The best advice that Gavin Rossdale has ever received came when his band Bush were supporting David Bowie in the mid-90s. At the time, Bush were riding high. Their 1994 debut album Sixteen Stone, with its frenzied riffs and angsty, singalong choruses, had made the London quartet the latest grunge stars in a decade teeming with them, but there was a catch: bad reviews. Lots of bad reviews. It seemed that wherever Rossdale looked, someone was giving Bush an almighty kicking, each one making him want to throw himself out of the nearest window.

One night, he asked Bowie about it, enquiring: “How do you deal with this shit?” and the icon calmly imparted three words that became a mantra for the Bush frontman: “Outlive your critics.”

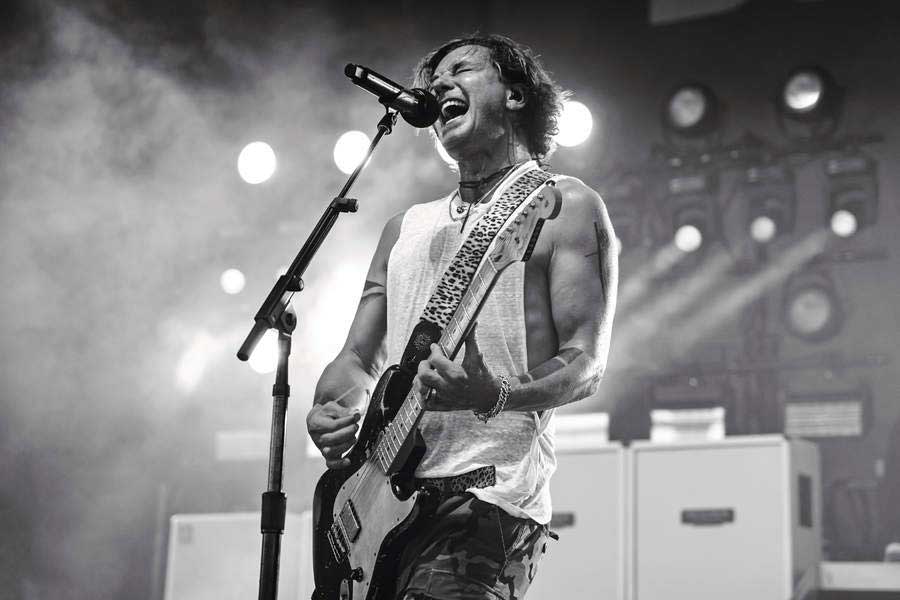

Rossdale tells that story with the breeziness of a man who’s just done that. His place as everyone’s favourite punch bag – albeit a punch bag with great hair and perfect cheekbones – has longsince been put to rest as, sitting in his hotel room in Oklahoma, he looks back over the group’s frantic early days. He lives in LA these days and has the tan to show it, although his accent remains true to his London roots.

“Even to recount it doesn’t make sense. It feels like a different age, a different time,” the affable 56-year-old reflects. “It had its moments, but if you didn’t sell any records and you had no attention, no one gave you a shitty review. I learned to live with it. It was a reaction to the success.”

For a moment, Rossdale is perplexed at how he let all the bad press get to him, and then he remembers. “We were all caught up in the romanticism of it that it really did matter. Anyone who’s in a band is a needy person that needs validation. Singers especially.”

These days, Rossdale is a lot more at ease with his place in the world. It’s 30 years since he formed Bush with original guitarist Nigel Pulsford, and he’s learned in the intervening period, which has taken in seven more Bush records either side of a group hiatus from 2002-2010, that being a musician is akin to being on a carousel.

“You keep doing what you do, and every now and again it comes back round into the light,” he says. “But you never know when the light is going to come back on you, so you try and keep good at every show and with every song.”

These tales of endurance funnel directly into Bush’s new ninth album, The Art Of Survival. Heavier than their early records, the riffs more barbed and the grooves more pummelling, its title is of huge importance to Rossdale.

“It’s massive for me,” he says. “It just came up to me and seemed the exact thing. All I see around me is survival, all I see every night when I play is individual acts of survival to get there. Going through the pandemic was a terrible great leveller for everyone. The Art Of Survival seemed very fitting.”

At the time we speak, Rossdale is on the road as part of a triple-header with Alice In Chains and Breaking Benjamin. Bush go on stage first, in the early-bird slot of 6.30pm. Pre-pandemic, it wouldn’t have been an option he would have considered, but the models for touring have changed.

