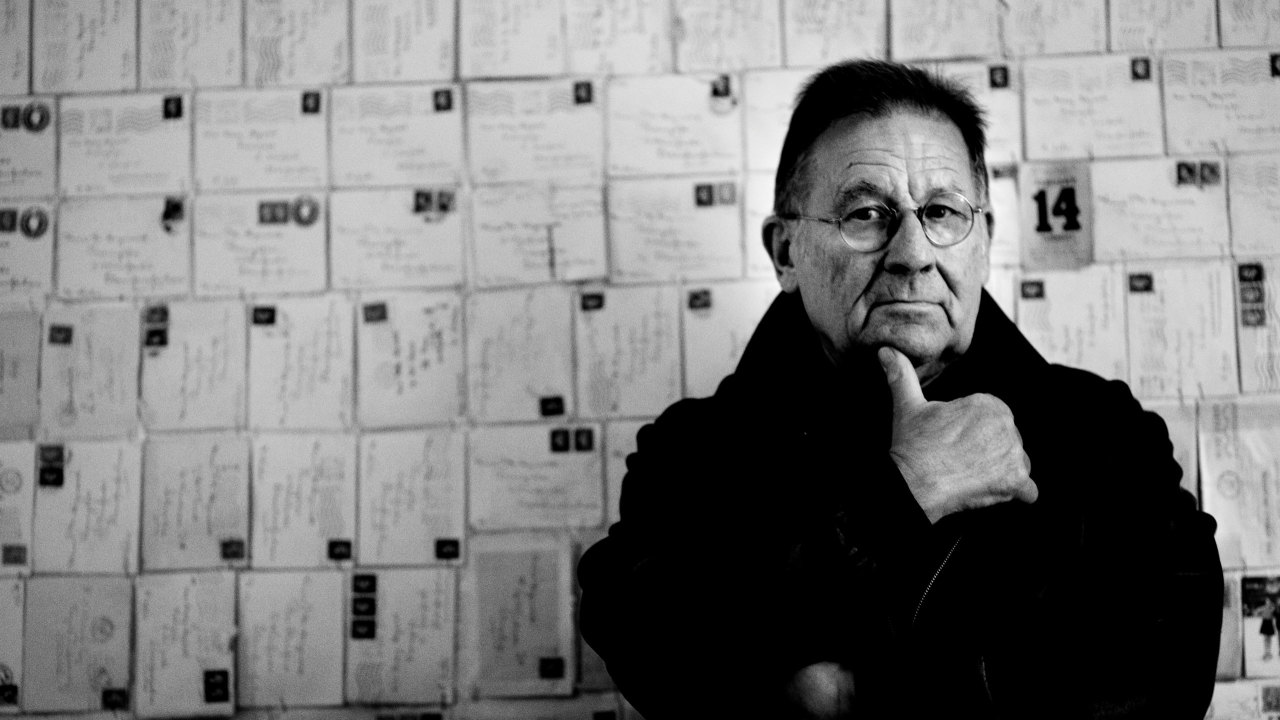

“I was reading a poem before you called,” says Irmin Schmidt.

The 78-year-old keyboard player, best known for his work as part of Germany’s aural explorers Can, is in a reflective mood as we settle down to talk about the release of Electro Violet, a 12-disc box set that collects his collaborations and solo work. The poet in question is Rolf Dieter Brinkmann, a visitor to Can’s studio space in Cologne in the late 60s and 70s. “He was killed in a hit-and-run accident while crossing the street in London in 1975. He was a wonderful poet, and would have become really big had he lived.” A line from Brinkmann’s Ice Water On Guadalupe Strasse cycle of poems seems to capture something of Schmidt’s own life and approach to a career that has resolutely gone against expectations:

‘It is

the gaps, the spaces,

that what you did not do,

what you omitted, left alone

that opened the space

_

for dreaming.’_

Schmidt’s dreaming saw him move away from his studies under Karlheinz Stockhausen and György Ligeti, and the world of contemporary classical music, to late 60s Cologne and the formation of Can. Having spent more than a decade in the group, when it came to making his first solo record, a soundtrack for the 1978 film, Messer Im Kopf, Schmidt admits to being daunted at the prospect. “I was in the Can studio all alone which felt very strange somehow. I needed to prove that I could do it on my own. It felt quite adventurous and very liberating.” From there, Schmidt restarted a process of sometimes startling reinventions of himself and his identity as a composer and player that had to some extent been held in check within Can. After his collaboration with Swiss saxophonist, Bruno Spoerri and sound engineer Ron Kurz on 1981’s Toy Planet, and continuing to provide numerous film scores, the man most associated with some of the most perplexing avant-garde ruminations in Can turned his hand to writing songs. “In Can, we’d develop the material together. Even if someone was responsible for leading that, it was always in ‘the group’. With Musk At Dusk (1987) and Impossible Holidays (1991) I decided I wanted to write all the music for the songs myself. Again, it was another angle, something I’d not done before. I’d done a little singing in Can and decided I wanted to try singing all the songs. It was daunting but it was a lot of fun.”

Alongside Schmidt’s tremulous sprechgesang vocal style, a defining feature of these albums is the way in which his acoustic piano playing is brought to the fore. Although a grand piano was ever-present in the Can studios, it was only occasionally used. Veteran UK jazz pianist Stan Tracey would sometimes refer to his instrument as his “old adversary”. Although such a description intrigues him, it’s not a viewpoint he shares. “No, I would describe my relationship with the piano as a love affair.” It’s a love stretching back to his childhood home, where his parents both played. Yet his own desire to play as a child was put on hold after being evacuated from Berlin during the Second World War. “After the war we lost everything. Our house was totally gone. I managed to take some lessons when I was 12 but to practice in the house of a stranger, so to speak, you feel a little uncomfortable. It wasn’t until I was 15 and we moved into a better place, that’s when I started working like mad. It was really my instrument and although getting my first piano when I was 15 was really quite late, it was something I had longed for, it was like falling in love.” Schmidt also confirms his piano playing provides a therapeutic outlet. “When I’m in a bad mood or depressed, I go to the piano and really work on a piece of Chopin or Brahms for four or five hours and then any depression or bad feeling is gone. It makes me feel sane and lucky!”

Consistent with his inclination to present different aspects of his musical personality, in 2000 he released Gormenghast, his most ambitious work to date. It was, he says, as though his entire career had been leading him up to the point of writing a three-hour opera based on Mervyn Peake’s novel describing a stagnant society bedevilled with corruption and manipulative forces. The book had been introduced to him by his friend and lyricist, Duncan Fallowell. “The novel is a metaphor. It’s not just a fantasy story but one which reads like a commentary upon the state of the world. Gormenghast was me saying, ‘I want to write a really big score and create a work in which I can unite all these styles of the 20th century but from a new angle.’ I was using classical singers performing against really fierce rock rhythms, using the orchestra in a lyrical manner, uniting these opposing styles in a new soundworld. The most amazing thing for me was that in the beginning these opera singers were frightened to be asked to do something that they’d not done before - to sing every night to a given rhythm on a tape. Because that rhythm didn’t alter each night, they thought the music didn’t live or breathe. They thought that as a rock musician I might not be able to write for voices, but before Can I worked in an opera house where I taught singing for actors and actresses, so I knew a lot about voices. After working with them, they loved singing it. The album really just presents an excerpt of the full opera. I would love to get all the music released but I don’t think that’s possible at the moment.”

If you’ve created music all your life you want that to exist in the world. It’s there.

Having been awarded a French knighthood for his contribution to the arts in 2015, Schmidt has new projects, including contributing to a biography of Can and collaborating with Cologne-based composer Gregor Schwellenbach on scoring Can and solo pieces for an orchestra. “Again, these things are totally new for me. It’s exciting.” Schmidt agrees that 2012’s The Lost Tapes Can box set and Electro Violet are about curating his musical history and legacy for posterity. “If you’ve created music all your life you want that to exist in the world. It’s there. It’s like a house you build for yourself. It’s your life that’s there in front of you. You can look at it and say, ‘that’s what I made.’”

Taken together with the Can box, it represents a remarkably diverse and fascinating body of work. He happily admits that the idea for Electro Violet wasn’t his but that of his wife of 58 years, Hildegard, who also happens to be his manager, “And if Hildegard wants to have something, she gets it,” he adds wryly.

Electro Violet is out now on Mute/Spoon. See www.irminschmidt.com for more info. Records.