Captain Lockheed And The Starfighters: The story of Robert Calvert’s comical concept album

Robert Calvert’s manic imagination was fuelled by bipolar disorder, but it helped him conceive one of the 70’s most outlandish concept albums

From its first flight on March 4, 1954 it was clear that the Lockheed F-104 was no regular airplane. Distinctively sleek and seemingly dipped in silver, it was the visual personification of the jet age – a time when speed and altitude records were front-page news and outcome of the Cold War seemed inextricably linked to our mastery of the heavens.

Imaginatively nicknamed the Starfighter, its elegantly streamlined design masked a massive single engine. The plane had a cruising speed of Mach 2 – twice the speed of sound - and was capable of rocketing to an altitude of 100,000 feet under its own power.

There had been nothing like it before, and it wouldn’t be long before the dart-shaped marvel was imprinted on the imaginations of pilots and enthusiasts alike – sadly, for all the wrong reasons. The disproportionate fatality rate of the people who flew it ensured the Starfighter would never shake its reputation as a pilot killer, and within a decade a generation of the newly resurrected West German Luftwaffe would rechristen it ‘der Witwenmacher’.

The Widowmaker.

Robert Calvert always dreamed of climbing into the cockpit. A native South African whose family moved to the coastal town of Margate when he was an infant, the man who would one day stand behind the mic for Hawkwind was a true child of the jet age whose childhood fascination with airplanes and their operators would be fuelled by what he’d spy through the chain-link fence at a nearby US Air Force base at Manston.

The stream of fighters and bombers and their crews taking off and landing would leave a deep imprint on the young Calvert’s mind. In his teens, he would join the Air Training Corps, where he reached the rank of corporal and played trumpet for the 438th Squadron band. But his dream of becoming a fighter pilot was crushed by an inner ear defect. It was a disappointment that Calvert would never shake.

“Flying was an obsession with him,” says Nik Turner, Calvert’s sax-toting future bandmate in Hawkwind. “He wanted to be a poet, really, but he also had these obsessions, and that was one of them. I remember knocking around with him, it was maybe 1966, and we’d go boogie to Born To Be Wild and get stoned and have a great time. He’d go and do these poetry readings down in Thanet and Margate, these happenings.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

"I was working on the seafront at the time selling naughty postcards, ‘Kiss Me Quick’ hats and holding drugs for mods. They’d throw a dustbin through a window, grab what they could and then I’d look after them for them. Robert’s mother was a state-registered nurse and she had a cupboard full of drugs, so he and his brother used to steal them and sell them to the mods on the seafront.”

It soon became clear to Turner that there was something profoundly different about his friend, and it wasn’t just his eclectic interests. Calvert suffered from bipolar disorder at a time when the condition was poorly understood by the medical profession and the public at large. His erratic behaviour veered towards the manic.

“My mother was frightened of him,” says Turner. “He used to come by my house and blabber on… people were scared but I never was. He’d always have breakdowns; he’d have one every 18 months according to his mother. He was a very nice guy and very stimulating company, and he turned me on to a lot of very interesting things, like William Burroughs and JP Donleavy, all these weird books, but he had some real difficulties.

"I remember one time he put on his full army uniform with boots and a bloomin’ great big pack and went on a march up the motorway. He put himself in hospital that time. He had an obsession with military things, but he always wanted to fly. I think his dad wanted him to be a real man. He was a foreman on a building site, and I think Robert was always a disappointment to his dad. Psychologically he wanted to impress him, which is where the military thing came from.”

It wouldn’t be long before Turner would decamp to the bright, psychedelic lights of Notting Hill in West London. Calvert would soon follow, getting a job in a tyre shop but rapidly insinuating himself into the fuzzy, anarchic communalism of Portobello Road. Turner was recruited by his friend Dave Brock to haul equipment for his newly formed band Hawkwind Zoo, and would soon join the band outright. Once again Calvert would not be far behind.