“The reality was: do you want to struggle and play to six thousand people yourself while this other gig is going on over there, or be smart? There’s thirteen thousand people there when we play, so it’s really fun. We always have that slight underdog feel, but you know you’re going to go out and have a great show and play hard and fast for an hour.”

He especially enjoys it when he spots the other bands watching from the sidelines. “That’s when you know you’re cooking,” he declares. “If there’s no one at any of the shows, you’re like a sad entity, but when you’re creating a bit of a party and atmosphere, it’s fun, it’s a good vibe.”

Backstage, Rossdale is the sort of person who says hello to everyone – the other bands, the crew, the guys putting up the lighting rigs, the team sorting out all the pyrotechnics. Numerous jaunts around the US means that he knows lots of the local crew too; when he showed up in Houston recently, security asked about the whereabouts of his dog, Chewy.

“I like that,” he says, smiling.

Despite Bush’s longevity, Rossdale sees himself less as a veteran and more of what he describes as a “seasoned regular”. He feels like the group are in their second incarnation (which, considering he’s the only remaining original member, they are) because they don’t flood their live sets with a givethe-crowd-what-they-want run of 90s hits, instead dropping them in among the explosive licks and harder edges of their more recent material.

“I decided to delve into that heavier guitar world,” he says, “and it’s unleashed a new version of the band. I’ll play songs like that over songs that have been Number One because it’s not progressive, it’s not pushing. I see young people in the crowd thinking: ‘I don’t know this band, but fuck me!’. It’s been a new lease of life for us.”

He says that keeping things vital is key.

“I’m fucked now,” he says, “because I’ve given myself to rock music, and if no one really cares about it that much, then you’ve gotta keep finding ways to make yourself care about it and keep it interesting and keep it away from some homogenised sound that some rock can get. When you say the word ‘veteran’, the danger is that you make records in a perfunctory way, there’s a redundancy to it. I want every song to be bristling with energy.”

When he watches Alice In Chains, or listens to System Of A Down or Deftones, he admires how all their songs are pulling from the same sonic template, that there’s a thread running through it all. He says he couldn’t do that, though. “I’ve always been too unstable at trying to find different things to unlock the alchemy of music.”

You can trace that restless energy right back through his career, he says, offering Bush’s second album, Razorblade Suitcase, as an example. It’s a record that perfectly captures the push and pull at the heart of Bush’s success, entering the US Billboard chart at No.1 and going Top Five in the UK, while receiving several boots up the arse in the music press – it scored 2/5 in Rolling Stone and 1/10 in NME. More than that, though, Rossdale says it’s evidence of his bloody-mindedness.

“I went straight from having a huge record with Sixteen Stone to going to work with Steve Albini,” he says of the producer-engineer known for his no-frills, stripped-down approach to recording. “If I had been more commercially minded, and probably smarter, I would have continued with a more polished producer to continue in that zone. It’s a pretty funny record, because it’s just void of any editing. I listen to it now and I’m like: ‘Get rid of that bit, forfuck’s sake!’”

Rossdale revelled in that burst of mid-90s success.

“It was fantastic,” he recalls. “It just happened so fast, it had been so slow for so long.”

Before that, he says, he couldn’t get arrested. He knew all the A&R men around London, and would see them across the room at venues and think: “There’s the bloke who could change my life.” The problem was that they didn’t know who he was, his musical projects having failed to generate any sort of momentum.

“What’s funny is that anyone who doesn’t get signed for a long time and believes in themselves feels an endless shovel of disrespect being thrown in your face,” he says, laughing. “If you’re stupid enough, you just keep going.”

When Bush were finally offered a deal with Trauma, a small independent label based in the US, he reasoned that Pixies had to come to England to get a deal, with 4AD, so why couldn’t he do the opposite? “I thought, fuck it, let’s go there!”

For Rossdale it was a period that reinforced the idea of following your gut and believing in something, even if you don’t have any cause to.

“It allowed me to lean on my instincts,” he states. “It was magic to be accepted and to have an audience and to reach a lot of people. I’d been struggling for so long, and it felt like I was in the right suit, like: ‘Oh yeah, this is what I was meant to wear all along.’”

He thinks that part of the initial UK push-back to his band was down to the fact that Bush emerged around the same time as Britpop was becoming a mainstream cultural crossover.

“I was in a rock band with ‘grunge’ leanings, for lack of a better word, when Suede were the saviours of British music,” he says. “I appreciate those Britpop bands, but I just happened to like a certain type of performance, and you can’t perform the way I like to perform without a strong guitar backing and feedback and mayhem. A more ordered style never suited how I wanted to be on stage.”

