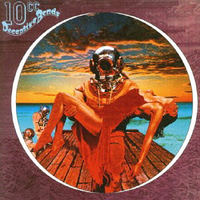

The Manchester four-piece are one of the most brilliant – radical, even – rock groups this country has ever produced. Who says so? John Lydon, for one, hailed 10cc’s genius. And Trevor Horn for another; the super-producer might not have been able to effect his sonic changes without the giant leaps that 10cc made at their Strawberry Studios in Stockport between 1973 and 1976, when they did their best work.

It’s strange to consider that this most 70s of bands, steeped in state-of-the-art technology, postmodern peers of David Bowie and Roxy Music, as smart as Sparks and Steely Dan, had a pre-history in the 60s.

Graham Gouldman was a songwriter for The Yardbirds (For Your Love, Heart Full Of Soul), The Hollies (Bus Stop) and Herman’s Hermits (No Milk Today). Eric Stewart had been a 60s heartthrob as lead singer of The Mindbenders. By 1970 Stewart had joined forces with art-school brats Lol Creme and Kevin Godley to form Hotlegs, who had a UK No.2 (and worldwide) hit with Neanderthal Man. With Gouldman back in Britain, the four enjoyed a brief tenure as Neil Sedaka’s backing band in the early 70s, when they realised it was time to record music of their own.

The results were unique, the next logical step after Abbey Road, only instead of a Lennon & McCartney-style dominant partnership, all of 10cc could sing, play various instruments and produce (with Stewart their own George Martin). They also wrote in several permutations: Gouldman and Stewart were purveyors of perfectly crafted pop-rock and beautiful anti-ballads; you may be familiar with I’m Not In Love.

Meanwhile, Godley and Creme’s songs were zanier. But Creme-Stewart compositions such as Life Is A Minestrone had a comic daring all their own, Creme-Gouldman wrote the ingenious The Worst Band In The World, and Stewart-Godley offered deft rocker Oh Effendi. Or they might all join forces and create a Zep-heavy monster like The Second Sitting For The Last Supper.

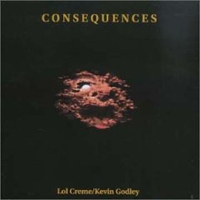

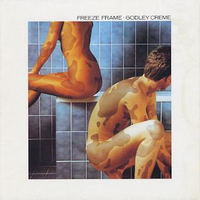

Truly, anything was possible. Theirs was music of vaulting ambition, cinematic in scope, literate, endlessly witty and intelligent. And then they went their separate ways – Gouldman and Stewart to continue as 10cc, Godley and Creme to pursue numerous projects. Which left twice as much product to buy. But which ones do you really need? Read on…