The John Mayall albums you should definitely own

The Godfather of British blues introduced Eric Clapton, Peter Green, Jack Bruce and Mick Taylor to the world, and has made 60 albums in nearly 60 years

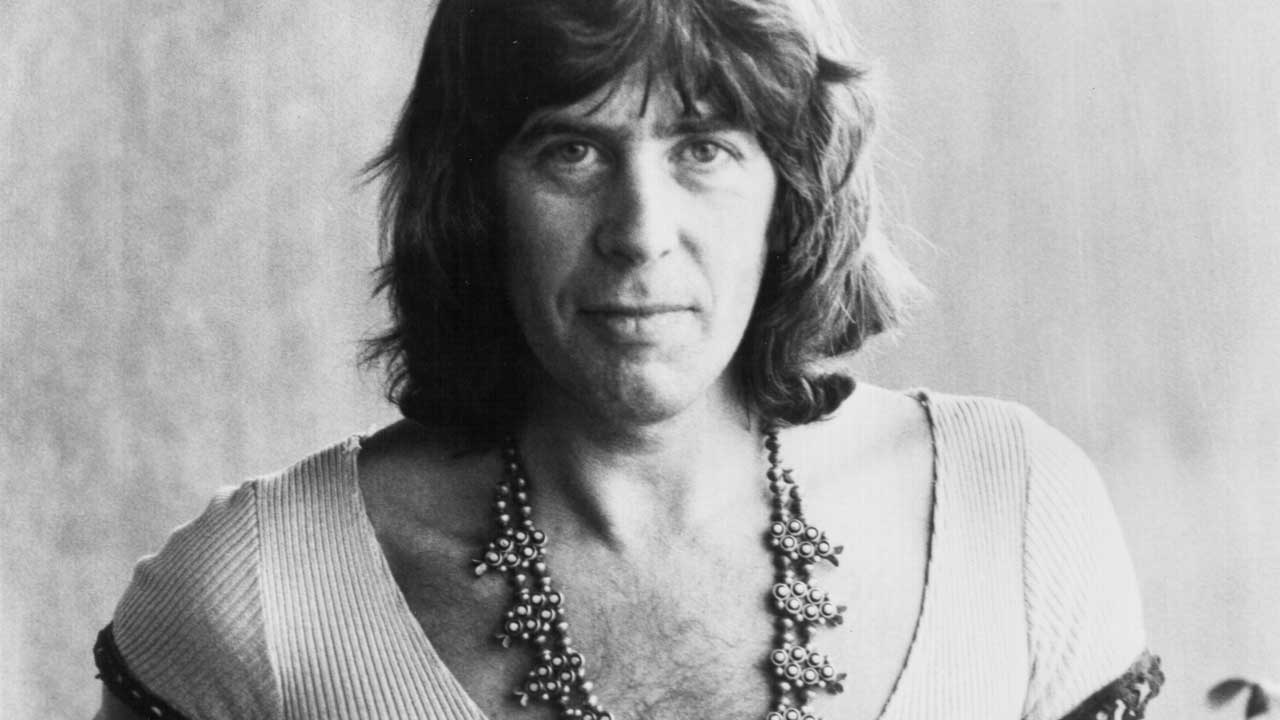

Plenty of British bluesmen have sold more records, but few command as much respect as John Mayall OBE. With a back catalogue of close to 60 albums, and kick-starting the careers of countless stadium-filling galacticos, there’s a solid pub argument that nobody has done so much, for so long, to keep British blues afloat. No wonder they call him the Godfather.

Mayall almost missed the boat. Born near Macclesfield in 1933, he grew up in thrall to his father’s imported collection of blues 78s, and taught himself piano, guitar, harmonica and ukulele during downtime at art school. But National Service knocked him off track, and he returned to 1950s Britain to find a monopoly of trad-jazz bands “all playing the same tunes”.

At last, in 1962, he sensed revolution in the air, and the following year he hit London like a train. Even back then, pushing 30, the bandleader seemed like an elder statesman; a silverback among the cubs of the nascent British scene, whose gravitas, brittle wit and deep knowledge of the genre’s roots made him a big fish at Alexis Korner’s Ealing Club.

“London was booming,” Mayall recalls. “I was just glad the music I’d played since I was a kid was now a viable thing.”

