This article first appeared in The Blues #5, February 2013.

Once upon a time, half a century ago in the early 1960s, as the first tender shoots of what would eventually become the British Blues Boom began, cautiously but hopefully, to poke their shaggy little heads towards the surface, it seemed blindingly obvious to all concerned what qualified – or, more precisely, what didn’t qualify – as ‘authentic blues’.

To wit: a particular and specific music created and performed by black Americans mostly born in the Deep South (as it was then known) during the first few decades of the 20th century, many of whom later migrated to Midwest industrial centres such as Chicago or Detroit.

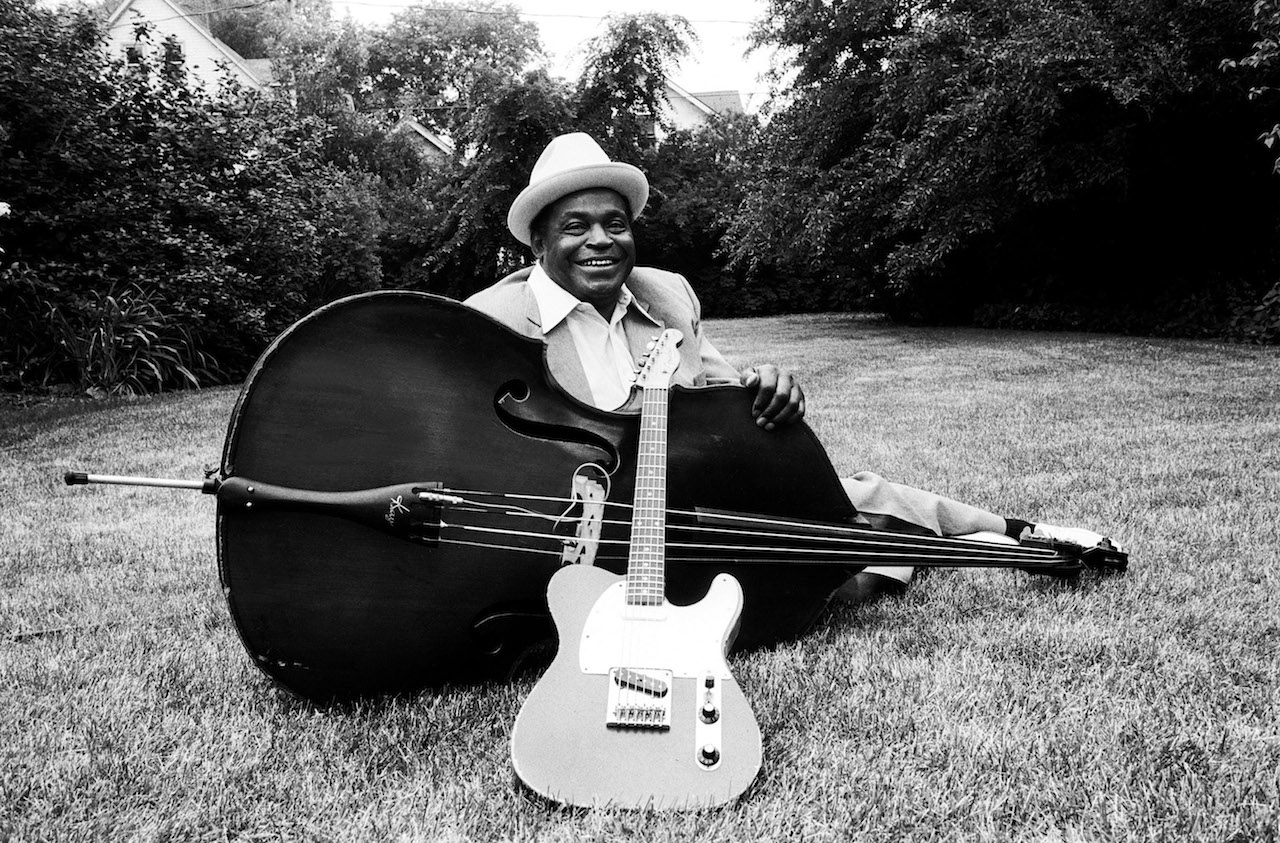

You know: the likes of Muddy Waters, John Lee Hooker, Howlin’ Wolf, Little Walter, Sonny Boy Williamson, Willie Dixon, Elmore James, Otis Spann, Big Mama Thornton and Jimmy Reed, with Chuck Berry and Bo Diddley at the pop/rockier end of the spectrum, and the likes of T-Bone Walker and B.B. King among the more sophisticated. Or the pre-war acoustic maestri like Son House, Skip James, Lonnie Johnson, Big Bill Broonzy, Sonny Terry & Brownie McGhee. The spectral Robert Johnson. Otis Rush, Buddy Guy and the other two of the Three Kings.

