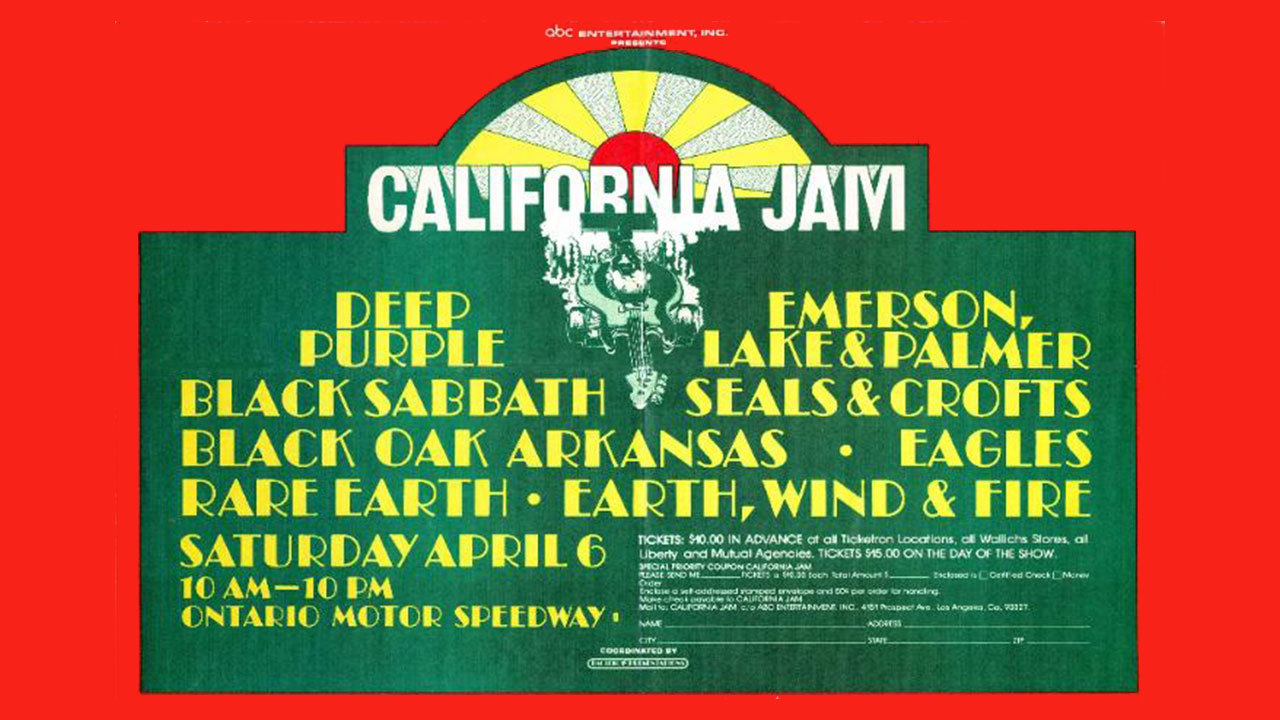

California had been truly rocked – and not in a good way – by the tragic events that occurred at the Altamont Free Concert in 1969 (see page 84). Five years later, the rock world was ready to try again with a brand new festival of highvoltage music. Over 250,000 people descended upon the Ontario Motor Speedway in Ontario, California on April 6, 1974 to attend what had been billed simply as the California Jam.

Boasting an eight band line-up; Rare Earth, Earth, Wind & Fire, the Eagles, Seals & Crofts, Black Oak Arkansas, Black Sabbath, Deep Purple Mk III and headliners Emerson, Lake & Palmer, the first of the two California Jams would prove to be a mammoth affair.

The genesis of the festival was an unusual one. The giant American TV network ABC had a long-running show called In Concert, a programme which captured bands of the day live on stage. It was a groundbreaking idea, since the show was simultaneously broadcast live on FM radio.

