follows: ‘If I don’t see you no more in this world/I’ll meet you in the next one and don’t be late, don’t be late.’

“Thank you. Goodbye. Peace!” shouted Jimi. David Butcher escorted them down the wooden steps at the back of the stage, and they got in a helicopter bound for Hamburg.

Butcher decided it was time for him to leave too. “We weren’t expecting to be paid anything for the final day, so we were gone. We had a good supply of marijuana. All this stuff was on sale – they had guys from Holland out in the crowd, with everything set out on a table, clearly labelled – ‘Whatever you wanna try, try’. There were no police at all. I suppose it was on an island and they just thought, ‘Let them get on with it’. By the time we left the Angels were rampaging the stage, just tearing everything down, just dismantling everything.”

Ford Crull was in the thick of it. He and one of Fotheringay’s roadies commandeered a van and piled the band’s gear inside. “The bikers realised they weren’t gonna get paid and they were running amuck. When the rioting started, the German police appeared and they basically had a gun fight with these guys. Our van had the windows smashed and I held up a tarpaulin so he could see while the rains came blasting in. When we got to the hotel where the band was Sandy Denny gave me a big kiss for saving their stuff and they offered me a job. She was a real angel.”

As Hendrix left the site, a German anarchist rock band called Ton Steine Scherben took to the stage. Infamous in Germany for songs like Keine Macht Für Niemand (No Power For No One) and Macht Kaputt Was Euch Kaputt Macht (Destroy What Destroys You), the appearance only added to their infamy: as they played, the stage went up in flames. To some in the audience it looked like Ton Steine Scherben had lit the match, giving them even more underground cred.

The era of Love + Peace was truly at an end. Less than two weeks later, on September 18 – two months short of his 28th birthday – Jimi Hendrix was dead. A week or so after the festival, David Butcher was “in an agent’s office somewhere in Kensington”, telling him about the conversation he’d had with Jimi about playing at Keele. “This guy was saying how he could liaise with Jimi’s agent and make it happen. And it was at that moment that the door opened and the secretary walked in, in tears, telling us that he’d died."

If the chaos of the preceding weeks made his death seem almost inevitable, Hendrix wasn’t weary of life – just life in the Experience.

“A lot us hung out at night by the campfires backstage at Isle of Wight,” says Ford Crull. “Jimi and Miles Davis were around one, talking about working together – my friend heard them. Jimi wanted to be taken seriously as a musician, he didn’t want to play the guitar with his teeth… I think his handlers were almost forcing him to cash in, and he wanted off.”

Certainly Hendrix had been optimistic just days before, telling the Melody Maker, “Something new has got to come and Jimi Hendrix will be there. I want a big band. I don’t mean three harps and 14 violins, I mean a big band full of competent musicians that I can conduct and write for. And with the music we will paint pictures of earth and space, so that the listener can be taken somewhere…They are getting their minds ready now. Like me, they are going back home, getting fat and making themselves ready for the next trip.”

He never made it.

Thanks to David Butcher and Ford Crull. Many of the quotes used in this piece were collected in Tony Brown’s The Last Days Of Jimi Hendrix – thanks to Steve Jackson and Chris Charlesworth of Omnibus Press.

Postscript: Famously Jimi jammed with Eric Burdon on the night of his death, playing guitar on a couple of song at Ronnie Scott’s. But he didn’t sing, play any of his own numbers, nor was he on the bill. The Fehmarn festival was his last scheduled performance.

Scott is the Content Director of Music at Future plc, responsible for the editorial strategy of online and print brands like Louder, Classic Rock, Metal Hammer, Prog, Guitarist, Guitar World, Guitar Player, Total Guitar etc. He was Editor in Chief of Classic Rock magazine for 10 years and Editor of Total Guitar for 4 years and has contributed to The Big Issue, Esquire and more. Scott wrote chapters for two of legendary sleeve designer Storm Thorgerson's books (For The Love Of Vinyl, 2009, and Gathering Storm, 2015). He regularly appears on Classic Rock’s podcast, The 20 Million Club, and was the writer/researcher on 2017’s Mick Ronson documentary Beside Bowie.