The Whisky A Go Go, West Hollywood, May 1966, after midnight. Jac Holzman, 35-year-old owner of Elektra Records, just arrived on the red-eye from New York, is blearily checking out this new band that club manager Ronnie Haran keeps bugging him about. They’re called The Doors, and Ronnie says they are far out, man, trippy. And they have a to-die-for 22-year-old singer that even the boys want to lick the face of.

Holzman, who has recently signed the band Love – whose lysergically depth-charged debut album he also produced – has absolutely no interest in signing another psychedelic rock band. But Love’s leader, Arthur Lee, has also hipped him to these new cats, The Doors, and so Holzman feels obliged to at least give them the once-over.

Holzman, though, is not impressed by The Doors.

“Morrison made no impression whatsoever,” he would tell me years later. “There was nothing that tagged him as special.”

Indeed, Holzman recalls being so underwhelmed he walked out mid-set. But then Haran insisted he come back the following night. Jim was acting up, she said, refusing to put on a show for the record company ‘suit’ Arthur Lee had told him was in the audience. Which is how Holzman found himself back at the Whisky the following night, watching The Doors all over again. But still no eureka moment. Just a band bashing out a terse form of blues with vague classical and jazz leanings.

Nevertheless, everyone Holzman talked to in LA now seemed to have a bead on The Doors. When Barry Friedman, the former Beatles publicist who had recently begun managing one of LA’s other hottest new bands, Buffalo Springfield, started babbling about them too, Holzman went back to the Whisky the next night – and the next.

“The question I ask myself when I look at any artist is: is this music something I haven’t heard before?” explains Holzman. “Well, it wasn’t the first two or three nights but it was the last night. Sometimes there are songs that are like Rosetta Stones, and once I heard [their version of] Alabama Song (Whisky Bar), I got the rest of it. All the gaps just filled in.”

Because The Doors “had taken something that was so off the wall” – a 1925 song written for Bertolt Brecht and set to music by Kurt Weill – “and converted it into a song that could appear on a rock album,” Holzman finally got what The Doors’ monochromatic, mock-Weimar cabaret sound was all about. Where every other band in 1966 was extolling a wide-eyed gambol through the acid-kissed prism of love-love-love, The Doors appeared as the antithesis to all that, the dark angel come to eat its own children. Fuck its own mother; kill its own father.

Holzman approached the band in their dressing room at the Whisky that same night.

“When I heard that fourth night I knew this was a great band,” he says. “I wanted to be where nobody else was yet.”

Which was exactly where Morrison and The Doors lay in wait for Holzman and the rest of the world to find them.

In truth, the four members of The Doors could not believe their luck. They had been turned down by every record company on the West Coast, their only previous deal with Columbia having petered out before they’d even recorded anything, and though they didn’t know it yet they were mere days away from being fired from the only steady gig they had.

If Jac Holzman had walked into their dressing room wearing a Santa Claus outfit and carrying a sackful of cash, he could not have made a more welcoming impression. Nevertheless, true to form, Jim Morrison urged the others – keyboardist Ray Manzarek, guitarist Robby Krieger and drummer John Densmore – to play it cool. As a result, says Holzman, he was forced to go “through the agony of a summer trying to nurse them toward signing [the deal], which did not occur until several months later.”

Ronnie Haran, who Morrison was then living with, advised the band to get a good lawyer, suggesting they use hers – but they turned down the offer. This caused bad blood and Jim was forced to move out of Ronnie’s apartment. As he was leaving, he told her, “I’ll be dead in two years.” But Jim was always saying stuff like that.

In the end they followed the advice of Robby’s father, Stu Krieger, who put them together with the deliciously named Max Fink, a big-cigar Hollywood attorney who knew his way around the back alleys of LA as well as he did its glitzy front offices.

Fink ate out-of-town New York suits like Holzman for breakfast – or told The Doors he did – and set about his work with relish, drafting a letter of agreement that everybody signed on August 20, allowing The Doors and Elektra to proceed with recording an album, but delaying any long-term deal until the contract was finally agreed in November.

Any other record company chief would have walked away. Fortunately for The Doors, Jac Holzman was not any other record company chief. The eldest son of a Park Avenue doctor, Jac was a super-smart boy who studied Descartes at college, and who would bring his gift for minute analysis and almost geometrical calculation to all his future dealings.

“I wanted people to think of Elektra as different to the others,” he says. Well, they certainly did that. By the time he met The Doors, Holzman’s Elektra had become one of the leading independent record labels in the world. Three weeks later The Doors were ensconced in Sunset Sound Recorders, a bare-knuckles Hollywood recording facility purpose-built by Walt Disney in 1958 to record the soundtracks to Mary Poppins and 101 Dalmatians.

Originally, Holzman had considered producing The Doors’ debut album himself. But after meeting Jim he turned the job over to his right-hand man, the producer Paul A Rothchild.

“I loved the studio, but I thought Paul knew more than I did about how to do this kind of band,” Holzman explained. “Ray and Jim were super-smart, and you needed a guy who was as well read as they were, and Paul was that. I thought he could really whip them into shape.”

At 31, Rothchild was just old enough to exert authority over the group, just young enough to be hip to their trip. A classically trained musician from New Jersey, who had been groomed for success by his mother, a singer with the Metropolitan Opera, Rothchild had trained under the tutelage of the conductor Bruno Walter. Swept up by the folk revival, he found himself in Cambridge, Massachusetts, on the board of Club 47, the small but significant venue in the Harvard Square area of Cambridge where Joan Baez gave her very first concert, barefoot, in 1958.

