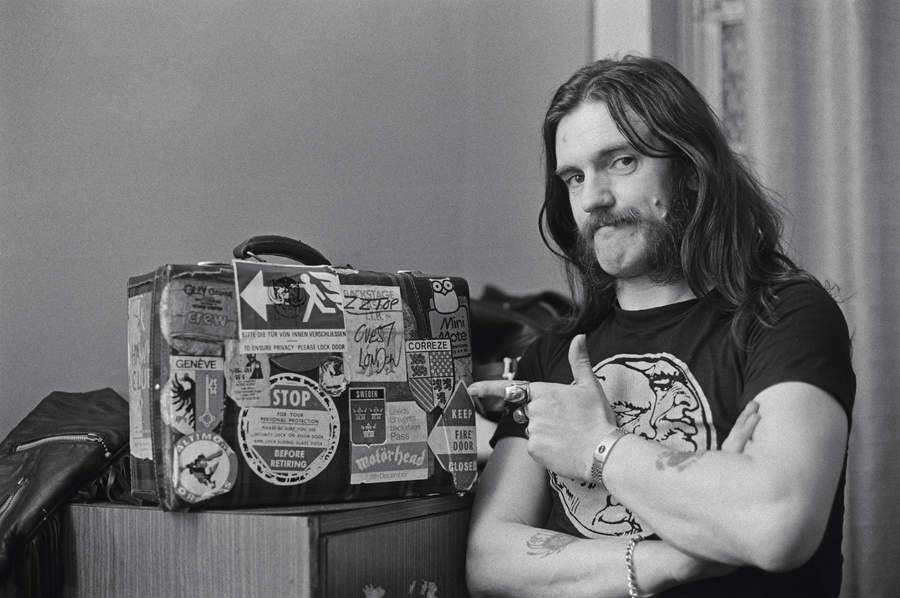

For the rest of his life, Lemmy would look back on the aftermath of Motörhead’s crowning glory with their 1981 album No Sleep ’Til Hammersmith and protest thatit wasn’t his fault they could never follow it up.

“The trouble is, you can’t follow a live album that went straight in at Number One,” he said. “I mean, what do you do? You can’t put out another live album. And you can’t follow it with a studio album because that’s been the live album people have been waiting for for five years, right? So we were fucked whatever we did. We could have done the best studio album in the world and we would have been fucked. Except we didn’t, we did Iron Fist.”

In reality, no one wanted or expected another live album. What Motörhead’s fans did expect was a new album as good as the previous three, the unholy trinity of Overkill, Bomber and Ace Of Spades. What no one saw coming was Iron Fist, 12 tracks light on inspiration and spirit, overloaded with arrogance and disaffection. Exactly the kind of ill-starred, done-quick, out-of-control album that events leading up to its creation all but guaranteed.

As guitarist ‘Fast’ Eddie Clarke told me: “Iron Fist was the toughest because we were getting low on ideas and things were getting strained.”

Drummer Phil ‘Philthy Animal’ Taylor was particularly affected by the onrush of fame, Eddie claimed.

“Lemmy was not himself, either… Indeed, Lemmy had begun to delight his ego just a tad too much of late. Playing the biggest show of their career so far, headlining a six-band line-up billed as the Heavy Metal Barndance at Bingley Hall in Stafford, in 1981, Lemmy collapsed halfway through; the rest of the show was cancelled.

“Lemmy’s been up for three days drinking vodka,” said a still pissed-off Clarke. “He’s been fucking chicks all day and we’ve got twelve thousand kids crammed waiting for us. All day people have been offering me lines of coke, and I’ve only had one fucking Heineken because I want to be together for this show.

“Fifty-five minutes into the set, Lemmy disappears backwards, collapses on the stage. Me and Phil are furious. ‘You let us down, you c**t!’ And he’s saying: ‘Me being up for three nights has nothing to do with it.’ Of course not!”

The irony was that the show received an ecstatic review in Melody Maker, whose reviewer thought it the most marvellous theatre.

“I said to Phil: ‘Suddenly we’re the definitive live band. They were calling us c**ts last week,’” Lemmy said, chewing a cigarette.

As Mick Farren, who’d known Lemmy since Hawkwind days, co-writing songs with him, observed: “We were all exceedingly badly behaved. We all took far too many drugs. Lemmy took more speed than any human being I’ve ever seen. We probably deserved to go to jail many times over.”

In fact, they very nearly did when the band suffered a series of busts in the run-up to the release of Iron Fist in April 1982. The first and most serious, after a four-night run at London’s Hammersmith Odeon, was when all three had their homes raided by the drugs squad.

“Turned out the cops had been at the gig every night of the Hammersmith run,” their former manager Doug Smith recalls. “They even bought T-shirts from the stall, to look like punters. Then at six the morning, after the final show, twenty-six officers rammed open my front door – took it off the hinges. Another seventy of them went to the hotel where the crew were.