During its time in service of the German Luftwaffe, the German version of the F-104, the F-104G, suffered a staggering 29 per cent crash rate which would result in the deaths of 108 pilots. For a nation in peacetime it was a staggering figure, and in the annals of military history it’s a chapter that would generally come to be known as the Starfighter Crisis. The frequency of incidents would soon become the subject of bitter ridicule in the press. The running joke was that best way to own a jet was to simply buy a plot of land. It wasn’t far off.

Theories about the cause abounded – was there something wrong with the plane, or was it the pilots themselves? After all, between 1944 and 1955 the West German military had been grounded during an intense period of evolution in aviation technology that would leave a disastrous knowledge gap in ground maintenance crews and aviators alike. Or maybe there was an inherent danger in using a jet fighter designed for high-speed, high-altitude performance for low-level, low-velocity missions in cloudy circumstances?

Whatever the explanation for the tragic chain of events that would mar the resurrection of the Luftwaffe, something was clearly, devastatingly wrong, and all signs pointed to the F-104G. Arguing that the deployment of planes he felt were unsafe, Erich Hartmann, aka ‘The Black Devil’ and one of the Luftwaffe’s most decorated pilots of all time, would resign his post in protest.

The cultural maelstrom of the Notting Hill and Ladbroke Grove scene was a world away from sleepy Kent, and there Calvert flourished. Hawkwind’s Dave Brock likens its bohemian-carnival atmosphere to San Franciso’s Haight Ashbury a few years earlier. It was a hotbed of musical inspiration and counter-cultural dissent, and an easy place for someone of Calvert’s predilections to blend in.

“It was tribal,” says Brock. “There was a lot of marijuana. We’d play under the flyover on Portobello Road and there’d be these poetry readings with weird electronic music going on – it was just down the road from [counter-cultural publication] Frendz, who Bob was writing for. We’d sit in the newspaper rooms with some grass and discuss the politics of the day. That was a big deal for Bob.”

Hawkwind were full-throttle by the time Robert Calvert began pencilling in the notes for a satirical stage play about doomed fighter pilots. 1971’s iconic In Search Of Space had already hit No. 18 on the UK charts and the single Silver Machine had reached No.3, paving the way for the double-live, performance-art extravaganza that was Space Ritual, another Top 10 album in 1973.

But it was the release of the single Urban Guerilla that same year that gave the band and Calvert a taste of notoriety. The song alluded to the so-called Stoke Newington 8, alleged bomb-makers and members of revolutionary activist group the Angry Brigade for whom Hawkwind had played a benefit gig, and it also chimed with an IRA bombing campaign targeting London. The single would be withdrawn by the band’s management after just three weeks, though not before it was banned by the BBC. Calvert’s flat on Gloucester Road in West London would also be raided on the back of the controversy. Despite it all, he never stopped working.

“His energy would drive you to distraction and make people have breakdowns,” says Hawkwind co-founder and leader Dave Brock. “He’d write a poem, turn around, then write another poem – it was like a runaway train and that intensity affects you. You’d suddenly start becoming hyperactive yourself. The unfortunate thing is guys who do have this genius are often a bit nutty.”

Life in Hawkwind – particularly their heavy touring schedule – did nothing to help Calvert’s mental instability, and he left the band in November 1973. But he didn’t slow down, and he began converting his stage play into a performance-art comedy concept record based around a subject that fascinated him: the Lockheed Starfighter.

“I’ve grown up with the Starfighters, which have accounted for the lives of many young pilots,” said Calvert in a 1973 Melody Maker interview. “It has become so much a part of me that I’ve had to write about it to get it out of my system. The story is a true one. It’s a comical tragedy – a good way to put across a heavy idea. Unfortunately my lifestyle is governed by being a manic-depressive. I started Captain Lockheed by sitting on the old hulk of a boat lying in a cove in Cornwall. It looked like the remains of a crashed aircraft and being near it helped me relate to what I was trying to do.”