The next few years found Rothchild working as a Boston-area record distributor, while also trying to make his mark as a producer. By 1964, Rothchild had relocated to New York, where he hooked up with fellow folk-rock enthusiast Jac Holzman and produced his first albums for Elektra Records.

Clad in regulation skintight jeans, even tighter T-shirt or often as not no shirt at all, his long hair tied in a ponytail to distract attention from the fact that he was already balding, Rothchild would come striding through the studio door, avoiding all eye contact until he was settled behind the console, where he would snap open his briefcase. “The briefcase was famous,” says Holzman. “It held everything he might possibly need: pitch pipe, the latest gadgets, cigarettes, whatever drug was up for the evening.”

Paul was a loner, super-focused and as self-absorbed as any artist. “He could do a ‘Hey man’ to the artist,” as Holzman put it. Plus, Paul owed Jac big – and despite reservations gave in when Jac reminded him of it. Rothchild had just been released from prison after serving eight months of a two-year sentence for possession of marijuana – several suitcases full of the stuff. While Paul had been incarcerated, Jac had given his wife part-time work at Elektra, to help her meet the bills.

First, though, Rothchild insisted he work with the band at some intense pre-production rehearsals. “The arrangements and the way things went, were a lot Paul Rothchild,” Holzman says. The prime example was Light My Fire, which the stickler-for-detail producer sculpted from the musical miasma of its sprawling live incarnation into something with real shape and gravitas.

Even though they were there with Rothchild – and his engineer Bruce Botnick, who had previously worked with the producer on Tim Buckley’s first album – for less than a week, The Doors “owned Studio B” at Sunset Sound. Yet the band was so paranoid about being ripped off, at the end of every session the doors would be double-locked. Dropping in on the sessions, Holzman was also convinced this was precious cargo.

“It was for Elektra Records, so I knew it was going be different,” Botnick now recalls. While Rothchild had the “vision thing” – converting an extremely functional four-track facility into a late-night netherworld where Jim and the band could let their nocturnal spirits roam, even as he obliged them to do different takes, teasing the best performances out of them – the 23-year-old Botnick’s job was to be Mr Fixit, getting the set-up right, keeping the tape rolling, placing bafflers and mics, helping Paul fly the faders, coming up with the little extras that might make the difference.

“Jim was in the vocal booth. The guys were in the studio itself. It’s 10 feet apart at the most. They could see one another. I always kept the lights dark in the studio. You know, they needed to have that. Down to screwing in some red light bulbs in the studio that glowed like that.”

The first day the band arrived in the studio, Botnick recalls, “they had pretty much the first two albums ready to go. The thought that Paul had was that we were to be invisible – to allow them to capture the magic of The Doors as you went to hear them.” He adds: “They were totally different than anything else I was recording. I was recording the Beach Boys, The Turtles, The Ventures… and The Doors were totally different, it was the beginning of that era of American sixties music.”

Bassist Larry Knechtel, part of the top LA-based session outfit the Wrecking Crew, who had played on dozens of hit records throughout the 60s, was hired to play on six of the album’s eventual 11 tracks, with Ray handling the others on keyboard bass. Only three of the studio’s four tracks of tape were actually used – drums and bass on one, guitar and keyboards on another, and Jim’s vocals on the third – with the fourth track kept back for overdubs.

Apart from the album’s two cornerstone tracks – the seven-minute-plus Light My Fire and the nearly 12-minute The End – most of the tracks were less than three minutes long. But then, in truth, despite regularly being hailed since as one of the all-time great rock debuts, the first Doors album was a mixed bag of disposable 60s pop and a truly gothic form of rock, with layers of Indian raga, jazz stylings and neo-classical pretensions.

While tracks like the rousing, call-to-arms opener, Break On Through (To The Other Side) and the genuinely spaced-out Crystal Ship, with its, for the times, outlandish opening couplet: ‘Before you slip into, un-con-scious-ness…’, suggested a very different, far more advanced, into-the-night type of rock band than any seen before, others like Soul Kitchen – inspired by the band’s fondness for a cheap and cheerful Venice Beach soul-food joint called Olivia’s – and Twentieth Century Fox – a droolingly stoned play on words, geddit? – are so wincingly à la mode they would have struggled to get on the first Monkees album, also being made that summer.

The painfully peacocking I Looked At You sounds like a Paul Revere & The Raiders B-side. Other tracks, such as End Of The Night – another self-consciously spooky interlude with only its Céline-inspired title to guide it – and the deliriously vacuous Take It As It Comes sound like what they are: side salads for the real steaks on the plate: Light My Fire, with its grandiose Bach-fugue intro and swirling instrumental middle section inspired by John Coltrane’s Olé, and The End, the only truly riveting musical journey into the mystic they make, which, fittingly, closes the album.

Given the inclusion also of two cover songs – their admittedly inspired live reading of Alabama Song (Whisky Bar) – and Jim’s thinly veiled reference to his growing obsession with anal sex, Willie Dixon’s Back Door Man (every groupie on Sunset Strip was now privately complaining about how Jim was pestering them for it) – it seems strange that they didn’t consider including some of the other tracks they already had completed, specifically, the truly transcendent Moonlight Drive and the equally ethereal Indian Summer – or at the very least, if they were looking for a hit, Hello, I Love You. All of which were recorded during the sessions – and would be included on future Doors albums – but passed over when it came to the final sequencing of their debut.

According to Robby Krieger, the beautiful Indian Summer, though it would not be released for another four years, was the first song the band ever fully completed, with Moonlight Drive coming after. But Paul Rothchild had decided they needed more upbeat numbers so Indian Summer got nixed in favour of Back Door Man, and the original version they cut of Moonlight Drive they simply didn’t think was good enough. (Listening to the track on the contemporary re-mastered CD version of the album, released after Rothchild’s death in 1995, it’s hard to disagree.)

