The Roy Harper albums you should definitely own

Led Zeppelin wrote a song about him, Pink Floyd invited him to sing on another, but this is the very best of Roy Harper's own recorded work

Folk stylist, protest singer, poet, rocker, rebel prophet… There hasn’t been anyone else quite like Roy Harper. His sheer plurality, lashed to a bloody-minded refusal to tailor his music for the commercial market, has made him special, and also consigned him to a career of eternal cultdom. He’s an artist capable of writing the most delicate acoustic song one minute, a raging, emotive social critique the next. He’s a mercurial figure who, by his own admission, “divides opinion a lot”.

Harper has always had friends in high places. The journey from “impressionable little beatnik” of the 60s to the folk-rock titan of today has produced 21 studio albums and plus live recordings, peppered with appearances from the likes of David Gilmour, Kate Bush, John Paul Jones and, most prominently, his great friend Jimmy Page. Led Zeppelin included the tribute Hats Off To (Roy) Harper on their third album, while Pink Floyd brought him in to sing Have A Cigar on 1975’s Wish You Were Here.

Harper was born in Manchester in 1941. He survived a tortuous early life of homelessness, petty crime and prison, fetching up on the Soho folk scene of the early 60s. He was never a folkie in the traditional sense, though, and laced his songs with a freewheeling sense of experimentation. His spate of scintillating albums in the 70s – from Flat Baroque And Berserk through to Bullinamingvase – have been hugely influential.

In the 80s Harper found himself stigmatised as part of the old guard that punk and new wave had supposedly swept away. He nonetheless recorded some fine records, among them 1985’s collaboration with Jimmy Page, Whatever Happened to Jugula. The following decade found him in exile in Ireland, where he still lives, quietly releasing albums of extraordinary power, chiefly Death Or Glory? and The Dream Society.

His last studio release was 2013’s critically acclaimed Man and Myth, which featured a guest appearance from The Who's Pete Townshend on Cloud Cuckooland. Now in his 80s he remains an uncompromising talent, admired by everyone from Robert Plant and Ian Anderson to Johnny Marr and Joanna Newsom. His influence on the folk and rock fraternity is immense.

“Of the creative peaks I’ve had it’s definitely one of the mountains,” Harper says of this undisputed masterpiece. Complex, elliptical and fabulously expressive, Stormcock consists of four pieces that form a cogent song-suite.

He takes a broadsword to the judiciary system and rock critics alike on Hors D’Oeuvres, while the glorious The Same Old Rock – featuring a star turn from Jimmy Page under the guise of S. Flavius Mercurius – swings a paw at religious dogma. Pick of the bunch might just be the spirited eco anthem Me And My Woman. Stormcock was way too out-there for EMI, who greeted its lack of potential hit singles by not promoting it at all.

Harper’s mostly overtly rockist album is given real punch by a backing band comprising guitarist Chris Spedding, Dave Cochran (bass) and drummer Bill Bruford.

The two standout tracks are epic in every sense. David Gilmour and John Paul Jones are on hand for The Game, an eloquent discourse on what it is to be human; When An Old Cricketer Leaves The Crease is a near-perfect hymn to mortality and Englishness, given added poignancy by David Bedford’s arrangement and the brass of the Grimethorpe Colliery Band. In a more forgiving world this would have been the record to finally tip Harper into the mainstream.

Flat Baroque And Berserk (Harvest, 1970)

The move from Liberty Records to EMI’s ‘underground’ imprint Harvest ushered in an era of intense creativity for Harper. This fourth album marked his first entry into the British album chart and remains his top seller.

Its centrepiece is the remarkable I Hate The White Man, a pungent slice of Harper polemic that attempts to assert everybody’s right to freedom and equality. The other standout is the pastoral Another Day. In a typically perverse move, closing tune Hells Angels is a raucous, ragged send-off co-starring Keith Emerson’s The Nice and designed to make you leap for the off switch.

