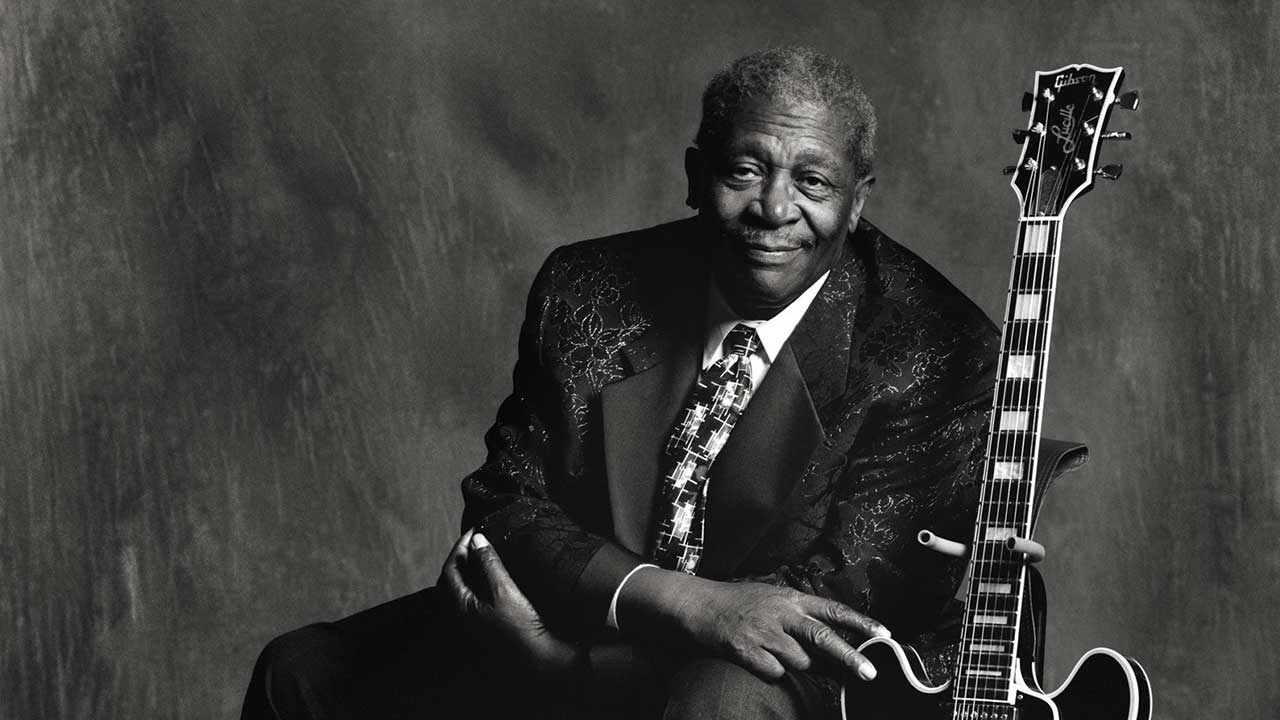

At the time of BB King's death in May 2015, the man born Riley B King in mid-20s Mississippi was the undisputed King Of The Blues. The ‘Blues Boy’ survived brutal racism, extreme poverty and even a brief association with U2 to endure as the ambassador for a style of music that has defied being written off countless times.

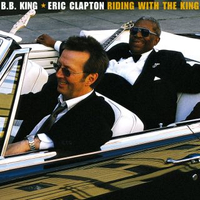

Stylistically, BB King’s first few albums were heavily indebted to his idol T-Bone Walker, but by the early 60s he was his own man, and a powerful influence on a gang of white kids in London that included Peter Green, future Rolling Stone Mick Taylor and those two’s predecessor in John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers, Eric Clapton.

“If you’re not familiar with his work,” said Clapton, “I would encourage you to go out and find an album called Live At The Regal, which is where it all really started for me as a young player.”

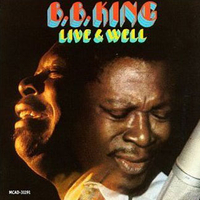

Released in 1965, Live At The Regal, the first of BB King’s masterpieces, finds an artist in complete control of his audience. While many blues performers were backtracking on their careers to satisfy a new white Delta blues-obsessed audience, King gave his predominantly black followers exactly what he wanted: progression. His music took on elements of jazz, funk and soul while never obscuring his first love, the blues.

When he did cross over to a young white rock audience at San Francisco’s Fillmore Auditorium on June 6, 1968, it was on his own terms. At a time when his contemporaries Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf were talked into cutting career-low psychedelic shit to pander to the hippies [Electric Mud in ’68 and The Howlin’ Wolf Album in ’69 respectively], BB King went in the opposite direction. With The Thrill Is Gone, from his ’69 album Completely Well, he recorded a new, sophisticated blues, augmented with orchestral strings.

Even in his dotage, BB King maintained a punishing touring schedule. No one, to paraphrase one of his classics, paid a higher cost to be the boss, and despite his wealth, he feared slowing down: “If we don’t work, how we gonna eat?”

That work ethic, forged in the poverty he experienced as a child, is there in his discography too. When he released Completely Well in 1969, he was already on his 17th studio record.