“Every day we got something great,” Rothchild would recall. “Jim was out of control on some days, but that was just another aspect of that phenomenon: the Jim Morrison spirit! Because we were recording when Jim was at one of his most insane points, when he was deep into acid.” They would try various different songs, do a few takes then move on to another. They even tried having a go at The End on the first night but it just wasn’t happening. So they got it on the second night instead, shrugged Rothchild.

In fact, the recording of The End, which would eventually roll out to almost 12 minutes in length – unheard of for a rock song at that time – precipitated one of the most oft-told, yet always exaggerated stories from the making of the first Doors album. According to legend, the band was two-thirds of the way through playing the track, just after Jim had turned his on-stage announcement of wanting to fuck his mother into an incoherent yowl, and as he began to dervish around the studio he noticed – oh, the insult! – that Bruce Botnick was watching a small black-and-white TV tuned to a baseball game, which Jim, absolutely furious, smashed to the floor before picking it up and nto the control room, where Botnick and Rothchild sat shocked.

Speaking now, however, Botnick sighs and claims it was a far less dramatic moment. “I don’t know why I did this but I had this Sony TV, a little one, on a stool looking into the control room.”

The Los Angeles Dodgers were playing the St Louis Cardinals with the baseball legend Sandy Koufax pitching. As far as Bruce, who had no idea yet who The Doors were, was concerned, he’d simply brought the TV into work with him to catch the game – with the sound off.

“And in [Jim’s] flying around he knocked it off. It did not explode. It did not catch on fire. He did not pick it up and throw it through the glass as Ray Manzarek said that he did. None of that happened. But he knocked it off and yes it went on the floor, and the tape continued. In between takes I walked out into the studio and got it and turned it off. And then we did a second take. The End comprises two takes and we edited it together – the first half and the second half. For the performance aspect we made the cut. Because everything that happened on that album was based on performance.”

The other flashpoint from those sessions that has since gone down in history has also been exaggerated, according to Botnick: the one in which a fiercely tripping Morrison – on the same night they completed splicing the two best performances of The End together – returned alone to Sunset Sound and proceeded to trash the studio, throwing ashtray-sand over the floor and emptying a fire extinguisher into the mixing console.

According to Botnick, though, this was not merely an act of acid-crazed petulance, but a genuine attempt, albeit with lid flapping wide open, to avert what Morrison saw as a disaster.

“Sunset Sound was an old garage [that had] been converted. It was absorption, brick, absorption, brick… Inside each brick was a light, and that’s where I screwed the red light bulbs.”

After everyone had left the studio that night, Jim had “gone across the street to the Blessed Sacrament, a Catholic Church, and he had an epiphany over there. He came back to the studio and the gate was locked. He climbed over the gate, got in but he couldn’t get in the control room. That was locked. But the studio was open and the red lights were on and he thought it was on fire so he grabbed a fire extinguisher and knocked over the ashtrays that were full of sand and tried to put out the fire.”

Recalling the incident at the time, however, Rothchild said he’d received a phone call from the chick Jim had left the session with, saying Jim had jumped out of her car and was headed back to the studio. When Paul got there Jim was shoeless and shirtless. When Paul asked him what the fuck, he just grinned that slow-burn grin and said: “I want to record.” Paul talked him down and they retired to Jim’s pad, where they spent the rest of the night digging the Stones, Donovan, Howlin’ Wolf… Paul finally escaped around dawn.

As he walked through the door of his Laurel Canyon home his phone was ringing. It was studio owner, Tutti Camarata, apoplectic with rage, saying the studio had been trashed: fire extinguisher foam all over the mixing console, sand from a stand-up ashtray hurled across the room. Also a pair of Jim’s old stinky boots… Did Paul know who they belonged to? Paul said he did not. Then told him wearily to send the bill to Elektra.

In the end, despite the stoned immaculate shenanigans of both band and producer, the first Doors album – simply titled The Doors – took just five days to make. Yet it took five months for Elektra to finally release it. This was almost entirely down to the fact that it took another three months of interminable contractual wrangling between Holzman and Fink before they finally agreed a deal. Jim and Ray had pushed at that point for the album to be released immediately, in time for Christmas. But Jac, the wise old label head, knew better and talked them into allowing Elektra to hold back its release until the new year.

Ray and the rest of the band acquiesced, realising they had no choice in the matter anyway. But Jim threw a tantrum and again needed to be talked down. As Holzman later recalled, even then Jim and the other three members of The Doors were “really two entities: Ray Manzarek–Robby Krieger–John Densmore, and Jim Morrison, separate and apart.”

Morrison was now living in a nine-dollars-a-night room at The Tropicana (‘The Trop’, as Jim called it), the rundown West Hollywood motel where the black-tiled pool had no water and the guests festered, sharing their drugs and cheap wine, bed-hopping and stealing from each other; the kind of low-rent dive where all the musicians that hadn’t yet made it stayed.

Meanwhile, the other three Doors still lived in either the comfort of their parents’ house (John and Robby) or with their live-in partner out by the Beach (Ray and his future wife Dorothy). There was Jim, and there were The Others. Holzman got this immediately, and decided early on that the key to working successfully with The Doors would be to always keep Jim happy.

Jac painted Jim a picture of the kind of campaign Elektra would build around the album when it was finally released in January 1967: “I said: ‘We’ll have more time to prepare for you and I’ll release no other album that month, which means you’ve got Elektra working a hundred per cent on your album for the first month. And by the way, I have this idea about putting a billboard up on Sunset Strip…’ Well, that caught Jim. He loved that idea. He said: ‘Where’d you come up with that?’”