Basically: the guys who inspired the white boys, who wrote and performed the original versions of the songs they covered (and sometimes even credited).

The Real Guys who played the Real Blues. Everybody knew who they were and what that was: it was defined sociologically (via race and geographical origin), idiomatically (based on the templates of all those great records and their licks, scales, song structures, instrumentation and vocal timbres) and emotionally (in terms of the power and intensity of the feelings those artists expressed).

That was then. How about now in 2013? Most of those Real Guys are gone, leaving B.B. King and Buddy Guy as the last men standing (or, in B.B.’s case, sitting). Check it: Muddy Waters, Albert and Freddie King, Albert Collins, Wolf, John Lee, Sonny Boy, Jimmy Reed, Bo, Walter, Willie, Spann, Junior Wells, T-Bone Walker, Etta James and Koko Taylor (let alone Skip and Son and Mississippi John Hurt) are merely a few of the great bluesmen (and women) who’ve left the set. Bobby Bland and Otis Rush are still with us (albeit in virtual retirement), as are Taj Mahal and Robert Cray, but the latter pair are, respectively, contemporaries of the Stones and Stevie Ray Vaughan, rather than of Muddy or B.B.

As long ago as 1974, Albert King cut a Stax track called The Blues Don’t Change. Whatever the lyric might have asserted, the music – which, if you removed The Big A’s unmistakeable voice and guitar, would have fitted seamlessly behind the label’s heaviest commercial hitter of the time, Isaac Hayes – said something entirely different. Or maybe that was the point: that there was an aspect to the blues which was timeless and eternal, retaining its ultimate ethos and essence whatever the context in which it was placed. The same wine in different bottles; the same body in different clothes.

The fact remains, for all but the genre’s biggest stars, the popularity of the blues with its classic traditional constituency – the black working-class, urban and rural – had been in decline since the late 1950s, supplanted by R&B and soul. And, by the same token, the catchment pool of young black musicians prepared to dedicate themselves to playing the blues was also shrinking. It was the early 60s discovery of the blues by a young, white, post-Stones audience which revitalised many careers (as most of the artists themselves gratefully acknowledged) and refreshed the idiom, but at a price: from then on, it was the tastes of that audience – not to mention its numerical superiority and greater spending power – which not only supported but defined, and finally dictated, the blues economy.