One thing led to another, and the executives at ABC turned to In Concert producer Don E Branker and suggested that they would like to host a rock’n’roll festival in California and broadcast it. Branker had had experience in promoting rock shows (primarily on the East coast of the US), and he thought that the Ontario Speedway, located about 50 miles outside of Los Angeles, might prove the perfect location to resurrect the Californian rock festival.

Along with his fellow co-producers Lenny Stogel (who died in an aeroplane accident in 1979) and Sandy Feldman, Branker started to investigate the feasibility of a festival at the speedway.

“We went out to Ontario,” Branker told DJ Mike Stark earlier this year. “And we told them that we wanted to put on a music show. The truth of the matter is that we didn’t say the word ‘festival’, since that was a dirty word after Altamont and Woodstock. And we told them that we wanted to put on acts like the Jackson 5 and the Osmonds, and that it would only be that kinda show.”

The subterfuge worked, and ABC and the producers were granted the requisite permits to arrange the “music show”.

“We then went back three weeks later and told them, ‘Well, we couldn’t get those acts, but we have got Deep Purple, Black Sabbath and Emerson Lake & Palmer,” laughed Branker. “Luckily the police chief out there had never heard of them and he said ‘OK, that sounds fine.’ Later on, he learned that Deep Purple and Black Sabbath were blacklisted, that they were kinda rebellious.”

It was too late though, the permits were issued and the show went ahead as planned. Thankfully, the police chief’s fears were unwarranted and the day passed peacefully. Crowd control was something that was foremost in the promoter’s mind, as Lenny Stogel recalled shortly before his death. “When I knew I was putting on a show for 200,000 young people, I didn’t want anything popping off unexpected. I wanted to be in total control and know exactly what was happening that moment and what would be happening in the next few hours. Two hundred thousand kids was a big responsibility. I used to get a funny feeling in my stomach whenever I thought about it. I had to be in control – for the preservation of my sanity.”

But that didn’t mean that the first Jam was uneventful. And despite Stogel wanting to be in control, that didn’t mean there weren’t gatecrashers.

The first notable happening – for a rock show at least – was that opening act Rare Earth actually took to the stage 15 minutes ahead of schedule at 9.45am.

Emerson Lake & Palmer may have been the headline band, but it was a newly invigorated Deep Purple who were the scene stealers of the day. The official attendance figure of California Jam was 250,000 but “there were maybe 350,000 or 400,000 people there altogether. The fences came down and they all rushed in,” recalls Glenn Hughes, who joined Purple as bassist/vocalist in 1973. “The California Jam was really, really huge. It was a great moment for us.”

As it was their brainchild, major portions of the California Jam were broadcast live on America’s ABC TV channel. The network took a gamble on rock and managed to get four special programmes out of it. Purple’s performance was truly sensational, and clearly won ABC ratings points.

Fuelled by backstage aggravation, their set climaxed in an orgy of destruction by guitarist Ritchie Blackmore. As the epic Space Truckin’ came to a close, he smashed his Fender Stratocaster repeatedly into a camera operator’s lens. He then went on to destroy several more guitars before a huge explosion in his Marshall stacks set his hair on fire.

“It went a bit too far,” remembers David Coverdale, who was plucked from obscurity to become Purple’s vocalist for the Burn album.

“There was too much explosive. It looks great, I agree, but Ritchie got burned. Thankfully it was nothing too serious.”

It did look impressive though, and unequivocally made them band of the day. Footage from Purple’s performance has subsequently been released on DVD. “I love playing in front of a lot of people,” says Hughes. “You can see that from the DVD footage. I was ready for that. I was born to play the California Jam.”

“When I saw the DVD I realised I learned shitloads from that performance,” added Coverdale. “It helped set me on my way with Whitesnake.”

There was also something very unusual about Coverdale’s performance that day. Not in terms of his singing, but rather what he had in his pocket.

“I remember having a million dollar cheque in the arse pocket of my jeans when we headlined the California Jam. Because I was on camera the whole time I thought that was the safest place to keep it. It was a lot of money in those days.”