"They did Lemmy’s flat, too, but Lemmy wasn’t there. As usual he got away with it because he was out snorting and drinking in the St Moritz club in Soho, on the fruit machine. Next morning he goes: ‘Oh, I didn’t know this all happened, Doug.’”

Away from the stage there were also growing disputes over money. As far as the band were concerned, they’d just had a No.1 album with No Sleep and should be rich. Yet they were all still on a weekly wage of £250. Despite sold-out concert halls in Britain and Europe, Smith points out that “the majority of the tours didn’t make a lot of money. The merchandising made a lot of money. When the band really got into problems, the merchandising company lent them £36,000, which they never saw again.

"Eddie would moan: ‘Where did all the merchandising money go, Doug?’ Eddie, you had it. ‘Well, we never saw any of it.’ No, you never saw any of it. We just paid your fucking bills!” Doug had “protected” Motörhead: “They always had money to go on the road.”

Which was all Lemmy cared about. “Lemmy wasn’t really interested in money. Just what was in his pocket. As long as he had an unlimited amount to spend on machines or whatever…” The ‘whatever’ being speed and whisky, obvs.

Eddie, though, was having none of it, and on more than one occasion threatened to leave the band, an almost weekly occurrence, according to Lemmy. He recalled Eddie ‘leaving’ once on tour in France. Panicked label chiefs flew over in a charter plane and eventually Eddie was talked out of it.

“Much against his better nature and all that shit,” Lemmy frowned. “The only thing they didn’t do was promise him more money. If he’d had any sense he would have held out for that.”

Doug Smith tells of an occasion in LA when Eddie phoned, ranting and raving. “The fucking band left the gig without me! I had no fucking car to get back to the hotel! I had to get a fucking taxi and the driver tried to kidnap me and take me to Mexico! I’m leaving the band!”

Doug took a breath, then “very calmly said: ‘Eddie, I understand all that, but my wife has just gone into labour.’ He went: ‘Oh, sorry. I’ll leave the band next week, then…’”

This was the disaster zone backdrop to what would become the benighted Iron Fist, the last album the classic Three Amigos lineup of Motörhead would ever make – and easily the worst.

“Eddie and Phil were always having fistfights,” Lemmy told me. “At one point, I’ve separated them cos it’s time to go onstage and on the way down the stairs Phil’s hit Eddie round the head with a fucking drumstick and it’s started again. In Glasgow they rolled on the floor into the elevator. The doors shut and they’re still fighting.”

He lit another cigarette. “Bands are very fragile things. If they’re not getting enough money there’s not much to hold them together except trust, and very few bands trust each other after about the first year. They’re all in it for themselves. And that’s what I tried to fight in Motörhead. I wanted it to be a band that believed in what we do and believed that we’re valid. Every great band goes through that shit. We just did it for longer.”

They had been together for nearly seven years when they arrived in the studio to make Iron Fist. “We were sick to death of each other by then,” Phil told me. “But it wasn’t exactly new. Lemmy had always been an arsehole. Eddie was always a fucking pain.”

Lemmy later claimed that it was during this spell that Eddie “stole one of my birds”. When I reminded him, Eddie shook his head and laughed. According to Smith, “Lemmy didn’t really have relationships. Girls were just something Lemmy shagged. There was very little love there.”

When Eddie took up an offer to produce an album for a new powerhouse trio called Tank, that had supported Motörhead on tour, Lemmy began calling Eddie ‘Fancy Bollocks’. It was a situation that became even more tense when Taylor suggested Fancy Bollocks also produce the next Motörhead album.

Originally the plan had been to work with Vic Maile, the man with the golden touch who had produced No Sleep, Ace Of Spades and Bomber. But Taylor and Maile had a big row over a new drum kit, culminating in Taylor issuing the ultimate rock-star ultimatum:

“Either he goes, or I do.” The star got his way and Maile was fired.

Taylor again suggested Clarke step in. He’d one a great job on the Tank album, Filth Hounds Of Hades, which had just come out to rave reviews. Lemmy wasn’t having it. Other noted producers were approached, but they all wanted top dollar from a band whose last album had gone to No.1. (But were still on £250 a week.) Lemmy finally caved: “Let Fancy Bollocks produce it, then.”

Time was hurriedly booked at Morgan Studios in West London. But Lemmy seemed to be phoning it in. Eddie: “I remember one particular incident. He’d done a wrong note. I said: ‘Look, Lem, can we straighten that note out?’ He said: ‘Oh, man, I ain’t got time. I gotta go.’ Cos there was some bird sitting there with her legs in the air and he wanted to go to the Speakeasy.”

Clarke was left with no option but to try to cut in a bass note that he played himself, using strips of razored tape in those pre-computerised analogue days. “That’s how much he didn’t want to be there.’”

Smith recalls Lemmy writing the lyrics to the title track while sitting in the catering room at the studio. “There was a girl there that served behind the counter, never met her before, and he would refer to her. He would write these lyrics, then go: ‘What do you think?’ She’d just sort of smile and go: ‘Yeah, very good.’ Another time he sat on the loo and wrote some lyrics as he was having a shit.”