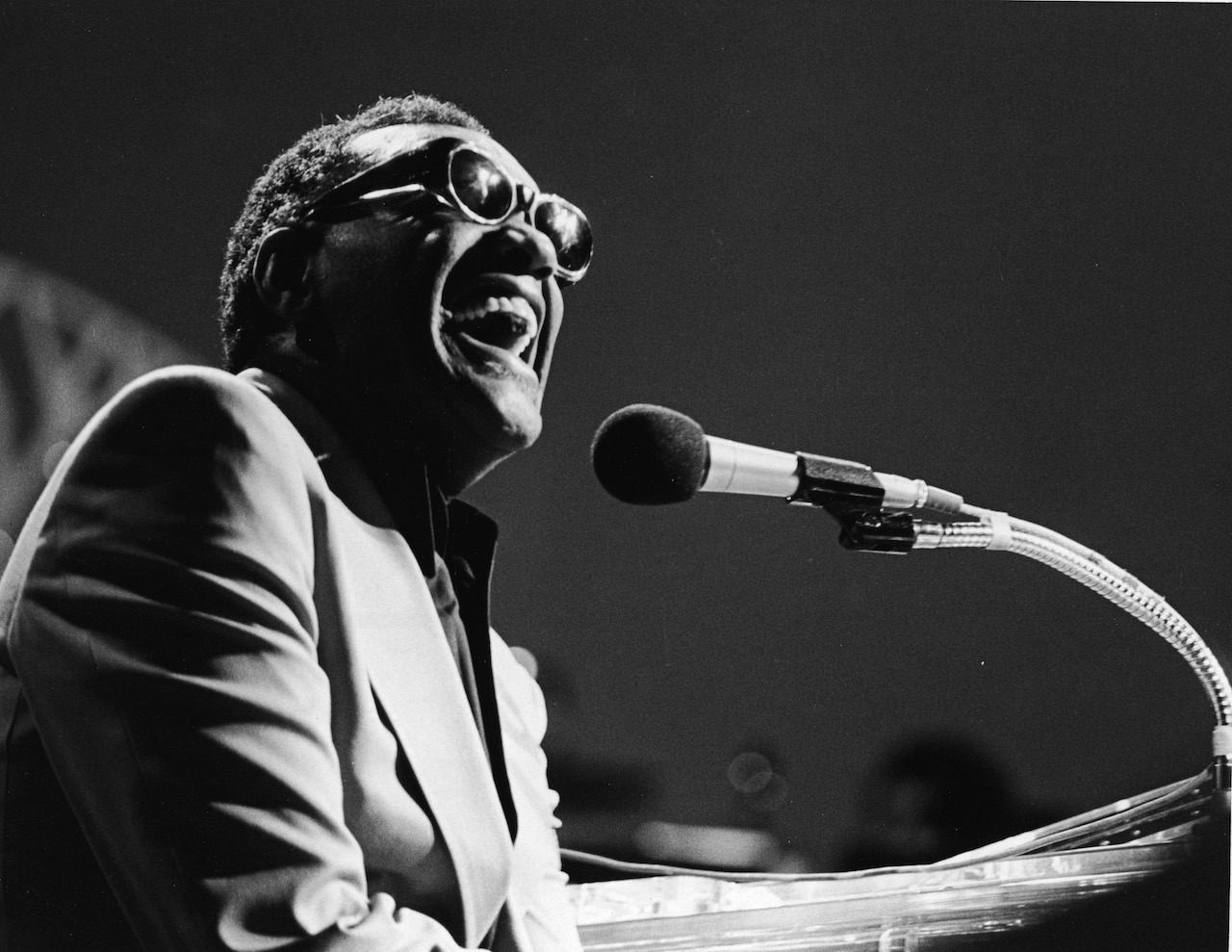

Throughout the music’s history, a wide variety of blues styles have always co-existed. Sophisticated urban styles bordering on jazz or soul sat side by side with defiantly rustic idioms which retained their rural roots, even after moving to the cities and plugging in; the swing-band-plus-electric-guitar tradition established by T-Bone Walker and exemplified by B.B. King complementing the electric downhome of Muddy and Wolf (before fusing in the South Side stylings of Buddy Guy and Otis Rush). Ray Charles fused the content and vibe of the blues with the structures and intensity of gospel, and in the process he in effect invented soul music.

So, what does ‘authentic blues’ mean today in terms of a contemporary music? Is there still such a thing as ‘authentic blues’ being played outside small towns in the US South any more? If so, what is it and where is it? If not… does it actually matter, as long as the music which is being played today under the blues banner can rock your body and move your soul, while retaining trace elements of the original flavour?