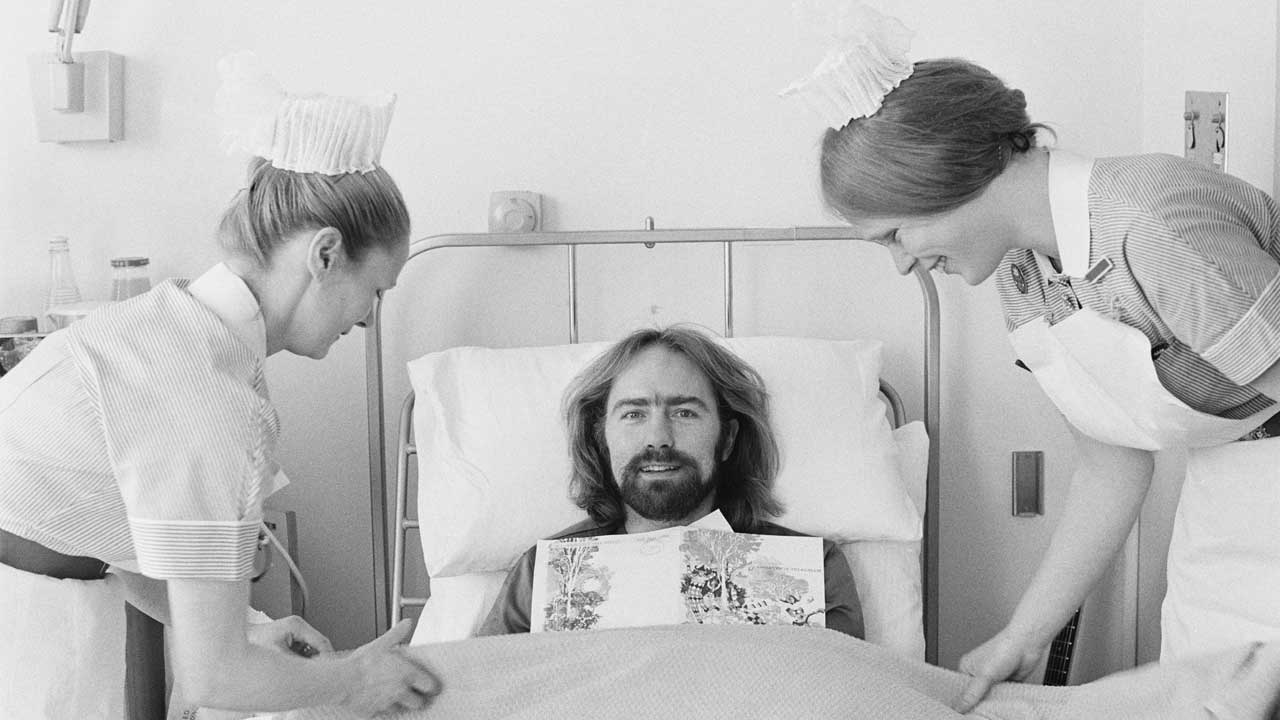

Written after a congenital blood disorder had seriously threatened Harper’s life, this record was dominated by The Lord’s Prayer, a side-long treatise on the follies of man and the struggle between spirituality and technology. It was, in his own words, “my last will and testament”, with a little help from Jimmy Page on guitar.

Other notable tracks include South Africa, which equated a nation in the grip of apartheid to a prospective lover waiting to be freed, the terrific Highway Blues, and All Ireland, a plea for political and tribal tolerance. Some of the album’s songs were written for Made, the 1972 film that cast Harper alongside Carol White.

Bullinamingvase (Harvest, 1977)

Harper’s last hurrah of the 70s is bookended by two glorious versions of One Of Those Days In England. The first is the wistful, almost carefree single version; the second a darker, labyrinthine study of the cultural sweep of his homeland.