Speaking 20 years later to Classic Rock’s Dave Ling, Lemmy admitted: “The Iron Fist album was bad, inferior to anything else we’ve ever done. There are at least three songs on there that were completely unfinished. But there you go. We were arrogant. When you’re successful, that’s what you become. You think it’ll go on forever.”

When Iron Fist was released in April 1982 it jumped into the UK chart at No.6 – then a week later began sliding sharply down again. Even the single – the title track and the only half-decent thing on the album – struggled to get into the Top 30 (peaking at No.29), whereas their previous single, a live in-your-face Motorhead from No Sleep, had reached No.6.

The fact is, Iron Fist was a DOA dud. Creatively, the band were running on fumes. The title track, built on the same non-shape-shifting machine-gun bass grumble as Ace Of Spades, Overkill and so many other earlier classics, makes it on familiarity alone. But it doesn’t matter if you ever hear it again.

The other 10 tracks… nothing further to say, Your Honour. Tracks like I’m The Doctor – excruciating dad-dancing punk – and (Don’t Let ’Em) Grind You Down – its payoff line was “Why don’tyou tell them to shove it!” Hardly in the same saloon bar as “I don’t want to live forever!” – were so shallow-end they barely got your feet wet. At least three are again built squarely on the same identikit badass bass riff; most noteworthy, Speedfreak (done countless times better and before in White Line Fever, Motörhead et al), but only because the others are so dire.

Panned by the same critics who’d been singing their praises for the past two years, the Iron Fist tour was nevertheless another sell-out – 24 shows including three nights at Newcastle’s City Hall, three nights in Birmingham and the four Hammersmith Odeon shows.

But the feeling backstage was no longer one of outlandish fun and overindulgence. I joined the tour for the Newcastle and London shows and the overindulgence was still much in evidence, but the fun, the filthy banter, the brotherly bullshit was notably thin on the ground.

“Lemmy was such a great frontman,” sighed Clarke. “One of my fondest memories is of Lemmy sweating his fucking bollocks off in that black silk shirt he used to wear. I get memories of that and it makes me choke. I fill up, cos we were at the height of our fame, and we were tanking.”

Lemmy was now a regular face in gossip columns, familiar in the same way as a Phil Lynott or a Ronnie Wood. When he turned up unexpectedly on Top Of The Pops with his new best friends the Nolan Sisters, as guest stars on the Young & Moody Band single Don’t Do That, everyone grinned knowingly at Lemmy in his white waiter’s jacket and mirrored sunglasses. Lemmy looking both dangerous and… cute.

The tabloid press had a field day. The Sun ran pictures of Lemmy cuddling 16-year-old Coleen Nolan. Word spread that Lemmy was doing his best to corrupt the youngest, prettiest Nolan – something she was happy to confirm years later: “When I was younger, Lemmy from Motörhead had a thing for my breasts. I turned him down, mainly because I knew I wouldn’t be able to take him home to my mother! He was lovely though.”

Phil Taylor affected not to give a shit about such shenanigans, while secretly wondering why he hadn’t been invited to the party. Clarke, though, quietly seethed. When Lemmy announced plans for Motörhead to collude with Plasmatics singer Wendy O Williams in a roughed-up version of the old Tammy Wynette chestnut Stand By Your Man, Clarke lost it.

The way Lemmy saw it, the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre EP the band had done the year before with Girlschool – under the nom-de-plume Headgirl – had given Motörhead their biggest-selling hit. Maybe this would work out that way too.

Clarke was appalled. “I thought it was absolute shit! The idea had come up after Lemmy had been pictured in the music papers with Wendy at the Marquee. Everybody went: ‘Wow, yes!’ Except me.”

Downer. Typical Clarke. Always moaning. He’ll stop in a minute. Only he didn’t.

The argument was still going on after they’d flown to Toronto for the start of their North American tour in May 1982. Lemmy saw itlike this: “I didn’t want to be thought of as heavy metal. To me, Motörhead have more in common with punk.” But Clarke hated the idea. Lemmy hated Clarke for hating the idea. In the end they agreed to compromise – and do the track with Wendy. Clarke didn’t last the first session.

“The trouble is,” he told me years later, “you get to a certain level of fame and it starts to affect the way you’re thinking. The nice thing about not having a pot to piss in, you don’t think. You just get on and do it. I said I’ll have to leave the band, then. They said okay."

There is an extended epilogue to this story, of course. One that would follow Lemmy and ‘Fast’ Eddie Clarke and Phil ‘Philthy Animal’ Taylor to the grave. But Iron Fist marked the end of Motörhead’s golden age. It had lasted just three years.

Motörhead – three syllables: Mo-tör-head. Three Amigos: Lem, Phil and Ed. Three of the greatest rock albums ever made. Iron Fist just isn’t one of them.