The day was split very deliberately into two halves, the first four bands on the bill were mellower, almost pop-based groups. And as the day progressed, the heavier and louder the music got.

In the first batch of four, you may have noticed that there was a small band that went by the name of the Eagles. In 1974, they were little more than a fledgling group, and the California Jam would be one of the very few performances when the soft rock band would play with Jackson Browne on keyboards.

It took the organisers three weeks of preparation for California Jam – the Ontario Speedway was a virtually empty swathe of land. Everything had to be brought in especially for the event. Power, water, staging, the whole lot. Given the hi-tech nature of the show – and the fact that it was being done especially for broadcast, many considerations were made that have since become the template for large festival dates.

Realising that an idle crowd is a potentially dangerous crowd, the organisers needed a method by which the transition between bands on stage was as quick and seamless as possible. As part of a ground-breaking idea, sections of the stage were mounted on railway tracks, enabling portions of it to be moved into position with ease (and in super quick time). In fact, turnaround time between bands throughout the day had been kept to about ten minutes. All was going swimmingly until Sabbath came off the stage after their amazing performance.

“English acts are very competitive,” explained Don Branker. “It goes back to the days when they used to play the same clubs, and Sabbath and Purple always had a rivalry because they were both at the beginning of heavy metal.”

Deep Purple had decided that they didn’t want to go on stage until after darkness had fallen, as they had a few surprises for the promoter. Namely, they had pyrotechnics ready to go. And they couldn’t stick the idea of being upstaged by Ozzy Osbourne and his band of doom merchants.

- Deep Purple: 50 years in, where will the adventure take them next?

- Weeley's On Fire: Hell's Angels and flaming fields at the 'British Woodstock'

- Killing yourself to live: how Black Sabbath survived the 70s

With California Jam being a success – it was the largest-grossing concert to date – the most natural idea was to organise a follow-up. And on March 18, 1978, the largest sound system that had ever been built for a festival was cranked up and ready to go.

Using a similar formula of its predecessor, California Jam II revolved around an nine-band bill. This time around it was the turn of Ted Nugent, Aerosmith, Heart, Foreigner, Dave Mason, Bob Welch – with special guests Stevie Nicks and Mick Fleetwood, Frank Marino & Mahogany Rush and Rubicon.

It looked great on paper, but there was one thing beyond the promoters’s control that threatened to marr the second Cali Jam – an uncustomary glitch in the glorious California sunshine. For three consecutive weekends prior to the Jam, southern California had been struck with rain. Lots and lots of rain. And as any veteran of British festivals will confirm, rain can have a nasty habit of spoiling even the greatest of events. However, once again the gods were on the side of rock’n’roll, and for that single Saturday in a rainy year, the clouds kept their peace.

The staging was configured that while one band was playing, another could be prepared to minimise the time between band switchover. Once again, the organisers reckoned on about a quarter of a million people in attendance at the gig. Officially at least. The bands, however, thought otherwise.

“It was just huge,” Heart’s Ann Wilson recalled in 1989. “There must have been about 350,000 people there. It was like standing in the middle of a small city. I’d never seen anything like it.”

In terms of catching the public’s imagination, the bill for California Jam II was perfect, as Branker told Stark. “We were real lucky,” he explained. “The top four acts on that show were Aerosmith, Ted Nugent, Foreigner and Heart. We booked the show in December and by the time the show came round, four of the top five albums in the nation were Foreigner’s first album, Heart’s first album, Nugent’s Cat Scratch Fever album and Draw The Line from Aerosmith, so we really lucked into that being so hot at the time.”

Luck may have had something to do with it, but there can be no denying that both California Jams were examples of how a huge outdoor rock festival could (and should) be run. And the artists agreed.

“I’m lost for words. The kids blow my mind. It was like an ocean of people out there,” Ozzy told a radio interviewer after Sabbath came off stage at the first Jam. “When people’s arms went up in the air… I’m just knocked out by it all. If only every open-air rock show could go half as good as this. This is where it’s at, y’know…”