True to his word, Holzman got his Elektra staff so cranked up on The Doors they could talk of nothing else right through the Christmas holidays, then added the promised cherry of making The Doors the first rock band ever to feature on one of Hollywood’s giant billboards overlooking the Strip.

By then, though, The Doors were starting to feel a sense of entitlement that would soon outgrow a dozen billboards on Sunset Boulevard. A November 1966 residency in New York at the ultra-hip nightclub Ondine’s had seen to that. When Andy Warhol walked with his entourage the first night, he recalled Gerard Malanga – the college dropout-poet-actor-scenester who had appeared in five of Andy’s celebrated ‘art movies’ before he was 22 – freaking out, screaming about Jim: “He stole my look!”

It was true. When Warhol’s Exploding Plastic Inevitable, as it was dubbed, set up at The Trip in Los Angeles, in May ’66, Jim had been so impressed by Malanga’s macho, crotch-bulging, leather-trousered presence, dancing in a Marlon Brando T-shirt, lifting toy barbells and pretending to shoot up with lighted candles, he immediately set about appropriating the look for his own purposes.

By the time The Doors arrived in New York six months later, Morrison’s leather pants and shirt open to the navel look new look were an established part of his act – and an immediate hit with all the women at Doors shows, who were now starting to outnumber the men. With Elektra now pushing The Doors as ‘the American Rolling Stones’, this was a masterly piece of PR equating the recent hit Stones album, Aftermath – a glowering, almost gothic work that had been a turning point for the Stones – with the crazy, head-spinning trip The Doors were about to take you on.

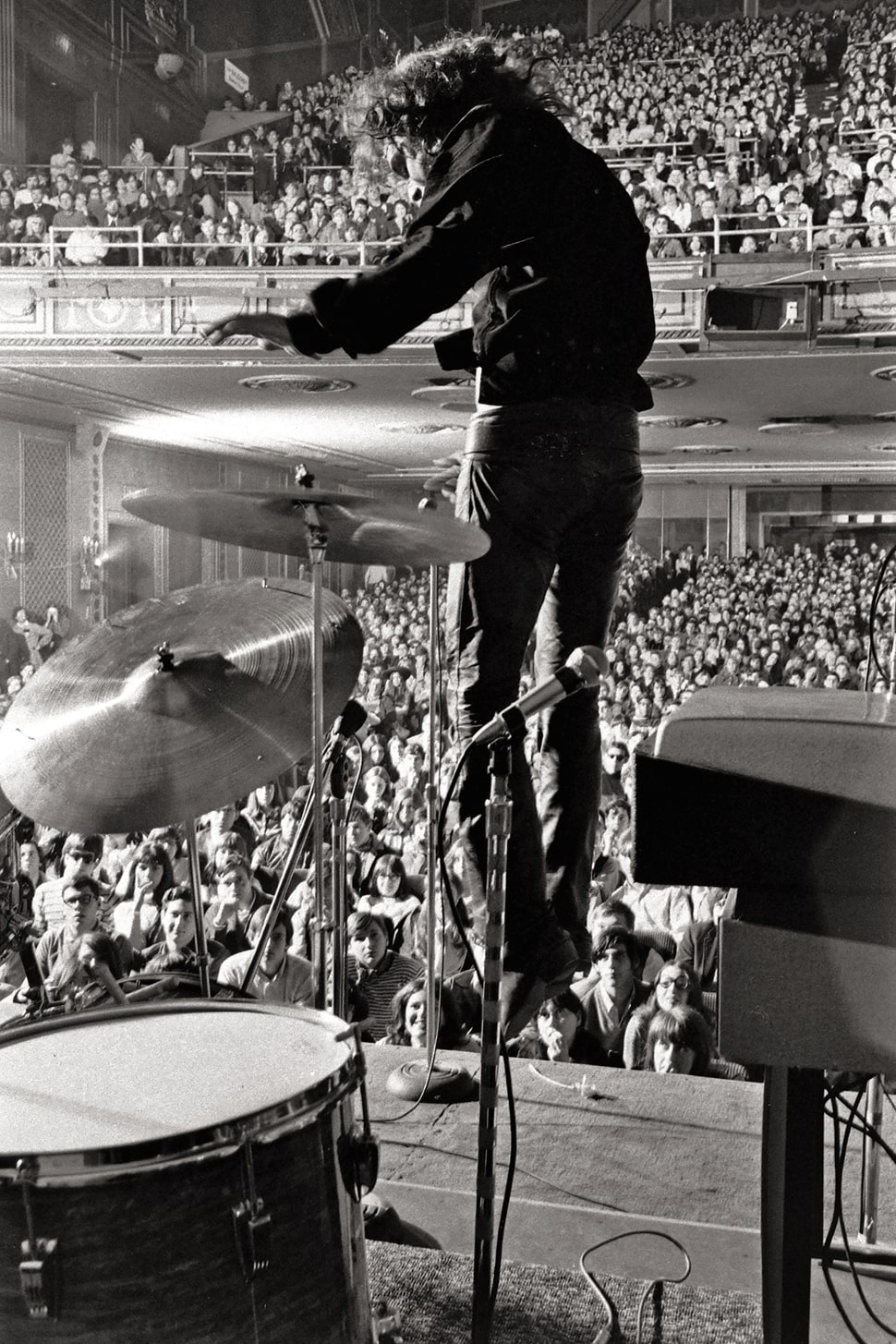

As Ray Manzarek would tell me: “As Jim once said: ‘We perform a musical séance. Not to raise the dead, but to palliate the dead, to ease the pain and the suffering of the dead and the living.’ And in doing that we dove into areas that were deeply, deeply Freudian, and psychologically deeply Jungian at the same time. So we were a merging of both Freud and Jung. Which might seem impossible, but it happened on stage, and really upset the establishment. There was just something about the power in the music, and that insane sexuality of Jim Morrison, that drove the establishment right over the edge.”