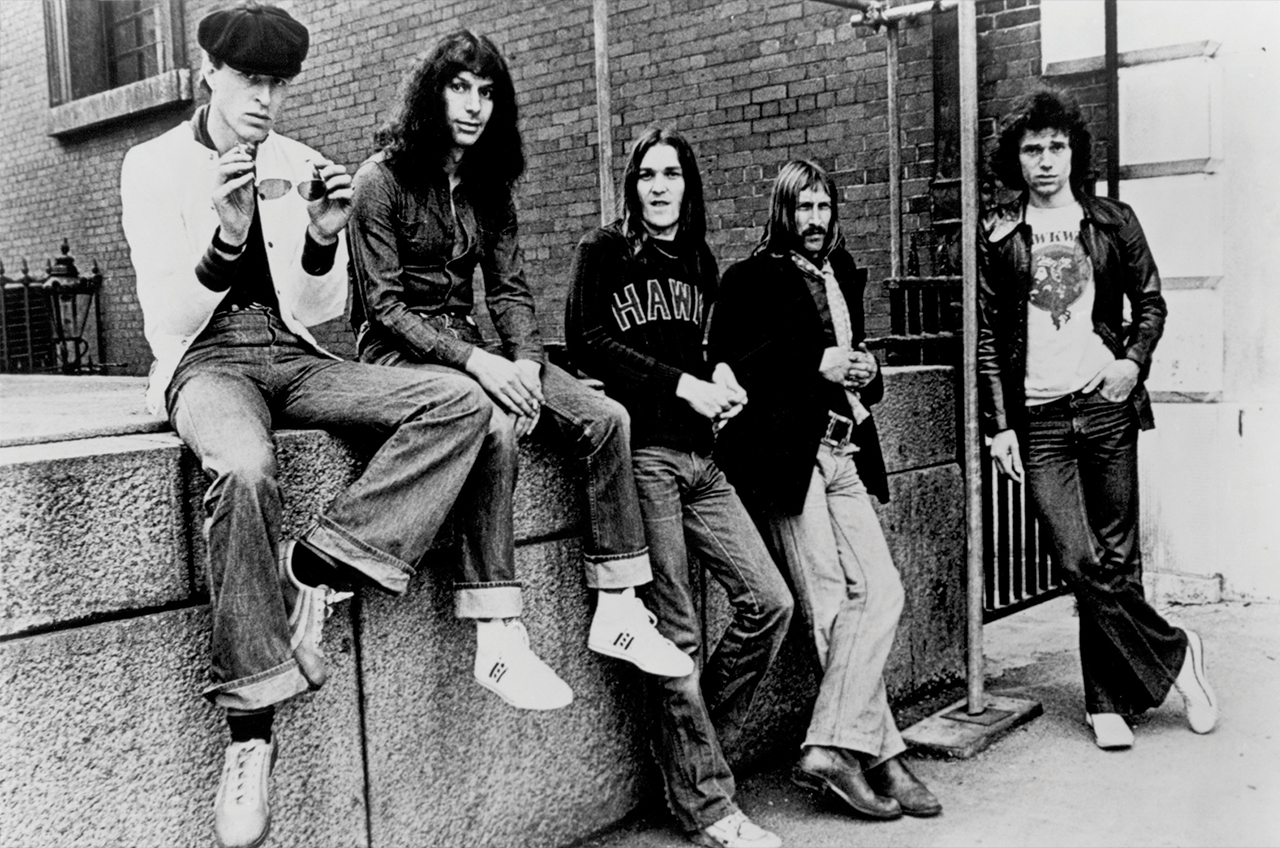

Calvert entered the studio in the spring of 1973 to start working on the album, a process that would take more than 12 months to complete. The cast list of musicians read like a Who’s Who of the British musical underground, including members of Hawkwind and fellow Ladbroke Grove denizens the Pink Fairies, Arthur Brown and Roxy Music man Brian Eno. Piss-taking narration was provided by Traffic drummer Jim Capaldi and the Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band’s charismatic frontman Vivian Stanshall.