With impeccable timing, Mayall launched The Bluesbreakers, and so began an imperious early run of albums that remain set-texts for anyone remotely serious about the blues. This was Mayall’s band (the turnover of hired/fired members backs up his former guitarist Walter Trout’s observation that he was a “benevolent dictator”). But alongside the prolific songwriting, stinging musicianship and tremulous vocals, his genius lay in the nabbing and nurturing of ‘next big things’. In the 60s especially, the talent on the payroll was staggering – Eric Clapton, Peter Green, Jack Bruce, Mick Taylor. And Mayall always let his charges off the leash. “Any person who joins my band,” he noted, “they’re all equal, whatever their age.”

Mayall, now 90, retired from the road in 2021, but continues to make music that pleases the hardcore but make little dent in the mainstream (his last album, 2022's The Sun Is Shining Down, was his 60th). And while it’s unlikely he’ll produce anything to shuffle the pecking-order laid out here, you can bet he’ll go down trying.

“With music you can be any age,” he noted in 2012. “There’s no end in sight yet.”

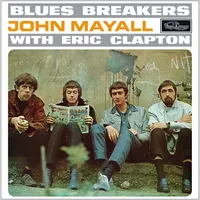

John Mayall And The Bluesbreakers - Blues Breakers With Eric Clapton (Decca, 1966)

The inevitable first purchase, 1966’s so-called Beano album is the high-water mark of the 60s British blues boom, Mayall’s finest hour and Eric Clapton’s precocious launch pad.

From the languid opening swoop of Otis Rush’s All Your Love, through the jet-fuelled Hideaway, to spring-heeled Mayall originals like Key To Love and Little Girl, this is amped-up blues rock that walks a tightrope between reverential and rip-it-up exciting. Nearly 50 years after it hit number six in the UK, there’s a case for saying that nobody involved has ever flown higher.

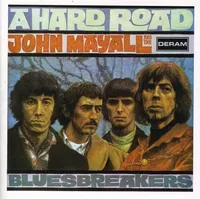

John Mayall And The Bluesbreakers - A Hard Road (Decca, 1967)

Producer Mike Vernon hit the roof when The Bluesbreakers rolled into Decca Studios without Eric Clapton. He needn’t have panicked. The canny Mayall’s new signing, 20-year-old nonentity Peter Green, was patently up to snuff, whether bleeding soul over his self-penned instrumental The Supernatural, detonating Freddie King’s The Stumble, or dovetailing with Mayall on top-drawer originals like the morose title track.

Green and bassist John McVie would split that same year for Fleetwood Mac, but their legacy is an album that snaps at The Bluesbreakers’ heels.

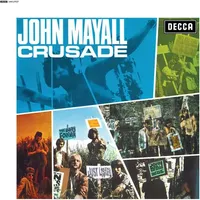

John Mayall And The Bluesbreakers - Crusade (Decca, 1967)

Mayall was outraged by the untrumpeted death of J.B. Lenoir, and Crusade was his attempt to force the blues down the throat of the mainstream (“I hope you’ll join forces with me,” he writes in the sleeve notes).

With Green gone, his eye had settled on a teenage Mick Taylor, who brings equal parts soul and swagger. Crusade took just seven hours to record and mix, which perhaps accounts for its wham-bam brilliance. The band tips its hat on The Death Of J.B. Lenoir, and Taylor arguably pips Clapton’s Hideaway with his jaw-dropping instrumental Snowy Wood.

John Mayall - Blues From Laurel Canyon (Decca, 1968)

Mayall had spent the summer of 1968 crashing at Frank Zappa’s dissolute Laurel Canyon home. This loose concept album is his postcard, opening with the roar of an airliner touching down (Vacation), then lurching through sticky accounts of musos (The Bear) and LA groupies (the jazzy Miss James).

The rhythm section of drummer Colin Allen and bassist Steve Thompson provide a taut backbone, but the star of the piece is a ridiculously precocious Mick Taylor, whose pugnacious, heart-in-fingers fretwork made his exit for the Stones the following year feel like a step down.