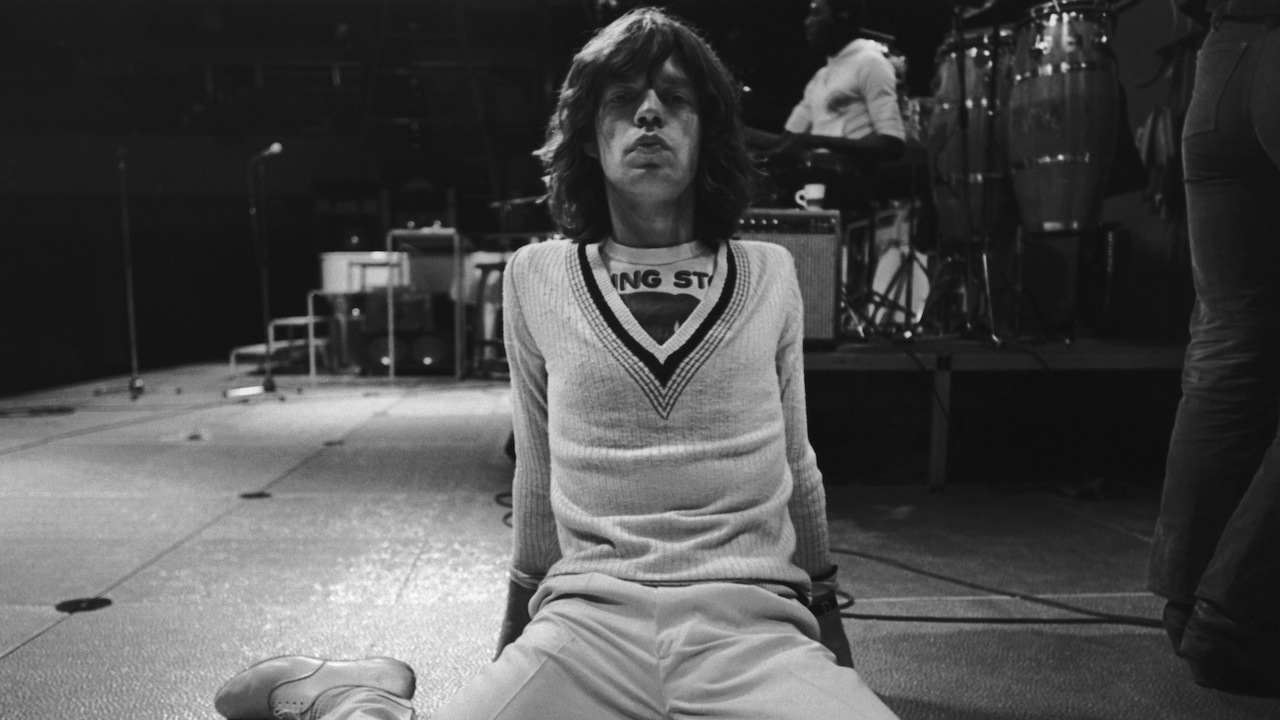

Your humble servant has been asking himself this question for awhile now. Like many of my g-g-g-generation (and subsequent ones), the Stones provided my introduction to the music, and it was their championing of the Chess stars which motivated my own explorations. Increasing exposure to the pop-blues-rock of the time (not just the Stones, but Yardbirds, Animals, Manfred Mann, et al) running in parallel with discovery of more and more of the Real Guys. Similarly, Mayall, Clapton and Green led legions towards the Three Kings. And so on. All eagerly consumed alongside quality chart pop – anything from The Beatles and Dusty Springfield to The Kinks and The ‘Oo; Stax, Atlantic and Motown, bits of jazz and folk … all mingling in a teenage head. I was passionate about Howlin’ Wolf long before I knew Charley Patton even existed; about Muddy Waters while still in total ignorance of Son House.

For the musicians who made up those British bands, the classic records were hard to find, and reliable information about the artists who created them harder still. They were attempting to understand and master the music from a geographical distance of thousands of miles, and a cultural distance almost immeasurably more vast. Unlike, say, Mike Bloomfield and Paul Butterfield in Chicago, or Johnny Winter in Texas, they couldn’t simply cross town and hear, meet and – once initial suspicions were overcome – jam with and be tutored by the blues maestri. The Brits were forced to learn what they could from records and the occasional touring blues stars, and make up the rest: to join the dots by imagination and invention. Through those creative misunderstandings of their source material, a new music – blues rock – was born. I fell in love with both the ‘real’ and the ‘imagined’ blues.

- The Rolling Stones – 50 Years Of Rock'n'roll

- Johnny Winter: Life Inside His Final Tour

- John Mayall's Bluesbreakers with Eric Clapton is 50: how they made the Beano

- Hubert Sumlin: Howlin' Wolf's Right Hand Man

As a result, sometimes I want to hear Crossroads performed by Robert Johnson, but at other times I want to hear Cream do it. Sometimes my ears yearn for Howlin’ Wolf singing I Ain’t Superstitious, and sometimes for Rod Stewart singing it with Jeff Beck. Sometimes I need Blind Willie Johnson’s monumental Nobody’s Fault But Mine, and at others Led Zeppelin’s, equally monumental, but in an entirely different way. Bo Diddley’s measured, magisterial I’m A Man is magnificent, but so is The Yardbirds’ revved-up, punky take on the same tune. By the same token, Sonny Boy Williamson II’s Don’t Start Me Talkin’ is a thing of joy and beauty, and will remain so forever, but once in a while it’s fun to hear The New York Dolls rattling through the same tune.

All well and good, right? As Chairman Mao proclaimed in 1957, “Let a hundred flowers bloom and a hundred schools of thought contend.”