“It was quite complex,” says Brock. “All these characters used to hang around Notting Hill Gate except for Arthur. Some of the vocals that were done were basically done as Hawkwind, the band themselves did the backing tracks with all these artists who were brought in. It was some little studio in Notting Hill Gate. Bob and Viv would go into this pub called Finch’s down Portobello Road. They’d take downers and Mandrakes and drink wine. The house itself was a strange place.

"The Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band, they had loads of props and dummies and musical instruments and weird sorts of things with wires sticking out… they’d do weird electronic music. Bob was a great eccentric so you can imagine what that experience was like. I played guitar on loads of tracks, but I’d had a big row with Bob and he never put my name down. I even did backing vocals.

"The only thing he credited me with was The Widowmaker, which was quite strange. He did kind of go up and down and he was a great strain to be with, because all the time you’re trying to give him support and he’d drain you. We all knew he was a bit nutty. It was just one of those things that we had to put up with.”

The resulting album wasn’t just a prog-infused space rock odyssey. It was a gleeful Monty Python meets Catch 22 middle-finger to the powers that be that took the concept of The Right Stuff – the aviation term for that million-dollar cocktail of foolhardy courage and icy reserve so gloriously addressed in Tom Woolf’s 1979 book of the same name – and dropped it on its head.

Time magazine called it the Deal Of The Century in a 1975 article that would send shockwaves around the globe. Within 12 months a United States Senate investigation would reveal in excruciating detail how American aerospace goliath Lockheed had bribed high-ranking foreign officials into authorising the large scale purchase of their F-104 Starfighter, including 900 F-104Gs to Germany.

It was a brutal blow to a German national psyche still traumatised by the events of World War II three decades later. The aerospace industry – that ever-flowing fount of national pride which kept the Cold War arctic and carried citizens through the sound barrier and into orbit and beyond on the wings of Mercury and Apollo – was, it turns out, dirty as hell. The American public, already brutalised by the madness of Vietnam and the red-handed betrayal of Watergate, looked on in resigned disenchantment as more shady deals were uncovered in Japan, Italy, and the Netherlands.

When Captain Lockheed And The Starfighters was released in 1974 it’s easy to imagine that there would be little there to startle Hawkwind fans who had been there from the beginning, but at that time there was simply nothing else like it. Not only had it anticipated a political meltdown by 12 months, it’d kicked the shit out of it, laughing all the way.

“I think people got what Bob was doing,” says Turner, “I think some of the more inspired people got it, that is. It wasn’t generally accepted, but it could have been a hit record – there were a lot of tracks on it that are crucial to the genre, like Ejection, or The Right Stuff.”

Despite a lukewarm reception to this uniquely satirical, am-dram proto-punk masterpiece, there were younger ears to whom Calvert’s vision would inspire.

“Screaming fucking Germans and fighter planes!” says Monster Magnet frontman and Calvert devotee Dave Wyndorf, who paid tribute to his spiritual forefather by covering Lockheed track The Right Stuff on his own band’s 2004 album, Monolithic Baby!. “My god, those things were just not a part of 1974. It was just not a politically correct thing. I already owned every other Hawkwind record but I had no idea it’d be that insane.

"For me, this kid who grew up in New Jersey watching The Great Escape and reading comic books, it just blew everything else away. It was hysterical. I can’t even imagine Hawkwind fans of the time understanding what was going on. It’s some pretty sophisticated material coming out of that drug rock vibe. All the punk rock guys know it…”

Indeed, it would be a mistake to dismiss Lockheed as a mere comedy record or Hawkwind offshoot. Deeply cynical but never severing itself from the very real tragedy and criminality of the events that inspired it, it would serve as part of the blueprint for an up-and-coming generation of disenfranchised rock fans who would fuse the simple, monumental three-chord bombast of The MC5 with politically informed, verbally irate discourse. One of those fans was Jello Biafra of San Francisco punk icons The Dead Kennedys.