There have been times in his career when Rossdale has contemplated the diversion he made into writing the hard rock anthems that became Bush’s stock-in-trade, and thought to himself: ‘Why did I do that?’ As a young songwriter, his favourite bands were The Psychedelic Furs, Public Image and The The, none of whom are especially known for distorted chaos.

It was when he saw Jane’s Addiction perform at the Acklam Hall in West London that everything changed.

“It was the energy on stage, these metal-esque riffs and this powerful music,” he marvels. “I loved My Bloody Valentine, but I’d go see them and wasn’t blown away by the performance aspect. When I saw Perry [Farrell, Jane’s frontman], he was such a showman.”

Soon after, a new wave of bands – Tad, Soundgarden, Alice In Chains and Nirvana among them – spoke to him as an artist in a way that none had previously. He could do it too, he thought to himself. “All I’d known of rock music before that was Guns N’ Roses and Sunset Strip and hair metal. I thought: ‘I can’t sing that high and I don’t look like that.’ But when I heard all those [new] bands, I was like: ‘Wow!’ That’s where my love affair with heavier stuff came in.”

The fact that, three decades on, he’s on the road with Alice In Chains isn’t lost on him. Through a mutual friend he’s become close pals with AIC guitarist Jerry Cantrell. “Being on tour with them, hearing Man In The Box and realising that in 1991 that was the first one where it was: ‘What is this?!’ Life is full of weird circles.”

As much as The Art Of Survival is about the pandemic and the power of people pulling through together, there’s also another, deeper and more personal theme running through Bush’s new record, one born of break-ups and divorce, of having your name dragged through the mud in tabloids and gossip columns and surviving that. In case you’ve been living under a rock, or your subscription to Hello! magazine has lapsed, Rossdale was married to No Doubt’s Gwen Stefani for 13 years until the couple went through an acrimonious split and divorce in 2015.

“There was one point a few years ago where I was like: ‘I’m married, three kids, I’m falling off a cliff here!’ And then you go through a crazy divorce and personal stuff that’s on the edge of an abyss. As an artist, it’s the most vitalising thing you can get. It’s like I got a shot of adrenaline over a few years. It allows me to have a lot of honesty. It’s a very honest record.”

Rossdale did ask himself whether he should talk about the split and present The Art Of Survival in the light of what he went through, and deemed it not the way to go about things.

“It would put too much of a print on something in terms of its genesis,” he offers, “and would alter people’s experience of it and put too much of me on it.”

The problem is that some questions lead right back to that door. As he ponders what the most hurtful thing anyone could say to him is, he returns to the subject.

“I went through a manic public divorce where one person gave their version, and I shut my mouth because we’ve got kids,” he says. “Life has moved on, but it was a really tough time. They say divorce and death are the two hardest things to go through, so I’m one down!”

Looking back on it all, he says he has learned to be more careful and not so blasé about consequences. “It’s a personal matter but it got out of hand. I’d been so reckless, so my personal journey was to stop being reckless and sort myself out. Which I did. I slowly came back to myself and wrote this record.”

He describes the new album as “strong and resilient and powerful and empathetic”. He also says there was a moment during the pandemic when he wondered if he would ever come back again, but has emerged re-energised. Perhaps that’s partly due to recognising where he’s at in life. He might look good for his age, but there’s no getting away from the fact that he’s only a few years off 60.

“I appreciate there’s a horizon,” he says. “The genius of youth is its ignorance. Like: ‘I’m always gonna be successful, I’m always gonna be winning awards, I’m always gonna get shit reviews but I’ll have massive crowds.’ But that’s not the case. It’s like you’re teetering on this precipice the whole time. I made this record on a precipice, fully aware that anyone can knock you off and, unless you’re really good, you have no place being there.”

If anything, the past few years have hardened Rossdale’s resolve not to let all this pass him by. He wants Bush’s music to stand out. It’s why he keeps tweaking their sound, chasing whatever it isthat made him start the band in the first place.

“I want to be one of the bands in rock music that makes interesting music,” he concludes, “where rock is seen as something exciting and modern. Creatively, in the rock world, we need as many brilliant records as possible. It’s not a competition. The competition is with yourself.”

Gavin Rossdale knows that a life in music is like being on a carousel. He’s patiently waiting to come around again into the light.

The Art Of Survival is out now via BMG.