One convert was Gloria Stavers, a 39-year-old former model. Then editor of 16 magazine, at the time the biggest-circulation teen mag in America, Stavers had once been Lenny Bruce’s girlfriend, and had helped, through her patronage, turn Herman’s Hermits into bigger stars in America than both The Beatles and the Stones. Gloria liked to photograph the bands herself, inviting them to her New York loft apartment, where if all went well the session would conclude in her bedroom.

When the freelance writer-turned-ad-hoc Elektra publicist Danny Fields arranged for Jim and The Doors to spend an afternoon being shot at Gloria’s apartment, the band were quickly dismissed while she got down to her real work: photographing – then seducing – Jim.

According to Fields, “she was giving [Jim] a blowjob – and she swears he vanished; he dematerialised and was sitting on the other side of the room,” he laughed. However implausible Jim’s dematerialisation mid-blowjob may be, the fact is that when The Doors was released in January 1967, it would be Jim’s image on the cover of 16 that month, under the heading: ‘Morrison is Magic!’

Andy Warhol, meanwhile, was now plotting to get Jim to star in his next movie project, simply called Fuck. He begged Jim to let him film him having sex with Velvet Underground chanteuse Nico. When Jim laughed in his face, Andy wheedled: would he at least allow him to film Nico giving Jim a blowjob? “Fuck off, Andy.”

Jim now seriously considered changing his name to James Phoenix, going so far as to request that Elektra alter his credits on the forthcoming album sleeve. The rest of the band assumed he wanted to sound more like a Warholian rock star, but secretly Jim was more concerned that his growing reputation for debauchery might badly impact on his estranged father’s career in the US military, where he would soon be a Rear Admiral.

When the others talked him out of it – “It just sounded dumb, even for a warrior poet,” explained Ray disingenuously – he settled instead for merely being an orphan. Back in LA for Christmas, when Elektra requested biographical information from the four band members so that they could assemble a press package in readiness for the album’s release in January, Jim claimed his whole family were dead. When asked standard stuff for 1966 like: who are your favourite singers? He replied: “Frank Sinatra and Elvis Presley.”

This was no joke, though. He adored both singers, did everything he could to try to sound like them. When asked for his personal philosophy, however, Jim couldn’t help himself and gave it both barrels: “It’s the feeling of a bowstring being pulled back for twenty-two years and suddenly being let go… I’ve always been attracted to ideas that were about revolt against authority. I am interested in anything about revolt, disorder, chaos – especially activity that seems to have no meaning.”

Elektra, though, had their own ideas about the ‘meaning’ some people might take from Doors songs, and, to the band’s dismay, decided unilaterally to edit the first single from the album, Break On Through (To The Other Side) so that the line ‘She gets high’, which Jim sings four times, on the single version scanned as, ‘She gets… she gets… she gets… she gets…’

This became the version the group were forced to mime to in their first ever television appearance, on Shebang, on January 1, 1967. You can see the frustration in Jim’s wincingly subdued performance, barely bothering to move his lips, eyes wide shut, as he stands there, all gussied up for the cameras in fawn-coloured trousers tapered at the ankles, black shirt and dark hunting jacket, but with an attitude as sullen as a teenage punk-girl forced to wear a pretty dress for the prom.