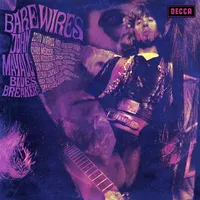

John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers - Bare Wires (Decca, 1968)

Bold moves all round, as Bare Wires binned the Crusade rhythm section, added brass and kicked off with a 23-minute title ‘suite’. Jazzier and lyrically introspective, the album rewarded open-minded listeners with a volley of cuts that still dazzle, from the rug-cutting funk of No Reply (Mick Taylor working the wah-wah pedal with Hendrix-worthy panache) to the parping slow-blues of I’m A Stranger.

It tested the faith of his trad-blues fans, but the consensus was a thumbs-up: Bare Wires gave Mayall his highest UK chart placing (number three) and broke him in the States.

John Mayall - The Turning Point (Polydor, 1969)

By the end of the 60s, the man who mobilised electric blues was restless, dropping the Bluesbreakers brand and recording a live album of self-described “low-volume music”. Out went the drums and blazing lead guitar; in came John Almond’s saxophone and Jon Mark’s acoustic finger-style nuances, for some of the folkiest and rootsiest tracks of Mayall’s career.

So Hard To Share drips atmosphere, and I’m Gonna Fight For You J.B. is campfire- intimate, but the pick is the closing Room To Move, its chippy harp-led strut remaining a high point of Mayall shows to this day.

John Mayall - USA Union (Polydor, 1970)

Mayall’s recruitment of an all-American band was a blow to national pride, but the line-up of Canned Heat’s Harvey Mandel and Larry Taylor alongside the emotive electric violin of Don ‘Sugarcane’ Harris proved a potent mix on this love-letter to then-partner Nancy Throckmorton.

With its generally laidback vibe, it’s the spiritual sequel to The Turning Point, and while the material isn’t quite up to that album there is frequent magic in highlights like You Must Be Crazy and Crying. Best of all is Nature’s Disappearing, its jazzy lilt concealing a stinging ecological polemic (‘Man’s a filthy creature, raping the land and water and the air…’).

John Mayall - Back To The Roots (Polydor, 1971)

It was certainly a star-studded prospect, with Bluesbreakers alumni Clapton, Taylor and Keef Hartley briefly lured back to the fold, alongside Mayall’s US band of the period. In practice, while the chemistry doesn’t always spark like the old days, Back To The Roots offers enough gems for a spot on the podium.

Prisons On The Road is a barrelhouse pop at the daily commute, and Taylor has rarely sounded sweeter than on Marriage Madness, but the peak is Accidental Suicide, on which the guesting guitar heroes jockey for position. Remixed versions appeared on Archive To The Eighties, but Roots is the better option.

John Mayall - Jazz Blues Fusion (Polydor, 1972)

Don’t let the cappucino-and-polo-neck connotations of the title scare you off. Mayall lured a crack squad of jazz cats into the fold – including guitarist Freddy Robinson and trumpeter Blue Mitchell – but this live album is anything but po-faced muso pseudery.

Between the upbeat anarchy of Good Time Boogie and the brassy bounce of Mess Around, there’s plenty to scratch the hard-core’s blues itch, while there are few finer showcases for the bandleader’s formidable harp chops than Exercise In C Major. Mayall deemed the short-lived line-up a “dynamite combination”, and this album sounds like one hell of a night out.

...and one to avoid

You can trust Louder

John Mayall - Big Man Blues (Music Avenue, 2012)

John Mayall doesn’t make ‘bad’ albums as such, but he does knock out the odd workmanlike one. There’s nothing wrong with this one, recorded in the early 80s and repackaged various times since. The line-up – James Quill Smith, in particular, is a capable guitarist – make a decent fist of cuts like Jimmy Reed’s Baby, What You Want Me To Do and J.B. Lenoir’s Mama Talk To Your Daughter.

Elsewhere though, on some lacklustre Mayall originals like John Lee Boogie, there’s a wagon-circling feel, and changes that can be seen coming a mile off. Not a car crash, it’s just another so-so blues album. And God knows we’ve got enough of those.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Henry Yates has been a freelance journalist since 2002 and written about music for titles including The Guardian, The Telegraph, NME, Classic Rock, Guitarist, Total Guitar and Metal Hammer. He is the author of Walter Trout's official biography, Rescued From Reality, a music pundit on Times Radio and BBC TV, and an interviewer who has spoken to Brian May, Jimmy Page, Ozzy Osbourne, Ronnie Wood, Dave Grohl, Marilyn Manson, Kiefer Sutherland and many more.