“There would be no Holiday In Cambodia if there was no Hawkwind,” Biafra tells Classic Rock. “As a kid, I’d read a preliminary overview of space rock in one of my dad’s issues of Penthouse magazine, and I found Space Ritual by Hawkwind and it blew me through the wall.

"Lockheed was only available on import in America, and this was in the time before punk so people who liked music and liked to try new things didn’t have many places to go, so there was a somewhat booming business being done in some areas. I was already a massive Hawkwind fan, so I got a hold of Lockheed and I was blown away by this pile-driving hypno-rock. It was probably even more primal than what Hawkwind was doing.

“And who could argue with the concept? At the time, that level of bribery and corruption wasn’t new to the average American, let alone the average American teenager who was already reeling from Watergate and Vietnam and CIA spying scandals all coming out at once. It only occurred to me later: ‘Hey, wait a minute, this album was released one or two years before Lockheed’s scandal even broke in the media. How does an artist from the so-called space rock world even find out about this stuff?’”

On February 13, 1976, Lockheed chairman Daniel Haughton and vice chairman Carl Kotchian would resign from their posts in the wake of one of the biggest political scandals since Nixon. New president Jimmy Carter would sign the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act. It was an appropriate gesture – Lockheed executives had been found to have paid millions in bribes for over ten years to key decision makers in places as far afield as Japan, West Germany, Saudi Arabia, Hong Kong, and perhaps most sensationally Prince Bernhard, husband of Holland’s Queen Juliana.

For the families and loved ones of the pilots who’d lost their lives, it was scant consolation, and would forever tarnish the legacy of an engineering feat once destined for greater things.

For the musicians behind Captain Lockheed And The Starfighters, there was no satisfaction when the scandal finally broke. “We were just sad about those fucking pilots who climbed into those planes,” says Dave Brock.

As for Robert Calvert, it would mark a creative high-point, though he would continue his solo work, most with Lucky Leif And The Longships, a concept record speculating on present-day America had the Vikings succeeded in colonising it. He eventually moved to Devon, into a converted cottage owned by Brock, rejoining him for a tour with Hawklords after a legal dispute with Hawkwind management dispute briefly forced Brock to change his band’s name. He’d continue writing plays and performing poetry.

“I had a farm and we’d go backwards and forwards to each other’s places,” Brock says. “He never changed. There was this woman he was obsessed with and wanted to get married to. He saw an ad in the paper for a Vauxhall Velox, and Bob decided he was going to buy it for her. He went and found the guy who’d just sold it and Bob just went bananas. He wanted my shotgun – he’d just have these total freakouts. There were so many wonderful moments and terrible mayhem with him.”

Work would eventually begin on Earth Ritual, an sequel to Space Ritual, mooted to be about a journey into the Earth. An EP titled The Earth Ritual Preview was released in 1984, but the full album was never completed. Robert Calvert died of a heart attack in 1988. He was 43.

“He had this wonderful idea about making a whole show based on Earth Ritual,” says Brock. “We were really excited about it. I remember I was out playing a free festival, having my dinner, and somebody came by and told me the bad news. It was like: ‘Oh Christ.’”

“We always remained friends,” adds Turner. “He was just this force, a creative spirit who needed help sometimes. I was so saddened when he died, I wish I’d been there with him.”

This feature was originally published in Classic Rock 222, in March 2016.

Alexander Milas is an erstwhile archaeologist, broadcaster, music journalist and award-winning decade-long ex-editor-in-chief of Metal Hammer magazine. In 2017 he founded Twin V, a creative solutions and production company. In 2019 he launched the World Metal Congress, a celebration of heavy metal’s global impact and an exploration of the issues affecting its community. His other projects include Space Rocks, a festival space exploration in partnership with the European Space Agency and the Heavy Metal Truants, a charity cycle ride which has raised over a million pounds for four children's charities which he co-founded with Iron Maiden manager Rod Smallwood. He is Eddietor of the official Iron Maiden Fan Club, head of the Heavy Metal Cycling Club, and works closely with Earth Percent, a climate action group. He has a cat named Angus.