Alongside the gorgeous Cherishing The Lonesome sits Watford Gap, an ode to the famous road-stop on the M1 motorway as hilarious as it is scathing. The singalong chorus – ‘The Watford Gap, the Watford Gap/A plate of grease and a load of crap’ – landed Harper in serious bother with the owner, who just happened to be a prominent board member on EMI, Harper’s label.

Death Or Glory? (Awareness, 1992)

Perhaps Harper’s most emotionally racked album, written after the failure of his second marriage. “There was nowhere for me to hide,” he said later. The title track, One More Tomorrow and Waiting For Godot Part Zed are full of melancholy and despair, yet remain oddly luminous.

It wasn’t all self-absorption, though. Harper also tackled the Gulf conflict and its attendant media frenzy, the need for a global consciousness, and offered a eulogy to murdered Amazonian activist Chico Mendes. On the lighter side, there’s a warm tribute to hero Miles Davis, and a song written for Robert Plant’s daughter’s wedding.

Flashes From The Archives Of Oblivion (Harvest, 1974)

This storming live double album, essentially an early ‘best of’, gives some indication as to the rambunctious nature of an early-70s Roy Harper show. There are inflamed takes on Me And My Woman, South Africa and One Man Rock And Roll Band, while a driven Highway Blues borders on the manic.

It’s notable for Kangaroo Blues and Home, and being partly recorded at Harper’s infamous Valentine’s Day bash at London’s Rainbow with Jimmy Page, John Bonham, Keith Moon and Ronnie Lane. The sleeve caused a rumpus too, with women workers at EMI’s factory refusing to handle it.

The Green Man (Science Friction, 2000)

This back-to-roots affair finds Harper in acoustic mode, with extra shading from the Tea Party multi-instrumentalist Jeff Martin. The onset of Harper’s 60th year did little to dilute his bile, with The Monster in particular a withering attack on Tony Blair and New Labour.

Elsewhere, Rushing Camelot is an erudite hymn to Mother Earth in the face of scientific progress, All In All tips the wink to Aldous Huxley’s novel The Doors Of Perception, while the pagan-leaning title track manages to sound both ancient and modern. He wasn’t done with Blair either. Harper’s 2005 single The Death Of God is an impassioned, 15-minute rant against the invasion of Iraq.

Counter Culture (Science Friction, 2005)

Perhaps the best portal of entry for beginners, this is a double compilation covering 35 years of uncommon songcraft, cherry-picked by Harper himself. Much of what makes him special is here, including two songs with Jimmy Page on guitar (The Same Old Rock and Frozen Moment), and the very lovely You which features David Gilmour and long-time fan Kate Bush.

Blackpool, meanwhile, is the tune that first alerted the young Page to Harper’s talents back in the 60s. I Hate The White Man and When An Old Cricketer Leaves The Crease are among the choice moments, as is proto-hippie anthem You Don’t Need Money.

And one to avoid...

You can trust Louder

Harper admits that the early 80s were “the nadir of my life in music”. Cast aside by EMI and suddenly “completely out of fashion” in the post-punk age, he co-founded his own label to release Work Of Heart. The songs suffer from lack of focus or snap, while the whole shebang (with full backing band) sounds over-produced. Harper later released the superior demos of the album, which were infused with a rawness lacking in the finished product, as Born In Captivity.

Also to be avoided is the EP Burn The World. Written in 1983-4 but not released until 1990, it’s two versions of the 20-minute song of the same name, one live, one in the studio.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Freelance writer for Classic Rock since 2008, and sister title Prog since its inception in 2009. Regular contributor to Uncut magazine for over 20 years. Other clients include Word magazine, Record Collector, The Guardian, Sunday Times, The Telegraph and When Saturday Comes. Alongside Marc Riley, co-presenter of long-running A-Z Of David Bowie podcast. Also appears twice a week on Riley’s BBC6 radio show, rifling through old copies of the NME and Melody Maker in the Parallel Universe slot. Designed Aston Villa’s kit during a previous life as a sportswear designer. Geezer Butler told him he loved the all-black away strip.