Leaving aside whether this was actually what happened in China, the problem would seem to be this: that through sheer weight of numbers – both human and financial, among audiences and musicians alike blues rock has become the dominant form, not annihilating or destroying the music’s myriad other forms, but in effect shouldering them from centre-stage. And centre-stage is, mostly, where the money is.

If that claim below was true when Otis Rush first made it, it’s far truer today, when young African-Americans have about as much interest in the arcane crafts of harp and slide as their British contemporaries do in morris dancing, and for pretty much the same reasons.

There’s absolutely no doubt that the blues was the creation of African-Americans existing in a certain place at a certain point in time. In 1962 they were, barring a few lonely outposts elsewhere, the only people who played it and who knew how to play it right, and they also represented most of the people who listened to it. In 2013, a full half-century on, the music is global. It’s enjoyed and performed by people all over the world and, inevitably, both listeners and players bring to the music tastes and influences from their own locations in space, time and culture.

Nevertheless, no matter who originated it, music belongs, in a wider sense, to those who play it and those who listen to it. To insist that the great classical repertoires somehow still ‘belong’ primarily to Europeans would be churlish and ethnocentric, not to mention doing a massive disservice to musicians of other cultures who have found their souls stirred by the music of Beethoven, Bach and Mozart, and whose interpretations of their immortal compositions are undeniably world-class.

So at what point should we demand that the music stand still and be flash-frozen or freeze-dried? In 1948, when Muddy Waters and John Lee Hooker had their first hits? Or 1958? That was the year Muddy first showed up in the UK with his Telecaster, only to be booed by rigid old folkies and jazzers who felt that the Real True Blues had to be rural and acoustic, untainted by the vulgar degeneracy of electricity and the city.

We laughed at them for being too narrow-minded to appreciate the glories of Southside Chicago’s electric downhome. Have we now met the enemy, and found that it’s us? (Or 1964, when B.B. cut Live At The Regal? How about 1966, when Albert King signed to Stax? Or 1968, the year of B.B.’s string-l laden, funk-grooved The Thrill Is Gone?).

Earlier on we mentioned the old 1962 tripartite qualification for blues authenticity: sociological, stylistic and emotional. Now let’s check it out again. Sociological? Forget it. The world has changed, and the blues has changed with it, as any living music must. Stylistic? Even those for whom the blues is the centre of the musical universe must acknowledge that it’s nevertheless surrounded by other musics – jazz, rock, soul, funk, country and, latterly, hip-hop, to name but half-a-dozen – and musics can’t stop listening and talking to each other any more than musicians can. It’s inevitable and appropriate that older styles, preserved because, let’s face it, they’re still groovy and eminently worth preserving, will find newer ones coming into being around them.

The blues has to mean something. It has to make you feel stuff. It has to remain a practical musical tool for enabling musicians and listeners alike to confront pain and worry and come away feeling better. If it’s just an excuse for being a little bit flash on your Strat over some simple chord changes – then that’s what’s not the blues… just a two-dimensional, cardboard cut-out of it.

I want guys such as Otis Grand – an outspoken blues purist – to keep playing his music exactly the way he wants to. But I also want Joe Bonamassa – and the geography teachers who bring their harps and guitars to their local’s weekend blues jam for an invigorating canter ’round the old 12-bar corral – to be able to do likewise. As long as what they create still retains that flavour, that power and that unique emotional quality that so captivated me when I was a kid encountering first the Stones’ music and then Muddy, John Lee, Buddy, B.B. and all the other Real Guys. As long as the players are feelin’ it, and able to communicate some of what they’re feelin’.

The bottom line: now most of the Olde Masters are gone, there’s just us left – the listeners and musicians of today, all over the world. We all come to the blues from our own individual musical and cultural starting points. We bring our own stuff to the fundamentals of the music; we use it to express the truths of who we are and we respond to it when it speaks, with sufficient eloquence and conviction, to our most authentic inner selves.

Black America – specifically, its most oppressed elements – did indeed create the blues for itself, but it’s since been passed on to the world. Now it’s up to those of us, irrespective of age, ethnicity or national origin, who love it, who’ve been touched and moved by it, both to make it our own and to ensure that it prospers, grows and reflects the world as it is, not just as it was.

At this point in time and space, the blues is – and will be – what we, musicians and listeners alike, make it. It’s in our hands. May we treat it with the love, respect and gratitude it so richly deserves, and – no matter how much it may change and grow – may it live for ever, bringing both solace and rockin’ good times to generations yet unborn.