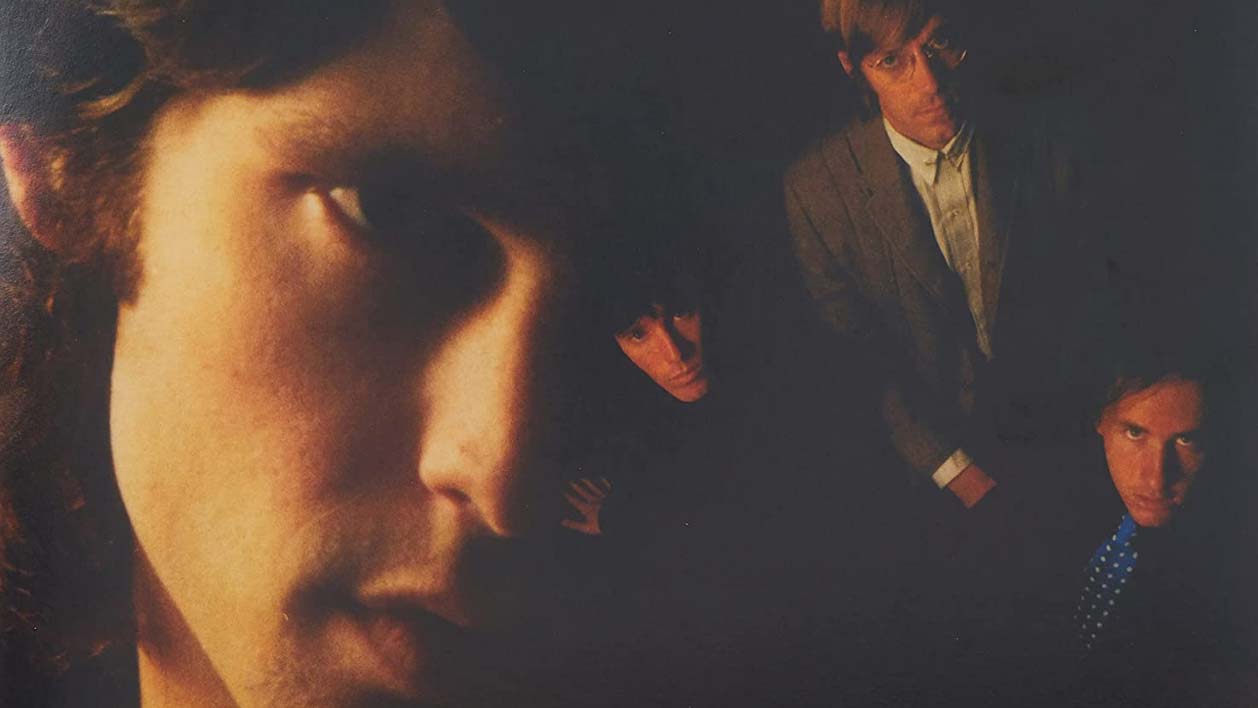

That performance stands in marked contrast to the film clip that Holzman commissioned to shoot: a suitably noir-ish colour clip defined by its stark black tones, no one but a snarling Jim seen for the first minute, and then only the heavily silhouetted form of Ray stooped over his keyboards, the priest at his lectern, Robby not getting a look in until the song is almost over. Yet it was this dark, somnambulant quality – the antithesis of the bright Californian mien of The Byrds, the Beach Boys – that helped define The Doors as different, special. So that when the clip aired on the LA TV show Boss City, it resulted in the band’s first serious plays on local radio.

None of this, though, gave the single the impetus it needed to ‘go national’; that is, give The Doors their first recognisable countrywide hit.

Danny Fields claims it was he who first brought the commercial potential of Light My Fire to the attention of Holzman. “They’d already released another one, but it was Light My Fire that made all the difference, that made the company from a small, classy company into a marketplace force.”

Speaking now, Holzman insists Light My Fire had always been in his thoughts, pointing out that the full seven-minute version from the album was already being played on the new, longer-format stereo FM stations.

“I was counting on FM radio to force AM radio to play it.” The problem was AM had strict rules about ‘needle-time’ – no shorter than two minutes 45 seconds, no longer than three minutes. So Jac asked Paul to cut an edited version that would fit. Paul was sceptical. Jac told him to get on with it. The producer eventually cut out nearly five minutes’ worth of the solos Ray and Robby had spent so long perfecting. The result was the defining hit song of the Summer of Love. And nobody, not even Jac Holzman, could have predicted that.

The band’s only real stipulation, made at Jim’s instigation, was that the band be an equal four-part democracy, with all songwriting credits split equally and credited simply to The Doors, and that all decisions pertaining to their music and business had to be unanimous before they could be acted on. It seemed like the perfect all-for-one strategy to bind them against whatever vicissitudes having a major record company and management behind them might bring; if everything else failed, they would have each other. It was a decision they would all later regret, in one way or another.

Meanwhile, with both Break On Through (To The Other Side) and The Doors now on release, and Sal and Asher working their mojo, the start of 1967 found the band appearing in San Francisco for the first of two weekends at Bill Graham’s famous Fillmore, opening on bills headlined by the Young Rascals the first weekend, the Grateful Dead the second.

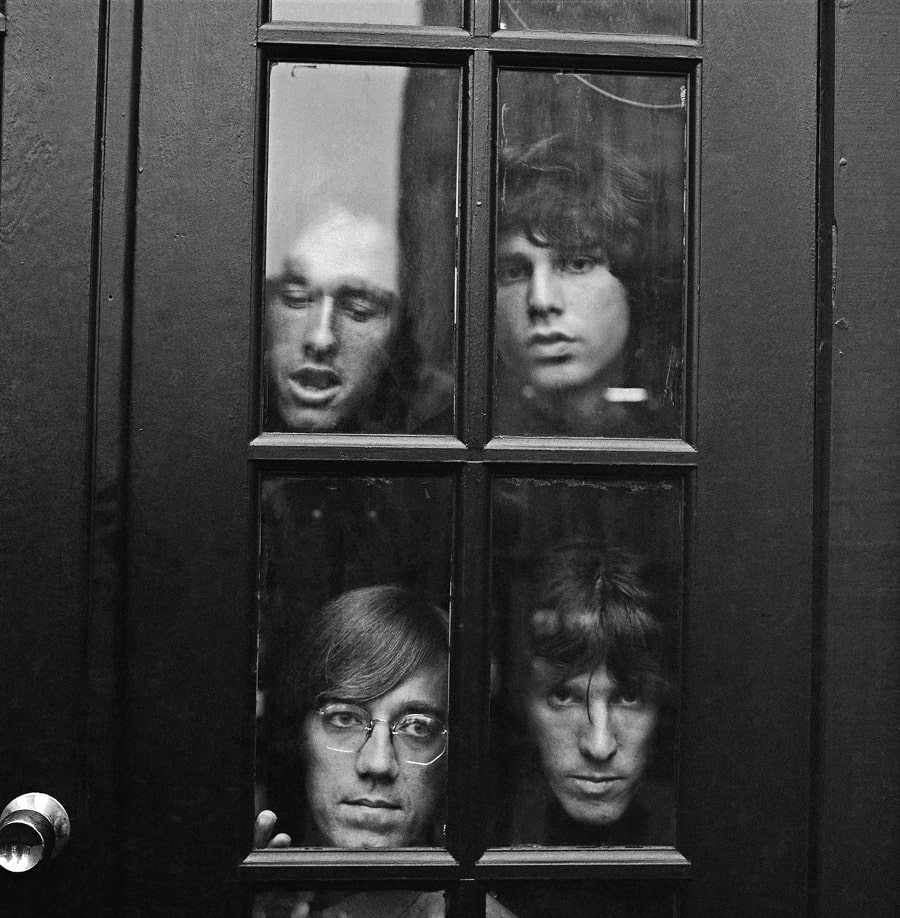

A week later The Doors were back in New York for their second residency at Ondine’s. It was during this trip that the now famous ‘young lion’ shots of Morrison were taken by the distinguished New York photographer Joel Brodsky. He’d already done one session with The Doors on their previous visit to NY, a shot from which adorned the back cover of The Doors: a technically advanced for the time quadruple exposure combining portraits of the individual group members that would later be nominated for a Grammy.

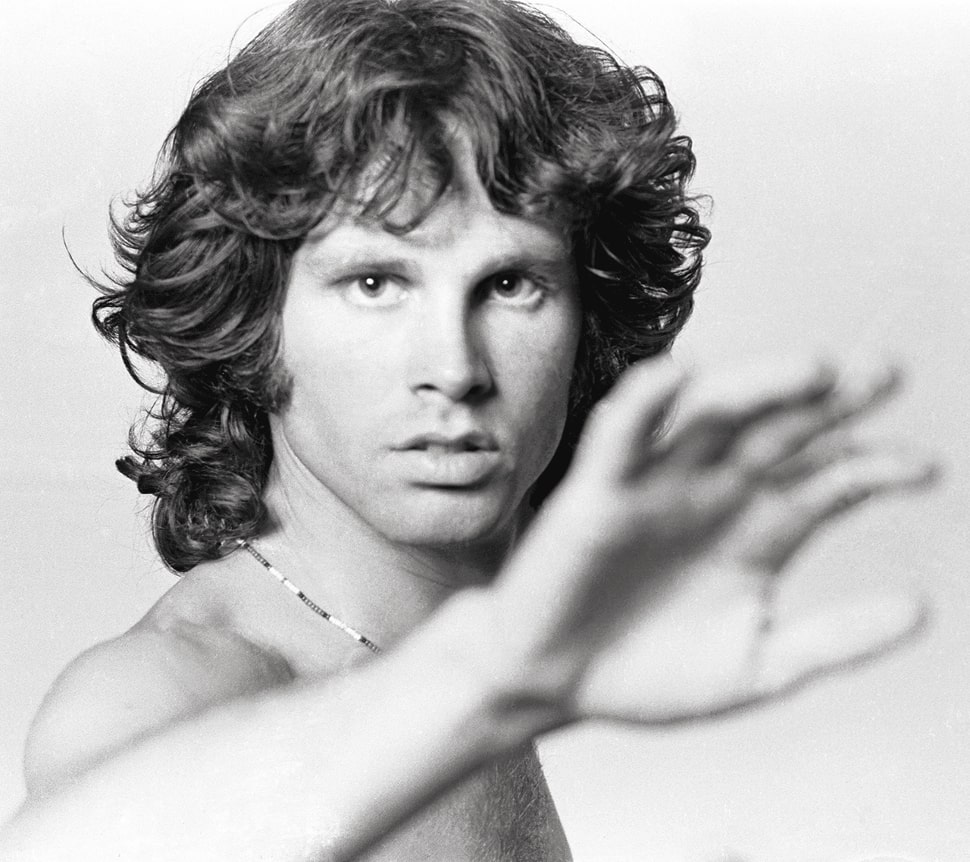

Now, though, he would take the most iconic shots of his – and The Doors’ – career. “I never actually heard him listen to the music he shot,’ said his son-in-law, Sid Holt, a former managing editor of Rolling Stone. “He didn’t particularly like The Doors.”

Maybe so, but it’s Brodsky’s shots – an extended series of black-and-white pictures of a shirtless Jim posing with a string of beads around his muscled neck, his hair a halo of waterfall curls, his face as expressionless as the moon, arms outstretched in mock crucifixion pose, now known as the ‘Young Lion’ shots – that remain to this day the defining image of Jim Morrison, and therefore The Doors.

As usual, Jim had been drinking throughout the day and was ‘pretty loose’ by the time Brodsky began suggesting poses. The ‘American Poet’ shot, as Brodsky called it, was one of the last to be taken. And while the singer’s “equilibrium wasn’t too terrific” he was “great to photograph because he had a very interesting look”.

When, a week later, the Village Voice ran the iconic Christ-like shot of Jim, arms stretched in supplication, in the showpiece article by the staff writer Howard Smith, under the heading ‘New Teen Idol’, Brodsky found himself inundated with “something like ten thousand requests for the picture”. “You know, Morrison never really looked that way again,” he reflected, “and those pictures have become a big part of The Doors’ legend. I think I got him at his peak.”

The Doors was now selling upwards of 10,000 copies a week on the West Coast, even if it was still barely registering anywhere else outside New York.

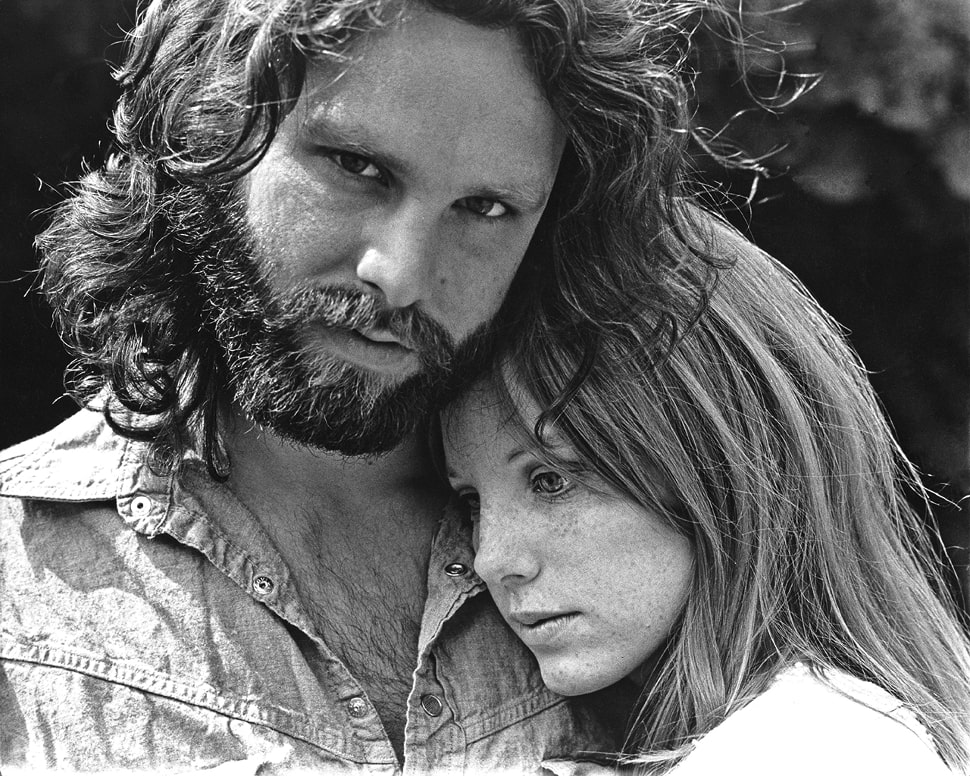

Pamela Courson, who had lately started wearing a ring on her wedding finger and referring to herself as Mrs Morrison, now came to every show she could, increasingly bedevilled by the knowledge that each gig offered her ‘husband’ a thousand opportunities to leave the show with someone else. On this occasion she was accompanied by Tom Baker, a stage actor from New York who had recently worked with Norman Mailer on the short-lived Off-Broadway production of his novel The Deer Park.

Like Jim, Tom was a good-looking, fucked-up boy from a military family whose talent was only matched by his unquenchable thirst for booze, drugs and ‘good times’. The next time The Doors left town, Pam began a very public affair with Baker – payback, perhaps, for Jim’s own barely concealed infidelities. Or just Pam proving that anything Jim could do, she could do better. As future Morrison biographer Jerry Hopkins observed, Pam was Jim’s “mirror image with tits”.

The following month The Doors were back for their third, and final, residency at Ondine’s, three weeks of shows that would see them playing three sets a night, five nights a week. The quality of the shows differed each night, each set, each number sometimes, depending on the condition Jim was in. Livid with rage at Pam’s affair with Tom Baker, it was this energy that helped fuel some of his most intense performances with The Doors.

The band was also reaching a new, dizzying peak, in a hurry to include new works-in-progress into the set such as People Are Strange, a new, more finessed version of Moonlight Drive and, especially, what looked to be a sequel to The End, a whale song of environmental despair called When The Music’s Over. Like its witchy precursor, some nights it would stretch and contort to 10, 15 minutes, sometimes even longer; Jim improvising more poetry over the top, adding new lines, new verses, new worlds each time they performed it, the rafters of the tiny club’s ceiling seeming to enclose his head in a wooden crown, the band hypnotised over their instruments like medieval monks in rapture at their illuminations.

With Elektra getting ready to release the new, AM radio-friendly, edited-down version of Light My Fire as their next single, the band were also expected to make the most of their off-time in New York too: more photo sessions, more interviews than ever before. And of course, for Jim at least, more drink, more drugs and more women. Standing at the bar each night between sets, he’d throw back double shots of vodka and orange while gobbling up every pill, powder and potion the various hangers-on were only too eager to pass his way.

In his black leather suit, his tea-coloured hair falling in angelic ringlets about his, for once, cleanly shaven face, he looked exactly as he did in the recently published Joel Brodsky ‘Young Lion’ shots, nailed to the cross of his own doomed beauty.

But despite The Doors giving some of the most powerful performances of their short career, Jim Morrison’s off-stage life was already going to hell. He may have still looked like an angel from some decadent rock heaven, but inside he was fighting just to keep his head above the dark waters he now found himself in, caught between his own idealised vision of himself as a hedonistic poet and artist, the latest, maybe greatest, guardian of rock’s philosopher’s stone, and the more realistic expectations of a record company, Elektra, who were about to enjoy the biggest record sales success of their existence with Light My Fire, soon to be the biggest hit of the biggest summer in rock. Ever.

Meanwhile, the rest of The Doors could only look on and wonder ‘what if’. As John Densmore ruefully remarked when we spoke in 2012: “You know, self-destruction and creativity don’t have to come in the same package. Picasso lived to be ninety-one. But in Jim they came together so I had to accept it. We all had to. That was the card we were dealt as a band.” Or as Robby Krieger put it: “With Jim, it wasn’t always easy. It was worth it because of the stuff that we got. But it would have been a lot easier if he’d been just a normal genius. You know?”

But no one else wanted Jim to be a “normal genius”. They just wanted what they got: Jim Phoenix, ready to be shot down in flames.

It’s the image – the fire fully lit – that would finally set The Doors on their way on their journey into night, and one that resonates still, half a century later.

Mick Wall’s Love Becomes A Funeral Pyre: A Biography Of The Doors was published in 2014.